Contents Page: NZJER, 2017, 42(2) - Nzjournal

Contents Page: NZJER, 2017, 42(2)NameFiona Edgar, IanMcAndrew, AlanGeare and PaulaO’KaneBronwyn NealTaylor SizemoreTitleOccupational Health & Safety:introduction to the collectionHealth and Safety At Work Act 2015:Intention,ImplementationAndOutcomes in the Hill Country LivestockFarming IndustryManagerial attitudes toward the Healthand Safety at Work Act (2015): Anexploratory study of the ConstructionSectorFelicity Lamm, DaveMoore, Swati Nagar; Under Pressure: OHS of VulnerableErling Rasmussen and Workers in the Construction IndustryMalcolm SargeantChristopher PeaceThe reasonably practicable test andwork health and safety-related riskassessmentsIan McAndrew, FionaEdgar and TrudySullivanDiscipline, Dismissal, and the DemonDrink: An Explosive Social CocktailErling RasmussenEditorial: Employment relations and the2017 general electionBarry Foster and Erling The major parties: National’s andRasmussenLabour’s employment relations policiesPeter Skilling and New Zealand’s minor parties and ERJulienne Molineauxpolicy after 110-128

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 1-4Occupational Health & Safety: introduction to the collectionFIONA EDGAR, IAN McANDREW, ALAN GEARE and PAULA O’KANEUniversity of OtagoAt 3.44 in the afternoon of Friday November 19, 2010, an explosion in the Pike River Mine onthe West Coast of Aotearoa New Zealand’s South Island trapped 29 men underground.Following three additional explosions over the next 10 days, police accepted that the men couldnot be alive and attention turned from rescue to an unsuccessful effort at recovery. The disasterremains on the public consciousness seven years later, as families of the victims continue topress authorities for the mine to be entered and the bodies of their lost men finally recovered.The Pike River disaster has also affected the public consciousness in another way as well. Interms of the loss of human life, it was amongst the most costly workplace episodes in NewZealand history. In looking for explanations, attention quickly turned to weak mine safetyregulations and inadequate mine safety inspections, which in turn led to a wider concern withthe general inadequacy of New Zealand’s Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) regime.These inadequacies were reinforced when an earthquake hit Christchurch for the second timein February 2011, resulting in further loss of life, including many people at work. The urgencyto do something increased.New Zealand is not alone in experiencing recent workplace tragedies, and OHS is increasinglyrecognised as an important Employment Relations (ER) issue, with inherent obligations onemployers and the State to keep workers safe. In developed countries, a key contributoryelement for the escalation of occupational illness, injuries and death has been the diminishingrole of unions as workers’ advocates, with neither government regulation nor employer ERinitiatives moving sufficiently or sufficiently quick to fill the void. The Pike River disaster andits aftermath served to highlight two important realities: by comparison with others, NewZealand’s occupational accident and injury rates were high; and employers were notsufficiently attentive to or held accountable for the welfare of their workers.Impelled by a ground swell of public opinion, change was deemed urgently necessary andemployer groups in conjunction with the State belatedly swung into action. This was evidencedby the commissioning and development of a series of working papers and reports (e.g. TheReport of the Independent Taskforce on Workplace Health and Safety, April 2013; Wellness inthe Workplace, 2013; and Workplace Health and Safety, 2012), with this work subsequentlyinforming a revamping of OHS legislation. In April of 2016, the Health and Safety at WorkAct (HSWA, 2015), which is explicitly aimed at securing “the health and safety” of workplacesand their employees came into force. A new regulatory agency, WorkSafe New Zealand, wasestablished by the HSWA.This Act has raised a lot of questions about employers’ obligations and liabilities in the OHSarena, and it is against this backdrop that we were delighted to be invited by the Editors of theNZJER to convene this collection of papers on aspects of the broad and multi-faceted field ofworkplace health and safety. We see this collection as a beginning that urgently invites furtherresearch attention to this vital area of study.2

