DESIGNING SOCIAL CAPITAL SENSITIVE PARTICIPATION METHODOLOGIES

DESIGNINGS O C I A L C A P I TA LSENSITIVEPA R T I C I PAT I O NMETHODOLOGIESTristan Claridge June 2004

This research was carried out and fully funded by Social CapitalResearch.Social Capital Research20 Allandale RoadSaint Clair, DunedinNew ZealandTel.: 64 (0)22 018 9043Email: earch.comSocial Capital Research 2004 – All rights reserved.Copyright NotificationNo part of this publication may be reproduced or Transmitted inany form or by any means, including Photocopying and recording, or by any information Storage and retrieval system withoutthe prior permission in writing from the proprietor. Copying orreproduction in whole is permitted if the copy is complete andunchanged (including this copyright statement).Social Capital Research declines all responsibility for any errorsand any loss or damage resulting from use of the contents ofthis White Paper.Social Capital Research also declines responsibility for anyinfringement of any third party’s Intellectual Property Rights(IPR), but will be pleased to acknowledge any IPR and correctany infringement of which it is advised.This White Paper is issued for information only. The viewsexpressed are entirely those of the author(s). White Papersdescribe research in progress by the author(s) and are publishedto elicit comments and further debate.Design and layout: Meg Claridge

ABSTRACTParticipation methodologies have been evolving and improving sincefirst gaining international recognition in the 1960s. Despite theseimprovements there are stillgenuine concerns and criticisms ofparticipation, particularly surrounding its application and effectiveness.The recent advent of social capital theory provides another lens for theanalysis and ensuing improvement of participationmethodologies. Socialcapital theory encompasses the notion that our social relationships areproductive in nature; that is, ‘capital’. The theory describes the variousdimensions of the complex social world that enable this capital. Bothparticipation and social capital theories have many similarities; bothare poorlydefined, conceptualized and operationalized in both debateand application. The two concepts are highly context specific and highlycomplex. Individually, the concepts still require further analysis to answerkey questions, particularly about appropriate application. Jointly, littlework has been done to identify the impacts that they have on eachother and particularly how social capital benefits can be maximized inparticipatory methodologies.This study explored the theories with extensive literature reviews ofeach concept before breaking new ground with an integration of thetwo theories. This synthesis was then applied to a case study; an IFADfunded project in Zimbabwe. The project’s participatory methodologywas analysed through the lens of social capital theory. The participatorymethods analysed included; focus groups, public meetings,informationdissemination and questionnaires. The analysis highlighted the potentialimportance of social capital sensitive participatory methodologies.Despite the efforts of the project development team, there werenumerous oversights or missed opportunities where the project andcommunity could have benefited from variations to the methodologyused. It was found that by providing opportunities for repeat interactionin the participatory methodologies, social capital benefits couldbe maximised. It was also stressed that any social capital sensitiveparticipatory methodology is by definition local context specific andapplication of such methods require careful analysis of the local contextin which it is being applied.

TABLE OF CONTENTSABSTRACT3TABLE OF CONTENTS4LIST OF FIGURES, DIAGRAMS51.0 INTRODUCTION62.0 METHODOLOGY63.0 LITERATURE REVIEW73.1 SOCIAL CAPITAL THEORY73.1.1 Evolution of Social Capital Theory73.1.2 Contemporary Authors on Social Capital73.1.3 Definition of Social Capital83.1.4 Capital Debate93.1.5 Theory93.1.6 Conceptualisation123.1.7 Operationalisation15163.1.8 Gender Issues3.1.9 Social Capital Literature Review Summary163.2 PARTICIPATION THEORY173.2.1 Evolution of Participation Theory173.2.2 Definition of Participation183.2.3 Community in Participation213.2.4 Empowerment213.2.5 Popularity pervasiveness of Participation223.2.6 Application and Misuse of Participation233.2.7 Participation as an End or Means253.2.8 Typologies253.2.9 Importance of Participation263.2.10 Limitations of Participation273.2.11 Gender Issues and Participation283.2.12 Participation Theory Literature Review Summary28

