BEE NEWS & VIEWS

BEE NEWS & VIEWSThe Mississippi Beekeepers Association NewsletterJEFF HARRIS, EditorPhone: 662.769.8899July-August 2016MBA Annual ConventionBy Austin SmithThe annual convention of the MississippiBeekeepers Association (MBA) will be held onNovember 4-5, 2016. It will be held at RamadaAirport Convention Center, 9415 Highway 49,Gulfport, MS 39503 (ph. 228-868-8200). The roomrate is 67.19 per, which includes taxes.We are still working on the program, but speakerswill include scientists from the USDA, ARS HoneyBee Lab in Baton Rouge, Jennifer Berry for theUniversity of Georgia, Carl Webb from Georgia,Dan Conlon, a member of the Russian Honey BeeBreeders Association. Local speakers will includeMilton Henderson, the MSU Apiculture programstaff and other MBA members. Registration formsfor MBA membership and for the annual conferencehave been attached to this email. They should becompleted and returned by October 21, 2016. Forbeginners and hobby beekeepers, please note thatspecial workshop sessions will be ongoing on Fridayafternoon and all day on Saturday.If you would like to bring a door prize, feel free to doso and note it on your pre-registration form. Justreport it at the registration desk as you arrive onFriday. Giving away door prizes is a way to spice upa meeting. We also seek items that could be used ina silent auction. We encourage you to bring items forthe silent auction related to beekeeping (even onesyou no longer use but are still in good condition),crafts (paintings, stitch work, etc.), tools (everybeekeeper needs tools in the shop), or otherinteresting/ unique items. Silent auction items shouldbe brought in no later than Saturday, Nov. 5 @ 8AM.Please contact Joe Scott [phone: 228.669.8336 oremail: elevenoaks58@cableone.net] if you wish tomail your donated items for either the silent auctionor for door prizes. His mailing address (where tosend door prize donations) is: 23416 Meaut Road,Pass Christian, MS 39571. Thanks for your time andsupport of beekeeping in Mississippi, and I lookforward to seeing you in November.The schedule for the convention will be similar tolast year. We will hold a Board of Directors meetingon Friday morning (TBA).Afterwards, theconvention will begin Friday at noon and continueuntil 5:30 PM. The banquet dinner will begin at 6:30PM, and there will be some entertainment from alocal performer during the meal. We will resume theconvention on Saturday morning at 8:00 AM, and itwill end at 5:00 PM on Saturday. The MBA businessmeeting will immediately follow the convention.Jeff Harris is still developing the program for theconvention, and when it is completed, he will post iton his website and via email.Please note that the conference pre-registration fee is 25, and registration at the door will be 35.00. Also,we ask everyone to renew their normal MBAmemberships in the months of September-Octoberevery year. We do not want renewals streamingthrough the entire year. So, please, just get into thehabit of renewing your MBA membership duringSeptember through October of each year.Additionally, there will be the Honey and WaxContest. If you would like to participate, please seethe rules for entering and judging standards at theMSUCares s/2014/08/JUDGING-STANDARDS.pdf).We are looking forward to a very fine meeting, and Ihope you can join the fun and festivities.