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 1-4Primary industries remain key drivers of the New Zealand economy and to some extent lifestyleas well, and the first paper in our collection illustrates the difficulties of adequately regulatingfor worker safety in this arena, and the complexities of regulating for worker safety across adiverse economy. Bronwyn Neal highlights peculiarities of hill country farming as an industryfrom an OHS perspective, including the uncontained nature of the workplace, the involvementof family labour and the integration of workplace with lifestyle, and the long tradition of publicaccess to the privately-held terrain of the high country. Neal contends that, in the hill countryfarming sector, the Act has prompted peripheral issues to become the main focus, thusdetracting attention away from the more serious risks experienced in this sector. She points toa contradiction of enforcement, engagement, and education functions of the newly-establishedState regulatory agency, WorkSafe, as undermining its effectiveness in this iconic NewZealand industry.Construction is another vital and high profile industry in New Zealand, both because of ageneral shortage of housing stock, particularly in Auckland, the country’s largest market, anddue to the reconstruction continuing in Christchurch and the wider Canterbury area followingthe earthquakes of 2010, 2011 and subsequently. The HSWA places a lot of emphasis onmanagerial commitment and worker involvement as key pillars of a rejuvenated drive foroccupational safety, and the second paper by Taylor Sizemore examines this focus in theconstruction industry. Sizemore finds commitment to improving workplace health and safetyis being addressed largely through enhanced employee involvement; however, the efficacy ofthese initiatives may be thwarted by the complacent attitudes of workers. Nonetheless, hisinterviews with construction industry managers responsible for OHS within their organisationsrevealed some positive changes in the safety culture of firms in the industry and providedreasons for optimism.We stay in the construction industry for our third paper, but with a wholly different focus. Aspecial issue on OHS would not be complete without a review of worker vulnerability and thisarticle takes up this important issue. Using the catalyst of the Christchurch earthquakes andtheir subsequent impact on the construction industry, Felicity Lamm, Dave Moore, SwatiNagar, Erling Rasmussen, and Malcolm Sargeant apply Quinlan and Bohle’s ‘Pressures,Disorganization and Regulatory Failure’ model to probe issues pertaining to the OHS and subcontracted workers in this industry. They propose a model which recognises the interests ofmultiple stakeholders, combined with the fostering of intra-industry collaboration, as potentialmechanisms for enhancing the outcomes of this vulnerable worker group.A cornerstone of past and current OHS legislation in New Zealand, as in a number of otherjurisdictions, is and has been the obligation on employers to take ‘reasonably practicable steps’to ensure the safety of workers (and others). This involves the interpretation of those terms andthe application of that principle to the facts and circumstances of particular situations. As such,the obligation has been at the contentious centre of academic discourse and, of course, of manyadjudicated cases as well. Continuing with the legislative theme, our fourth paper byChristopher Peace explores the origins of the ‘reasonably practicable test’ both in common lawand in New Zealand’s and Australia’s health and safety legislation and asks what a riskassessment under these current legislative frameworks might look like.For our final paper, we take a different approach and consider New Zealand’s problematicdrinking culture and its confounding impact on the workplace, examined in an exploratorystudy by Ian McAndrew, Fiona Edgar and Trudy Sullivan. It is accepted that alcohol serves asometimes functional purpose as a social lubricant in many work-related and workplace3

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 1-4situations. However, research has also established the harmful effects of workers intoxicationon the job, reporting for work ‘hungover,’ or workers otherwise impacted by inappropriatealcohol consumption by themselves, their employers, their co-workers, or others with whomthey interact in their employment. Drug and alcohol consumption are now recognised asmodern day threats to workplace health and safety. Our final paper examines one aspect ofalcohol in the workplace as an OHS danger, invoking the same employer and workerobligations that attach to any threat to workplace safety. The focus is workplace social events,including after-work drinks and the iconic ‘work Christmas party’; a source of so-muchpleasure and pain in so many workplaces. McAndrew et al examine a number of significantbehavioural issues that can occur at these events, including acts of physical aggression andsexual harassment, and highlight the lessons to be gleaned from this study.In concluding this introduction, we wish to redraw attention to the broad range of issues whichfall within the gamut of OHS, noting that the breadth of topics addressed within this specialissue afford testament to this. We thank the authors for their valuable contributions, andencourage others to contribute to this vital area of regulatory and ER policy and practice.4

