Bridging The Gap Between Law And Society

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.CHAPTERONEBridging the Gap between Law and SocietyLAW AND SOCIETYThe law regulates relationships between people. It reflects the val ues of society. The role of the judge is to understand the purposeof law in society and to help the law achieve its purpose. But thelaw of a society is a living organism.1 It is based on a factual andsocial reality that is constantly changing.2 Sometimes the change isdrastic and easily identifiable. Sometimes the change is minor andgradual, and cannot be noticed without the proper distance andperspective. Law’s connection to this fluid reality implies that it toois always changing. Sometimes a change in the law precedes socie tal change and is even intended to stimulate it. In most cases, how ever, a change in the law is the result of a change in social reality.Indeed, when social reality changes, the law must change too. Justas change in social reality is the law of life,3 responsiveness tochange in social reality is the life of the law.These changes in the law, caused by changes in society, are some times appropriate and sufficient. The legal norm is flexible enough toreflect the change in reality naturally, without the need to change thenorm and without creating a rift between law and reality. For exam ple, the legal prohibition against possessing weapons works well,without the need for change, whether the weapon is an antique pistol1See Brian Dickson, “A Life in the Law: The Process of Judging,” 63 Sask. L. Rev.373, 388 (2000).2See Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Paradoxes of Legal Science 10–11 (GreenwoodPress 1970) (1928).3See William H. Rehnquist, “The Changing Role of the Supreme Court,” 14 Fla.St. U. L. Rev., 1.For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.4CHAPTER ONEor a sophisticated missile. Often, however, the legal norm is not flex ible enough, and it fails to adapt to the new reality. A gap has formedbetween law and society. We need a new norm. For example, thenorm that the owner of a carriage owes a duty of care to a pedestrianmay be flexible enough to solve the problem of the duty of care thatan automobile owner owes to a pedestrian. However, it is not flexi ble enough to solve the problem of industrialization, urbanization,and thousands of cars traveling on the streets, a situation in whichproving negligence becomes more and more difficult. We need achange in law to move from negligence-based liability to strict liabil ity in the context of an insurance regime. When changes occur insocial reality, many of the old legal norms fail to adapt. The tort ofnegligence, which can generally deal with various changes in con ventional risks, will likely prove insufficient to address an atomic risk.We would need a formal change in the norm itself.The life of law is not just logic or experience.4 The life of law isrenewal based on experience and logic, which adapt law to the newsocial reality. Indeed, there are always changes in law, caused bychanges in society. The history of law is also the history of adapting lawto life’s changing needs. The legislative branch bears the primary rolein making conscious changes in the law. It has the power to change thelegislation that it itself created. It has the power to create new legaltools that can encompass the new social reality and even determine itsnature and character. In the field of legislation, the legislature is thesenior partner. The role of the judge is secondary and limited.CHANGES IN LEGISLATIONAND IN ITS INTERPRETATIONThe judge has an important role in the legislative project: The judgeinterprets statutes. Statutes cannot be applied unless they are inter preted. The judge may give a statute a new meaning, a dynamicFor a different view, see Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Common Law 1 (1881):“The life of law has not been logic: it has been experience.”4For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.T H E G A P B E T W E E N L AW A N D S O C I E T Y5meaning, that seeks to bridge the gap between law and life’s chang ing reality without changing the statute itself. The statute remainsas it was, but its meaning changes, because the court has given it anew meaning that suits new social needs. The court fulfills its roleas the junior partner in the legislative project. It realizes the judicialrole by bridging the gap between law and life. I noted as much in acase that addressed, among other things, the question of whetherIsrael’s civil procedure regulations recognized a class action lawsuitagainst the state. In answering in the affirmative, I noted:We are concerned with the existing law, which must be given a newmeaning. This is the classic role of the court. In doing so, it realizesone of its primary roles in a democracy, bridging the gap between lawand life. The case before us is a simple example of the many situationsin which an old tool does not fit a new reality, and the tool thereforemust be given a new meaning, in order to address society’s changingneeds. It is no different from the many other situations in whichcourts today are prepared to give a dynamic meaning to old provi sions, in order to adapt them to new needs.5Here is an additional example: Israeli tort law is based on theTort Ordinance, passed at the end of the period of the BritishMandate in Palestine (1947). According to the Ordinance, if an actof negligence causes a person’s death, his dependents are entitledto compensation from the tortfeasor. The Tort Ordinance definesdependents to include “husband, wife, parents, and children.” Thisprovision was taken from the English statute, passed in 1846.There is no doubt that the British mandatory legislature intendedto refer to a husband and wife who were lawfully married.However, what of the common law wife who has lived with hercommon law husband for many years and even given birth to adaughter with him? The common law husband becomes the victimof a deadly work-related accident; is the common law wife entitledto damages from the tortfeasor for loss of her dependency? WhenL.C.A 3126/00, State of Israel