4.0 CASE STUDY OVERVIEW295.0 DISCUSSION305.1 INTEGRATION OF PARTICIPATION AND SOCIAL CAPITAL THEORIES305.2 CASE STUDY FINDINGS335.2.1 Focus Groups335.2.2 Public Meetings355.2.3 Dissemination of Information365.2.4 Questionnaires376.0 RECOMMENDATIONS377.0 CONCLUSIONS408.0 REFERENCES40LIST OF FIGURES, DIAGRAMSFigure 1. Illustration of the interaction of levels atFigure 2. Conceptualization of social capital developed by Grootaert and Van Bastelaer (2002)Figure 3. Conceptual Framework: Levels and Types of Social CapitalFigure 4. Conceptualization of social capital simplifying the complexity of the social worldinto a diagram outlining relationships between determinants, structure (or elements) andconsequences.Table 1. Four views of social capital (Source: Woolcock and Narayan 2000)

1.0 INTRODUCTIONParticipation methodologies have beenevolving and improving since first gaininginternational recognition in the 1960s. Despitethese improvements there are still genuineconcerns and criticisms of participation,particularly surrounding its application andeffectiveness. The recent advent of socialcapital theory provides another lens forthe analysis and ensuing improvement ofparticipation methodologies. Social capitaltheory encompasses the notion that oursocial relationships are productive innature; that is, ‘capital’. The theory describesthe various dimensions of the complexsocial world that enable this capital. Bothparticipation and social capital theories havemany similarities; both are poorly defined,conceptualized and operationalized in bothdebate and application. The two concepts arehighly context specific and highly complex.Individually, the concepts still require furtheranalysis to answer key questions, particularlyabout appropriate application. Jointly, littlework has been done to identify the impactsthat they have on each other and particularlyhow social capital benefits can be maximizedin participatory methodologies.This study explores the theories with extensiveliterature reviews of each concept beforebreaking new ground with an integrationof the two theories. This synthesis is thenapplied to a case study; an IFAD funded projectin Zimbabwe. The project’s participatorymethodology are analysed through the lensof social capital theory. The participatorymethods analysed included; focus groups,public meetings, information disseminationand questionnaires. The analysis highlightsthe potential importance of social capitalsensitive participatory methodologies.The first section outlines the methodologythis study follows before an overview of thecase study. The discussion section firstlyD E S I G N I N G S O C I A L C A P I TA L S E N S I T I V EPA R T I C I PAT I O N M E T H O D O L O G I E Sincludes an integration of social capital andparticipation theories before applying thisintegration to the case study participatorymethodologies. The case study discussionis split into 4 sections: focus groups, publicmeetings, information dissemination andquestionnaires. The final section includesa long description of the recommendationscoming from the case study findings beforeidentifying the overall conclusions of thestudy.2.0 METHODOLOGYPrimary data analysis was ruled out as anoption for this study as both participation andsocial capital are abstract in nature and do notlend themselves to meaningful or rigorousquantitative or qualitative measurement.Secondary data analysis was thereforeused and a rigorous method of literatureidentification and review was undertaken.Databases were selected from a range ofdisciplines including sociology, economics,political science and anthropology. Theextensive literature reviews provided a soundplatform for further exploring the integrationof social capital and participation theoriesand for application to the case study. As bothconcepts are complex and poorly defined andconceptualized in the literature, this studyfirstly, will review literature on each conceptto gain a more thorough understanding ofthe concepts. These literature reviews willdraw out questions that will be explored inthe discussion chapter that will synthesis theliterature and apply it to a case study.A case study approach provides an opportunityto apply the literature on the concepts toreal situations. For the purposes of thisstudy, a case study in a developing countrycontext was selected and findings from thiscase study were applied to the developedcountry context. A suitable case study waschosen that includes clear participatory6

