Alternative Male Mating Tactics In Garter Snakes .

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2005, 70, ive male mating tactics in garter snakes,Thamnophis sirtalis parietalisRI CH AR D SH IN E*, T RAC Y L AN GK ILDE*, M IC HA EL WALL * & ROBERT T. MASON †*School of Biological Sciences A08, University of SydneyyDepartment of Zoology, Oregon State University(Received 21 July 2004; initial acceptance 28 September 2004;final acceptance 10 November 2004; published online 23 May 2005; MS. number: 8211)Alternative mating strategies occur in many animal lineages, often because males adopt tactics best suitedto their own phenotypes or to spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the distribution of females. Garter snakesnear a communal overwintering den in Manitoba show courtship in two contexts: competition from rivalmales is intense close to the den, but weak or absent when males court solitary dispersing females in thesurrounding woodland. Larger size enhances male mating success near the den, but not mate location ratesin the woodland. As predicted by the hypothesis that males match their tactics to their competitiveabilities, our mark–recapture data show that larger, heavier individuals remained near the den, whereassmaller and more emaciated males moved to the woodland. To locate mates, woodland males relied uponsubstrate-deposited pheromonal trails and visual cues (rapid movement), whereas males in the crowdedden environment ignored such cues and instead tongue-flicked every snake they encountered to check forsex pheromones. In arena trials, den males adjusted their courtship intensity to the presence of rival males,whereas woodland males did not (perhaps reflecting the lower probability of interruption by a rival). Thus,male garter snakes adjust the times, places, form and intensity of their reproductive behaviours (matesearching tactics, intensity of courtship) relative to both their own competitive abilities and spatialheterogeneity in mating opportunities.Ó 2005 The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.Although the broad outlines of male reproductive behaviours such as mate searching, courtship and copulation arerelatively invariant within a species, individual malesnone the less differ substantially in the form, intensityand effectiveness with which those behaviours are manifested (Gross 1996). Part of that variation may be nonadaptive, perhaps reflecting individual variation ingenetics, health or vigour. However, a significant proportion of variation in the reproductive behaviour ofmales within a population may represent adaptive matching between an individual’s mating ‘tactics’ and twofactors: (1) the male’s own phenotype (especially hisability to outcompete his rivals) and (2) spatiotemporalheterogeneity in factors such as the availability of females,the ease with which they can be located, and the intensityof competition from rival males. Although links betweena male’s behavioural tactics and other aspects of hisCorrespondence: R. Shine, School of Biological Sciences A08, Universityof Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia (email: rics@bio.usyd.edu.au). R. T. Mason is at the Department of Zoology, Oregon StateUniversity, Cordley Hall 3029, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-2914, U.S.A.0003–3472/05/ 30.00/0phenotype are genetically determined in some taxa (i.e.the population contains multiple genetically distinctmorphs), this situation evolves only under relativelyrestricted conditions (Lank et al. 1995; Zamudio & Sinervo2003). More commonly, alternative male tactics reflectflexibility by individual males, often reflecting differencesin body size and thus competitive ability (Hazel et al.1990; Gross 1996; Immler et al. 2004).Matching phenotype to mating tactics is a simple andintuitive idea. For example, a male that is too small to winphysical battles with larger conspecifics may benefit fromavoiding such battles, focusing instead on alternativetactics such as ‘sneaking’ whereby mating success dependsupon characteristics other than prowess in battle (Andersson 1994; Moczek & Emlen 2000; Bro-Jorgensen &Durant 2003). Similarly, a male that is unable to attracta female successfully may benefit by intercepting her asshe approaches a larger male, or by attempting to inseminate her forcibly. The scientific literature on alternative mating tactics in males includes many examples ofsuch status-dependent shifts, whereby smaller males act as‘satellites’ to intercept females approaching larger males(Brockmann 2002; Eggert & Guyetant 2003; Immler et al.387Ó 2005 The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

388ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 70, 22004; Sato et al. 2004), or wait until larger rivals leavebefore courting the female (Cade 1979; Dominey 1984;Howard 1984; Gross 1996).A second reason for males to be flexible in their matingtactics is in response to heterogeneity (in both time andspace) of the mating opportunities available, and thetactics that would maximize such opportunities. Femalesof different body sizes and reproductive condition will bedistributed in a highly nonrandom fashion, such thatadjacent habitats or time periods may favour very different male tactics (e.g. remain at one site and defend itversus move about widely to find unaccompanied females:Luiselli 1995). Thus, variation in male mating tactics canarise from spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the availabilityand location of females, as well as the specific phenotypictraits of the males themselves. Optimality models predictthat male reproductive behaviours should be flexible inresponse to this heterogeneity, with males adoptingmating tactics best suited to their own phenotypes (e.g.competitive abilities) as well as to the precise matingopportunities afforded by local conditions (Brown &Weatherhead 1999; Thomas 2002). One of the mostcritical factors may be the operational sex ratio (the ratioof fertilizable females to reproductive males). For example,large male European bitterling, Rhodeus sericeus, defendterritories and are aggressive towards conspecifics underequal sex ratios, but shift to participating in multimalespawning aggregations at higher male densities (Mills &Reynolds 2003). Similar flexibility is widespread in othertaxa also (e.g. Gross 1996; Immler et al. 2004).Among reptiles, alternative male mating tactics haveprimarily been studied in lizards (Sinervo & Lively 1996;Whiting 1999; Sinervo et al. 2000; Sinervo 2001; Calsbeeket al. 2002). Most of these cases have focused on territorialmating systems in which physical battles provide a strongadvantage to larger body size in males (Zamudio & Sinervo2003). In such a system, smaller males allocate theirreproductive effort in times and places where competitionfrom their larger rivals is minimized (Zamudio & Sinervo2003). Alternative male mating tactics in lizards ofteninvolve visual (coloured) ‘badges’ that indicate maletactics and status (Hews & Quinn 2003; Whiting et al.2003). In contrast, defence of territories is virtually unknown among snakes (Greene 1997), and snake socialityis oriented around chemoreception rather than vision(Cooper & Greenberg 1992). Perhaps in consequence,alternative male mating tactics have been described onlyrarely in snakes. The most ‘lizard-like’ example of alternative mating tactics in snakes comes from ontogenetic(size-related) shifts in male tactics in the European adder,Vipera berus (Madsen et al. 1993). Males fight with eachother for dominance, larger males win fights, and smallermales adopt cryptic tactics whereby they wait neara female until the larger males have departed (Madsenet al. 1993). Plausibly, however, alternative male matingtactics might evolve even in systems that lack direct male–male combat; for example, subsets of males might differ inthe times and places where they court, or in the kinds(sizes?) of females that they court. Indeed, an example ofthe latter phenomenon has been reported from springaggregations of garter snakes on the Canadian prairies;although males do not engage in any overt battles,alternative male mating tactics co-occur within the denpopulation based on body size. Courtship (and thusmating) is size assortative, with a male’s body size determining his response to pheromonal cues from smallversus large females (LeMaster & Mason 2002; Shine et al.2003). Thus, small males court and mate small as well aslarge females within this system, whereas large malesfocus their efforts on large females (Shine et al. 2001b,2003).We exploited the unique logistical advantages of thegarter snake dens to explore male mating tactics in moredetail, and to see whether there is diversity in male tacticson a spatial as well as ontogenetic scale. In particular, wefocused upon a surprising result from an earlier radiotelemetry study (Shine et al. 2001a). Although manycourting snakes can be seen near the den, much of thecourtship and mating actually occur after the snakes havedispersed into the surrounding woodland (Shine et al.2001a). Because snake densities are dramatically loweroutside the den, these woodland groups are much smallerand male–male competition is less intense (Shine et al.2001a). Does this different context for courtship favourdivergence in male tactics? Both descriptive and manipulative studies have shown that a male garter snake’s abilityto obtain a mating within a courting ‘ball’ depends uponhis body size, his body condition (mass relative to length)and his agility (Shine et al. 2000f, 2004a). In contrast,mate-locating ability is unrelated to male body size (Shineet al. 2005a). Thus, we might expect that larger, heavier,more agile males would stay near the den and compete inlarge courting groups, whereas smaller, thinner, slowermales would move to the surrounding woodland andsearch for unaccompanied females. The much lowerdensities of unmated females in the woodland than theden might also favour divergence in male mate locationmodalities and mating tactics. We set out to test thesepredictions.METHODSStudy Species and AreaSouth-central Manitoba, in the Canadian prairies, isclose to the northern limit of the geographical range ofred-sided garter snakes (Rossman et al. 1996). These small(males average 45 cm snout–vent length [SVL], females55 cm), nonvenomous colubrid snakes gather in largeaggregations at suitable den sites each autumn, and spend8 months inactive underground (Gregory 1974; Gregory &Stewart 1975). The snakes court and mate in early spring,immediately after emerging from the den, before dispersing up to 18 km to their summer ranges (Gregory 1974;Gregory & Stewart 1975). Extensive studies in the Chatfield area north of Winnipeg have documented manyaspects of the physiology, communication systems andbehavioural ecology of these snakes (e.g. Mason 1993;Shine et al. 2000b; LeMaster et al. 2001; LeMaster &Mason 2002, 2003). This work has revealed intense sexualconflict: for example, males obtain matings by inducing

