China Competition Not Your Mother’s Cold War: India’s .

The Washington QuarterlyISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwaq20Not Your Mother’s Cold War: India’s Options in USChina CompetitionTanvi MadanTo cite this article: Tanvi Madan (2020) Not Your Mother’s Cold War: India’s Options in US-ChinaCompetition, The Washington Quarterly, 43:4, 41-62To link to this article: shed online: 11 Dec 2020.Submit your article to this journalView related articlesView Crossmark dataFull Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found ation?journalCode rwaq20

Tanvi MadanNot Your Mother’s ColdWar: India’s Options inUS-China CompetitionEven before the 2020 China-India boundary crisis, there was some discussion about how India would approach intensifying Sino-US competition. InIndia, there has been a tendency to compare it to Delhi’s options during theCold War, with many arguing that alliances are anathema and therefore Indiawould and should remain non-aligned. Other possibilities put forth have includedIndia as a swing state between China and the United States. Yet others—oftenoutside India—suggest that Delhi will have to choose.1 Since the Sino-Indianboundary crisis broke out in May 2020, the discussion has turned to whetheror not the skirmishes would, or should, lead India to “pick a side” in unfoldingSino-US competition.However, this debate neglects two important considerations. First, India’soptions vis-à-vis Sino-US competition today and in the future will not necessarilybe the same as they were with US-Soviet competition during the Cold War.Second, the non-alignment versus alliance framing derived from Cold War narratives neither accurately captures the past Indian approach nor will fully explainits future stance. Ignoring these two elements will lead to assumptions and analyses in Delhi, Beijing, and Washington that could result in missed opportunitiesor misleading assessments.This article first considers the Cold War analogy, examining the ways in whichDelhi might find Sino-US competition to be similar to or different from US-Sovietcompetition, particularly given the nature of India’s relationships with China andTanvi Madan is Director of the India Project at the Brookings Institution, where she also is asenior fellow in the Foreign Policy program. She is the author of Fateful Triangle: How ChinaShaped US-India Relations during the Cold War (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press,2020) and can be followed on Twitter @tanvi madan. 2020 The Elliott School of International AffairsThe Washington Quarterly 43:4 pp. 18THE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 202141

Tanvi Madanthe United States. Next, it explores the problems with framing India’s choices asthe ones derived from the Cold War—non-alignment or alliance—pointing outthe pitfalls that can follow from India, China, or the United States over-readingthe Cold War comparison. The article concludes with a glimpse into what achoice between non-alignment and alliance—i.e., alignment—could look likefor India’s relationship with the United States and what it would require.The Cold War Analogy: Why It ResonatesFor many, present-day great power competition has brought to mind US-Sovietcompetition during the Cold War, even as the debate about the suitability of thisanalogy continues.2 In 2018, speaking to the parliamentary committee on external affairs, the Indian foreign secretary alluded to this analogy, noting that theworld “may be moving back into an age of bipolarity or certainly one wheretwo countries, United States and China, have put forward ideological position[s] about what Foreign Policy consists of.” Furthermore, he spoke of China’s“community for the shared future of mankind juxtaposed to the UnitedStates Cold War System of Alliances.”3It is not surprising that such comparisons are being made in India too. Afterall, there are certain similarities. Long-term competition looms between twocountries with which India engages diplomatically and economically. Just asUS-Soviet competition did, US-China rivalry will help shape—if not be theprimary context of—the global and regional environment facing Indian policymakers. And this competition is likely to play out across multiple domains—geopolitical, economic, technological, and ideological—as well as a number ofregions and international institutions.As in the Cold War, actors beyond the superpowers will matter to the broaderbalance of power, and they will try to exercise agency based on their own perceptions and interests. India will seek to do so too. Just like in the past, Indian policymakers will try to maintain as much strategic and decisional autonomy as possiblewhile ensuring the country’s security and prosperity. In part, they will do so byplaying a role on the global and regional stage to shape India’s environment.And, just as it did during the Cold War, Delhi will try to achieve these objectives by using Sino-US rivalry to elicit benefits from both antagonists. Whilehoping that competition does not escalate to conflict or destabilize India’s neighborhood, Delhi will also—and perhaps to a greater extent—worry about potentialcooperation between the two antagonists that could adversely affect its interests,including by constraining its choices or diminishing its utility. During the ColdWar, for instance, Delhi looked askance at US-Soviet cooperation on nonproliferation.42THE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 2021

