LM FI HTOERY EARLY FILM THEORIES IN ITALY IN MEDIA

men, psychologists, government offi- and media studies at Yale University.cials, and philosophers react to the ad- SILVIO ALOVISIO is assistant professor ofvent of cinema? How did they develop afilm at the University of Torino.common language to contextualize anLUCA MAZZEI is assistant professor ofEDITED BY FRANCESCO CASETTIHow did Italian writers, scholars, clergy- FRANCESCO CASETTI is professor of filmWITH SILVIO ALOVISIO AND LUCA MAZZEIFILM THEORYHISTORYIN MEDIAinvention which had broken from estab- film at the University of Rome ‘Tor Ver-EARLY FILM THEORIES IN ITALY1896-1922lished cultural norms and categories ofgata’.thought? This anthology offers a previously unpublished collection of theirbroad and diverse social discourses,translated into English for the first time.The result is a rich and compelling examination of Italian culture between1890 and 1930 as it comes to terms withdisruptive change and enlists cinema inthe drive toward modernization.I S B N 978-90-896-4855-6AU P. nl9 789089648556FILM THEORYHISTORYIN MEDIAEARLY FILM THEORIES IN ITALY1896-1922EDITED BY FRANCESCO CASETTIWITH SILVIO ALOVISIO AND LUCA MAZZEI

Early Film Theories in Italy, 1896–1922

Film Theory in Media HistoryFilm Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoreticalfoundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well asanthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory.Adopting a historical perspective, but with a firm eye to the further developmentof the field, the series provides a platform for ground-breaking new research intofilm theory and media history and features high-profile editorial projects thatoffer resources for teaching and scholarship. Combining the book form withopen access online publishing the series reaches the broadest possible audienceof scholars, students, and other readers with a passion for film and theory.Series editorsProf. Dr. Vinzenz Hediger (Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany), WeihongBao (University of California, Berkeley, United States), Dr. Trond Lundemo(Stockholm University, Sweden).Editorial Board MembersDudley Andrew, Yale University, United StatesRaymond Bellour, CNRS Paris, FranceChris Berry, Goldsmiths, University of London, United KingdomFrancesco Casetti, Yale University, United StatesThomas Elsaesser, University of Amsterdam, the NetherlandsJane Gaines, Columbia University, United StatesAndre Gaudreault, University of Montreal, CanadaGertrud Koch, Free University of Berlin, GermanyJohn MacKay, Yale University, United StatesMarkus Nornes, University of Michigan, United StatesPatricia Pisters, University of Amsterdam, the NetherlandsLeonardo Quaresima, University of Udine, ItalyDavid Rodowick, University of Chicago, United StatesPhilip Rosen, Brown University, United StatesPetr Szczepanik, Masaryk University Brno, Czech RepublicBrian Winston, Lincoln University, United KingdomFilm Theory in Media History is published in cooperation with the PermanentSeminar for the History of Film Theories.

Early Film Theories in Italy, 1896–1922Edited byFrancesco Casetti withSilvio Alovisio and Luca MazzeiAmsterdam University Press

Published with the support of MiBACResearch in collaboration with Museo Nazionale del Cinema, TorinoUnder the Aegis of Consulta Universitaria CinemaCover illustration: Cover of the Film Journal La conquista cinematografica, August 1921Cover design: Suzan BeijerLay-out: Crius Group, HulshoutAmsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada bythe University of Chicago Press.isbne-isbndoinur978 90 8964 855 6978 90 4852 710 610.5117/9789089648556670Creative Commons License CC BY NC 0)All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam, 2017Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part ofthis book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted,in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise).

Table of ContentsThe Throb of the Cinematograph Francesco Casetti11Section 1Cinema and Modern Life Francesco Casetti35Cinematography 42EdipiThe Philosophy of Cinematograph 47Summertime Spectacles: The Cinema 51Why I Love the Cinema 55The Movie Theatre Audience 57The Art of Celluloid 60The Triumph of the Cinema 66The Death of the Word 75Giovanni PapiniGaioMaffio MaffiiGiovanni FossiCrainquebilleRicciotto CanudoFausto Maria MartiniSection 2Film in Transition 83The Museum of the Fleeting Moment 91The Woman and the Cinema 95Darkness and Intelligence 98Francesco CasettiLucio d’AmbraHaydéeEmanuele Toddi