Thermoregulation of the HiveBy Audrey Sheridan & Clarence H. CollisonThe internal temperature of a honey bee hive rangesfrom 31 C in the periphery to 36 C in the brood nest,regardless of ambient environmental conditions. Theprocess by which worker bees maintain a tion’, and it is crucial to the properdevelopment of larvae to adults.Capped pupae are especially sensitive to drasticchanges in temperature. If the brood area remainsbelow 32 C for too long, there is a high incidence ofdeformed wings, legs and abdomens, and emergedadults may exhibit neurological and behavioralabnormalities; eggs and larvae in open cells are lesssensitive to prolonged drops in temperature. Broodnest temperatures above 36 C for any prolongedperiod are equally detrimental to brood (Yang et al.2010). Thus, thermoregulation is a high priority incolonies rearing brood, but more variable in theabsence of brood (Stabentheiner et al. 2010).Summertime thermoregulation is achieved throughevaporative cooling. Workers collect water anddeposit it in empty cells within the brood chamber,then fan the water vigorously. Water collection is aspecialized task, like pollen or nectar foraging, andbees assigned to this task appear to perform onlyduties related to hive cooling. Kühnholz and Seeley(1997) studied the behavior of water-collectors inhoney bee colonies, and reported an increase in thenumber of water collectors during a heat-stress event.Heat lamps were used to bring brood nesttemperatures up to approximately 42.5 C, and thenumber of water collectors rose slowly but steadilyuntil well after the peak temperature was reached.However, when heat lamps were turned off, watercollection dropped abruptly. Water-collecting beespassed their loads off to water-receiving bees at thehive entrance, rather than bringing it insidethemselves. Water receivers tended to deposit theirwater loads in empty cells in the brood nest, smearingit on the sides and ceilings. They also occasionallyventilated the hive.To the observer, the act of hive cooling isdemonstrated by a line of bees stretched across thehive entrance fanning their wings furiously. Withinthe brood nest, fanning workers form chains facingthe same direction to move air over their developingyoung. The direction in which worker bees circulateair from the hive entrance differs among species ofhoney bees: Apis cerana orients itself head-in-tailout at the hive entrance and fans cool ambient air intothe hive; Apis mellifera faces the opposite directionand fans hot air out of the hive.Yan et al. (2010) attempted to elucidate thisdifference in interspecific hive cooling by studyingthe effects of combining the two species into a singlecolony and comparing their behavior with two purecolonies. Their research looked at the followingbehaviors in hybrid colonies: 1) whether workers ofboth species ventilated at the hive entrance; 2) if theyfanned with their natural body posture, or adoptedthe posture of the other species; and 3) whether theirventilation efficiency improved or worsenedcompared to a single-species colony.Experimental colonies were established with eitheran A. cerana queen or an A. mellifera queen, and bothA. mellifera and A. cerana workers. Pure colonies ofeach species served as controls. Test hives werefitted with small heaters and brought to an internaltemperature of 38 C. At this point the heaters wereremoved and cooling behavior of the bees wasrecorded until temperatures returned to normal. Inall mixed colonies, each species retained their naturalcooling posture at the hive entrance: A. mellifera,head out; A. cerana, head in. Interestingly, therewere significantly more A. cerana than A. melliferafanning at the entrance in both types of mixedcolonies, regardless of the queen species.2

steps), suggesting that these patrilines had a lowerthan average threshold for fanning. The responses ofdifferent patrilines to changes in ambienttemperature illustrate two important phenomena.First, patrilines undoubtedly vary in their responsesto changing temperature; and second, the proportionof fanning workers from different patrilines changeswith temperature.A comparison of control colonies showed that pureA. cerana colonies solicited a significantly greaternumber of entrance fanners and were more sensitivethan A. mellifera to temperature changes in the hive,which was exhibited in the early-onset of fanningwhen the hive was heated. However, A. melliferawere able to cool their hives faster on average (55minutes, versus 67 minutes for A. cerana) and withfewer workers fanning, indicating that drawing hotair out of the hive is more efficient than forcing coolair in. Results of the study showed a decrease incooling economy in mixed-species compared to pureA. mellifera colonies, but similar cooling efficacy inmixed and pure A. cerana colonies.Thermoregulation behaviors can also vary within asingle species of honey bee. Genetic variationamong patrilines was shown to have a significanteffect on the ability of workers to keep broodtemperatures stable. Jones et al. (2004) compared thethermoregulation efficiencies of colonies with asingle patriline to those having multiple patrilines.Colonies were assessed for their ability to achieveand maintain a proper temperature in the brood nest(ca. 35 C) when the ambient temperature was raisedto 40 C.Uniform patriline colonies had asignificantly higher variance than non-uniformcolonies with respect to the mean temperature. Inaddition, two colonies of five-patrilines each wereobserved for differences in fanning-onset thresholdsas temperatures increased. In both colonies tested,fanning workers were collected from the hiveentrance as hive temperatures were increased, andtheir paternity was determined using geneticmarkers. Some patrilines produced more fanningworkers than other patrilines for many or all of theexperimental temperatures (25 C to 40 C, in 1 CFanning is not the only technique honey bees employto regulate brood nest temperatures during thesummer months. Starks and Gilley (1999) showedthat worker bees shield brood against external heatby creating a physical barrier with their bodies, andabsorbing the excess heat. Workers can withstandtemperatures up to 50 C, while brood have athreshold of approximately 36 C. By placingheating pads on the outside of small observationhives, they were able to simulate heat stress to thebrood chamber of a hive, while observing workerbehavior through the glass pane. Worker bees wereattracted to the heated glass and clustered moredensely over the brood comb than the honey comb.There was no apparent buzzing of wings, and dronesand queens were excluded from the “shields”. Starksand Gilley proposed that in a natural environment,heat shielding may act as mobile insulation for nestcavity walls that are particularly thin and exposed tosunlight.Hive warming is achieved in a much more visuallysubtle way than hive cooling. In the winter, whenhive temperatures drop from 28 C (day) to 17 C(night), the metabolic rate of a honey bee colony risestremendously from 7 to 19 watts/kg of body mass(Wineman et al. 2003). The honey bee’s hair alsohelps to insulate the cluster: it has a plumosestructure, much like goose down, and when bees aretightly packed together it traps warm air within themass of bodies (Mangum 2001). But heat must begenerated continually to maintain a constant clustertemperature, especially during cold nights.The center of honey bee heat production is thethorax. This is also where the flight muscles arelocated. Honey bees produce heat by contractingtheir flight muscles very rapidly, a behavior referredto as “shivering”. This activity is not detectable tothe human eye, and heat-producing bees may appear3