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 5-21Health and Safety at Work Act 2015: Intention, Implementationand Outcomes in the Hill Country Livestock Farming IndustryBRONWYN NEAL*AbstractThe recently enacted Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 applies across all New Zealandindustries. The unique workplace environment and industry culture of the hill countrylivestock farming sector makes application, implementation and enforcement of the Act inthis context uniquely challenging. In contrast to other industries, hill country livestockfarming has an uncontained workplace complicated by family and public involvement.WorkSafe, as a “fair, consistent and engaged” regulator, seeks to establish health and safetyas one of the industry’s key cornerstones, alongside lifestyle, profit and sustainability.Results to date have been undermined by WorkSafe’s conflicting enforcement, engagementand education functions. There is a perceived misplaced focus on enforcement of lowprobability, peripheral hazards rather than the key risks that cause accidents. This paperexplains the implications of significant changes under the Act for the industry. It alsorecommends legislative adaptations to address the inadequacies of the farming exceptionin s 37. An alternative WorkSafe strategy that focuses on effecting compliance throughsupply chain demand and economic drivers rather than enforcement is outlined.Key words: Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, hill country livestock farming, healthand safety, WorkSafe, workplaceIntroductionThis paper is a case study on the impact of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015(HSWA) within the hill country livestock farming industry. This industry warrants specificconsideration because the unique culture and workplace environment makes applicationand enforcement of the Act within this context distinctly difficult. As the industry isstrongly represented in New Zealand’s workplace injury and fatality rates, WorkSafe willnot achieve key performance indicators without addressing health and safety deficiencieswithin this sector. As a result, the industry is currently subject to intense enforcement andregulatory attention. The object of this article is to assess the application, enforcement andcurrent effectiveness of the Act within this industry and determine necessary modificationsto the current regime. This paper highlights relevant changes under the new Act. The*Bronwyn Neal, LLBHONS/BCOM student at Victoria University of Wellington. This is an abridged versionof the paper submitted for LAWS489 Honours Research Essay. In grateful acknowledgement of his help andassistance, I would first and foremost like to thank my supervisor Gordon Anderson. I also acknowledge theagricultural advice of Derek Neal, Stephen Franks for initial ideas, Ayla Ronald for her practical experienceand Al McCone for providing an insight into WorkSafe5

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 5-21imbalance between enforcement and encouragement with a particular focus on WorkSafe’scurrent implementation strategy is addressed. Difficulties inherent in the legislation whenapplied to the industry are identified and legislative and strategic changes recommended.I Background to the HSWA and WorkSafeThe loss of 29 miners in the Pike River mine tragedy on 19 November 2010 highlightedmultiple workplace health and safety issues in New Zealand (Royal Commission on thePike River Coal Mine Tragedy, 2012). The ensuing comprehensive response includedenacting the HSWA and forming WorkSafe New Zealand.WorkSafe is a New Zealand Crown entity, established in 2013, to replace its predecessorthe Occupational Safety and Health Service (WorkSafe New Zealand Act 2013). WorkSafehas a tripartite function to safeguard health and safety in New Zealand workplaces througheducation, engagement and enforcement (WorkSafe New Zealand, 2016a)II The Industry Requires a Degree of Separate TreatmentHill country livestock farming is an industry sector of New Zealand agriculture.Agriculture accounts for 38 per cent of workplace fatalities since 2011 and seven per centof workplace serious harm notifications (WorkSafe New Zealand, 2016b). Researchsuggests disparity between the fatality rate and serious harm notifications is the result ofunder-reporting rather than the nature of agricultural accidents (Lovelock & Cryer, 2009).Under-reporting is likely driven by both “negation and denial of ill-health” and minimalcompensatory benefits for minor injuries (ibid: 23).Hill country livestock farming is a unique industry with a clearly distinguishable culture ofstoicism, pragmatism and self-sufficiency. Family and work are entwined and members ofthe public are frequently permitted gratuitous, often unsupervised, access to the workplace.The work is intensely physical and highly varied, requiring skilled use of variousmachinery and an acute awareness of the risks involved in unpredictable elements of theindustry, such as climate and stock handling. The whole farm is a potentially activeworkplace, with some parts worked only occasionally, often in remote and isolatedconditions. This strongly contrasts to other relatively contained workplaces, such asfactories and mines, in which the traditional health and safety model is designed to operate.Family members are often intimately involved in farm work and thereby exposed to thesame risks as workers. This complicates the formulation and implementation of workplacehealth and safety initiatives because industry receptiveness is not solely determined by theeffects proposed changes have on their businesses, the impact on family lifestyle is equallyrelevant. A pertinent example is WorkSafe guidance which prohibits carrying passengerson quad bikes (WorkSafe New Zealand, 2014a). This and similar rules not only affectworkers, but also significantly constrain the traditional family-work integration.The HSWA is drafted to apply universally across all industries and, consequently, itinadequately addresses the specific industry culture and interaction between the workplace,6