A Spectatrix is Speaking to You 102Motion Pictures in Provincial Towns 105Cinematic Psychology 111The Cinematograph Doesn’t Exist 117The Cinema: School of the Will and of Energy 123The Close-up 135The Soul of Titles 140Matilde SeraoEmilio ScaglioneEdoardo ColiSilvio d’AmicoGiovanni BertinettiAlberto OrsiErnesto QuadroneSection 3Cinema at War 147The War, from Up Close 156That Poor Cinema. 160Families of Soldiers 164War for the Profit of Industry 168The War and Cinematograph 171Max Linder Dies in The War 173Cinema of War 176Luca MazzeiNino SalvaneschiRenato GiovannettiLuigi LucatelliRenato Giovannettig. pr.Lucio d’AmbraSaverio Procida

Section 4Politics, Morality, Education 183The Motion Pictures and Education 197The Intuitive Method in Religious Education 205The Cinema and Its Influence on the Education of the People 213The Cinematograph in the Schools 217Speech at the People’s Theatre 224Cinema for the Cultivation of the Intellect 237Educational Cinema 244Silvio AlovisioDomenico OranoRomano CostettiGiovanni Battista AvelloneFrancesco OrestanoVittorio Emanuele OrlandoAngelina BuracciEttore FabiettiSection 5Film, Body, Mind 255Collective Psychology 268Silvio AlovisioPasquale RossiAbout Some Psychological Observations Made During FilmScreenings 273Mario PonzoConcerning the Effects of Film Viewing on Neurotic Individuals 278The Ongoing Battle between Gesture and Word 286Giuseppe d’AbundoMariano Luigi PatriziThe Cinematograph in the Field of Mental Illness and Criminality:Notes 290Mario Umberto Masini, Giuseppe VidoniCinema and Juvenile Delinquency Mario Ponzo297

Section 6The Aesthetic Side 307Problems of Art: Expression and Movement in Sculpture 318Scenic Impressionism 321The Aesthetics of Cinema 325The Poetics of Cinema 329Manifesto for a Cinematic Revolution 333Theatre and the Cinema 339The Futurist Cinematography 341In the Beginning Was Sex 346Rectangle-Film (25 x 19) 348The Proscenium Arch of My Cinema 353My Views on the Cinematograph 359Meditations in the Dark 368Silvio Alovisio and Luca MazzeiCorrado RicciSebastiano Arturo LucianiGoffredo BellonciSebastiano Arturo LucianiGoffredo BellonciAntonio GramsciF.T. Marinetti, Bruno Corra, Emilio Settimelli, Arnaldo Ginna,Giacomo Balla, Remo ChitiAntonio GramsciEmanuele ToddiAnton Giulio BragagliaLucio d’AmbraMichele BiancaleSection 7Theory in a Narrative Form 373Colour Film 381At the Cinema 386Luca MazzeiRoberto TanfaniLuigia Cortesi

A Phantom Pursued 390Miopetti’s Duel 398Alberto LumbrosoAldo BorelliPamela-Films 405Guido GozzanoFeature Film 411Me, Rirì, and Love in Slippers 421A Cinematic Performance 427Life, a Glass Theatre 434The Shears’ Reflection 444Pio VanziLuciano DoriaFederigo TozziPier Maria Rosso di San SecondoGuido GozzanoSources 450Author Biographies 455General Bibliography 490Acknowledgements 505About the Editors 507Index of Names 508Index of Concepts 513Index of Films 517

The Throb of the CinematographFrancesco CasettiThere is one nuisance, however, that does not pass away. Do you hear it? Ahornet that is always buzzing, forbidding, grim, surly, diffused, and never stops.What is it? The hum of the telegraph poles? The endless scream of the trolleyalong the overhead wire of the electric trams? The urgent throb of all thosecountless machines, near and far? That of the engine of the motor-car? Of thecinematograph?‒ Luigi Pirandello, Shoot!‘Theories’ before TheoryThis book assembles 60 texts on cinema that appeared in Italy between 1896and 1922, most of which are printed here in English translation for the firsttime.1 The texts are quite varied in nature: editorials from daily newspapers;essays from illustrated magazines; commentaries in film journals; medicaland scientific reports; and fictional stories. The attitudes expressed withinthem are likewise quite varied: some pieces interrogate cinema from thestandpoint of its novelty; others express perplexity, seeing it as a threat toestablished values; others still are descriptions and reflections from critics, screenwriters, and directors interested in understanding how cinemafunctions or should function. Taken as a whole, this ensemble of texts helpsus to grasp the discourse around cinema that was emerging in the firsttwo decades of the twentieth century. We might also say that it constitutesthe core of Italian ‘film theory’ between the late 1890s and the early 1920s,provided that we clarify precisely what we mean by this term.Early ‘theories’ do not possess those characteristics that the great reflections on film from the mid-1920s onward have made us accustomedto—whether in Italy or in the rest of the world. For example, they do notemerge from systematic thought carried out in books and essays. Instead,they are usually sporadic interventions, related to current events or culturalpolemics, and are printed in daily newspapers, promotional journals, illustrated papers, and works of fiction. Only in the late 1910s did the successof sophisticated film magazines provide some sort of point of convergence;and only at the very beginning of the 1920s was there an attempt at a moreorganized study, such as Sebastiano Arturo Luciani’s Verso una nuova arte