Not Your Mother’s Cold WarDelhi will also have concerns about the main antagonists deepening ties withIndia’s rivals. During the Cold War, these concerns arose from a few differentsources: the US partnership with Pakistan in the 1950s, 1971, and after 1979;the Sino-Soviet alliance; Soviet flirtations with Pakistan in the mid-to-late1960s; and US-China rapprochement in 1971. Eachof these complicated India’s options.elhi sought toDuring US-Soviet competition, Delhi sought towork with otherwork with other countries to help navigate bipolarcompetition, attempting to pursue a strategy of divercountries to helpsification by seeking partnerships with a number ofnavigate bipolarmajor and middle powers. It did so to create spacefor itself, avoid overdependence on one partnercompetition(and the strings that came attached with that), andhedge against the uncertainty about or unreliabilityof Moscow and Washington as partners. Delhi will likely pursue this pathagain, for somewhat similar reasons.Another area of resonance will be Beijing and Washington’s interest in Delhi’sportfolio of partners. During the Cold War, Moscow and Washington closelywatched Delhi’s partnerships, especially to assess the impact on the balance ofpower. They approved of—and even encouraged—India’s ties with their ownpartners. However, Delhi’s relationships with their main rival and the rival’sallies and partners created uneasiness and complicated their own ties withIndia. For instance, the Soviet Union frowned upon and tried to limit Indianengagement with the United States and China at different times. Washington,for its part, was wary of Delhi’s ties with Beijing and Moscow. Its discomfortpartly stemmed from concern that these ties would lead India to limit itscooperation with the United States either preemptively or resultantly (reprisedby American concerns today, for instance, about India’s acquisition of Russianmilitary platforms).4 This unease ironically led Washington itself to limitcooperation with India, particular in the defense supply realm.DFive Reasons Why This Competitive Era is DifferentHowever, there are some key dissimilarities from the Cold War that will affectDelhi’s perceptions and options today.InterdependenceCompared to the Cold War, today’s two major competitors (and particularly theireconomies) are more intertwined. In some crucial ways, they are more interdependent on each other than they are with India. The stock of US ForeignTHE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 202143

Tanvi MadanDirect Investments (FDI) in China and India in 2019, for instance, was US 116billion and US 46 billion, respectively; Chinese and Indian FDI in the UnitedStates for that year was US 59 billion and US 17 billion. At US 558 billionin goods alone, US-China trade dwarfs US-India trade (US 92 billion) andIndia-China (US 82 billion) trade.5 This was not the case during the ColdWar, when India was in many ways more connected with the Soviet Unionand the United States than they were with each other.6This Sino-US interdependence will continue to fuel Indian policymakers’worries—greater than any Cold War concern about a US-Soviet grand bargain—that a US-China condominium, deal, or G2 will materialize. On the flipside, it could also magnify the frictions and expand the battlespace betweenthe two countries in ways that could benefit or harm India’s interests. On theone hand, Delhi shares many of Washington’s(and Europe’s) concerns about Beijing’s econino-US interdeomic policies and practices, including the lackof reciprocity. A collective or coordinatedpendence will conapproach toward China in this regard istinue to fuel Indianmuch more likely to be effective than anypolicymakers’efforts Delhi might alone make with Beijing.On the other hand, Delhi will closely watchworrieshow any Sino-US decoupling or disentanglingplays out—if couched or applied broadly, someAmerican trade, investment, and immigration policies sparked by China competition could adversely affect India too. Moreover, there is concern about theimplications for India of a fragmented digital space resulting from Sino-US technology competition in ways that are very different from and more widespreadthan the Cold War.7SConfiguration of PowerThe global configuration of power, as historian Melvyn Leffler put it, is alsodifferent today,8 hence the debate about bipolarity versus multipolarity as thebest descriptor for the present and likely future context. There are a number ofmajor and middle powers, particularly in Asia. And while many, includingIndia, might be more like-minded with the United States, they also have tieswith China. Most have not joined—and do not want to join—one bloc. Thislandscape of like-minded powers, a number of which are seeking to retain theirstrategic autonomy in part through diversification, will give Delhi more potentialpartners, in line with its own desire to diversify. However, those countries’ tieswith Beijing could also limit how far and fast some of them will wish to cooperatewith India.44THE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 2021

