OIG-18-67 - ICE's Inspections And Monitoring Of Detention .

ICE’s Inspections andMonitoring of DetentionFacilities Do Not Lead toSustained Compliance orSystemic ImprovementsJune 26, 2018OIG-18-67

DHS OIG HIGHLIGHTSICE’s Inspections and Monitoring ofDetention Facilities Do Not Lead to SustainedCompliance or Systemic Improvements June 26, 2018What We FoundWhy WeDid ThisInspectionICE uses two inspection types to examinedetention conditions in more than 200 detentionfacilities. ICE contracts with a private companyand also relies on its Office of Detention Oversightfor inspections. ICE also uses an onsitemonitoring program. Yet, neither the inspectionsnor the onsite monitoring ensure consistentcompliance with detention standards, nor do theypromote comprehensive deficiency corrections.Specifically, the scope of ICE’s contractedinspections is too broad; ICE’s guidance onprocedures is unclear; and the contractor’sinspection practices are not consistentlythorough. As a result, the inspections do not fullyexamine actual conditions or identify alldeficiencies. In contrast, ICE’s Office of DetentionOversight uses effective practices to thoroughlyinspect facilities and identify deficiencies, butthese inspections are too infrequent to ensure thefacilities implement all deficiency corrections.Moreover, ICE does not adequately follow up onidentified deficiencies or consistently holdfacilities accountable for correcting them, whichfurther diminishes the usefulness of inspections.Although ICE’s inspections, follow-up processes,and onsite monitoring of facilities help correctsome deficiencies, they do not ensure adequateoversight or systemic improvements in detentionconditions, with some deficiencies remainingunaddressed for years.U.S. Immigration andCustoms Enforcement(ICE) inspects andmonitors just over 200detention facilitieswhere removable aliensare held. In this reviewwe sought to determinewhether ICE’simmigration detentioninspections ensureadequate oversight andcompliance withdetention standards. Wealso evaluated whetherICE’s post-inspectionfollow-up processesresult in correction ofidentified deficiencies.What WeRecommendWe made fiverecommendations toimprove inspections,follow-up, andmonitoring of ICEdetention facilities.For Further Information:Contact our Office of Public Affairsat (202) 254-4100, or email us atDHS-OIG.OfficePublicAffairs@oig.dhs.govICE ResponseICE officials concurred with all fiverecommendations and proposed steps to updateprocesses and guidance to improve oversight overdetention facilities.www.oig.dhs.govOIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland SecurityWashington, DC 20528 / www.oig.dhs.gov-XQH MEMORANDUM FOR:Thomas D. HomanDeputy Director and Senior Official Performing theDuties of the DirectorU.S. Immigration and Customs EnforcementFROM:John V. KellyActing Inspector GeneralSUBJECT:ICE’s Inspections and Monitoring of Detention FacilitiesDo Not Lead to Sustained Compliance or SystemicImprovementsAttached for your information is our final report, ICE’s Inspections andMonitoring of Detention Facilities Do Not Lead to Sustained Compliance orSystemic Improvements. We incorporated the formal comments from the ICEOffice of Custody Management and Office of Detention Oversight in the finalreport.Consistent with our responsibility under the Inspector General Act, we willprovide copies of our report to congressional committees with oversight andappropriation responsibility over the Department of Homeland Security. We willpost the report on our website for public dissemination.Please call me with any questions, or your staff may contact Jennifer Costello,Chief Operating Officer, at (202) 254-4100.Attachment