12 Fr ancesco Casetti(Towards a New Art), published in 1921. Furthermore, the authors are notindividuals whose research deals entirely or even predominantly with cinema; rather, they are journalists, intellectuals, or writers on a wide varietyof subjects, for whom cinema is only one of many interests.2 Again, only atthe end of the 1910s do we see the by-lines of Sebastiano Arturo Luciani,Lucio d’Ambra, and Emanuele Toddi recur. At the same time, there is nota ‘discipline’ as a frame of reference that clearly outlines how and whycinema should be examined; instead, the contributions respond to a rangeof different motivations, from simple curiosity about a recent invention toobservations of the effects that films have upon social life. Finally, suchdiscursive production seldom calls itself theory; when it does, it is withreticence. This is the case with Luciani, who, in a text written in 1919, ‘Loscenario cinematografico’ (‘The Cinematographic Script’), although heassigns theoretical status to his ruminations, acknowledges that they canraise suspicion, and tries to dissolve the distrust by practically applying hisideas.3 The word theory would become relatively common only in the firsthalf of the 1920s, especially in France, Germany, and the US, as a frameworkin the broader attempt to define how cinema works at different levels. 4Nonetheless, if it is true that early ‘theories’ (in quotation marks) arenot the same as classical theory (without quotation marks), it is also truethat they respond to a need that classical theory would continue to takeinto account, even when its overt goal was to describe the basic laws of themedium. They share the need to provide an image of cinema that facilitatesits social comprehension and acceptance. Indeed, the main concern of early‘theories’ is precisely to offer a definition of a phenomenon that, at firstsight, seems puzzling and even scandalous. How can one grasp an apparatusthat seems to capture the fleeting moment and ensure the permanenceof life? How can one justify a machine with a gaze that goes beyond human capacities? How can one adapt to something that glorifies ubiquity,simultaneity, speed, and details? And how can the enormous success ofcinema be explained? The early ‘theories’, despite their sporadic character,quasi-anonymous writers, lack of a clear ‘method’, and hesitation towardself-designation, respond to the need for a practical and shared definitionof a phenomenon that challenges our expectations and our habits. In thissense, early ‘film theories’ do not have the character of scientific theory;rather, they are similar to those personal accounts that we formulate tomake sense of our daily actions. Described by ethnomethodology as a keycomponent of our social lives,5 accounts epitomize the ways membersof a community signify, describe, or explain the properties of a specificsocial situation in order to clarify and share its meaning. Likewise, early