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 5-21family and public associated with hill country livestock farming. These unique featuresjustify industry specific regulation and legislative adaptations.III Key Features of the HSWAMultiple individuals within a workplace have the capacity to influence health and safetyrisks. The HSWA capitalises on this by converting potential into a positive obligation tocontrol and eliminate health and safety risks within the workplace as far as is “reasonablypracticable”. The “reasonably practicable” threshold is a known concept in New Zealandhealth and safety law because it was used to define “all practicable steps” in s 2A of theHealth and Safety in Employment Act 1992 (HSEA). While not immediately apparent fromthe s 22 definition, unlike the HSEA, the focus of the HSWA is on risks rather than hazards(McKenzie, 2016; Schmidt-McCleave & Shortall, 2016). The initially suggested definitionof “risk” was “the possibility that death, injury, or illness might occur when a person isexposed to a hazard” (Health and Safety Reform Bill (192-2): 30). However, the SelectCommittee decided against including any definition “to encourage people to consider whatrisk means to them, in their particular circumstances” (Health and Safety Reform Bill (1922): 5).A Duty Holders and Their ObligationsThe three main duty holders under the Act are persons conducting a business or undertaking(PCBUs), workers, and others present on the workplace. This is a change in terminologyfrom the “employer” and “employee” categories of the HSEA (s 6). This change will affectparticular industry business structures as discussed in part three/this section.The primary duty of care is the most onerous duty, requiring a PCBU to “ensure, so far asis reasonably practicable, the health and safety of workers who work for the PCBU whilethe workers are at work in the business or undertaking” (HSWA: s 36). A PCBU breachesthis duty by failing to ensure health and safety, irrespective of whether this failure resultsin an injury or fatality (Haynes v CI & D Manufacturing Pty Ltd, 1994). The change interminology from “employee” under the HSEA to “worker” is intended to make it clearthat people who are workers, though they may not be strictly classed as employees, areowed a primary duty of care (Health and Safety Reform Bill (192-2)). Federated Farmersnotes that this resolves the status of contractors (Federated Farmers as cited in Neal, 2016).A PCBU also owes a duty to people who are not workers to “ensure, so far as is reasonablypracticable, that the health and safety of other persons is not put at risk from work carriedout as part of the conduct of the business or undertaking” (HSWA: s 36(2)). This ismarginally more onerous than the corresponding duty under s 15 of the HSEA.Workers and other persons at the workplace are under correlative duties to take reasonablecare concerning health and safety towards themselves, others and to comply with policiesand instructions of PCBUs.The addition of a duty on others at the workplace ensures that everyone is compelled topartake in workplace health and safety (McKenzie, 2016). As a result, multiple individuals7