to be at rest.The most intense heating isconcentrated in the brood area; as mentioned earlier,the pupae are the most susceptible to fluctuations intemperature. Brood-heating bees are positioned oneof two ways in the brood nest to transfer heat directlyto their young sisters: 1) headfirst in adjacent emptycells to warm brood from the side or, 2) pressingheated thoraces onto capped cells (Basile et al 2008).Cell heating can occur in intervals of 30 continuousminutes, which leaves heater bees quite depleted ofenergy stores. The brood nest is usually surroundedby pollen cells and the stored honey is locatedbeyond these. This would present a refuelingproblem for heater bees if they were expected to feedthemselves. Fortunately, heater bees are regularlyattended by food donors, who supply them with highpowered honey fuel. Basile et al (2008) observed thetrophallactic dynamic of donor and recipient bees inthe brood nest and found that donor bees are aseparate task specialization from nurse bees, as thedonors attend only brood warming bees, and notlarvae.development times are affected by ambienttemperatures; and 3) temperatures in the centralbrood nest differ from those around queen cells.Results of the first study showed that queen cellslocated in or adjacent to the brood nest were held athigher temperatures and had a greater chance ofemergence. In the second study, the position ofqueen cells migrated from the central brood nest tothe periphery of frames from winter to summer.However, queens took significantly more time tocomplete development in winter, spring and earlysummer.Results of the third study showedsignificantly higher temperatures in the central broodnest than the environment immediately surroundingqueen cells; the temperature gradient was also muchsmaller in the brood area. Due to the variability inemergence from queens of different patrilines, deGrandi-Hoffman et al. (1993) also proposed thatqueens from different patrilines could have differentdegree-day requirements for development. Thiswould genetically predispose certain lineages toemerge first and become reigning matriarchs.Heater bees continue to render their services evenafter the brood have completed their development.From a physiological standpoint, bees are not adultsas soon as they emerge from the brood nest. Theyare not capable of proper activation of their flightmuscles for either flight or endothermic heatproduction until they are several days old. It is notuntil 8-9 days of age that bees are morphologicallyand physiologically fully- developed. Therefore, forthe first week post-emergence, bees arepoikilothermic and stay close to the brood nest and,where the temperature is high and stable, until theyare able to generate their own heat (Stabentheiner etal. 2010).Although managed honey bees are capable ofhandling most temperature extremes that affect theirhives, beekeepers may want to enhance the bee’snatural thermoregulation with hive modifications,especially during cold winters. Applying an exteriortreatment to a hive during cold months can have anotable effect on colony thermoregulation.Wineman et al. (2003) showed that wrapping hivesin infra-red polyethylene sheets during a subtropicalwinter increased hive temperature, colonypopulation and spring honey production.Hive thermoregulation plays an important role inqueen rearing as well as brood production. DeGrandi-Hoffman et al. (1993) studied the effects oftemperature and position in the brood box on thedevelopment rate of queen bees. Three studies ofcolony thermoregulation were conducted todetermine if: 1) temperatures around queen cellsdiffer depending on their location in the brood nest,and if queen cell location influences queen survivalrates and emergence time; 2) the location of queencells differs throughout the year, and whether queenFurthermore, when compared with non-coveredhives, polyethylene-covered hives showed anincrease in brood area of 59%; non-covered hivesactually had an 8.4% reduction in brood area. Adultbee populations were increased by 37.5% in coveredhives and 11.8% in non-covered hives, and springhoney production was doubled in hives wrapped inpolyethylene. This research supports the use ofartificial hive insulation to increase colony viabilityduring the winter and following spring.4