SHINE ET AL.: MATING TACTICS IN MALE SNAKESfemale cloacal gaping via a hypoxic stress response ratherthan (as previously assumed) by stimulating female sexualreceptivity, and females actively avoid male scent (Shineet al. 2004b). Thus, male ‘courtship’ in this system mightless euphemistically be termed ‘attempts at forcible insemination’.The present study was based at a large den 1.5 km northof the town of Inwood (50 31.580 N, 97 29.710 W). Themain den lies in an open rocky area beside a limestonequarry; the snakes emerge from between the rocks. Thesurrounding area is dominated by aspen woodland,extending to within 5 m of the den. During the springemergence period, courting groups of snakes can be foundboth within the den itself, and up to 200 m away throughthe woodland (Shine et al. 2001a). We worked at theInwood den from 5 to 22 May 2003 and 9 to 21 May 2004,encompassing most of the snake’s emergence period ineach of those years.Substrate and Body TemperaturesBecause locomotor performance in snakes is highlysensitive to body temperature (e.g. Greene 1997), anydifference in behaviours between males in two sites mightbe secondary consequences of location-specific differencesin body temperature rather than a genuine divergence inmale ‘tactics’. To address this issue, we collected 25 malesand 25 females in the open, rocky den itself and another25 males and 25 females in the surrounding aspenwoodland. We immediately took their cloacal temperatures with an electronic thermometer, as well as thesurface temperatures of the sites at which they had firstbeen seen.Sampling and Mark–Recapture StudiesIn May 2003 we patrolled the den each day to collectnewly emerged snakes (i.e. those on their first day outafter their 8-month winter inactivity). Females dispersesoon after emergence, and attract intense courtship(Whittier et al. 1985); thus, newly emerged females wereeasy to locate. Newly emerged males also attract courtshipby other males for the first day postemergence (Shine et al.2000c) and thus surveys for courted snakes were effectivein locating recent emergers of both sexes. We measured(SVL) and weighed all of these snakes, gave each anindividual painted number on the dorsal surface, thenreleased them in the den the same day (or rarely, thefollowing day). The nontoxic paint marks were generallyreadable for about 2 weeks, so that recaptures of theseanimals provided data on correlates of emergence, movements and philopatry (see below).To sample snakes that concentrated their mate-searching activities away from the den, as well as to capturedispersing animals, in May 2003 we set up a 60-m driftfence of wire mesh (‘hardware cloth’) 20 cm high, with sixevenly spaced funnel traps on either side of the fence. Thedrift fence was erected in aspen woodland 100 m from themain Inwood den, oriented to catch snakes dispersingaway from (or towards) the den. Traps were checked andcleared twice daily (or more often when capture rateswere high), yielding data on 6653 animals. All snakes weretaken back to the field laboratory where they weremeasured before release the following morning. For thefirst 4 days of the study, we paint-marked each trappedsnake to record in which trap it had been caught; theseanimals were then released back at the den to see if theywould disperse in the same direction a second time. Onsubsequent days the trapped snakes were not marked, butsimply measured and released on the opposite side of thefence.Courting in Woodland versus the DenRadiotelemetry has shown that some courting malesnakes remain near the den, some disperse and court inthe woodland, and others move back and forth betweenthese two areas (Shine et al. 2001a). If the number ofsnakes in the two former categories outnumber those inthe latter category, then it should be possible to identifyindividual males as belonging to either a ‘den’ or ‘woodland’ assemblage. That is, do individual male garter snakestypically focus their efforts on courting in either the den orthe woodland, rather than both? If so, we should be able todetect the existence of a ‘woodland’ group by examining(1) philopatry: some of the paint-marked snakes (seeabove) should be consistently recaptured at the drift fencerather than at the den; (2) homing: if we displace snakes,they should return to the drift fence, and perhaps to a siteclose to where they were originally captured.Reproductive ActivitiesTo quantify differences in reproductive activities in theden versus the woodland, we surveyed both areas. Werecorded the numbers of males in each courting group,and whether or not the females had already mated (asevidenced by a large gelatinous mating plug, whichpersists for O2 days: Shine et al. 2000e). To quantify theintensity of competition from rival males, we set upstandardized trials in both habitat types to characterizethe rates at which males were able to locate females, andthe cues by which they accomplished that task. To do thiswe anaesthetized eight unmated females (by intramuscular injection of 5 mg/kg brietal sodium). These animalswere quiescent for 25–35 min after injection, and allrecovered completely (and were then released) within60 min; no adverse effects of anaesthesia were apparent.Each anaesthetized female was dragged ventral surfacedownwards for 5 m to deposit a pheromonal trail, andthen laid out at the end of her trail. Adjacent females andtheir trails were separated by at least 5 m. We scored thetime taken for males to arrive and begin courting thefemale; each male was removed as soon as he commencedcourtship. We also scored whether each male found thefemale by following her substrate-deposited pheromonaltrail (evident because of frequent side-to-side head movements and tongue flicking to the substrate: Ford & Schofield 1984) or more simply, by tongue flicking other snakesas they were encountered. Trials were terminated after389