The Throb of the Cinematogr aph 13theories seek to make what at first might appear ambiguous and strangeinto something comprehensible and graspable: they show what cinema isand how we encounter it; what distinguishes it and how we can react to it;what it can offer us and why we must accept it. The result of all of this is a‘public image’ of cinema that functions as both definition and legitimation.6The status of early film ‘theory’ as an account—or even as a gloss—explains why it so often appears in disguise, as if it were something ‘other’than a theory. Indeed, even if we limit ourselves to texts included in thisanthology, ‘theories’ appear in the form of editorials, such as the ones signedby Giovanni Papini, Adolfo Orvieto, and Enrico Thovez in the dailies LaStampa (The Press) and Corriere della Sera (Evening Courier); or of culturalreports, such as Ricciotto Canudo’s ‘Trionfo del cinematografo’ (‘Triumphof the Cinematograph’); or as political interventions such as those byVittorio Emanuele Orlando and Antonio Gramsci; or as letters written tonewspapers, such as the one by Giovan Battista Avellone, former GeneralProsecutor at the Appeals Court in Rome; or as pedagogical essays, such asDomenico Orano’s ‘Il cinematografo e l’educazione’ (‘The Motion Picturesand Education’); or as scientific reports, such as those by experimentalpsychologist Mario Ponzo; or as clinical observations, such as those by theneurologist Giovanni d’Abundo; or finally as fiction, written by authors suchas Guido Gozzano, Federigo Tozzi, and Aldo Borelli. And the variety of thetexts is even wider still: ‘theory’ can surface in reviews, in interviews, andeven in self-portraits written by professionals. There are also full-blownessays dedicated to cinema, especially near the end of the 1910s, by authorslike Sebastiano Arturo Luciani and Goffredo Bellonci (included in thisanthology), but this form would become dominant only midway through the1920s. In the first two decades of the century, ‘theory’ is distributed acrossall the fields and divisions of social discourse: only this sort of presenceallows for the true ‘accountability’ of cinema.To this diversity of formats corresponds a variety of themes, not one ofwhich is exclusive to a single discursive typology. Just to mention a few:cinema produces new forms of perception and reflection, as stressed bythe fiction writer Pio Vanzi and the psychologist Mario Ponzo. It has aspecial ability to reflect new lifestyles that reconfigure both the structureof social relationships and the notion of subjectivity, as underscored by thephilosopher Giovanni Papini and the neurologist Giuseppe d’Abundo. Itopens up new aesthetic horizons, in which the value of art works dependsnot only on their intrinsic quality, but on their relationship to consumption, as highlighted by the art critic Enrico Thovez and the philosopherand pedagogue Francesco Orestano. It marks the advent of the new urban

14 Fr ancesco Casettimasses as modern nations’ social and historical protagonists, as stressed bycolumnist Angiolo Orvieto and commentator Giovanni Fossi. It generatessocial risks, but also offers great possibilities for the advancement of themasses, as suggested by Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (in a serious way) andEmilio Scaglione (in an ironic one). ‘Theories’ tried to parse the noveltyof cinema both as a whole and in its more localized aspects through anextensive circulation of questions and remarks.Attempts to define what cinema is often merge with an effort to detectwhat it will be, or can be, or must be. Hence the wide variety of perspectivesfrom which cinema is approached: ‘theories’ address not only cinema’sactuality, but also its possibilities, even its purported obligations. Thisis true in the obvious case of ‘La cinematografia futurista’ (‘The FuturistCinematography’), a manifesto by the most relevant Italian avant-gardemovement, which heralds a cinema that will never find its full realization (Marinetti and others 1916); but also of ‘Orizzonti del cinema avvenire’(‘Horizons of Cinema to Come’), in which Giuseppe Fossa describes a cinemaof the future that is amazingly akin to television or even Skype.7 ‘Theory’was often a ‘promise’ if not a ‘dream’ of cinema.8Given the wide variety of formats, topics, and stances, no single textmanaged to dictate the terms of the debate. There are no key contributionsfunctioning as paradigmatic or universal points of reference, as would bethe case in the late 1920s with Sebastiano Arturo Luciani’s L’antiteatro (TheAnti-Theatre) or in the early 1930s with Alberto Consiglio’s Cinema. Arte elinguaggio (Cinema: Art and Language).9 Undoubtedly, certain texts gainedwidespread attention and resonance, and were paraphrased in subsequentcontributions (often without proper acknowledgment, as occurred withRicciotto Canudo’s essay ‘Triumph of the Cinematograph’, published inlate December 1908 in the Florentine newspaper Il Nuovo Giornale (TheNew Daily) and then republished, almost verbatim but under a pseudonym,in La rivista fono-cinematografica (Phono-cinematographic Magazine) inJanuary and February 1909.10 We do not, however, find a ‘canon’ in the propersense of the word. Instead, we find a kind of muddled, crowded discourse,where different contributions emerge, side by side, even overlapping, in anapparently confused but effective dialogue with each other. For instance,within the timeframe of a few months, Giovanni Papini celebrated cinema’s popularity in a widespread daily, while Gualtiero Ildebrando Fabbridescribed and fictionalized film audiences in a book produced as a giftfor the most assiduous spectators of a cinema in Milan. At the same time,Angiolo Orvieto reported in the daily Corriere della Sera on the differencesbetween cinema and theatre, while in the competing daily, La Stampa,

