Schedule Of Events - United States Patent And Trademark

The United States Patent and Trademark Officeand The George Washington University Law SchoolpresentThe 2015 Works-in-Progress Intellectual Property ColloquiumFebruary 5–7, 2015at theUnited States Patent and Trademark OfficeMadison Building600 Dulany StreetAlexandria, VA 22314Schedule of EventsUnless otherwise noted, all events will take place on the premises of theUSPTO Global Intellectual Property Academy in the Madison Building.All participants will have to pass through a security screening and possess a valid government ID.Please allow time for the screening when planning your arrival.Thursday, February 56:30 pm – 8:30 pmFriday, February 68:00 am – 9:00 am9:00 am – 10:40 am10:40 am – 11:00 am11:00 am – 12:20 pm12:20 pm – 2:00 pm2:00 pm – 3:20 pm3:20 pm – 3:40 pm3:40 pm – 5:00 pm6:30 pmSaturday, February 78:00 am – 9:00 am9:00 am – 10:40 am10:40 am – 11:10 am11:10 am – 12:30 pm12:30 pm – 1:00 pm1:00 pm – 2:20 pmWelcome Reception at the National Inventors Hall of Fame andMuseum (Madison Building Atrium)Presentation on IP Law & Policy at the USPTO, then BreakfastFirst SessionCoffee BreakSecond SessionLunch at the Madison South Auditorium (Concourse Level)Third SessionCoffee BreakFourth SessionReception and Dinner at Il Porto, 121 King Street, Alexandria,second floor. Cash bar; wine served at dinner; music by the WIPIPAll-StarsPresentation on IP at GW Law, then BreakfastFifth SessionCoffee BreakSixth SessionNourishment BreakSeventh Session

Session 2: 11:00—12:20Session 1: 9:00—10:40Session 3: 2:00—3:20Session 4: 3:40—5:00Venice RoomDeborah Gerhardt (& Jon McClanahan), ColorsSingapore RoomxJeanne Fromer (& Barton Beebe), The Closing ofthe Linguistic Frontier in Trademark LawBerne RoomxLisa Ramsey, Trademarking Everything?Paris RoomxU. Shen Goh, Branding Linguistics: What do CocaCola and Chinese Bakeries Have in Common?Trademarkx Victoria Schwartz, Privacy Problems Start at the TopxIP and the Internetx Michael Goodman, Empirical Assessment ofJudges’ Behaviorx Joseph Mtebe Tungaraza, Cybersquatting: theRelevance of the UDRP to Developing Countriesx Sarah Rajec, Indisputable IP: Case Studiesx William Hubbard, Raising (or Razing?) the PatentBarx Lucille M. Ponte, Protecting Brand Image or Gamingthe System?x Gregory Dolin, Dubious Patent ReformAbraham Bell (& Ted Sichelman & GideonParchomovsky), Trademarks as Club Goodsx Jeremy Sheff, The Ragged Edge of the Lanham ActTrademarkx Rebecca Tushnet, Registering Discontentx Megan Carpenter, “Behind the Music”: Lanham Act2(a)x Franck Gloglo, Exceeding the National Boundaries ofIP Rights in Light of the WTOxxRebecca Curtin, The Transactional Origins ofAuthor’s CopyrightAbraham Bell (& Gideon Parchomovsky), CopyrightTrustCopyrightx Sapna Kumar, Policing Digital TradeBen Depoorter (& Alain van Hiel), The Dynamics ofCopyright Enforcementx David S. Levine, Temporal Transparency and theProcess of Intellectual Property Lawmakingx Elizabeth Winston, Patent BoundariesxElizabeth Townsend Gard (& Geena Yu), Is Fair UseCodable?x Felix Wu, Secondary Copyright Remediesx Aaron Perzanowski, Digital Property: The UncertainFuture of Ownershipx Annemarie Bridy, Aereo: From Working AroundCopyright to Thinking Inside the (Cable) Boxx Brad Greenberg, Black Box CopyrightCopyrightxInternational / Cross-Borderx Joy Y. Xiang, Addressing Climate Change: IP, No IP,or Another Possibility?x Margo Bagley, Of Indigenous Group “Straws” andDeveloped Country “Camels”: Patents, Innovation,and the Disclosure of Origin requirementx Alexandra George, Spiritual Property: IndigenousKnowledge Systems in an Intellectual PropertyEnvironmentIP and Developmentx Christine Davik, Access Granted: The Necessity of aPresumption of Public Access under the CFAA andBeyondx Scott Kieff (& Troy Paredes), Variations in InternalGovernment StructuresPatent Value / Remediesx Jonathan H. Ashtor, Redefining “Valuable Patents”x David Abrams, Patent Value and Citationsx Jonathan Masur, The Misuse of Prior Licenses inSetting Patent Damagesx Chris Seaman, Property v. Liability Rules