Culture And Imperialism

CULTUREANDIMPERIALISMEdward W. SaidVINTAGE BOOKSA Division of Random House, Inc.New York

FffiSTVINTAGE BOOKS EDillON,JUNE 1994Portions of this work, in different versions, have appeared in Field Dty Pamphlets,Grand Street, the Gtumlitm, Lond011 Reuiew ofBoolts, Nr.o Left Rer;iew, Rttrittm, thePenguin edition of Kim, Rme tmd Class, and "lid Wdliams: CritiuJ Persp«tivtt,edited by Terry Eagleton.Grateful acknowledgment is made to Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. and Faber andFaber Ltd., for permission to reprint "Tradition and the Individual nlent" fromSektted & ys by T. S. Eliot, copyright 1950 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.,and tenewed 1978 by Esme Valerie Eliot.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataSaid, Edward W.Culture and imperialism/Edward W. Said- 1st Vintage Booka ed.P· em.Originallypubliohed: New York: Knopf, 1993.Includes bibliogr phical rcti.rences and index.ISBN 0-679-75054-1I. European literature - Hiotory and criticism-Theory, etc.2. Uterarore- Hiororyand criticism-Theory, etc. 3. Imperialism in literature.4. Colonies in literature. 5. Politics and culture.I. Tide.[PN761.S28 1994]809' .894- dc2093-43485CIPManufactured in the United States of America10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 I

ForEqbal Ahmad

The conquest of the eanh, which mostly means the taking it awayfrom those who have a different complexion or slightly flaner nosesthan ourselves, is not a preny thing when you look into it roo much.What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not asentimental pretence but an idea; and an unselfish belief in theidea--something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer asacrifice to.JosEPH CoNRAD, Heart of.Darlmess

ContentsIntroductionxiCHAPTERONEOVERLAPPING TERRITORIES,INTERTWINED HISTORIESIIIllIVvEmpire, Geography, and CultureImages of the Past, Pure and ImpureTwo Visions in Hem of Darkne.tDiscrepant ExperiencesConnecting Empire to Secular Interpretation3IJ193'43CHAPTER TWOCONSOLIDATED VISIONIIIllIVvVIVIIVIIINarrative and Social SpaceJane Austen and EmpireThe Cultural Integrity of EmpireThe Empire at Work: Verdi's AidaThe Pleasures of ImperialismThe Native Under ControlCamus and the French Imperial ExperienceA Note on Modernism618o97Ill131161169J86

ContentsXCHAPTER THREERESISTANCE AND OPPOSITIONIIIIIIVvThere Are Two SidesThemes of Resistance CultureYeats and DecolonizarionThe Voyage In and the Emergence of OppositionCollaboration, Independence, and Liberation1912092202 39262CHAPTER FOURFREEDOM FROM DOMINATION IN THE FUTUREIIIIIAmerican Ascendancy: The Public Space at WarChallenging Orthodoxy and AuthorityMovements and MigrationsNotesIndexz823 3]26

IntroductionAbout five years after Orienta/ism was published in 1978, I began to gathertogether some ideas about the general relationship between cultureand empire that had become clear to me while writing that book. The first·result was a series oflectures that I gave at universities in the United States,Canada, and England in·1985 and 1986. These lectures form the core argument of the present work, which has occupied me steadily since that time.A substantial amount of scholarship in anthropology, history, and areastudies has developed arguments I put forward in OrieniiiJiJm, which waslimited to the Middle East. So I, too, have tried here to expand the arguments of the. earlier book to describe a more general pattern of relationshipsbetween the modern metropolitan West and its overseas territories.What are .some of the non-Middle Eastern materials drawn on here?European writing on Africa, India, parts of the Far East, Australia, and theCaribbean; these Africanist and Indianist discourses, as some of them havebeen called, I see as part of the general European effort to rule distant landsand peoples and, therefore, as related to Orientalist descriptions of theIslamic world, as well as to Europe's special ways of representing theCaribbean islands, Ireland, and the Far East What are striking in thesediscourses are the rhetorical figures one keeps encountering in their descriptions of"the mysterious East," as well as the stereotypes about "the African[or Indian or Irish or Jamaican or Chinese] mind;" the notions about bringing civilization to primitive or barbari peoples, the disturbingly familiarideas about flogging or death or extended punishment being required when"they" misbehaved or became rebellious, because "they" mainly understoodforce· or violerice best; "they" were. not like "us," and for that reason de served to be ruled.

