HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT - Home Alberta

HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENTHOW DO YOU ASSESS CLINICAL TRIALS (IN SURGERY)?MODULE 4Workshop ManualMarch 2006Surgery Strategic Clinical Network: Evidence Decision Support ProgramThis Project was funded by:Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (CCOHTA)

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?Revised March 2006Page ii of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?WELCOMEWelcome to the fourth module of six in a series on Health Technology Assessment (HTA).The primary objective of this fourth module and workshop is to provide you with an overviewof clinical trials in general and of how to assess clinical trials in surgery.We hope that the fundamentals presented in this module will not only assist you in your ownassessment of clinical trials in surgery, but also provide you with the tools required tocritically evaluate all clinical research in a sound, objective, and appropriate manner.We look forward to sharing this experience with you and your colleagues. Your feedback andcomments on both the module and workshop will be greatly appreciated! Please sendcomments to the Office of Surgical Research at osr@ucalgary.caPrepared by:Elizabeth Oddone PaolucciTyrone DonnonPaule PoulinThe HTA Education Team Members,Paule Poulin, PhDOffice of Surgical Research, Associate Director, Calgary Health RegionTyrone Donnon, PhDMedical Education & Research Unit, Assistant Professor, Faculty of MedicineElizabeth Oddone Paolucci, PhDMedical Education & Research Unit, Educational ConsultantNorm Schachar, MD, FRCSCOffice of Surgical Education, Director, Department of SurgeryAnita Jenkins, RN, BN, MNOffice of Surgical Education, Education Coordinator, Department of SurgeryDavid Sigalet, MD, PhD., FRCSCOffice of Surgical Research, Director, Department of SurgeryRevised March 2006Page iii of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?CONFLICT OF INTERESTConflict of interest is considered to be financial interest or non-financial interest, either director indirect, that would affect the research contained in a given report, or creation of asituation where a person’s judgment could be unduly influenced by a secondary interest suchas personal advancement. Indirect interest may involve payment which benefits a departmentfor which a member is responsible, but which is not received by the member personally, e.g.fellowships, grants or contracts from industry, industry sponsorship of a post or a member ofstaff in the department, industry commissioning of work.Based on the statement above, no conflict of interest exists with the author(s) and/orexternal reviewers of the fourth module.ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis Health Technology Assessment Module was prepared for the Department of Surgeryby the Office of Surgical Research, the Medical Education and Research Unit, and theOffice of Surgical Education and funded by the Canadian Office for HealthTechnology Assessment (CCOHTA), a National-based organization with a mandate tofacilitate the appropriate and effective utilization of health technologies within health caresystems across Canada. CCOHTA’s mission is to provide timely, relevant and rigorouslyderived evidence-based information to decision makers and support for the decision-makingprocesses. The HTA Team wishes to thank Ms. Darlene Bridger and Ms. Linda Davis for theiradministrative support.This Project was funded by:Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment(CCOHTA)Revised March 2006Page iv of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?TABLE OF CONTENTS1.0 OBJECTIVES . 12.0 INTRODUCTION . 23.0 TYPES OF CLINICAL TRIALS . 33.1 Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) . 43.2 Preclinical Trials . 53.3 Crossover Trials . 53.4 Multi-centere and International Clinical Trials . 63.5 Equivalence Trials . 63.6 Screening Trials . 63.7 Safety Trials . 73.8 Explanatory or Efficacy Trials . 73.9 Pragmatic or Effectiveness Trials . 83.10 Blinding or Masking Trials . 83.11 Placebo-Controlled . 94.0 PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE OF CLINICAL TRIALS AND ETHICS . 104.1 Phase I Study: Basic Pharmacological and Toxicology Information . 114.2 Phase II Study: Identify Dose Range of a Drug . 114.3 Phase III Study: Compare Effects of Different Treatments . 124.4 Phase 4 Study: Post-Marketing . 125.0 EVALUATION OF RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS . 135.1 Advantages and Disadvantages of RCTs . 135.2 Specific Obstacles to Randomized Controlled Trials (in Surgery) . 135.2.1 History145.2.2 Commercial Competition and Prestige155.2.3 Surgeons’ Equipoise155.2.4 Lack of Funding, Infrastructure, and Experience of Data Collection 155.2.5 Lack of Education in Clinical Epidemiology16Revised March 2006Page v of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?5.2.6 Rare Conditions and Life Threatening and Urgent Situations5.2.7 The Learning Curve5.2.8 Definition of Intervention and Quality Control Monitoring5.2.9 Development versus Research5.2.10 Patients’ Equipoise5.2.11 Blinding1616171718186.0 PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR CLINICAL RESEARCH (IN SURGERY) . 196.1 Audit Data Collection . 196.2 Continuous Performance Evaluation . 196.3 Conduct of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) . 206.4 Other Sources of Evidence. 207.0 CONCLUDING SUMMARY . 217.1 review of module objectives . 228.0 REFERENCES . 239.0 APPENDICES . 269.1 Appendix A: Clinical Trials Insight . 26Revised March 2006Page vi of 32