in PatentLitigation Post E-BayPatent Presumptions / Procedurex Jeremy Bock, An Error-Cost Assessment of thePresumption of Validityx Irina D. Manta (& Gregory Dolin), TakingPresumptionsx Shubha Ghosh, What Makes a Case Exceptional?Fee Shifting as a Policy Leverx Greg Reilly, Patent Discovery: A Study in LitigationReformx Kristen Osenga, Everything I Needed to Learn AboutSSOs I Didn’t Learn in Law SchoolPatent—SSOs and Pledgesx Peter Lee, Centralization, Fragmentation andReplication in the Genomic Data CommonsBiotechx Jacob S. Sherkow (& Henry T. Greely), The Historyof Patenting Genetic Materialx Jorge Contreras, Patent Pledgesx Jurgita Randakeviciute , The Role of StandardSetting Organizations With Regard to BalancingRightsx Saurabh Vishnubhakat (& Arti Rai & BhavenSampat), The Rise of Bioinformatics Examination atthe Patent OfficexPatent Institutions / Policymakingx Gregory Mandel (& Kristina Olson & Anne Fast),What People Think, Know, and Think They KnowAbout IPx Jessica Silbey, IP and Constitutional Equalityx Ari Waldman, Trust: The Distinction Between thePrivate and the Public in IP Lawx Mark Lemley (& Mark McKenna), ScopeCross-IPx Prof. Dr.-Ing. Sigram Schindler, Quantification ofInventive Conceptsx Oskar Liivak, The Unresolved Ambiguity of PatentClaimsx Joseph Scott Miller, Reasonably Certain Noticex Adam Mossoff, O’Reilly v. MorsePatent—Claimsx Stefania Fusco, The Venetian Republic’s Tailoring ofPatent Protection to the Characteristics of theInventionx Dmitry Karshtedt, The Completeness Requirement inPatent Lawx Shubha Ghosh, Demarcating Nature After Myriadx Christopher Cotropia, USPTO’s Patentable SubjectMatter Analysis After AlicePatent—Subject-Matterx Jay P. Kesan (& Hsian-shan Yang), A ComparativeEmpirical Analysis of Patent Prosecution in theUSPTO and EPOx Michael Frakes (& Melissa Wasserman), Does theUS Patent & Trademark Office Grant Too ManyPatents?x Melissa Wasserman (& Michael Frakes), Is the TimeAllocated to Review Patent Applications InducingExaminers to Grant Invalid Patents?x Christopher Funk, Patent Prosecution Bars As aGeneral Rulex Bryan Choi, Separating Patent-Able from Patent ActPatent—PTOWorks-in-Progress Intellectual Property (WIPIP) 2015: Schedule of Presentations as of 2/3/2015FRIDAY, February 6, 2015

Session 5: 9:00—10:40Session 6: 11:10—12:30Session 7: 1:00—2:20Venice RoomKevin Collins, Justifying Patent Ineligibility:Regulation-Resistant Technologiesx Patrick Goold, IP Law and the Bundle of Tortsx Guy Rub, Copyright and Contracts Meet andConflictx Betsy Rosenblatt, IP, Creativity, and a Sense ofBelongingx D.R. Jones, Libraries, Contract and Copyrightx Deming Liu, Time to Rethink Copyright forEducationCopyrightx Amanda Reid, Notice of Continuing Interest in aCopyrighted Workx Robert Brauneis (& Dotan Oliar), The ElectronicCopyright Office Catalog, 1978-Presentx Chris Hubbles, No Country for Old Audiox Andres Sawicki, Law and Informal Rules of CreativeCollaborationx Peter Yu, The Copy in Copyrightx Kate Klonick, Comparing Apples to Applejacks:Cognitive Science Concepts of Similarity Judgmentx James Grimmelmann, Copyright for Literate RobotsCopyrightx Zvi Rosen, Paradoxes and Lessons of State LawProtection for Sound Recordingsx Peter J. Karol, An Exclusive Right to JudicialDiscretion: Learning from eBay’s Muddled Extensionto Trademark Lawx Xiyin Tang, The Case for Genericide Defenses inArtistic Worksx William McGeveran, What Campbell Can (and Can’t)Teach Trademark Lawx Leah Chan Grinvald, Contracting Trademark FameTrademarkx David Welkowitz, Willfulnessx Glynn Lunney, Inefficient Trademark LawTrademarkx Irina D. Manta (and Robert E. Wagner), IPInfringement as Vandalismx Jim Gibson, Copyright Incentives in the CourtroomSingapore Roomx Rachel Sachs, Innovation Law and Policy: Preservingthe Future of Personalized MedicinexYaniv Heled, Five Years to the Biologics PriceCompetition and Innovation Actx Clark D. Asay, Intellectual Property LawHybridizationBerne Roomx Ofer Tur-Sinai, Patents, Well-Being, and the State’sRole in Directing InnovationParis RoomDavid Schwartz (& Christopher Cotropia & Jay Kesan),Patent Assertion Entity (PAE) Lawsuitsx Lucas Osborn (and Joshua M. Pearce), A NewPatent System for a New Age of InnovationCopyrightxNicole Shanahan, How Data Liberation Will Nix theProverbial Patent Trollx Srividhya Ragavan, Reorienting Patents as theProtagonist for the Progress of Useful ArtsCross-IPxPaul R. Gugliuzza, Patent Trolls, Preemption, andPetitioning Immunityx Stephanie Bair, The Psychology of Innovation andTheories of Patent ProtectionPatent—RationalesxRoger Ford, the Uneasy Case for State Anti-PatentLawsx Scott Kominers (& Lauren Cohen), Patent TrollEvidence from Targeted Firmsx Ted Sichelman (& Jonathan Barnett), RevisitingLabor Mobility in Innovation MarketsPatent—Innovation Policyx Michael Burstein, Secondary Markets for Patents: AnEvaluationx Xuan-Thao Nguyen, Financing Innovation: LegalDevelopment of IP as Collateral in Financingx Sarah Burstein, The High Cost of Cheap DesignRightsx Camilla Hrdy, Patent Nationally, Innovate LocallyxNicholson Price (& Arti Rai), Biosimilars andManufacturing Trade SecretsBiotechx Cynthia Ho, Drug Rehab: How Cognitive Biases canImprove Drug DevelopmentxLiza Vertinsky, The State as PharmaceuticalEntrepreneurx Josh Sarnoff (& Alan Marco), Is Refiling Practice DoingWhat It Ought To? I Can Name That Invention in XWordsx Megan La Belle, Public Enforcement of Patent LawxPatent Institutions / Policymakingx Shawn Miller (& Ted Sichelman), Does PatentLitigation Diminish R&D?Patent—NPEsxPatent—NPEsWorks-in-Progress Intellectual Property (WIPIP) 2015: Schedule of Presentations as of 2/3/2015SATURDAY, February 7, 2015

2015 WORKS-IN-PROGRESS IP COLLOQUIUM ABSTRACTSFriday, February 6, 2015, Session 1: 9:00–10:40 . 2Patent—PTO . 2Patent Institutions / Policymaking . 6IP and the Internet . 8Trademark . 10Friday, February 6, 2015, Session 2: 11:00–12:20 . 14Patent—Subject Matter . 14Patent Value / Remedies . 16IP and Development. 18Trademark . 19Friday, February 6, 2015, Session 3: 2:00–3:20 . 23Patent—Claims . 23Patent Presumptions / Procedure . 25International / Cross-Border . 27Copyright . 29Friday, February 6, 2015, Session 4: 3:40–5:00 . 31Cross-IP . 31Biotech . 35Patent—SSOs and Pledges . 37Copyright . 38Saturday, February 7, 2015, Session 1: 9:00–10:40 . 42Patent—NPEs . 42Patent—Rationales. 43Cross-IP . 46Copyright . 47Saturday, February 7, 2015, Session 2: 11:10–12:30 . 50Patent—NPEs . 50Patent—Innovation Policy . 51Trademark . 55Copyright . 57Saturday, February 7, 2015, Session 3: 1:00–2:20 . 59Patent Institutions / Policymaking . 59Biotech . 62Trademark . 64Copyright . 661

Friday, February 6, 2015, Session 1: 9:00–10:40Patent—PTO Jay P. Kesan (& Hsian-shan Yang), A Comparative Empirical Analysis of PatentProsecution in the USPTO and EPOThe U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s 21st Century Strategic Plan presents asubstantial reform of the current patent prosecution system. Two major concerns areefficiency and quality, and the USPTO is criticized in taking too long to process patentapplications and having examiners who make too many errors in the prosecutionprocess. Comparative studies have been undertaken to learn the differences inprocedural efficiency and quality of patent examination among important internationalpatent offices to derive lessons for examiners and prosecutors.We analyze the duration and outcomes of patent examination at the United States Patentand Trademark Office (USPTO) and the European Patent Office (EPO) by utilizing amatched data set (same underlying invention and originating from the US and fromEurope) covering a sample of 34,904 applications filed during 2002 and 2008, fromwhich patents were issued by both the USPTO and the EPO. Focusing on pendency andthe differences in issued claims, our empirical findings show that the duration of patentexamination is related to the patentee’s characteristics, patent value, and its country ofpriority. Our results suggest that a patent originating from the U.S. has significantlybetter procedural efficiency at both the USPTO and the EPO. Michael Frakes (& Melissa Wasserman), Does