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security Table of Contents Background . 1Results of Inspection. 4Nakamoto Inspections Are Significantly Limited and Office of DetentionOversight Inspections Are Not Frequent Enough . 5Inadequate Inspection Follow-up Leads to Continuing Deficiencies . 11Onsite Detention Service Managers Face Challenges in ImprovingCompliance . 14Conclusion . 15Recommendations. 15AppendixesAppendix A: Objective, Scope, and Methodology . 19Appendix B: Management Comments to the Draft Report . 20Appendix C: National Detention Standards (NDS) andPerformance-Based National Detention Standards(PBNDS 2008 and PBNDS 2011) . 24Appendix D: Core Standards ICE Office of Professional Responsibility’sOffice of Detention Oversight Uses to Assess Detention Conditions . 26Appendix E: Office of Inspections and Evaluations MajorContributors to This Report . . 27Appendix F: Report Distribution. . DSwww.oig.dhs.gov average daily populationDetention Standards and Compliance UnitDetention Service ManagerEnforcement and Removal OperationsField Office DirectorU.S. Immigration and Customs EnforcementInter-governmental Service AgreementNational Detention StandardsOffice of Detention OversightOffice of Inspector GeneralPerformance-Based National Detention StandardsOIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security SOWUCAPwww.oig.dhs.gov Statement of WorkUniform Corrective Action PlanOIG-18-67