Not Your Mother’s Cold WarIndia’s own power and position are different today. Delhi played an active rolein Asia and even globally during the first decade and a half of the Cold War, butthere was a sense that it was punching above its weight. In 1947, the US government considered India to be in the category of least important countries from itsperspective, lacking military-industrial capacity and skilled manpower.9 Today,India is a state that has one of the largest militaries in the world, nuclearweapons, an economy that is larger than three of the P-5 countries (which hasmade it an aid donor rather than a major aid recipient), and membership in anumber of key institutions. It is a country that is being actively sought out as apartner. This position gives India more space, but it will also make stayingaloof from key discussions and debates more difficult.Location, Location, LocationAnother key difference from the Cold War is that Asia—or the Indo-Pacific, ifyou prefer—is likely to be the primary theater for this competition, not a secondary or associated one as it was in the Cold War. One of the great power antagonists is India’s neighbor, unlike the Cold War when the two main competitors wererelatively distant actors. Part of Delhi’s approach then was to try to resist theircompetition spilling over into South Asia and the Indian Ocean region, buttoday’s Sino-US competition is literally taking place at India’s doorstep. Thatproximity makes sitting the competition out, as some have suggested, an unrealistic option for Delhi.10 But having China as a neighbor also shapes India’s perception of the Chinese threat and makes it vulnerable to a different kind ofleverage than either of the superpowers had with India during the Cold War.The Moscow FactorFor most of the Cold War, India found a willing partner in the Soviet Union.There were two periods when this was not the case: the Stalin years andaround the 1962 Sino-Indian war when Moscow had to choose between its alliance with China and its friendship with India. It chose to either support Beijingor decline to help Delhi. However, the Sino-Soviet split removed that obstacle toIndia’s benefit.The narrative and the stronger memory in India is of the period that followed,when the Soviet Union partnered with India against China and helped enhanceIndian military capabilities. However, today’s close—and many argue deepening—Sino-Russian relationship is more akin to the situation Delhi faced in the earlyCold War. On balance, this Sino-Russian partnership is to India’s detriment. ForIndia, Russia has traditionally been a key part of its competitive strategy vis-à-visChina, as a balancer and a supplier of military equipment and technology. Thus,it looks askance at Moscow’s deepening military and technological ties—whichTHE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 202145

Tanvi MadanVladimir Putin recently highlighted—and their cooperation and coordination onthe global stage.11Delhi is hoping for a replay of the Cold War Sino-Soviet split, and that, like atone point in the 1960s, both Moscow and Washington will help Delhi balance ordeter Beijing. Thus, it has been urging the West to create a wedge between Chinaand Russia, but India will have to plan for this split not materializing—or at leastnot in a time frame that Delhi would prefer.12India’s Relationships with the Great Power CompetitorsPerhaps the most significant difference for India is that it has major problemswith one of the two great power antagonists—indeed, it sees China as its keyexternal strategic challenge. Though Delhi had certain differences withMoscow or Washington during the Coldhe mostWar, these were not fundamental disputes orsignificant differenceconflicts of interest. Today, India has a longstanding territorial dispute with China, andis that India itself haseven as Sino-US competition has been intenmajor problemssifying over the last decade, this boundaryproblem has flared up repeatedly. Since Xiwith ChinaJinping took the helm in Beijing, there havebeen four significant stand-offs between theChinese and Indian militaries after years ofrelative calm: at Depsang (2013), Chumar (2014), Doklam (2017), and in2020 at multiple points in Ladakh. The latter resulted in the first fatalities atthe Sino-Indian boundary in 45 years.13Other bilateral differences include Chinese concerns about the presence of theDalai Lama and Tibetan refugees in India—an issue that is unlikely to staydormant as the subject of the next Dalai Lama looms. Then there are Indian concerns about Chinese dam construction on the Brahmaputra river, its potentialdiversion, and the erosion of Indian usage rights. There is also a series of bilateraleconomic differences, including India’s concerns about its large trade deficit withChina (30 percent of its total14), lack of reciprocity, intellectual property, overdependence on China for industrial inputs, Beijing’s influence over Chinese companies that have made inroads into key sectors in India, and the potential foreconomic coercion.Another major concern for Delhi is China’s strategic relationship with India’sother main rival, Pakistan, which has deepened and broadened in recent years.The close Sino-Pakistani relationship has a number of implications for India,including for military planning. For instance, in the past, Delhi has worriedabout Chinese intervention in India-Pakistan conflicts (1965 and 1971) andT46THE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 2021