the US Patent & Trademark OfficeGrant Too Many Patents?Many believe the root cause of the patent system’s dysfunction is that the U.S. Patent &Trademark Office (PTO or Agency) is issuing too many invalid patents that unnecessarilydrain consumer welfare. Concerns regarding the Agency’s over-granting tendencies haverecently spurred the Supreme Court to take a renewed interest in substantive patent lawand have driven Congress to enact the first major patent reform act in over sixty years.Policymakers, however, have been modifying the system in an effort to increase patentquality in the dark. As there exists little to no compelling empirical evidence the PTO isactually over granting patents, lawmakers are left trying to fix the patent system withouteven understanding the root causes of the system’s shortcomings.This Article begins to rectify this deficiency, advancing the conversation along twodimensions. First, it provides a novel theoretical source for a granting bias on the part ofthe Agency, positing that the inability of the PTO to finally reject a patent applicationmay create an incentive for the resource-constrained Agency to allow additional patents.Second, this Article attempts to explore, through a sophisticated natural-experimentframework, whether the Agency is in fact acting on this incentive and over grantingpatents. Our findings suggest that the PTO is biased towards allowing patents. Moreover,our results suggest the PTO is targeting its over-granting tendencies towards thosepatents it stands to benefit from the most—i.e., those patent applications directed towards2

technologies that have historically had high-repeat filing rates such as information,computer, and health-related technologies. Our findings provide policymakers with muchneeded evidence that the PTO is indeed over granting patents. Our results also suggestthat the literature has overlooked a substantial source of Agency bias and hence recentfixes to improve patent quality will not achieve their desired outcome of extinguishing thePTO’s over-granting proclivities. Melissa Wasserman (& Michael Frakes), Is the Time Allocated to Review PatentApplications Inducing Examiners to Grant Invalid Patents?We explore how examiner behavior is altered by the time allocated for reviewing patentapplications. Insufficient examination time may crowd out examiner search and rejectionefforts, leaving examiners more inclined to grant otherwise invalid applications. To testthis prediction, we use application-level data to trace the behavior of individualexaminers over the course of a series of promotions that carry with them reductions inexamination-time allocations. We find evidence demonstrating that the promotions ofinterest are associated with reductions in examination scrutiny and increases in grantingtendencies. Our findings imply that if all examiners were given the same time to reviewapplications as is extended to those examiners with the most generous time allocations,the Patent Office would grant nearly 20 percent fewer patents. Moreover, we findevidence suggesting that those additional patents being issued on the margin as a resultof such time pressures are of below-average levels of quality. Christopher Funk, Patent Prosecution Bars As a General RuleIn some patent cases, one party’s outside attorneys may view the other’s confidentialtechnology while drafting or amending patent claims before the Patent Office in the sametechnological field. Without proper safeguards, these attorneys could abuse theirprotected access to that confidential technology by targeting and patenting it with thevery claims they are drafting. Courts frequently protect against this danger by includinga patent prosecution bar in a protective order. A patent prosecution bar prohibits thosewho access the opposing party’s confidential technology from prosecuting patents thatcover that same technology. But many courts refuse to enter patent prosecution bars,leaving litigants’ confidential technology vulnerable to misuse.While these bars are procedural and often handled by