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2): 5-21often owe duties in relation to the same risk. In this situation, all duty holders are requiredto discharge their duties (HSWA: s 33).B Changes Under The HSWAThe class of people obliged to discharge a duty of care has widened, penalties increasedand PCBUs are required to undertake more worker involvement. Notwithstanding thesechanges the overall intention, enforcement potential and the nature of the duties are notmaterially different under the HSWA when compared with the HSEA. As discussed below,the noticeable increase in health and safety inspections and enforcement actions pre-datedthe HSWA coming into force and are instead the result of WorkSafe’s conception ratherthan legislative reform.1 Enforcement of the HSWAThe duties and o

New Zealand is not alone in experiencing recent workplace tragedies, and OHS is increasingly recognised as an important Employment Relations (ER) issue, with inherent obligations on employers and the State to keep

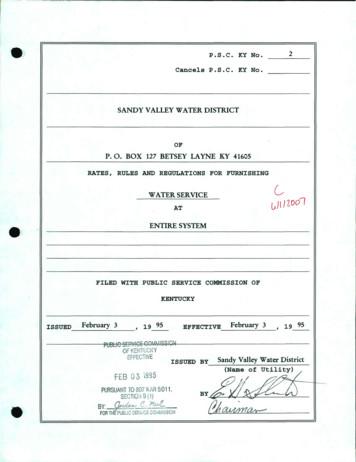

ef-fec1we issued by sandy valley water district ,-eb ri 7 '. ovh :- vi) hjj\j (name by -@- index page 1. page 2. page 3. page 4. page 5. page 6. page 7. page 8. page 9. page 10. page 1 1. page 12. page 13. page 14. page 15. page 16. page 17. page 18. page 19. page 20. .

The Lenape / English Dictionary Table of Contents A page 2 B page 10 C page 10 D page 11 E page 11 F no Lenape words that begin with F G page 14 H page 19 I page 20 J page 20 K page 21 L page 24 M page 28 N page 36 O page 43 P page 43 Q page 51 R no Lenape words that begin with R S page 51 T

Rational Rational Rational Irrational Irrational Rational 13. 2 13 14. 0.42̅̅̅̅ 15. 0.39 16. 100 17. 16 18. 43 Rational Rational Rational Rational Rational Irrational 19. If the number 0.77 is displayed on a calculator that can only display ten digits, do we know whether it is rational or irrational?

Set Manual Control Output and Brake Light Switches Initial Setup Test Drive & Adjustment Bench Test Troubleshooting Guide page 2 page 2 page 3 page 3 page 4 page 5 page 6 page 7 page 7 page 8 page 11 page 11 page 12 page 12 page 14 1. Drill 2. Drill bit, 5/16" 3. Phillips screwdriver 4. Pry tool TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTROLS & COMPONENTS TOOLS .

Cahier pédagogique À deux roues, la vie! DynamO Théâtre 2 page 3 page 3 page 3 page 4 page 4 page 5 page 5 page 5 page 6 page 7 page 8 page 9 page 10 page 11 page 12 page 12

ÌSprue Bushing MSB-A3530 Page 18 Page 18 Page 18 Page 19 Page 19 Page 19 Page 20 Page 20 Page 20 Page 21 Page 21 Page 21 Page 22 Page 22 Page 22 Page 23 MSB-B3030 MSB-C2520 MSB-D3030 MSB-E2520 MSB-F1530 MSB-G3520 MSB-H3530 . HOT CHAMBER S L GP GB GPO EP C SB SP CL ML MAIN PRODUCTS ITEM

thailand b2c e-commerce market 2017 publication date: april 2017 page 2 general information i page 3 key findings i page 4-5 table of contents i page 6 report-specific sample charts i page 7 methodology i page 8 related reports i page 9 clients i page 10-11 frequently asked questions i page 12 order form i page 13 terms and conditions

In the English writing system, many of the graphemes (letters and letter groups) have more than one possible pronunciation. Sometimes, specific sequences of letters can alert the reader to the possible pronunciation required; for example, note the letter sequences shown as ‘hollow letters’ in this guide as in ‘watch’, ‘salt’ and ‘city’ - indicating that, in these words with .