Not Your Mother’s Cold WarPakistani activity requiring India to divert resources from the China front (1962).Indian officials have long worried about—and had to undertake planning for—atwo-front war. The 2020 boundary crisis has only intensified this concern.15China and India also have differences in the region and divergent visions.16Delhi has watched warily as China has expanded its strategic, economic, andpolitical activities as well as influence India’s neighborhood—continentaland maritime—contributing to India’s resistance to China’s Belt and RoadInitiative (BRI).17 Moreover, it believes that Beijing wants a unipolar Asia,while India seeks a multipolar region. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modialluded to this and other differences in his speech at the Shangri-La Dialoguein 2018, which also indicated that India welcomed a role for actors frombeyond the region (i.e., the United States) as opposed to an Asia for Asiansview.18On the global stage, Delhi sees Beijing as limiting India’s space. For instance,China is the only P-5 country not to endorse a permanent seat for India as part ofany UN Security Council reform, and it has resisted Indian membership of theNuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). Beijing has also blocked Indian efforts to getPakistan-based individuals designated as terrorists by the UN’s 1267 committee,tried to designate an Indian as a terrorist, and raised the issue of Kashmir at theUN. In each case, the United States ranged itself on India’s side, helping overcome the hold in the 1267 committee and blocking the other two Chinesemoves.19 There is an overarching sentiment in India that these Chineseapproaches—as well as the country’s support for Pakistan more generally—reflect Beijing’s desire to prevent India’s rise and keep it bogged down inSouth Asia. This is a change from the 1970s and 1980s when many Indiansbelieved this was Washington’s goal; today they find American administrationsroutinely endorsing the idea that India’s rise is in America’s interest.20Moreover, Sino-Indian competition has been playing out in the context of awidening gap between the Chinese and Indian economies and militaries. Forinstance, in 1989, the two economies were about the same size; in 2019, just30 years later, the Chinese economy was almost five times that of India.21 Andunderlying all these developments is a low level of Indian trust in China. Thisproblem has become more acute as a result of the boundary crisis, with Delhiseeing Beijing as having violated the existing agreements between the twocountries.Compare these grievances to the list of India’s differences with the UnitedStates. These include some economic differences, but nowhere near the scaleof Sino-Indian or Sino-US divergences. India’s partnership with Russia, particularly its acquisition of platforms like the S-400 missile defense system, poses aproblem for Washington. On Capitol Hill, there are a set of concerns aboutthe state of liberalism, religious freedom, and human rights in India. Delhi,THE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY WINTER 202147

Tanvi Madanmeanwhile, worries about US decisions vis-à-vis Afghanistan and what thatcould mean for Pakistan. It also has concerns about Washington’s approach toimmigration. Then there are Indian concerns about its options being constrainedbecause of American approaches to third countries, like Iran, or its withdrawalfrom agreements, like the Paris climate agreement. But part of the reasonDelhi works to manage these differences with Washington is that it sees theUnited States as a solution to some of the problems it has with China.What about the argument that, like with the Cold War superpowers, Delhiengages with both China and the United States bilaterally, regionally, and ininternational institutions? It is true that India labels ties with both as partnerships,22 but its relationship with China has been fundamentally competitivefor decades and is now incr