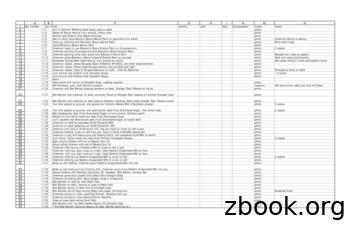

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security BackgroundU.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Enforcement and RemovalOperations (ERO) apprehends removable aliens, detains these individuals whennecessary, and removes them from the United States. All ICE detainees areheld in civil, not criminal, custody. ICE detention is administrative in nature,aimed to process and prepare detainees for removal. At the end of fiscal year2017, ICE held nearly 38,000 detainees in custody, with more than 35,000detainees in the facilities that undergo ICE inspections discussed in this report.Table 1 lists the types and numbers of facilities ICE uses to detain removablealiens as well as the average daily population (ADP) at the end of FY 2017.Table 1: Types of Facilities ICE Uses for DetentionFacility TypeDescriptionNumber ofFacilitiesFY 17 YearEnd ADPService ProcessingCenter(SPC)Facilities owned by theDepartment of HomelandSecurity and generally operatedby contract detention staff53,26386,818Contract Detention Facilities owned and operatedby private companies andFacilitycontracted directly by ilities, such as local and countyjails, housing ICE detainees (as wellas other inmates) under an IGSAwith ICE878,778Dedicated IntergovernmentalServiceAgreement(DIGSA)Facilities dedicated to housingonly ICE detainees under an IGSAwith ICE119,820U.S. MarshalsService IntergovernmentalAgreement(USMS IGA)Facilities contracted by the U.S.Marshals Service that ICE alsoagrees to use1006,75621135,435Total:Source: ICE datawww.oig.dhs.gov 1OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security ICE began operating its detention system under the National DetentionStandards (NDS), which it issued in 2000 to establish consistent conditions ofconfinement, program operations, and management expectations in itsdetention system. Along with stakeholders, ICE revised the NDS and developedPerformance-Based National Detention Standards 2008 (PBNDS 2008) toimprove safety, security, and conditions of confinement for detainees. With itsPerformance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 (PBNDS 2011), ICEaimed to enhance immigration detention conditions while maintaining a safeand secure detention environment for staff and detainees. Contracts andagreements with facilities that hold ICE detainees include either NDS, PBNDS2008, or PBNDS 2011.1 Appendix C lists the standards included in each set.As part of its layered approach, various ICE offices manage the oversight andmonitoring of detention standards and have different roles and responsibilities.Specifically, ICE uses the following inspections2 and onsite monitoring programto determine whether facilities comply with applicable detention standards.3x Inspections by Nakamoto Group, Inc. (Nakamoto): ICE ERO CustodyManagement, which manages ICE detention operations and oversees theadministrative custody of detained aliens, contracts with Nakamoto4 toannually or biennially inspect facilities that hold ICE detainees more than72 hours.5 Nakamoto inspects about 100 facilities per year to determinecompliance with 39 to 42 applicable detention standards.6 Nakamotoinspected or re-inspected 103 facilities in 2015, 83 facilities in 2016, and116 facilities in 2017. ICE uses Nakamoto to inspect all types of facilitieslisted in table 1. ICE also uses Family Residential Standards for Family Residential Centers holding familiesand juveniles; we did not examine oversight of these facilities in this review.2 The inspection types evaluated in this report inspect facilities holding detainees more than 72hours because about 99 percent of ICE detainees are in such facilities. 3 ICE also has procedures for operational review self-assessments, which allow facilities withan average daily population of fewer than 10 detainees or those designated as short-termfacilities that house detainees under 72 hours to conduct their own inspections, under theguidance of the local ICE ERO field office. We did not assess these operational review selfassessments.4 ICE ERO has been contracting with Nakamoto since 2007; ICE ERO last re-competed and reawarded the contract in 2016.5 Nakamoto also conducts quality assurance reviews, technical assistance reviews, follow-upinspections, special assessments, and pre-occupancy inspections; we only assessedNakamoto’s annual/biennial inspections. Nakamoto also inspects a few facilities holdingdetainees less than 72 hours. 6 As shown in appendix C, the number of standards inspected depends on whether the facilityoperates under NDS or PBNDS.1www.oig.dhs.gov 2OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security x Inspections by the Office of Detention Oversight (ODO): ODO is unit ofthe ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility, Inspections and DetentionOversight Division. ODO is institutionally separate from ERO. As such, ODOinspections aim to provide ICE executive leadership with an independentassessment of detention facilities. About once every 3 years, ODO alsoinspects detention facilities that hold ICE detainees more than 72 hours(and have an average daily population of more than 10 detainees). ODOadjusts its inspection schedule based on perceived risk, ICE direction, ornational interest. ODO leadership determines the facilities to review eachyear based on staffing budget, agency priorities, and special requests by ICEleadership. Contract staff from Creative Corrections, LLC support ODOteams. ODO inspects facilities to determine compliance with 15 to 16 “core”standards, identified in appendix D. ODO inspected 23 facilities in FY 2015,29 in FY 2016, and 33 in FY 2017. ODO also inspects all types of facilitieslisted in table 1, but less frequently.x Monitoring by the Detention Service Managers (DSM): ICE ERO CustodyManagement also has a Detention Monitoring Program through which onsiteDSMs at select