1.0 OBJECTIVESThe main goal of this Health Technology Assessment (HTA) module is to provide an overviewof how to assess clinical trials with a particular emphasis in surgery.By the end of this HTA module, participants will be able to:(1) Describe some of the types of clinical trials appearing in the medical literature,specifically:a. Randomized Controlled TrialsClinical Trials (Randomized or not)b. Preclinical Trialsc. Screening Trialsd. Crossover Trialse. Multi-center and International Clinical Trialsf. Equivalence Trialsg. Screening Trialsh. Safety Trialsi. Explanatory or Efficacy Trialsj. Pragmatic or Effectiveness Trialsk. Blinding or Masking Trialsl. Placebo-Controlled Trials(2) Identify the purpose and structure of clinical trials.(3) Discuss the advantages and disadvantages to conducting clinical trials.(4) Understand the obstacles to conducting clinical trials.(5) Propose a framework for clinical research in surgery.Page 1 of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?2.0 INTRODUCTIONIt is a generally accepted principle that the strength of a study depends on its design.Similarly, good design and statistical analysis underpins good-quality work relevant to healthtechnology assessment (White, Ashby, & Brown, 2000). The ability of Health TechnologyAssessments (HTAs) to answer questions about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness ofnew technologies relies on the availability of appropriate methodologies and statisticalanalyses (White, Ashby, & Brown, 2000). Various hierarchies of evidence have beenpresented, however, one commonality is that randomized controlled trials tend to be one ofthe strongest of study designs that produce sound sources of evidence.Medical practice is changing, and the change that involves using the medical literature moreeffectively in guiding medical practice is profound enough to be called a paradigm shift(American Medical Association, 1992). The foundations of the paradigm shift lie indevelopments in clinical research over the last 30 years. In 1960, the randomized clinical trial(RCT) was an oddity. It is now accepted that virtually no drug can enter clinical practicewithout demonstration of its efficacy in clinical trials (American Medical Association, 1992).Moreover, the same randomized trial method increasingly is being applied to surgicaltherapies and diagnostic tests (American Medical Association, 1992). Much of the statisticalliterature on study designs that relate to health technology assessment comes from clinicaltrials; there are relatively few publications that cover the more complex experimental designs,meta-analysis or studies of drug safety (White, Ashby, & Brown, 2000).Since Clinical Trials (CTs), in particular randomized clinical trials (RCT) are central to the workof many medical professionals and are believed to provide the most compelling evidence of acausal relationship between treatment and effect, it is important that they be wellunderstood. In the following section we begin our introduction of CTs.Revised March 2006Page 2 of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?3.0 TYPES OF CLINICAL TRIALSIn medicine, a clinical trial (also known as clinical research) is a research study with humanvolunteers with the aim of evaluating new drugs, medical devices, biologics, or otherinterventions to patients in strictly scientifically controlled settings is). Clinical trials are required for regulatory authority approvalof new therapies. Trials may be designed to assess the safety and efficacy of anexperimental therapy, to assess whether the new intervention is better than standardtherapy, or to compare the efficacy of two standard or marketed interventions. The trialobjectives and design are usually documented in a clinical trial protocol(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clinical trial; s).By a loose definition, studies that examine one group of people before and after treatmentcould be considered clinical trials (Quest, 2001). However, by the strictest definition, aclinical trial compares a group of people receiving the experimental treatment (i.e., thetreatment group) to a similar group of people who do not receive the treatment (i.e., thecontrol group (Quest, 2001). Usually the control group is given an inert substance (i.e.,placebo) so that any expectations participants may have about the experimental treatmentwill be the same in both groups and therefore theoretically will not influence the results(Quest, 2001). When the trial is finished, health differences between the two groups can beattributed to the treatment being tried instead of other factors, like the natural course of thedisease, positive expectations of the drug’s effects, age or gender (Quest, 2001).The major difference between clinical trials and epidemiological studies (e.g., cohort or casecontrol study) is that in clinical trials, the investigators manipulate the administration of a newintervention and measure the effect of that manipulation. In contrast, epidemiologicalstudies only observe associations (correlations) between the treatments experienced byparticipants and their health status or diseases (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clinical trial).Clinical trials may take on various forms. For instance, they may be randomized or not,placebo controlled or not, a crossover or parallel design, or multi-centered or of anexperimental design layout (White, Ashby, & Brown, 2000). Although not a complete listing,the following sections examine various types of clinical trials one may come across in themedical literature.Revised March 2006Page 3 