magistrate judges, disputes overthem can erupt into satellite litigation. One party wants to forbid the other’s attorneysand experts from targeting its confidential technology with new patent claims. The otherparty wants to ensure that the attorneys and experts most familiar with its technology andpatents represent the party before the Patent Office. With weighty interests on both sides,district courts have taken conflicting approaches to prosecution bars. Before a recentdecision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, some district courts heldthat those who prosecuted patents were always making competitive decisions for theirclient and those decisions justified a prosecution bar. Other district courts held thatprosecuting patents did not necessarily involve competitive decisions and that the needfor a prosecution bar depended on the unique facts of each case.3

To settle these differences, the Federal Circuit took up a petition for mandamus relief inIn re Deutsche Bank Trust Company Americas, 605 F.3d 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2010). In thatcase, the Federal Circuit rejected the view that patent prosecution always involvedcompetitive decisions and that prosecution bars should be routinely entered. Instead, theappellate court charged district courts to evaluate the activities of each attorney todecide if his or her record showed a history of making competitive decisions inprosecution. If the moving party demonstrated such a history, then the district court mustbalance the risk that the attorney would misuse the producing party’s confidentialinformation in prosecution against the receiving party’s choice of counsel and thatcounsel’s prior work for the client. Only after balancing may the district court enter aprosecution bar. And if the moving party could not show the other side’s attorney had ahistory of competitive decisionmaking, the Federal Circuit opined that a prosecution barwas unnecessary.Deutsche Bank resolved one split among the district courts, but it created andperpetuated others. District courts have split over what Deutsche Bank requires a partyto show to justify a prosecution bar. Some courts have held that a party must show thateach attorney’s prosecution activities justify a bar. Others have held that the movingparty must show only that the proposed prosecution bar is reasonable and that theopposing party must show that an individual attorney’s activities justify an exemption tothe bar. Both before and after Deutsche Bank, district courts have split over whether aprosecution bar should cover post-grant proceedings in the Patent Office that test thevalidity of a previously issued patent and permit amendments to that patent. In mostcases, the post-grant proceeding concerns the asserted patent that the attorneys andexperts are comparing to the other side’s confidential technology. Some district courtssay a prosecution bar should always cover post-grant proceedings, some say it shouldnever cover them, and others say it should cover them unless the accused infringerinitiated the proceeding. Deutsche Bank also created a loophole for litigants seeking toavoid prosecution bars by suggesting that bars should apply only to those attorneys thatthe moving party can show has made competitive decisions in prosecution. Accordingly,district courts often reject prosecution bars for attorneys or experts with little or norecord of prosecuting patents, leaving them seemingly free to view the opposing party’sconfidential technology and advise others on how to draft a patent that targets thattechnology.Deutsche Bank has proved unworkable. To resolve the district courts’ splits and closethe loophole, the Federal Circuit should abandon its balancing test and focus on counselby-counsel analysis. Instead, the court should adopt a general rule barring parties’representatives who access the opposing party’s confidential technology from performingprosecution activities that trigger the memory of that technology and present anopportunity to patent the same. Those risky prosecution activities include determiningthe type and scope of patent protection worth pursuing, drafting or reviewing patentapplications, and drafting or amending claims during an original prosecution or postgrant proceeding. The bar on these activities should extend to prosecuting patents thatcover the same subject matter of the patents-in-suit and the confidential technologicalinformation produced in litigation.4