facilities, covering each facility type listed in table 1,continuously monitor compliance with ICE detention standards. InDecember 2017, 35 DSMs monitored compliance with ICE detentionstandards at 54 facilities holding more than 70 percent of detainees. BothNakamoto and ODO still inspect facilities that have DSMs as the inspectionprocesses are separate from the onsite monitoring.The responsibility for monitoring follow-up and corrective actions resultingfrom ICE’s detention oversight falls to the Detention Standards and ComplianceUnit (DSCU), also within ICE ERO Custody Management, and to ICE ERO fieldoffices. Detention facilities develop Uniform Corrective Action Plans (UCAP)when either Nakamoto or ODO inspections find instances of noncompliance.DSCU and ICE ERO field office managers work with facilities to resolve theissues.We evaluated policies, procedures, and inspection practices, and we observedNakamoto and ODO inspections of detention facilities. Between April andAugust 2017, we observed Nakamoto inspections at Irwin County DetentionCenter in Ocilla, Georgia, and at Johnson County Detention Center inCleburne, Texas. We observed ODO inspections at Eloy Detention Center inEloy, Arizona, and at Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia. We alsoreviewed a sample of Nakamoto and ODO inspection reports and UCAPs toevaluate how ICE reports on and corrects identified deficiencies. For ourobservations, we used a limited judgmental sample and relied on ourwww.oig.dhs.gov 3OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security professional judgment as inspectors to draw conclusions when we observedpractices of Nakamoto and ODO inspection teams. We also interviewed nineDSMs from various types of facilities. In this review we sought to determine theeffectiveness of both ICE’s immigration detention inspection and follow-upprocesses as well as its monitoring of detention facilities.Results of InspectionNeither type of inspection ICE uses to examine detention facilities ensuresconsistent compliance with detention standards or comprehensive correction ofidentified deficiencies. Specifically, because the Nakamoto inspection scope istoo broad, ICE’s guidance on procedures is unclear, and Nakamoto’s inspectionpractices are not consistently thorough, its inspections do not fully examineactual conditions or identify all compliance deficiencies. In contrast, ODO useseffective methods and processes to thoroughly inspect facilities and identifydeficiencies, but the inspections are too infrequent to ensure the facilitiesimplement all corrections. Moreover, ICE does not adequately follow up onidentified deficiencies or systematically hold facilities accountable for correctingdeficiencies, which further diminishes the usefulness of both Nakamoto andODO inspections. In addition, ICE ERO field offices’ engagement with onsiteDSMs is inconsistent, which hinders implementation of needed changes.Although ICE’s inspections, follow-up processes, and DSMs’ monitoring offacilities help correct some deficiencies, they do not ensure adequate oversightor systemic improvements in detention conditions; certain deficiencies remainunaddressed for years.As some of our previous work indicates, ICE’s difficulties with monitoring andenforcing compliance with detention standards stretch back many years andcontinue today. In 2006, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) identified issuesrelated to ICE detention facility inspections and implementation of correctiveactions. In our 2006 report, we recommended that ICE “improve the inspectionprocess and ensure that all non-compliance deficiencies are identified andcorrected.”7 In a December 2017 report, which related to OIG’s unannounced Treatment of Immigration Detainees Housed at Immigration and Customs EnforcementFacilities, OIG-07-01, December 20067www.oig.dhs.gov 4OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security inspections of five detention facilities, we identified problems in some of thesame areas noted in the 2006 report.8Nakamoto Inspections Are Significantly Limited and Office ofDetention Oversight Inspections Are Not Frequent EnoughAfter observing Nakamoto and ODO inspections in detention facilities andevaluating their inspection methods, practices, and reports, we determined thatICE detention facility compliance enforcement is lacking because Nakamoto’sinspection scope is too broad; ICE does not provide clear guidance onprocedures; and the Nakamoto inspectors are not always thorough. In contrast,ODO’s inspections are better scoped and more comprehensive, but are tooinfrequent to ensure compliance and effect regular and consistent changes indetention conditions. Both sets of inspections have value, but their weaknessesrender them inadequate to promote effective oversight. In the followingparagraphs we detail the inspections’ strengths and weaknesses.Pre-inspection: ICE only requires the Nakamoto teams to review previousoversight reports and inspection results for a facility during pre-inspectionresearch. Therefore, Nakamoto inspectors typically limit their pre-inspectionresearch to reviewing previous Nakamoto inspection reports and UCAPs for theinspected facility. Prior to each inspection, according to a Nakamoto manager,an introductory letter, inspection notification letter, and a blank facilityincident form are sent to the detention facility. When applicable, the detentionfacilities complete the incident form, detailing any incident that may haveoccurred during the year between inspections.In contrast, before visiting a detention facility, ODO policies direct ODOinspection teams to research and compile information from the facility and therelevant ERO field office.9 We reviewed ODO’s pre-inspection packages, whichincluded documents from the facility and ICE ERO, such as contracts, facilityrecords, local ERO policies and procedures, complaints the