The Throb of the Cinematogr aph 15Enrico Thovez commented on cinema’s affinity with contemporary life;Ricciotto Canudo, in correspondence from Paris, highlighted cinema’sdistinct aesthetic traits, while Mario Ponzo, in a scientific report, focusedon the physiology of film reception. This amounts to an impressive circuitof discussion, without a clear and singular centre; Michel Foucault wouldcall it a ‘discursive formation.’11 It is within this circuit that the image ofcinema takes shape: an image whose contours are continually sharpenedand which becomes the public portrait of the new invention.Beginning midway through the 1920s in Italy and in many other countries, the theory of cinema would begin to arrange and order this ratherchaotic circuit of discourses. More precise methodologies would emerge,key themes would become more widely shared, and the sketch of a canonwould take shape. The need to define cinema in a practical way, however,would continue, albeit in connection with more specific contexts. What isthe cinema as an art? As a national industry? As a language? Even withina more clearly-developed framework, the need for an ‘account’ would notcompletely disappear. This need fully re-emerged in recent years, at whichpoint the convergence between different media obligated cinema to radically transform itself

Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and

1920 - Nitrate negative film commonly replaces glass plate negatives. 1923 - Kodak introduces cellulose acetate amateur motion picture film. 1925 - 35mm nitrate still negative film begins to be available and cellulose acetate film becomes much . more common. 1930 - Acetate sheet film, X-ray film, and 35mm roll film become available.

Drying 20 minutes Hang film in film dryer at the notched corner and catch drips with Kim Wipe. Clean-Up As film is drying, wash and dry all graduates and drum for next person to use. Sleeve Film Once the film is done drying, turn dryer off, remove film, and sleeve in negative sleeve. Turn the dryer back on if there are still sheets of film drying.

2. The Rhetoric of Film: Bakhtinian Approaches and Film Ethos Film as Its Own Rhetorical Medium 32 Bakhtinian Perspectives on the Rhetoric of Film 34 Film Ethos 42 3. The Rhetoric of Film: Pathos and Logos in the Movies Pathos in the Movies 55 Film Logos 63 Blade Runner: A Rhetorical Analysis 72 4.

Film guide 5 Film is both a powerful communication medium and an art form. The Diploma Programme film course aims to develop students' skills so that they become adept in both interpreting and making film texts. Through the study and analysis of film texts and exercises in film-making, the Diploma Programme film

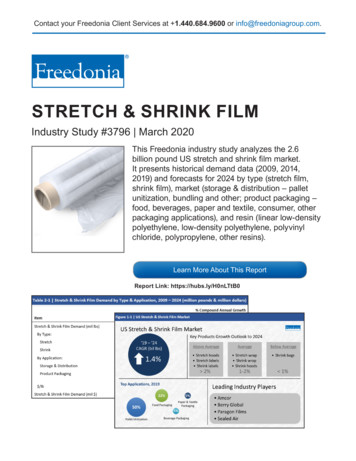

3. Stretch Film 24 Key Findings 24 Stretch Film Demand 25 Stretch Film Production Methods (Cast, Blown) 26 Stretch Film Resins 28 Stretch Film Products 30 Demand by Product 30 Stretch Wrap 31 Stretch Hoods 32 Stretch Sleeve Labels 34 Stretch Film Applications 35 Demand by Application 35 Pallet Unitization (Mach

2a. OCR's A Level in Film Studies (H410) 7 2b. Content of A Level in Film Studies (H410) 8 2c. Content of Film History (01) 10 2d. Content of Critical Approaches to Film (02) 17 2e. Content of non-examined assessment Making Short Film (03/04) 25 2f. Prior knowledge, learning and progression 28 3 Assessment of A Level in Film Studies 29 3a.

4 EuropEan univErsity and film school nEtworks 2012 11 a clEar viEw German film and television academy (dffb), Berlin dE film and tv school of the academy of performing arts (famu), prague cZ london film school (lfs) uk university of theatre and film, Budapest hu pwsftvit - polish national film, television & theater school, lodz pl 12 adaptation for cinEma - a4c

Easily build API composition across connectors SAP Cloud Platform Integration SAP Cloud Platform API Management SAP Workflow Services SAP Data Hub SAP Cloud Platform Open Connectors Simplifying integration and innovation with API-first approach in partnership with Cloud Elements