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 70, 2arrival of the 10th male, or after 15 min (whichever wassoonest).To clarify further the cues used by mate-searching malesin the two habitat types, we used a 1.2-m length of nylonrope, attached to a stick so that rapid vibration of thehandle caused the rope to whip about at ground level ina sinuous fashion, to mimic the movement patternscharacteristic of vigorously courted snakes. The rope waswriggled about for 10 s, 30 cm in front of the head ofa solitary (and presumably mate-searching) male either inthe den or in a grassy clearing in the surroundingwoodland. We scored the focal male’s response (approach,retreat or ignore) over the following 30 s.Focal Sampling of Male BehaviourAn observer (R.S.) walked through both the den and thewoodland. He randomly selected a male snake and thenrecorded its behaviour for the next 60 s. The behavioursrecorded were: distance travelled; total straight-line displacement; number of other snakes tongue-flicked; number of rival males within a courting group; and theproportion of the 60-s period spent courting, trail following(tongue flicking the substrate) and ‘periscoping’ (head andneck raised well above the substrate).Ethical NoteResearch was conducted under the authority of OregonState University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All research was conducted in accord with the U.S.Public Health Service ‘Policy on Humane Care and Use ofLaboratory Animals’ and the National Institutes of Health‘Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’.RESULTSSubstrate and Body TemperaturesSubstrate temperatures at places where snakes werefound were similar in the den and the surroundingwoodland (two-factor ANOVA; main effect of location:F1,96 Z 1.26, P Z 0.26), but males were generally oncooler substrates than were females (F1,96 Z 18.83,P ! 0.0001), with no significant interaction betweenthese factors (F1,96 Z 0.02, P Z 0.88; Fig. 1a).Patterns were different for cloacal temperatures,however; males and females had similar mean body30(a)FemaleMale25Facultative Responses to CompetitionIntensityAny differences between males in the woodland versusthe den in the intensity of courtship might be caused byintrinsic differences between the males, or facultativeresponses to factors that differed between the two areas(e.g. number of rival males in courting groups). To teaseapart these possibilities, we erected 24 open-topped nylonarenas (1 ! 1 ! 0.8 m) in a grassy area near the den, andadded either one or 20 male snakes to each arena. In halfof the arenas, these males came from the den; in the otherhalf, the males were taken from the drift fence. Thisdesign thus generated four treatments: den or woodlandmales, either by themselves or with 19 other males. In allarenas, a single male was randomly identified as the focalanimal, and paint-marked for easy recognition. We thenadded a single unmated female (recently collected fromthe den) to each arena, and recorded the intensity ofcourtship by the focal male at 5-min intervals for the next30 min. Courtship intensity was scored as the number ofobservation periods (out of a total of five) during whichthe focal male was aligned with,