methodologies and identification of theiroutcomes, appropriate for the illustration ofthe findings of the literature review synthesis.Chapter 4 outlines the details of the casestudy situation.3.0 LITERATURE REVIEW3.1 SOCIAL CAPITAL THEORY3.1.1 EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL CAPITAL THEORYSocial capital’s intellectual history has deepand diverse roots which can be traced to theeighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Adamand Roncevic 2003). The idea is connectedwith thinkers such as Tocqueville, J.S. Mill,Toennies, Durkheim, Weber, Locke, Rousseauand Simmel (Bankston and Zhou 2002;Brewer 2003; Lazega and Pattison 2001; Portesand Sensenbrenner 1993; Putnam 1995). Theterm explains a commonly used adage: ‘it’snot what you know, it’s who you know’, andthus the concept is not new, but the termhas only been coined fairly recently (Labonte1999; Lazega and Pattison 2001; Portes andSensenbrenner 1993; Putnam 1995).The first use of the term has been tracedto Hanifan in 1916 however others haveidentified Jacobs (1961) (Felkins 2002),Loury (1977) (Lappe et al. 1997; Leeder andDominello 1999), and the Royal Commissionon Canada’s Economic Prospects (Schulleret al. 2000). Routledge and Amsberg (2003)identified that Hanifan used the term ‘capital’specifically to highlight the importance of thesocial structure to people with a businessand economics perspective. It was not untilthe early 1990s that the concept gainedwidespread recognition with the writings ofBourdieu (1986), Coleman (1988) and Putnam(1993), who are considered the contemporaryauthors on social capital.D E S I G N I N G S O C I A L C A P I TA L S E N S I T I V EPA R T I C I PAT I O N M E T H O D O L O G I E S3.1.2 CONTEMPORARY AUTHORS ON SOCIALCAPITALThe contemporary authors commonly citedare Pieere Bourdieu, James Coleman andRobert Putnam (Carroll and Stanfield 2003;Lang and Hornburg 1998). Adam and Roncevic(2003) cite the release of his well-knownbook Distinction published in French in 1979as the origination of the modern notion ofsocial capital. Bourdieu’s definition of socialcapital could be described as ‘egocentric’ asit is considered in the broader framework ofsymbolic capital and of critical theories ofclass societies (Wall et al. 1998). Bourdieudefines social capital as‘the aggregate of the actual or potentialresources which are linked to possessionof a durable network of more or lessinstitutionalized relationships of mutualacquaintance and recognition – or inother words, to membership in a group –which provides each of its members withthe backing of the collectivity-ownedcapital, a ‘credential’ which entitles themto credit, in the various senses of theword’ (Bourdieu 1986, web page).James Coleman, a sociologist with strongconnections to economics through rationalchoice theory (Jackman and Miller 1998; Li etal. 2003; Schuller et al. 2000), draws togetherinsights from both sociology and economicsin his definition of social capital:‘Social capital is defined by its function. It isnot a single entity, but a variety of differententities having two characteristics incommon: they all consist of some aspectof social structures, and they facilitatecertain actions of actors – whetherpersons or corporate actors – within thestructure’ (Coleman 1988, p. S98).Coleman’s work represents an importantshift from Bourdieu’s individual outcomes7