xiiIntroductionYet it was the case nearly everywhere in the non-European world that thecoming of the wl-iite man brought forth some sort of resistance. What I leftout of Orimtalirm was that response to Western dominance which culminated in the great movement of decolonization all across' the ThirdWorld. Along with armed resistance in places as diverse as nineteenthcentury Algeria, Ireland, and Indonesia, there also went considerable effortsin cultural resistance almost everywhere, the assertions of nationalist identities, and, in the political realm, the creation of associations and parties whosecommon goal was self-determination and national independence. Never wasit the case that the imperial encounter pitted an active Western intruderagainst a supine or inert non-Western native; there was ai'Wayr some form ofactive resistance, and in the overwhelming majority of cases, the resistancefinally won out.These two factors-a general world-wide pattern of imperial culture, anda historical experience of resistance against empire--inform this book inways that make it not just a sequel to Orimtalirm but an attempt to dosomething else. In both books I have emphasized what in a rather generalway I have called "culture." As I use the word, "culture" means two thingsin particular. First of all it means all those practices, like the arts of description, communication, and representation, that have relative autonomy fromthe economic, social, and political realms and that often exist in aestheticforms, one of whose principal aims is pleasure. Included, of course, are boththe popular stock of lore about distant parts of the world and specializedknowledge available in such learned disciplines as ethnography, historiography, philology, sociology, and literary history. Since my exclusive focus here s on the modem Western empires of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I have looked especially at cultural forms like the novel, which I believewere immensely important in the formation ofimperial attitudes, references,and experiences. I do not mean that only the novel was important, but thatI consider it the aesthetic object whose connection to the expanding societiesof Britain and France is particularly interesting to study. The prototypicalinodern realistic novel is Robinson Cru.roe, and certainly not accidentally it isabout a European who creates a fiefdom for himself on a distant, nonEuropean island.A great deal of recent criticism has concentrated on narrative fiction, yetvery little attention has been paid to· its position in the history and world ofempire. Readers of this book will quickly discover that narrative is crucialto my argument here, my basic point being that stories are at the heart ofwhat explorers and novelists say about strange regions of the world; theyalso become the method colonized people use to assert their own identityand the existence of their own history. The main battle in imperialism is

IntroductionXlll over land, of course; but when it came to who owned the land, who had theright to settle and work on it, who kept it going, who won it back, and whonow plans its future--these issues were reflected, contested, and even for atime decided in narrative. As one critic has suggested, nations themselvesare narrations. The power to narrate, or to block other narratives fromforming and emerging, is very important to culture and imperialism, andconstitutes one of the main connections between them. Most important, thegrand narratives of emancipation and enlightenment mobilized people in thecolonial world to rise up and throw off imperial subjection; in the process,many Europeans and Americans were also stirred by these stories and theirprotagonists, and they too fought for new narratives of equality and humancommunity.Second, and almost imperceptibly, culture is a concept that includes arefining and elevating element, each society's reservoir of the best that hasbeen known and thought, as Matthew Arnold put it in the 186os. Arnoldbelieved that culture palliates, if it does not altogether neutralize, the ravages of a modern, aggressive, mercantile, and brutalizing urban existence.You read Dante or Shakespeare in order to keep up with the best that wasthought and known, and also to see yourself, your people, society, andtradition in their best lights. In time, culture comes to be associated, oftenaggressively, with the nation or the state; this differentiates ·"us" from"them," almost always with some degree of xenophobia. Culture in thissense is a source of identity, and a rather combative one at that, as we seein recent "returns" to culture and tradition. These "returns" accompanyrigorous codes of intellectual and moral behavior that are opposed to thepermissiveness associated with such relatively liberal philosophies as multiculturalism and hybridity. the formhly colonized world, these "returns"have produced varieties of religious and nationalist fundamentalism.In this second sense culture is a sort of theater where various political andideological causes engage one another. Far from being a placid realm ofApollonian gentility, culture can even be a battleground on which causesexpose themselves to the light of day and contend with one another, makingit apparent that, for instance, American, French, or Indian students who aretaught to read their national classics before they read others are expected toappreciate and belong ioyally, often uncritically, to their nations and traditions while denigrating or fighting against others.Now the trouble with this idea of culture is that it entails not onlyvenerating one's own culture but also thinking of it as somehow divorcedfrom, because transcending, the everyday world. Most professional humanists as a result are unable to make the connection between the prolonged andsordid cruelty of practices s-qch as slavery, colonialist and racial oppression,