ICE Joint IntakeCenter received about the facility, and any detainee death reports. The preinspection materials also included policies on emergency response, safetyinspections, and use of force. Through this research, ODO teams check forpotential deficiencies before they arrive at the facility, which allows more timeon site to assess detention conditions instead of reviewing policies andprocedures. Concerns about ICE Detainee Treatment and Care at Detention Facilities, OIG-18-32, December2017 9 ICE ERO has 24 field offices that manage detention operations in their geographic area. 8www.oig.dhs.gov 5OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security Scope: The Nakamoto inspection scope is too broad to be completed by a smallteam in a short timeframe. Under its Statement of Work (SOW) with ICE,Nakamoto must determine compliance with all 39 to 42 applicable detentionstandards by examining more than 650 elements of the standards at more than100 facilities a year. Typically, three to five inspectors have only 3 days tocomplete the inspection, interview 85 to 100 detainees, brief facility staff, andbegin writing their inspection report for ICE. Even with a full 5-memberinspection team, each of four inspectors has to evaluate compliance with about10 standards. The fifth inspector completes a Quality of Medical CareAssessment,10 when applicable, which includes using 20 checklists, eachrequiring review of 10 to 20 patient records. Nakamoto inspectors also told usthat it was difficult to complete their work in the allotted time.Under ODO’s guidance, ODO teams assess compliance with 15 or 16 “core”standards selected because deficiencies in these standards could mostsignificantly impact a detainee’s health, safety, civil rights, and civil liberties.11Hence, ODO inspections appear to be appropriately scoped for the size of theteams performing the work. A typical ODO team has six or seven inspectors,consisting of three ODO employees and three or four contractors from CreativeCorrections, LLC. Each member of the ODO team has 3 days to assesscompliance with either two or three detention standards. We observed anadequate number of ODO inspectors and contractors, who appeared to have areasonable workload and enough time to thoroughly inspect facilities, as wellas observe and validate actual detention conditions. However, although it helpsto narrow the scope, by limiting its inspections to assessing just the “core”standards, ODO is scrutinizing compliance with fewer than half of the NDS orPBNDS standards. Guidance and Inspection Practices: ICE provides Nakamoto with detentionreview summary forms and inspection checklists to determine compliance withdetention standards, but it does not give Nakamoto clear procedures forevaluating detention conditions. In general, the Nakamoto inspection practiceswe observed fell short of the SOW requirements. Specifically, we saw someinspectors observing and validating “the actual conditions at the facility,” perthe SOW, but other Nakamoto inspectors relied on brief answers from facility In 2016, ICE added a Quality of Medical Care Assessment to Nakamoto’s inspection of “over72 hour” facilities. ICE Health Service Corps and the DHS Office for Civil Rights and CivilLiberties developed a standardized quality of care audit toolkit. Most of the measures are notdetention standard requirements.11 ODO may review standards outside of the “core” standards based on conditions at the facilityor at the request of ICE leadership. Appendix D contains details on the core standards.10www.oig.dhs.gov 6OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security staff and merely reviewed written policies and procedures instead of observingand evaluating facility conditions. Some inspectors did not consistently look atdocumentation to substantiate responses from staff or ensure the facility wasactually implementing the policies and procedures.12 For example:x An inspector documented that A-files13 contained required identificationdocuments without checking the actual files.x Facility staff told inspectors that drivers had commercial driving licensesas required, but the inspectors did not review records to confirm.x An inspector encountered two detainees held in administrativesegregation14 because, according to the facility officer, they arrived late thenight before and no space was available in the general population area ofthe facility. The inspector did not follow up to ensure the placement inadministrative segregation was properly documented as required.x Some Nakamoto inspectors relied on responses from facility employees whowere not responsible for the areas and functions the inspectors wereinquiring about, such as asking a classification officer responsible foradmissions about the standards relating to Visitation and Law Library,instead of asking staff responsible for those areas.In contrast, ODO has developed clear procedures and effective tools to helpinspectors thoroughly inspect facilities. During the two inspections weobserved, each ODO inspector used the checklist to determine “line-by-line”compliance with two or three detention standards. In addition, the inspectorsdevoted most of their time to observing facility practices, validatingobservations through records review, and interviewing ICE and facilityemployees and detainees.ODO teams consistently identify more deficiencies than Nakamoto when thetwo groups inspect the same facilities. For example, in FY 2016, for the same Several ICE employees in the field and managers at ICE ERO headquarters commented thatNakamoto inspectors “breeze by the standards” and do not “have enough time to see if the[facility] is actually implementing the policies.” They also described Nakamoto inspections asbeing “very, very, very difficult to fail.” One ICE ERO official suggested these inspections are“useless.”13 A-file refers to an Alien File, a file that identifies a non-citizen by unique personal identifiercalled an Alien Registration Number. A-Files are official files for all immigration andnaturalization records.14 Detention facility staff sometimes segregate detainees from a detention facility’s generalpopulation using two types of segregation disciplinary and administrative. Although separatedfrom other detainees, detainees in segregation are permitted daily contact with detention andmedical staff, as well as time for recreation, library, and religious activities. 