of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?3.1 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL (RCT)In Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) participants are assigned by chance to separategroups that compare different treatments. Neither the researchers nor the participants canchoose which group. Using chance to assign people to groups means that the groups will besimilar and that the treatments they receive can be compared objectively. At the time of thetrial, it is not known which treatment is best. Both groups are followed up for a specifiedperiod and then groups are analyzed in terms of outcome defined at the outset. If thegroups are similar at the outset, any difference should be due to the intervention.The purpose of an RCT is to study interventions by objectively and fairly comparing theireffect in similar groups. To achieve this, it is important to take steps to guard against bias(MRC, 2003). Failure to randomize, lack of blinding, and differential exclusion of people fromthe arms of a study can all bias results, typically leading to over-estimation of treatmenteffects. Randomization by a third party prevents the allocation of patients to treatment beingconsciously or subconsciously skewed. It reduces the risk that systematic differencesbetween patients at baseline (i.e., confounders) will bias the result. In large trials,measurable prognostic variables are equally distributed between groups by chance.However, in small trials (e.g., less than 200 patients) minimization can be used as further“insurance policy”. Here the randomization of new patients is weighted according to howpre-specified prognostic variables have distributed themselves in previous patients (MRC,2003). This maximizes the chance that these factors will be equally distributed, whilemaintaining an element of randomization and the concealment of allocation necessary toensure that unmeasured, but often equally biasing factors are not systematically skewed(MRC, 2003).A report of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) should convey to the reader, in a transparentmanner, why the study was undertaken and how it was conducted and analyzed (Moher,Schulz, & Altman, 2001). Despite several decades of educational efforts, RCTs still are notbeing reported adequately (Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001). Inadequate reporting makes theinterpretation of RCT results difficult if not impossible. In response to this, in the mid-1990s,two independent initiatives to improve the quality of reports of RCTs led to the publication ofthe CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001).CONSORT encourages transparency with reporting of the methods and results so that reportsof RCTs can be interpreted both readily and accurately. The use of CONSORT seems toreduce inadequate reporting of RCTs and positively influence the manner in which RCTs areconducted (Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001).All other clinical trials described below may or may not use the process of randomization.Revised March 2006Page 4 of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?3.2 PRECLINICAL TRIALSPreclinical trials are those trials concerned with toxicity testing, pharmacokinetics orpharmacodynamics work (PK-PD), bioassays, determination of a dose that is both effectiveand safe, and bioequivalence studies. All these types of designs occur prior to a drug beingadministered to patients in a routine manner (White, Ashby, & Brown, 2000).To prove that the compound works as is hypothesized and does not reproduce any negativeside-effects, it is first thoroughly tested in animals (i.e., mice, rats, dogs, and monkeys). Thepurpose of this stage is to prove that the drug is not carcinogenic, and to understand how thedrug is absorbed and excreted. Once a pharmaceutical company proves that the compoundappears to be safe, and possibly effective in animals, the company will provide thisinformation to the appropriate authority (Food and Drug Administration; FDA in the U.S. andHealth Canada in Canada), requesting approval to begin testing the compound (experimentaldrug) in humans.Scientific papers that use preclinical study designs may not be directly relevant to healthtechnology assessment, but are certainly building blocks towards it (White, Ashby, & Brown,2000). The drugs and treatments that successfully pass this stage in these studies thenbecome the health technologies to be assessed in routine use (White, Ashby, & Brown,2000).3.3 CROSSOVER TRIALSCrossover trials are often used to assess the effectiveness of a new drug when the diseasebeing studied is chronic and its symptoms can be adequately controlled by medication butworsen when medication is withdrawn. It is a method of comparing two or more treatmentsor interventions in which subjects or patients, on completion of the course of one treatment,are switched to another. Typically, allocation to the first treatment is by random process.Participants’ performance in one period is used to judge their performance in others, usuallyreducing variability (www.research-nurses.com/methodology terminology.html. Thiscrossover is done to address ethical concerns about depriving one group of a possiblybeneficial treatment for the duration of the trial. Crossover trial designs encourage trialparticipation by promising all participants access to the experimental treatment (Quest,2001).One of the advantages of this design is that a smaller sample size is required; the withinsubject variability is minimized by the subjects acting as their own control (White, Ashby, &Brown, 2000).Revised March 2006Page 5 of 32