xivIntroductionand imperial subjection on the one hand, and the poetry, fiction, philosophyof the society that engages in these practices on the other. One of the difficulttruths I discovered in working on this book is how very few of the Britishor French artists whom I admir took issue with the notion of "subject" or"inferior" races so prevalent among officials who practiced those ideas as amatter of course in ruling India or Algeria. They were widely acceptednotions; and they helped fuel the imperial acquisition of territories in Africathroughout the nineteenth century. In thinking of Carlyle or Ruskin, or evenof Dickens and Thackeray, critics have often, I believe, relegated thesewriters' ideas about colonial expansion, inferior races, or "niggers" to a verydifferent department from that of culture, culture being the elevated area ofactivity in which they "truly" belong and in which they did their ''really"important work.Culture conceived in this way can become a protective enclosure: checkyour politics at the door before you enter it. As someone who has spent hisentire professional life teaching literature, yet who also grew up in the, pre-World War Two colonial world, I have found it a challenge not to seeculture in this way-that is, antiseptically quarantined from its worldlyaffiliations--but as an extraordinarily varied field of endeavor. The novelsand other books I consider here I analyze because first of all I find themestimable and admirable works of art and learning, in which l and manyother readers take pleasure and from which we derive profit. Second, thechallenge is to connect them not only with that pleasure and profit but alsowith the imperial process of which they were manifestly and unconcealedlya pan; rather than condemning or ignoring their participation in what wasan unquestioned reality in their societies, I suggest that what we learn aboutthis hitherto ignored aspect actually and truly enhances our reading andunderstanding of them.Let me say a little here about what I have in mind, using two well-knownand very great novels. Dickens's Great Expectlltions (1861) is primarily a novelabout self-delusion, about Pip's vain attempts to become a gentleman withneither the hard work nor the aristocratic source of income required for sucha role. Early in life he helps a condemned convict, Abel Magwitch, who, afterbeing transported to Australia, pays back his young benefactor with largesums of money; because the lawyer involved says nothing as he disburses themoney, Pip persuades himself that an elderly gentlewoman, Miss Havisham,h·as been his patron. Magwitch then reappears illegally in London, unwelcomed by Pip because every.thing about the man reeks of delinquency andunpleasantness. In the end, though, Pip is reconciled to Magwitch and to hisreality: he finally acknowledges Magwitch-hun ed, apprehended, and fatally ill-as his surrogate father, not as someone to be denied or rejected,