v. A.S.T. Project Management and Manpower,Ltd., 47(3) P.D. 241, 286.5For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.6CHAPTER ONEthe question came before the Israeli Supreme Court, at a timewhen the phenomenon of common law marriages was prevalent,the Court answered in the affirmative. In my opinion, I wrote:I am prepared to assume that the phrase “wife” in the 1846 Englishstatute refers to a married woman. However, that does not mean thatit is the meaning that an English court would give it today. It cer tainly does not mean that it is the meaning that we, in the State ofIsrael, would give the phrase “Husband, Wife.” Much water hasflowed through the English Thames and the Israeli Jordan since1846. As judges in Israel, our duty is to give the phrase “Husband,Wife” the meaning assigned to it in Israeli society, and not in EnglishVictorian society of the mid-nineteenth century . . . that is mandatedby our interpretive rules.6Here is an additional example from public law: The DefenseRegulations (State of Emergency) enacted in 1945 by the Britishgovernment continue to apply in Israel. Among other things, theseregulations establish military censorship of publications in Israel. Themilitary censor is authorized to ban publications that it deems likelyto harm state security, public security, or the public peace. TheSupreme Court has given this provision a dynamic interpretation,based on the fundamental principles of Israeli law. In my opinion, Inoted thatThe meaning that should be given to the Defense Regulations in theState of Israel is not identical to the meaning that they might havetaken on during the period of the Mandate. Today, the DefenseRegulations are part of the laws of a democratic state. They must beinterpreted against the background of the fundamental principles ofthe Israeli legal system.7We held that the military censor may prevent publication only if theuncensored publication would create a near certainty of grave harmto state security, public security, or public peace.C.A. 2000/97, Lindoran v. Kranit–Accident Victim Compensation Fund, 55(1)P.D. 12.7H.C. 680/88, Schnitzer v. Chief Military Censor, 42(4) P.D. 617, 628.6For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.T H E G A P B E T W E E N L AW A N D S O C I E T Y7Characteristic of these examples and many others is the changethat has taken place in the law without any change occurring in thelanguage of the legislation. Such a change is made possible bythe change in the court’s interpretation. It is made possible by thecourt’s recognition of its role to bridge the gap created betweenthe old statute and the new social reality. The court did not say,“Adapting the law to the new reality is not my role. It is the roleof the legislature. If the legislature does not do anything, it bearsthe responsibility.” The court viewed it as its own responsibility—complementary to the responsibility of the legislature—to give theold law a new meaning that suited the social needs of modern Israel.Statutory interpretation will facilitate the statute’s adaptation tochanges in the conditions of existence only if the system of inter pretation allows for that. Such a system is the system of purposiveinterpretation.8 It is predicated on giving a dynamic interpretationto the statute, to allow it to fulfill its design. In one case, Iaddressed the way in which dynamic interpretation works:The meaning that should be given to a phrase in a statute is not fixedfor eternity. The statute is part of life, and life changes. Understandingof the statute changes with changes in reality. The language of thestatute remains as it was, but the meaning changes along with “chang ing life conditions” . . . the statute integrates into the new reality. Thisis how an old statute speaks to the modern person. This is the sourceof the interpretive approach that “the statute always speaks” . . . inter pretation is a regenerative process. Old language should be filled withmodern content, in order to minimize the gap between law and life.It is therefore correct to say, as Radbruch does, that the interpretermay understand the statute better than the author of the statute, andthat the statute is always wiser than its creator . . . the statute is a livingcreature; its interpretation must be dynamic. It must be understood ina way that integrates and advances modern reality.9Infra p. 125.C.A. 2000/97, supra p. 6, note 6 at 32. The reference is to Gustav Radbruch,“Legal Philosophy,” in The Legal Philosophies of Lask, Radbruch, and Dabin 141(20th Century Legal Philosophy Series, Vol. IV, Kurt Wilk trans., 1950).89For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.8CHAPTER ONEOf course, it is not always possible to bridge the gap between lawand life by giving a new and modern meaning to an old statute.Sometimes the judge lacks the power to bridge the gap betweenthe old language of the statute and society’s new reality. In such acase the judge must set aside his work tools. The judge may not actagainst the law. He can only hope that the legislature will do its joband repeal the old statute. The judge, as a faithful interpreter, can not achieve such a result. For example, the court could not entirelyrepeal the military censorship of publications or, for that matter,civilian censorship of plays and movies, also created by the Britishmandatory regime. Such repeal required legislative intervention.Indeed, following a decision by the Supreme Court restrictingcivilian censorship, the legislature repealed censorship of plays.Censorship of movies, like military censorship, still exists. Thejudge lacks the power to deliver that change.In this context, Guido Calabresi’s proposition10 is noteworthy.He suggested that courts should be able to repeal legislation thathas become obsolete. Of course, Calabresi’s proposition cannot beimplemented unless the legislature explicitly authorizes courts torepeal obsolete legislation. I personally do not think that is theproper solution to a painful problem. The right way is not to relyon judges to repeal obsolete laws but rather for the legislature todo so. Indeed, the Israeli legislature occasionally collects pieces