(as well as in network-based approaches)to outcomes for groups, organizations,institutions or societies which represents atentative shift from egocentric to sociocentric(refer to table 1) (Adam and Roncevic 2003;Cusack 1999; McClenaghan 2000). Colemanextended the scope of the concept fromBourdieu’s analysis of the elite to encompassthe social relationships of non-elite groups(Schuller et al. 2000).Robert Putnam, a political scientist wasresponsible for popularizing the conceptof social capital through the study of civicengagement in Italy (Boggs 2001; Schuller etal. 2000). In Making Democracy Work (Putnamet al. 1993) the authors explore the differencesbetween regional governance in the north andsouth of Italy, the explanatory variable beingcivic community. The next of Putnam’s workfocused on the decline in civic engagementin the United States (Schuller et al. 2000). LikeColeman, Putnam was extensively involvedin empirical research and formulation ofindicators and was responsible for thedevelopment of the widely applied measureso-called ‘Putnam instrument’ (Adam andRoncevic 2003; Paldam and Svendsen 2000).Putnam’s arguments have been criticized ascircular and tautological – simultaneously acause and effect (Pope 2003; Portes 1998).The current works on social capital representearly attempts to identify and conceptualizethis complex theory. Grootaert and VanBastelaer (2002a) suggested that the socialcapital model may currently be at the sameearly stage that human capital theory wasthirty or forty years ago. By the late 1990s thenumber of studies of social capital increasedsignificantly. It could be generalized thatmuch of this work lacked rigor and did nottake into account the multi-dimensionalnature of social capital. Much of the work waspiece-meal in nature, simply applying anapproach to a discipline or area of interest.The role of Putnam’s research in thisD E S I G N I N G S O C I A L C A P I TA L S E N S I T I V EPA R T I C I PAT I O N M E T H O D O L O G I E Sprocess was significant. Putnam’s work, whilepopularizing the concept, led to a significantweakening of the conceptualization andoperationalization of the concept. Coleman’searlier work provided a more ization. Putnam however, applieda single proxy analysis of social capital andapplied it to good governance. Seen as theforemost expert on social capital at the time,many authors followed in his footsteps, andPutnam’s lack of rigor was replicated in piecemeal works across a variety of disciplines(Claridge, 2004). Putnam is not solely to blamefor this situation, which is due mostly to thecomplexity and attractiveness of the conceptof social capital. The result was a plethoraof definitions and operationalization of theconcept that led to the theory itself beingquestioned. From this work many recentauthors have synthesized a more rigorousframework for the conceptualization andoperationalization of the concept, but muchwork is left to be done if social capital theoryis to provide a meaningful contribution in allits facets.3.1.3 DEFINITION OF SOCIAL CAPITALThe commonalities of most definitions ofsocial capital are that they focus on socialrelations that have productive benefits.The variety of definitions identified in theliterature stem from the highly context specificnature of social capital and the complexity ofits conceptualization and operationalization.There is no commonly agreed definition ofsocial capital and the definition adoptedby any given study seems to depend on thediscipline and level of investigation (Robisonet al. 2002). Social capital is commonlyidentified in terms of discipline, level of studyand context and definitions vary dependingon whether they focus on the substance, thesources, or the effects of social capital (Adlerand Kwon 2002; Field et al. 2000; Robison et8

al. 2002). Adler and Kwon (2002) identifiedthat the core intuition guiding social capitalresearch is that the goodwill that others havetoward us is a valuable resource. As suchthey define social capital as ‘the goodwillavailable to individuals or groups. Its sourcelies in the structure and content of theactor’s social relations. Its effects flow fromthe information, influence, and solidarityit makes available to the actor’ (Adler andKwon 2002, p. 23). Dekker and Uslaner (2001)posited that social capital is fundamentallyabout how people interact with each other.3.1.4 CAPITAL DEBATEThere is considerable controversy in theliterature over the use of the term ‘capital’(Falk and Kilpatrick 1999; Hofferth et al. 1999;Inkeles 2000; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; Schmid2000; Smith and Kulynych 2002). Social capitalis similar to other forms of capital in that itcan be invested with the expectation of futurereturns (Adler and Kwon 1999), is appropriable(Coleman 1988), is convertible (Bourdieu1986), and requires maintenance (Gant et al.2002). Social capital is different from otherforms of capital in that it resides in socialrelationships whereas other forms of capitalcan reside in the individual (Robison et al.2002). Further, social capital cannot be tradedby individuals on an open market like otherforms of capital, but is instead embeddedwithin a group (Gant et al. 2002; Glaeser etal. 2002). It is clear from the literature thatsocial capital has both similarities anddissimilarities with neocapital theories andis certainly quite dissimilar from classicaltheory of capital.Many authors identify that both forms ofsocial capital, structural and cognitive,qualify as capital because they both requiresome investment – of time and effort if notalways of money (Grootaert 2001; Grootaertand Van Bastelaer 2002b; Krishna and UphoffD E S I G N I N G S O C I A L C A P I TA L S E N S I T I V EPA R T I C I PAT I O N M E T H O D O L O G I E S2002). It can be concluded that social capitalis unlike other forms of capital but also notsufficiently dissimilar to warrant a differentterm. Certainly it is the use of the termcapital that makes the concept attractiveto such a wide range of people given thebringing together of sociology and economics(Adam and Roncevic 2003). Perhaps a moreappropriate term may be social solidarity asthe notion connotes relations of trust, cooperation and reciprocity just as much associal capital and might be used in place ofit to overcome the problem identified abovewith using the term capital. It is interestingthat the term capital should be used withsocial, considering capital is already asocial relation. In the original sense of theword capital, an object is only capital underparticular social conditions. In the sameway the sources of social capital are onlycapital under particular social conditions. Forexample, a favor owed is only capital undercertain, not necessarily favorable conditions.This idea brings in the notion of negative orperverse social capital (see negative socialcapital section).3.1.5 THEORYSocial capital theory is incredibly complexwithresearchersandpractitionersapproaching it from various disciplines andbackgrounds for various applications. Theresult is considerable diversity, controversyand disagreement surrounding the theory.This section will discuss the followingcomponents of the theory: dimensions, levels,types, determinants, benefits, and downsides.3.1.5.1 DIMENSIONSSocial capital is multi-dimensional with eachdimension contributing to the meaning of9