IntroductionXVthough Magwitch is in fact unacceptable, being from Australia, a penalcolony designed for the rehabilitation·but not the repatriation of transportedEnglish criminals.Most, if not all, readings of this remarkable wor situate it squarely withinthe metropolitan history of British fiction, whereas I believe that it belongsin a history both more inclusive and more dynamic than such interpretationsallow. It has been left to two more recent books than Dickens's--RobertHughes's magisterial The Fatal Shrwe and Paul Carter's brilliantly speculativeThe Road to Botany Bay-to reveal a vast history of speculation about andexperience of Australia, a "white" colony like Ireland, in which we canlocate Magwitch and Dickens not as mere coincidental references in thathistory, but as participants in it, through the novel and through a much olderand wider experience between England and its overseas territories.Australia was established as a penal colony in the late eighteenth centurymainly so that England could transport an irredeemable, unwanted excesspopulation of felons to a place, originally charted by Captain Cook, thatwould also function as a colony replacing those lost in America. The pursuitof profit, the building of empire, and what Hughes calls social apartheidtogether produced modern Australia, which by the time Dickens first tookan interest in it during the 184os (in David Copperfield Wilkins Micawberhappily immigrates there) had progressed somewhat into profitability and asort of "free system" where laborers could do well on their own if allowedto do so. Yet in MagwitchDickens ·knotted several strands in the English perception of convictsin Australia at the end of transportation. They could succeed, but theycould hardly, in the real sense, return. They could expiate their crimesin a technical, legal sense, but what they suffered there warped theminto pertnanent outsiders. And yet they were capable of redemptionas long as they stayed in Australia.1Carter's exploration of what he calls Australia's spatial history offers usanother version of that same experience. Here explorers, convicts, ethnographers, profiteers, soldiers chart the vast and relatively empty continent eachin a discourse that jostles, displaces, or incorporates the others. Botany Bayis therefore first of all an Enlightenment discourse of travel and discovery,then a set of travelling narrators (including Cook) whose words, charts, andintentions accumulate the strange territories and gradually turn them into"home." The adjacence between the Benthamite organization of space(which produced the city of Melbourne) and 'the apparent disorder of theAustralian bush is shown by Carter to have become an optimistic transfor-

:xviIntrotluctionmarion of social space, which produced an Elysium for gendemen, an Edenfor laborers in the 184os.z What Dickens envisions for Pip, being Magwitch's"London gentleman," is roughly equivalent to what was envisioned byEnglish benevolence for Australia, one social space authorizing another.But Great Expectlltion.r was not written with anything like the concern fornative Australian accounts that Hughes or Carter has, nor did it presume orforecast a tradition of Australian writing, which in fact came later to includ the literary works of David Malouf, Peter Carey, ,and Patrick White. Theprohibition placed on Magwitch's rerum is not only penal but imperial:subjects can be taken to places like Australia, but they cannot be allowed a"return" to metropolitan space, which, as all Dickens's fiction testifies, ismeticulously charted, spoken for, inhabited by a hierarchy of metropolitanpersonages. So on the one hand, interpreters like Hughes and Carter expandon the relatively attenuated presence of Australia in nineteenth-centuryBritish writing, expressing the fullness and earned integrity of an Australianhistory that became independent from Britain's in the twentieth century;yet, on the other, an ·accurate reading of Great Exper:mtion.r must note thatafter Magwitch's delinquency is expiated, so to speak, after Pip redemptively acknowledges his debt to the old, bitterly energized, and vengefulconvict, Pip himself collapses and is revived in two explicitly positive ways.A new Pip appears, less laden than the old Pip with the chains of thepast-he is glimpsed in the form of a child, also called Pip; and the old Piptakes on a new career with his boyhood friend Herbert Pocket, this time notas an idle gentleman but as a hardworking trader in the East, where Britain'sother colonies offer a sort of normality that Australia never could.Thus even as Dickens settles the difficulty with Australia, another structure of attitude and reference emerges to suggest Britain's imperial intercourse through trade and travel with the Orient. In his new career as colonialbusinessman, Pip is hardly an exceptional figure, since nearly aU of Dickens'sbusinessmen, wayward relatives, and frightening outsiders have a fairlynormal and secure connection with the empire. But it is only in recent yearsthat these connections have taken on interpretative importance. A newgeneration of scholars and critics-the children of decolonization in someinstances, the beneficiaries (like sexual, religious, and racial minorities) ofadvances in human freedom at home-have seen in such great texts ofWestern literature a standing interest in what was considered a lesser world,populated with lesser people of color, portrayed as open to the interventionof so many Robinson Crusoes.By the end of the nineteenth century the empire is no longer merely ashadowy presence, or embodied merely in the unwelcome appearance of afugitive convict but, in the works of writers like Conrad, Kipling, Gide, and