ofold legislation that are no longer necessary and repeals them. Thatis the right way to proceed.CHANGES IN SOCIETY AFFECTINGTHE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF STATUTESSocial changes sometimes lead to a situation in which a statutepassed in the context of a certain reality and that was constitutionalat the time of its enactment becomes unconstitutional in light of a10Guido Calabresi, A Common Law for the Age of Statutes (1982).For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.T H E G A P B E T W E E N L AW A N D S O C I E T Y9new social reality. Of course, the court will do everything it can togive the old statute a new meaning, in order to preserve its con stitutionality. The limitations of interpretation, however, do notalways allow that to happen. Where interpretation fails to give anold law a new meaning, the question may arise as to whether, inlight of the social changes, the old statute is constitutional. Eventhough the court is not authorized to give a new meaning to an oldstatute, if such meaning deviates from the system’s rules of inter pretation, the court may declare the old statute, with the old mean ing, unconstitutional. As an example, in 1986 the United StatesSupreme Court held that a statute criminalizing consensual homo sexual relations between adults was constitutional.11 Twenty yearspassed. The United States Supreme Court overturned its priorholding.12 It held that the Constitution bars legislation criminal izing consensual sexual relations between adults. The differencebetween the two decisions did not reflect a constitutional changethat took place during that period. Rather, the change thatoccurred was in American society, which learned to recognize thenature of homosexual relationships and was prepared to treat themwith tolerance.13 Justice D. Dorner of the Israeli Supreme Courtdiscussed this social change in a case that raised the issue ofemployee benefits for same-sex partners:In the past, intimate relations between members of the same sex—relations considered to be a sin by monotheistic religions—were acriminal offense . . . this treatment has gradually changed. Legalscholars have criticized the definition of a homosexual relationship ascriminal and discrimination against homosexuals in all areas of life . . .movements fighting for equal rights for homosexuals have sprungup. Today, the trend—which began in the 1970s—is to a liberalBowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986).Lawrence v. Texas, 123 S. Ct. 2472 (2003).13Robert Post, “Foreword: Fashioning the Legal Constitution: Culture, Courts,and Law,” 117 Harv. L. Rev. 4 (2003).1112For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.10CHAPTER ONEtreatment of a person’s sexual tendencies, which are viewed as aprivate matter. . . . Israeli law concerning homosexuals reflects thesocial changes that have taken place over the years.14CHANGES IN THE COMMON LAWThe court may not repeal an obsolete statute. It may, however,repeal a common law holding that has become obsolete. It maychange even a non-obsolete precedent if it does not suit today’ssocial needs. Indeed, judges created the common law. In doing so,they sought to provide a solution to the social needs of their time.As these needs change, judges must consider whether it is appro priate to change the judicial precedent itself, by expanding orrestricting the existing case law or overturning an old precedent.15Sometimes the new social reality necessitates creating new case lawto resolve problems that did not arise at all in the past, where thegoal of the new case law is to bridge the gap between law and thenew social reality. Justice Agranat expressed this idea well:Where a judge is presented with a set of facts based in new life condi tions, for which the current law was not designed, the judge shouldreview anew the logical premise on which the case law, created in a dif ferent background, is based. The goal is to adapt the case law to thenew conditions, either by expanding or restricting it, or, where thereis no other way, completely to abandon the logical premise whichserved as the basis for the existing law and to replace it with a differ ent legal norm—even if the legal norm was previously unknown.16Within the common law project, the judge is the senior partner.The judge creates the common law and bears responsibility formaking sure that it fulfills its role properly. The legislature is theH.C. 721/94, El Al Israeli Airlines v. Danielovitz, 45(5) P.D. 749, 779(English translation available at www.court.gov.il).15See infra p. 158.16C.A. 150/50, Kaufman v. Margines, 6 P.D. 1005, 1034.14For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may bedistributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanicalmeans without prior written permission of the publisher.T H E G A P B E T W E E N L AW A N D S O C I E T Y11junior partner, the outside observer, who generally intervenes onlywhen asked to correct a particular issue or replace the entire legalregime from a common law regime to a statutory regime.CHANGE AND STABILITYThe Dilemma of ChangeThe need for change presents the judge with a difficult dilemma,because change sometimes harms security, certainty, and stability.The judge must balance the need for change with the need for sta bility. Professor Roscoe Pound expressed this well more than eightyyears ago: “Hence all thinking about law has struggled to reconcilethe conflicting demands of the need of stability and of the need ofchange. Law must be stable and yet it cannot stand still.”17Stability without change is degeneration. Change without stabilityis anarchy. The role of a judge is to help bridge the gap between theneeds of society and the law without allowing the legal system todegenerate or collapse into anarchy. The judge must ensure stabilitywith change, and change with stability. Like the eagle in the sky, whichmaintains its stability only when it is moving, so too is the law stableonly when it is moving. Achieving this goal is very difficult. The lifeof the law is complex. It is not mere logic. It is not mere experience.It is both logic and experience together. The