MODULE 4: How to Assess Clinical Trials (in Surgery)?3.4 MULTI-CENTERE AND INTERNATIONAL CLINICAL TRIALSA clinical trial that is conducted at more than one medical center or clinic is considered amulti-center research trial. Most large clinical trials are conducted at several clinical researchcenters. The benefits of multi-center trials include a larger number of participants, differentgeographic locations, various ethnic groups, the ability to compare results among centers,and thus increased generalizability of the study ter clinical trials are now commonplace, and reflect not only the need for increasednumbers of research subjects but also the multidisciplinary nature of contemporary humanresearch. Harmonization of ethical standards around the world is important given that we arein an environment of international research and medicine. The increasing number ofinternational multi-center trials demands a uniformly high ethical standard for the conduct ofresearch as does the ever-increasing technology and innovation in clinical practice (Tuffin &Chalmers, 1998).3.5 EQUIVALENCE TRIALSThe aim of an equivalence trial is to show the therapeutic equivalence of two treatments,usually a new drug u

therapies and diagnostic tests (American Medical Association, 1992). Much of the statistical literature on study designs that relate to health technology assessment comes from clinical trials; there are relatively few publications that cover the more complex experimental designs, meta-analysis or studies of dr

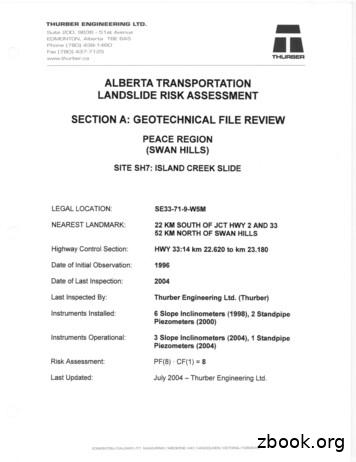

EDMONTON, Alberta TOE 6A5 Phone (780) 438-1460 Fax (780) 437-7125 www.thurber.ca ALBERTA TRANSPORTATION LANDSLIDE RISK ASSESSMENT MR THURBER . Alberta (83-0)." 5. Alberta Research Council, 1976. "Bedrock Topography of the Lesser Slave Lake Map Area, NTS 83 0, Alberta." 6. University and Government of Alberta, 1969. "Atlas of Alberta."

Alberta Native Friendship Centres Association . School of Public Health, University of Alberta Ever Active Schools Kainai Board of Education Alberta Health Services Alberta Recreation and Parks Association Nature Alberta Future Leaders Program, Alberta Sport, Recreation, . and gaming. It is through these opportunities that education occurs.

Alberta Interpretation Act Timelines outlined within the Bylaw shall be complied with pursuant to the Alberta Interpretation Act, as amended, Alberta Building Code In the case where this bylaw conflicts with the Alberta Building Code, the Alberta Building Code shall prevail, Alberta Land Titles

ALBERTA Philip Lee 1 and Cheryl Smyth 2 1 Forest Resources Business Unit, Alberta Research Council, Vegreville, Alberta Canada T9C 1T4. Present address: Senior Research Associate, Integrated Landscape Management Program, Department of Biological Sciences, Biological Sciences Building, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E9.

1 Alberta Research Council, P.O. Bag 4000, Vegreville, Alberta T9C 1T4 2 Present address: Alberta Conservation Association, 6th Floor, Great West Life Building, 9920-108 Street, Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2M4 3 Alberta Conservation Association, Northwest Business Unit, Bag 9000,

6 Government of Alberta Report Back: Addiction and Mental Health Stakeholder Meetings Appendix - List of Attendees Edmonton (August 8, 2018) - 53 attendees in total Metis Indian Town Alcohol Association Alberta Education - Indigenous Mental Health Alberta Community Council on HIV Office of Alberta Health Advocates (2 attendees)

Swan Hills, the Viking in east-central Alberta and at Red Water north of Edmonton, in the Pemiscot at Princess in southern Alberta, and at Judy Creek in northwestern Alberta. Additionally, emerging plays include the Alberta Bakken in the southern reaches of the provin

Alberta Education Cataloguing in Publication Data Alberta. Alberta Education. Focusing on success : teaching students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, grades 1-12. ISBN -7785-5166- 1. Attention-deficit-disordered children - Education - Alberta. 2. Hyperactive children - Education - Alberta. 3.