Introductionxvii, Loti, a central area of concern. Conrad's !Vostromo (1904)--my second example-is set in a Central American republic, independent (unlike the Africanand East Asian colonial settings of his earlier fictions), and dominated at thesame time by outside interests because of its immense silver mine. For acontemporary American the most compelling aspect of the work is Conrad'sprescience: he forecasts the,unstoppable unrest and "misrule" of the LatinAmerican republics (governing them, he says, quoting Bolivar, is like plowing the sea), and he singles out North America's particular way ofinfluencing conditions in a decisive yet barely visible way. Holroyd, the SanFrancisco financier who backs Charles Gould, the British owner of the SanTome mine, warns his protege that "we won't be drawn into any largetrouble" as investors. Nevertheless,We can s

Culture and imperialism/Edward W. Said-1st Vintage Booka ed. P· em. Originallypubliohed: New York: Knopf, 1993. Includes bibliogr phical rcti.rences and index. ISBN 0-679-75054-1 I. European literature - Hiotory and criticism-Theory, etc. 2. Uterarore-Hiororyand criticism-Theory, etc. 3. Imperialism in literature. 4. Colonies in literature. 5.

The Age of Imperialism The period between 1870 and 1914 has often been called the Age of Imperialism. Imperialism is the policy of powerful countries seeking to control the economic and political affairs of weaker countries or regions. During this period the United States and Japan became the imperial powers. One reason for the growth of imperialism is because

The New Imperialism European countries controlled only small part of Africa in 1880; but by 1914 only Ethiopia, Liberia remained independent. European powers rapidly divided Africa Period known as “Scramble for Africa” Most visible example of new imperialism New imperialism not based on settlement of colonies European powers worked to directly govern large areas occupied by

tive of history and an attitude about history. The lived experiences of imperialism and colonialism contribute another dimension to the ways in which terms like 'imperialism' can be understood. This is a dimen sion that indigenous peoples know and understand well. In this chapter the intention is to discuss and contextualise four

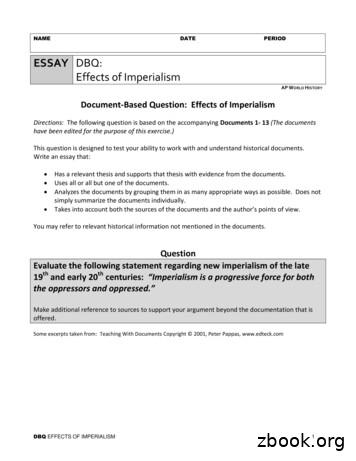

DBQ EFFECTS OF IMPERIALISM 2 Document 1 From: Imperialism and World Politics, Parker T. Moore, 1926 To begin with, there are the exporters and manufacturers of certain goods used in the . Latin America, and Asia]. Under [the progressive nations] direction, these places can yield tropical

Imperialism in Central Asia and Southeast Asia The Scramble for Africa European Imperialism in the Pacific The Emergence of New Imperial Powers U.S. Imperialism in Latin America and the Pacific Imperial Japan Legacies of

European countries controlled only small part of Africa in 1880; but by 1914 only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent. Under New Imperialism, European powers competed to rapidly divide up Africa Period known as ―Scramble for Africa‖ – Most visible example of new imperialism – New imperialism not based on settlement of colonies

European countries controlled only small part of Africa in 1880; but by 1914 only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent. Under New Imperialism, European powers competed to rapidly divide up Africa Period known as ―Scramble for Africa‖ – Most visible example of new imperialism – New imperialism not based on settlement of colonies

Introduction, Description Logics Petr K remen petr.kremen@fel.cvut.cz October 5, 2015 Petr K remen petr.kremen@fel.cvut.cz Introduction, Description Logics October 5, 2015 1 / 118. Our plan 1 Course Information 2 Towards Description Logics 3 Logics 4 Semantic Networks and Frames 5 Towards Description Logics 6 ALCLanguage Petr K remen petr.kremen@fel.cvut.cz Introduction, Description Logics .