ReferencesBasile R., C. W. W. Pirk and J. Tautz. 2008. Trophallacticactivities in the honeybee brood nest—heaters getsupplied with high performance fuel. Zoology 111: 433441.Coelho J. R. 1991. Heat transfer and body temperature inhoney bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) drones and workers.Environ. Entomol. 20(6): 1627-1635.DeGrandi-Hoffman G., M. Spivak and J. H. Martin. Role ofthermoregulation by nestmates on the development timeof honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) queens. Ann.Entomol. Soc. Amer. 86(2): 165-172.Jones J. C., M. R. Myerscough, S. Graham and B. P. Oldroyd.Honey bee nest thermoregulation: diversity une2004/Page1/10.1126/science.1096340.Audric de Campeau, who set up his first hives in theFrench capital in 2009, said he was surprised todiscover that his Parisian bees produced more thantwice as much honey as the ones he kept back in thenortheastern Champagne region.Mr. de Campeau said that green spaces in Paris andother large cities like New York or London actuallyhad a better mix of trees, flowers and other plantsthan farming areas dominated by vast single-cropfields. Plus: no crop-dusted pesticides.Honey produced in Paris tastes of red berries andlychee, Mr. de Campeau said. He said that traces ofthe city’s high air pollution had been found inbeeswax and the bees themselves, but that the beesstill lived longer than their country cousins.Kühnholz S. and T. Seeley. 1997. The control of watercollection in honey bee colonies. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.41: 407-422.Mangum W. A. 2001. Honey bee biology: the winter clusterup close. Amer. Bee J. 141(2): 101-103.Stabentheiner A., H. Kovac and R. Brodschneider. 2010.Honeybee colony thermoregulation—regulatorymechanisms and contribution of individuals independence on age, location and thermal stress. PLoSONE 5(1): e8967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.008967.Starks P. T. and D. C. Gilley. 1999. Heat shielding: a novelmethod of colonial thermoregulation in honey bees.Naturwiss. 86: 438-440.Wineman E., Y. Lensky and Y. Mahrer. 2003. Solar heatingof honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera L.) during thesubtropical winter and its impact on hive temperature,worker population and honey production. Amer. Bee J.143(7): 565-570.Yang M.-X., Z.-W. Wang, H. Li, Z.-Y. Zhang, K. Tan, S. E.Radloff and H. R. Hepburn. 2010. Thermoregulation inmixed-species colonies of honeybees (Apis cerana andApis mellifera). J. Insect Physiol. 56: 706-709.Urban Bees Make More HoneyBy The New York TimesIf you are a honeybee in France, the best place tolive (and work) might be smack in the middle ofParis.Bees were cultivated in Paris as far back as 1856, inthe Luxembourg Garden, where there is still abeekeeping school. Now, the local authorities count700 hives in parks, private residences and officebuildings.They have been set up on the rooftops ofthe National Assembly, France’s lower house ofParliament, and on top of the Palais Garnier operahouse, which sells small jars of its ownhoney online for 15 euros, or about 17.At the Tour d’Argent, a Left Bank restaurant, dinerscould recently enjoy “roast duckling with spices andhoney from our roof” as they took in the sweepingview of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame — whereseveral hives sit atop the sacristy.Even the French Communist Party recently set up ahandful of hives on the roof of its imposing 1970sera headquarters. One Twitter user wryly noted that5