Bridging the Gap between Law and Society LAW AND SOCIETY The law regulates relationships between people. It reflects the val ues of society. The role of the judge is to understand the purpose of law in society and to help the law achieve its purpose. But the law of a so

May 02, 2018 · D. Program Evaluation ͟The organization has provided a description of the framework for how each program will be evaluated. The framework should include all the elements below: ͟The evaluation methods are cost-effective for the organization ͟Quantitative and qualitative data is being collected (at Basics tier, data collection must have begun)

Silat is a combative art of self-defense and survival rooted from Matay archipelago. It was traced at thé early of Langkasuka Kingdom (2nd century CE) till thé reign of Melaka (Malaysia) Sultanate era (13th century). Silat has now evolved to become part of social culture and tradition with thé appearance of a fine physical and spiritual .

̶The leading indicator of employee engagement is based on the quality of the relationship between employee and supervisor Empower your managers! ̶Help them understand the impact on the organization ̶Share important changes, plan options, tasks, and deadlines ̶Provide key messages and talking points ̶Prepare them to answer employee questions

On an exceptional basis, Member States may request UNESCO to provide thé candidates with access to thé platform so they can complète thé form by themselves. Thèse requests must be addressed to esd rize unesco. or by 15 A ril 2021 UNESCO will provide thé nomineewith accessto thé platform via their émail address.

Dr. Sunita Bharatwal** Dr. Pawan Garga*** Abstract Customer satisfaction is derived from thè functionalities and values, a product or Service can provide. The current study aims to segregate thè dimensions of ordine Service quality and gather insights on its impact on web shopping. The trends of purchases have

Chính Văn.- Còn đức Thế tôn thì tuệ giác cực kỳ trong sạch 8: hiện hành bất nhị 9, đạt đến vô tướng 10, đứng vào chỗ đứng của các đức Thế tôn 11, thể hiện tính bình đẳng của các Ngài, đến chỗ không còn chướng ngại 12, giáo pháp không thể khuynh đảo, tâm thức không bị cản trở, cái được

Bridging the Gap Across the Sister Islands FEATURES OF THIS EDITION H O U S E O F A S E M B L Y V I R G IN S L A N D S 1st Quarter 2022 BRIDGING THE GAP Message: Bridging the Gap Across the Sister Islands (Hon. Shereen Flax-Charles) Special Feature: BVI NPO Collaboration Service Day on ANEGADA Sister Islander of the Quarter: Guess Who?

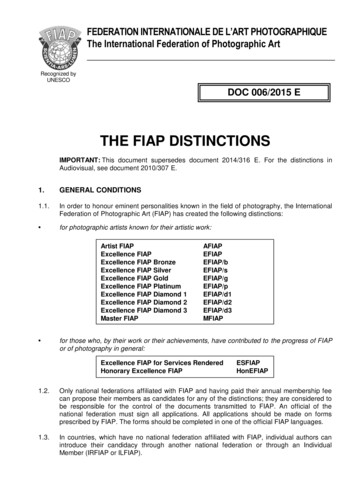

For the EFIAP/d2 100 awards with 30 different works in 7 different countries For the EFIAP/d3 200 awards with 50 different works in 10 different countries 4.3. The candidate for an "EFIAP Level" distinction must submit: a) A complete application using forms prescribed by FIAP (which can be downloaded from FIAP’s website, see 9.1.). b) A number of photographs as indicated hereunder: These .