social capital although each alone is not ableto capture fully the concept in its entirety(Hean et al. 2003). The main dimensions arecommonly seen as:authors posit social capital at the

participation methodologies. Social capital theory encompasses the notion that our social relationships are productive in nature; that is, ‘capital’. The theory describes the various dimensions of the complex social world that enable this capital. Both participation and social capital theories have many similarities; both are poorly defined,

Capital Program Development and Structure Capital Improvement Program (CIP) Update 10-Year Capital Plan. Identifies viable initiatives to address needs identified for next 10 years; financially unconstrained. Six-Year Capital Improvement Program (CIP) Capital investments planned for, or continuing in, six-year capital program. One-Year Capital .

Next, it addresses regional development and social capital, including core topics such as territorial distribution of social capital, its association with various aspects of regional development. The section also includes related research on social capital in cross-border relations, minority governance, and social capital and local labour markets.

O capital social corresponde à quantia que os proprietários entregam à sociedade e constitui o capital de risco, ou seja, o capital que é necessário para iniciar ou desenvolver determinada atividade. O capital social é uma massa patrimonial que integra o capital próprio e a sua importância prende-se, fundamentalmente,

COVID-19 - Potential implications on Banking and Capital Markets 06 Capital markets Overview of Ghana’s capital market Ghana’s capital market is gradually playing a pivotal role in attracting long-term capital financing for economic activities. The largest capital market i

Figure 2 Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation 11 Figure 3 Pretty’s typology of participation 11 Figure 4 White’s typology of interests 12 Figure 5 Framework for analysing participation 14 Figure 6 Possible applications of the framework 17 Figure 7 Participation

Designing your Tesla Coil September 2003 Rev 2 www.spacecatlighting.com Designing your Tesla Coil Introduction When I was in the process of designing my first tesla coil in May of 2002, I was hardpressed to find one source that comprehensibly described the process of designing a tesla coil from scratch.

Designing FIR Filters with Frequency Selection Designing FIR Filters with Equi-ripples Designing IIR Filters with Discrete Differentiation Designing IIR Filters with Impulse Invariance Designing IIR Filters with the Bilinear Transform Related Analog Filters. Lecture 22: Design of FIR / IIR Filters. Foundations of Digital .

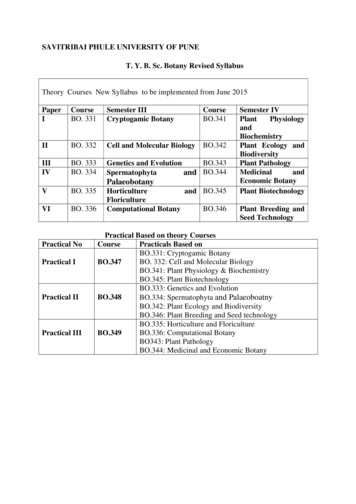

Algae: (11L) 2. Algae: General characters, economic importance and Classification (Chapman and Chapman, 1973) up to classes. 03L . 3. Study of life cycle of algae with reference to taxonomic position, occurrence, thallus structure, and reproduction of Nostoc, Chara, Sargassum and Batrachospermum . 08 L.