the party was now in the capitalist business ofexploiting workers.A version of this article appeared in print on May 25, 2016, onpage A7 of the New York edition with the headline: Bees FindJoie de Vivre in Paris.Scientists Identify Gene Causing WorkerReproduction in Honey BeesBy The New York TimesThe female Cape bee is a renegade. She breaks allkinds of rules and disregards orders. In this isolatedsubspecies of honey bees from South Africa, femaleworker bees can escape their queen’s control, takeover other colonies and reproduce asexually — withno need for males. Scientists identified the genesmost likely to have instigated this unusuallypowerful worker bee behavior, according toa study published Thursday in PLOS Genetics.The typical story of reproduction is that males andfemales of an animal species do it sexually.Generally, that’s what honeybees do, too. Spermfrom a male drone fertilizes a queen’s eggs, and shesends out a chemical signal, or pheromone, thatrenders worker bees, which are all female, sterilewhen they detect it.But the Cape honeybee, a subspecies that lives inthe Fynbos ecoregion, a unique area of incrediblediversity along the southwestern tip of South Africa,evolved a workaround where, in some cases, femaleworkers can become something like a queen andproduce offspring of their own.Like all honeybees, some Cape bee colonies alsohave male drones. But female workers can startlaying their own eggs in their home colony when aqueen dies. These females will also invade coloniesof other honeybee subspecies and lay eggs in somecases, and they can enter undetected by bees thatwould normally kick them out.“The Cape bees will take over the foreign coloniesand start eating up all the honey,” said MatthewWebster, a geneticist at Uppsala University inSweden, who led the study. This behavior is calledsocial parasitism.To understand what was driving this behavior,researchers compared the whole genomes of 100honeybee subspecies with those of 10 Capehoneybees. Unsurprisingly, the genomes were verysimilar: The bees look and act the same in every wayexcept for the egg-laying quirk. But a few selectareas of the genome were unique on the Capehoneybee genome.“Normally that doesn’t cause really big differences,”said Dr. Webster. But in this particular bee, theworkers lay eggs that self-fertilize and becomefemale workers in their home colonies or the hivesthey invade.Genetic differences likely made social parasitismpossible by selecting for bees that could developovaries to a greater extent than other worker bees, layeggs prepackaged with two sets of chromosomes,and possibly emit a chemical signal to mask theirpresence while laying eggs, said Dr. Webster.This asexual tendency may sound weird, but it’s notunheard-of in biology. A variety of species of ants,wasps and bees can switch between sexual andasexual reproduction. And scientists havedocumented virgin births in turkeys, chickens, sharksand reptiles.During a process called thelytoky, two of the Capebee’s daughter cells fuse together to make a singlecell with both sets of chromosomes — just likeThelma the snake, a reticulated python known forher virgin births. Normally, honeybee eggs splitduring meiosis into four daughter cells with just oneset of chromosomes. Those turn into male droneswithout a father to contribute the other set to makethem female.What scientists haven’t sorted out is why there mightbe an evolutionary advantage for a female being ableto reproduce without a male. In extreme situationswith no males, it could mean the survival of herspecies. But then again, self-fertilization, the epitomeof inbreeding, could leave her offspring morevulnerable to disease and other threats.Dr. Webster hopes to elucidate why this adaptationon the Cape honeybee genome survived.6