12www.oig.dhs.gov 7OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security 29 facilities ODO and Nakamoto inspected, ODO’s teams found 475deficiencies while Nakamoto teams reported 209 deficiencies. Given that ODOlooks at 15 to 16 standards and Nakamoto inspects 39 to 42 standards, themuch larger number of deficiencies identified by ODO is surprising.Detainee Interviews: For the two inspections we observed, Nakamoto reportedinterviewing between 85 and 100 detainees, but the interviews we saw duringthese two inspections did not comply with the SOW and we would notcharacterize them as interviews. The SOW requires detainee interviews toinclude “private conversations with individual detainees (in a confidentialarea),” but we did not see any interviews taking place in private settings.Instead, inspectors had brief, mostly group conversations with detainees intheir detention dorms or in common areas in the presence of detention facilitypersonnel, generally asking four or five basic questions about treatment, food,medical needs, and opportunities for recreation. Describing these discussionsbetween Nakamoto inspectors and detainees as “interviews” is not consistentwith the SOW requirements.The SOW also requires Nakamoto inspectors to interview detainees who do notspeak English, but we did not observe any interviews Nakamoto inspectorsconducted in a language other than English, nor any interviews in whichinspectors used available DHS translation services. In fact, inspectors selecteddetainees for interviews by first asking whether they spoke English. During oneinspection, a facility guard translated for a detainee. Inspectors did notconsistently follow up with the facility or ICE staff on issues detainees raised.Conversely, we observed ODO teams closely following ODO guidance oninterviewing a representative sample of detainees, in confidential settings, andin languages detainees understand. ODO teams used an interview form thatincluded a wide range of questions about the living conditions, safety, and wellbeing of detainees and elicited candid responses and insight on facilityconditions. According to ODO policy, depending on the size of the facility,inspectors interview between 10 and 40 detainees, including all detainees insegregation. We observed ICE ODO staff interviewing about 30 detainees oneon-one in a confidential setting, separate from facility staff and ICE employees.We also observed ODO inspectors interviewing every detainee in segregation.Inspectors selected detainees to interview based on a number of factors, suchas length of detention, age, medical history, and the detainee’s country oforigin. ODO used the DHS language telephone line for translation andinterviewed some detainees in Spanish and other languages. ODO teamsdiscussed every issue raised during these interviews with facility and ICEwww.oig.dhs.gov 8OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security officials and identified a number of deficiencies that may have gone undetectedwithout these interviews.Onsite Briefings: Both Nakamoto and ODO inspectors briefed facility staff atthe end of each day. As a result, we identified some deficiencies that werecorrected while inspectors were onsite, such as discontinuing the practice ofcharging ICE detainees for medical co-payments, requiring more privacy formedical examinations, repairing inoperable telephones, and updating facilityhandbooks. Although Nakamoto does not track such onsite corrective actions,ODO does — for example, in FY 2016, ODO recorded 106 onsite corrections to475 identified deficiencies at 29 facilities. Initiating onsite corrections is a goodpractice.Reporting: Following each inspection, Nakamoto sends ERO a completedchecklist with an assessment of each element of the evaluated standards and asummary of the inspection. We identified inaccuracies in Nakamoto’s summaryreports and checklists we selected for our sample. In some instances,Nakamoto’s reports misrepresented the level of assurance or the workperformed in evaluating the actual conditions of the facility and the informationin the reports was inconsistent with what we observed during inspections. Forexample:x Nakamoto reported “Detainees were familiar with ICE officers andunderstood how to obtain assistance from ICE officers and the casemanagers. Interviews yielded positive comments regarding access to libraryservices, access to case managers and visiting opportunities.” However, weheard detainees tell inspectors they did not know the identity of their ICEdeportation officer or how to contact the officer. We did not observeinspectors asking any detainees about law library services or visitingopportunities.x At one facility, we discovered it was impossible to dial out using any tollfree number, including the OIG Hotline number, due to telephone companyrestrictions on the facility. We alerted the facility, which started working tocorrect this facility-wide issue by modifying the directions for dialing tollfree numbers. Although the issue was not corrected until the third day ofthe inspection, a Nakamoto inspector wrote on a checklist that aninspector could reach the OIG Hotline from several units on the second dayof the inspection.x At another facility, Nakamoto inspectors questioned an ICE employeeabout the facility’s correction officer duties, instead of actually interviewingwww.oig.dhs.gov 9OIG-18-67