iours such as mate searching, courtship and copulation are relatively invariant within a species, individual males none the less differ substantially in the form, intensity and effectiveness with which those behaviours are man-ifested (Gross 1996). Part of that variation may be non-adaptive, perhaps reflecting individual variation in

bsp sae bsp jic bsp metric bsp metric bsp uno bsp bsp as - bspt male x sae male aj - bspt male x jic female swivel am - bspt male x metric male aml - bspt male x metric male dkol light series an - bspt male x uno male bb - bspp male x bspp male bb-ext - bspp male x bspp male long connector page 9 page 10 page 10 page 11 page 11 page 12 page 12

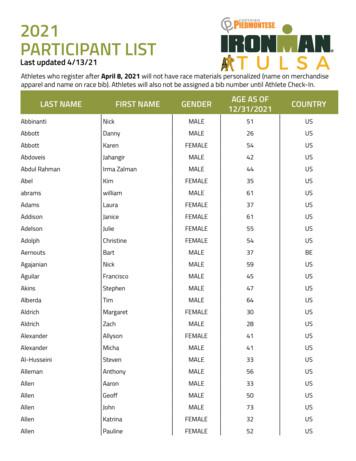

Apr 13, 2021 · Berry Dave MALE 43 US Berry Philip MALE 38 US Berry Will MALE 48 US Bertelli Scott MALE 29 US Besel DJ MALE 45 US Beskar Daniel MALE 49 US Beurling John MALE 59 CA Bevenue Chris MALE 51 US Bevil Shelley FEMALE 56 US Beza Jose-Giovani MALE 52 US Biba Frazier MALE 33 US Biehl Chad MALE 47 US BIGLER ASHLEY FEMALE 39 US Bilby Steven MALE 45 US

Figure 4.15 Cross-section taken for 1D tolerance stack-up analysis consideration 100 Figure 4.16 Vector loop diagram of newly design mating interfaces 101 Figure 4.17 Mating side of (a) male and (b) female mating interfaces 104 Figure 4.18 Orientation of male and female mating interface just before assembly 105

1.1 Using Tactics in Practice 2 2 Tactics for Availability 5 2.1 Updating the Tactics Catalog 6 2.2 Fault Detection Tactics 6 2.3 Fault Recovery Tactics 10 2.4 Fault Prevention Tactics 16 3 An Example 19 3.1 The Availability Model 19 3.2 The Resulting Redundancy Tactic 21 3.3 Tactics Guide Architectural Decisions 22 .

Connector Kit No. 4H .500 Rear Panel Mount Connector Kit No. Cable Center Cable Conductor Dia. Field Replaceable Cable Connectors Super SMA Connector Kits (DC to 27 GHz) SSMA Connector Kits (DC to 36 GHz) Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female 201-516SF 201-512SF 201-508SF 202 .

tactics and discuss the range of tactics identified by research, as well as their effects on various outcomes. Impression management tactics Research has identified a range of IM tactics and has found several ways to classify these tactics. The simplest distinction views IM tactics as either verbal or non-verbal (Schneider, 1981).

ADHOME HVAC MARKETING FUNNEL AWARENESS INTEREST CONSIDERATION INTENT EVALUATION PURCHASE DESCRIPTION MARKETING TACTICS MARKETING TACTICS MARKETING TACTICS MARKETING TACTICS MARKETING TACTICS MARKETING TACTICS DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION Someone in this stage is hearing about your brand for the first time. They .

ANSI/B1.20.1 ISO 7 Size EN 837-1 G ⅛ B, male thread G ¼ B, male thread M10 x 1, male thread ANSI/B1.20.1 ⅛ NPT, male thread ¼ NPT, male thread ISO 7 R ⅛, male thread R ¼, male thread Materials (wetted) Measuring element Copper alloy Process connection with lower measuring flangeCopper alloy