“Why doesn’t it take over the whole world, and whydoesn’t it die out?” wondered Dr. Webster. “There’sno really good answer to that.”A version of this article appeared in print on June 10, 2016.Young Farmers and RanchersBy MSFB & Jeff HarrisThe Young Farmers and Ranchers program isdesigned to develop young people into the leadersthat will someday guide Mississippi Farm Bureau.Educating young farmers about the purpose andfunction of Farm Bureau and providing opportunitiesfor them to participate in the program structure ofFarm Bureau will prepare them to assume roles ofleadership in the organization.The YF&R program is designed for youngermembers, ages 18 – 35, who share an interest inimproving themselves and agriculture. They areencouraged to use their own knowledge and theinformation gained about Farm Bureau to helpformulate policies and programs that can lead tosolutions to their problems.Each year, the Young Farmer & Rancher Departmentsponsors the YF&R Achievement Award. Countywinners compete at the district level and districtwinners compete at the state level. The state winnerrepresents Mississippi in the American Farm BureauYF&R Contest.The YF&R Department also sponsors the YF&RExcellence in Agriculture Award each year. Thiscontestisdesignedtorecognizetheaccomplishments of contestants that derive themajority of their income from efforts other thanagriculture but are involved in farming and FarmBureau.One of the most interesting and rewarding programssponsored by the YF&R department inthe Discussion Meet where young people gettogether to discuss issues and problems affectingtheir way of life.I participated in a forum with this group that wassponsored by MSFB and the Mississippi StateUniversity Extension Service held at the BostExtension Center on the MSU campus in early July.My role was to explain to them the current status ofhoney bees in the U.S. and factors that have led toincreased mortality of colonies during the lastdecade or so.I stayed throughout the program and was amazed asto how much information was provided from all ofthe university specialists that spoke to the group.The newest issues in row crop farming (corn,soybean, cotton, and rice), cattle industry, lumberindustry, etc. were covered in great detail. Equallyimpressive was the eagerness to learn that I sensedfrom this group of young people. I left the eventfeeling like agriculture was in good hands with thenext generation.Antibiotic Use and theVeterinary Feed DirectiveBy Dr. Carla Huston, Extension Veterinarian, MSUWe enjoy one of the safest and most affordable foodsupplies in the world thanks to years of hard workby many—farmers, ranchers, veterinarians,processors, packers, distributors, governmentagencies, and others. To protect the gains made, it isthe responsibility of livestock producers tounderstand and follow the laws and be prepared tomeet the new and changing standards set in theyears to come.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) isresponsible for protecting public health by assuringthe safety, efficacy, and security of human andanimal drugs, biological products, and the foodsupply, among other things. The FDA Center forVeterinary Medicine (CVM) specifically regulatesanimal drugs, animal feeds, and animal devices. Allmedications (drugs) used in livestock, such ascattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and poultry, are regulatedby the FDA because they are used in animals thatwill enter the human food supply. It’s that simple.The Young Farmers and Ranchers program alsosponsors scholarships for deserving students.7

MBA Officers and At-Large Directors 2015President – Austin Smith (601.408.5465); Vice President – Johnny Thompson (601.656.5701); Treasurer – Stan Yeagley (601.924.2582); Secretary –Cheryl Yeagley (601.924.2582); At-Large Director – Harvey Powell, Jr. (203.565.7547); At-Large Director – Milton Henderson (601.763.6687); andAt-Large Director – John R. Tullos (601.782.9362)Animal drugs are available as over-the-counter(OTC), prescription (Rx), or through a veterinaryfeed directive (VFD). For prescriptions and VFDs,veterinarians are responsible for authorizing theproper medications, in a legal manner, only to thoseanimals that truly need them. In turn, producers areresponsible for the proper use and administration,according to the drug label, and documentation ofall prescription and VFD medications used in theiranimals.Dispensing, prescribing, or authorizing aprescription or VFD product requires a validveterinary-client-patient relationship (VCPR). It isillegal for a veterinarian to dispense or write aprescription or VFD for an animal/herd he/she hasnot seen or is unfamiliar with. A VCPR is importantfor both veterinarians and livestock producersbecause it communicates a type of “agreement”between parties on the responsibility and care forthe animals. Under the guidelines of the FDAAnimal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act(AMDUCA), a VCPR exists when all of thefollowing conditions are met (Title 21, Code ofFederal Regulations, Part 530 or 21 CFR 530): The veterinarian has assumed responsibility formaking clinical judgments regarding the health ofthe animal/herd and the need for medical treatment,AND the client has agreed to follow his/herdirections. There is sufficient knowledge of the animal(s) bythe veterinarian to initiate at least a general orpreliminary diagnosis of the medical condition ofthe animal(s). The veterinarian is readily available for follow-upin case of adverse reactions or failure of theregimen of therapy. Such a relationship can existonly when the veterinarian has recently seen and ispersonally acquainted with the keeping and care ofthe animal(s) by virtue of examination of theanimal(s), and/or by medically appropriate andtimely visits to the premises where the animal(s) arekept.Drugs used in food animals must be used accordingto their labeled directions, unless the veterinarianfeels that an extra-label drug use (ELDU) isindicated. The FDA allows ELDU only under thecontext of an established VCPR, and only withproducts that are not prohibited for ELDU. Extralabel drug use means the “actual use or intended useof a drug in an animal in a manner that is not inaccordance with the approved labeling. Thisincludes, but is not limited to, use in species notlisted in the labeling; use for indications (disease orother conditions) not listed in the labeling; use atdosage levels, frequencies, or routes ofadministration other than those stated in thelabeling; and deviation from the labeled withdrawaltime based on these different uses” (21 CFR 530). Acurrent list of drugs prohibited from ELDU can befound at www.fda.gov or www.farad.org.Rules regarding ELDU apply to both OTC andprescription products. This is an area that is oftenmisunderstood: both OTC and prescriptionproducts require veterinary oversight to be used inan extra-label manner. In other words, just becauseyou can purchase a product without a prescriptiondoesn’t mean you can use it any way you’d like.Withdrawal times for extra-label use of any product,as well as use according to the label, must beprovided by the veterinarian. Medication deliveredin feed can only be used according to the label.Extra-label use of medication in feed is strictlyprohibited and has been for many years.Veterinarians cannot legally prescribe the use ofany feed additive