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security correction officers. Yet, Nakamoto insp

Management also has a Detention Monitoring Program through which onsite DSMs at select facilities, covering each facility type listed in table 1, continuously monitor compliance with ICE detention standards. In December 2017, 35 DSMs monitored compliance with ICE detention standards at 54 f

Present ICE Analysis in Environmental Document 54 Scoping Activities 55 ICE Analysis Analysis 56 ICE Analysis Conclusions 57 . Presenting the ICE Analysis 59 The ICE Analysis Presentation (Other Information) 60 Typical ICE Analysis Outline 61 ICE Analysis for Categorical Exclusions (CE) 62 STAGE III: Mitigation ICE Analysis Mitigation 47 .

The ice-storage box is the destination point where the ice will accummulate via the ice-delivery hose. An ice-level sensor installed in the storage box halts ice production when the box is full. The ice-storage box should be able to hold water and have at least 2" (51mm) of insulation to keep the ice frozen as long as

Department of Labor (DOL) is pleased to present the OIG Investigations Newsletter, containing a bimonthly summary of selected investigative accomplishments. The OIG conducts criminal, civil, and administrative investigations into alleged violations of federal laws relating to DOL programs, operations, and personnel. In addition, the OIG conducts

Here’s why: There’s a difference between sea ice and land ice. Antarctica’s land ice has been melting at an alarming rate. Sea ice is frozen, floating seawater, while land ice (called glaciers or ice sheets) is ice that’s accumulated over time on land. Overall, Antarctic sea ice has been stable (so far) — but that doesn’t contradict the

670 I ice fatete, ice-dancing tikhal parih laam le lehnak. ice-fall n a hraap zetmi vur ih khuh mi hmun, lole vur tla-ser. ice-field n vur ih khuhmi hmun kaupi. ice-floe n ti parih a phuan mi tikhal tleep: In spring the ice-floes break up. ice-free adj (of horbour) tikhal um lo. ice hockey tikhal parih hockey lehnak (hockey bawhlung fung ih thawi).

Surface Ice Rescue Student Guide Page 5 5. Thaw Hole - A vertical hole formed when surface holes melt through to the water below. 6. Ice Crack - Any fissure or break in the ice that has not caused the ice to be separated. 7. Refrozen Ice - Ice that has frozen after melting has taken place. 8. Layered Ice - Striped in appearance, it is constructed from many layers of frozen and

national ice cream competition results 2020 national ice cream champion 2020 best of flavour 2020 best of vanilla 2020 jim valenti senior shield dairy ice cream vanilla equi’s ice cream ralph jobes shield open flavour pistachio crunch luciano di meo dairy ice cream vanilla equi’s ice cream alternative class - glass trophy gold medal .

11 91 Large walrus herd on ice floe photo 11 92 Large walrus herd on ice floe photo 11 93 Large walrus herd on ice floe photo Dupe is 19.196. 2 copies 11 94 Walrus herd on ice floe photo 11 95 Two walrus on ice floe photo 11 96 Two walrus on ice floe photo 11 97 One walrus on ice floe photo