The Cold War Analogy: Why It Resonates For many, present-day great power competition has brought to mind US-Soviet competition during the Cold War, even as the debate about the suitability of this analogy continues.2 In 2018, speaking to the parliamentary committee on exter-

Novena Prayer Dearest Mother of Perpetual Help, from the cross Jesus gave you to us for our Mother. You are the kindest, the most loving of all mothers. . Mother of Perpetual Help, we choose you as Queen of our homes. We ask you to bless all our families with your tender motherly love. May theFile Size: 7MBPage Count: 58Explore furtherA Short Novena to Our Mother of Perpetual Helpwww.cathedralokc.orgOur Mother of Perpetual Help 9 Days Novena Prayer - Day 1www.god-answers-prayers.comOur Mother of Perpetual Help Wednesday Novena Prayergod-answers-prayers.comNOVENA TO OUR MOTHER OF PERPETUAL HELP OPENI www.baclaranchurch.orgNovena in Honor of Our Mother of Perpetual Help 1redemptoristsdenver.orgRecommended to you b

WEI Yi-min, China XU Ming-gang, China YANG Jian-chang, China ZHAO Chun-jiang, China ZHAO Ming, China Members Associate Executive Editor-in-Chief LU Wen-ru, China Michael T. Clegg, USA BAI You-lu, China BI Yang, China BIAN Xin-min, China CAI Hui-yi, China CAI Xue-peng, China CAI Zu-cong,

Mother and Model of the Christian Life On the Cross, Jesus gave His Mother to John the Apostle to care for. In doing so, not only did Jesus show His great love for His Mother, but He also gave her to all of us. Mary is the Mother of God, but also the Mother of the Church and our Mother too. Therefore, we honor Mary in such a way

Mother’s Day Novena Mother’s Day Novena Mother’s Day Novena Mother’s Day Novena Mother’s Day Novena Mother’s Day Novena Acts 16:11-15; John 15:26—16:4a 8:30 a.m. Mother’s Day Novena Tuesday, May 11 Easter Weekday Acts 16:22-34; John 16:5-11 8:30 a.m. Moth

Date of birth 3. Time of birth 4. Sex 5. Facility name 6. City, town, or location of birth 7. County of birth 8a. Mother/Parent's current legal name 8b. Mother's date of birth 8c. Mother's age 9. Mother's name prior to first marriage 10. Mother's birthplace 11a. Residence of Mother (state) 11b. Mother's county 11c.

more are The Seven Daughters of Eve; Saxons, Vikings, and Celts; and Adam’s Curse by Dr. Bryan Sykes. It is important to note that DNA analysis applies ONLY to your direct paternal (your father, your father's father, your father's father's father, etc.) and direct maternal (your mother, her mother, your mother's mother's mother, etc.) lines.

Abduljaleel Fadhil Jamil-The Portrait of the Mother in “Mother Courage and Her Children” by Bertolt Brecht EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH - Vol. IV, Issue 12 / March 2017 10454 MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN: OVERVIEW Brecht wrote Mother Courage and Her Children in Sweden during his exile for Germany.

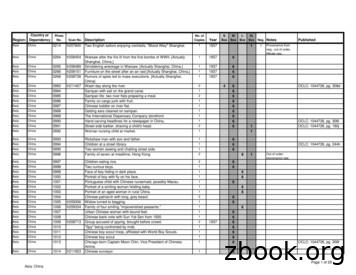

Asia China 1048 Young man eating a bowl of rice, southern China. 1 7 Asia China 1049 Boy eating bowl of rice, while friend watches camera. 1 7 Asia China 1050 Finishing a bowl of rice while a friend looks over. 1 7 Asia China 1051 Boy in straw hat laughing. 1 7 Asia China 1052 fr213536 Some of the Flying Tigers en route to China via Singapore .