Friday. Giving away door prizes is a way to spice up a meeting. We also seek items that could be used in a silent auction. We encourage you to bring items for the silent auction related to beekeeping (even ones you no longer use but are still in good condit

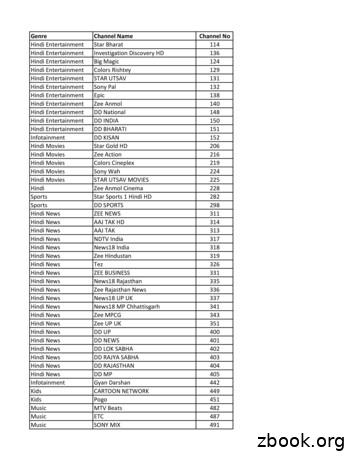

Hindi News NDTV India 317 Hindi News TV9 Bharatvarsh 320 Hindi News News Nation 321 Hindi News INDIA NEWS NEW 322 Hindi News R Bharat 323. Hindi News News World India 324 Hindi News News 24 325 Hindi News Surya Samachar 328 Hindi News Sahara Samay 330 Hindi News Sahara Samay Rajasthan 332 . Nor

your classroom bee. If you would like to be well prepared for a school spelling bee, ask your teacher for the 450-word School Spelling Bee Study List, which includes the words listed here in addition to the words at the Two Bee and Three Bee levels of difficulty. 25. admit (verb) to accept as the truth. 26.

To the 4-H Leader: The honey bee project (Books 1 - 4) is intended to teach young people the basic biology and behavior of honey bees in addition to hands-on beekeeping management skills. The honey bee project books begin with basic honey bee and insect information (junior level) and advance to instruction on how to rear honey bee colonies and

81 news nation news hindi 82 news 24 news hindi 83 ndtv india news hindi 84 khabar fast news hindi 85 khabrein abhi tak news hindi . 101 news x news english 102 cnn news english 103 bbc world news news english . 257 north east live news assamese 258 prag

Baby Bumble Bee I’m bringing home a baby bumble bee Won’t my mommy be so proud of me I’m bringing home a baby bumble bee OUCH! It stung me I’m squishing up my baby bumblebee Won’t my mommy be so proud of me I’m squishing up my baby bumble bee Eww, it’s yucky I’m licking up my baby bumble bee Won’t my mommy be so proud of me

Wild honey bees (also called Africanized bees) in Arizona are a hybrid of the western honey bee (Apis mellifera), and other bee subspecies including the East African lowland honey bee (Apis mellifera scutellata), the Italian honey bee . Apis mellifera ligustica, and the Iberian honey bee . Apis mellifera iberiensis. They sometimes establish colonies

School Spelling Bee The School Spelling Bee coordinator directs the School Spelling Bee. This Bee may be held during school hours or in the evening. An area with a stage and good lighting is best, although libraries are quite fitting places. You may want to video tape the performance. A word of caution

multiplication of bee colonies through Master Trainers. 6. Distribution of bee boxes with bee colonies and tool kits:- The field offices have distributed the bee boxes with live bee colonies and other tool kits to the trained beneficiaries, as per the targets allocated to them, So as to start practically the beekeeping activity at their places. 7.