District courts need not wait until the Federal Circuit resolves these splits or addressesthe loophole in its jurisprudence. As the U.S. District Court for the Northern District ofCalifornia has done, district courts can adopt a model protective order for patent casesthat bars risky prosecution activities. By treating the model protective order aspresumptively reasonable, district courts can effectively run an end-around DeutscheBank to have a functional patent prosecution bar.Litigants may decry that such a general rule or model prosecution bar violates their rightto choice of counsel in a patent suit or before the Patent Office. That is incorrect. Noparty has a right to an attorney positioned to use the confidential information of theopposing party learned in one proceeding against that party in another. The lawgenerally places strict limitations on attorneys positioned to misuse another party’sconfidential information. For example, courts typically forbid an attorney fromrepresenting a client when the matter positions that attorney to use confidentialinformation from a former client in a way that harms the former client. That sameprinciple should govern prosecution bars to ensure one litigant’s representatives do notincorporate the other’s confidential ideas and technology in a patent and use the sameagainst the other party in a patent suit. Bryan Choi, Separating Patent-Able from Patent ActThe patentable subject matter doctrine is a cornerstone of patent law, allowing courts todisqualify patents as per se ineligible for protection. After decades of dormancy, thedoctrine has been abruptly revived by the Supreme Court. Caught off guard, many in thepatent community have criticized the judicial doctrine as dangerously unprincipled andhave sought to confine it to the more familiar contours of the Patent Act. Indeed,"patentable subject matter" is commonly referred to as a § 101 issue, as though it wereprincipally a matter of statutory construction.Yet, the proper understanding of the doctrine is that it constitutes independent exercise ofjudicial power separate from the Patent Act. It is a constitutional doctrine—not astatutory one—that checks legislative and executive power from exceeding theauthorization of the Progress Clause. As such, it is not a threshold "gatekeeper" inquiry,but rather a parallel inquiry that owes no fealty or deference to the Patent Act.The underlying quarrel is not that the patentable subject matter doctrine leads to badoutcomes, but the fact that it disrupts settled assumptions regarding the supremacy of thePatent Act. Those who have come to rely on the Patent Act as the first and final arbiter ofpatent policy have good reason to find the patentable subject matter doctrine unsettling.It restores an uninvited variable to the system: independent judicial authority to policepatent policy, not just rubberstamp it.5

Patent Institutions / Policymaking Sarah Rajec, Indisputable IP: Case StudiesThe adversarial process is used to adjudicate the content and boundaries of rights in UScourts and some administrative agencies. In a typical patent case, for example, the courthears arguments from opposing sides from which it can base determinations of patentvalidity and scope, infringement, and remedies. In previous work, I described how in atribunal of steadily growing importance for intellectual property disputes—TheInternational Trade Commission (“ITC” or “Commission”)—certain cases proceedwithout the benefit of participation from “both” sides. The procedures governinginvestigations at the Commission may allow a patent holder to argue its preferred claimconstruction, unopposed, and obtain an in rem, general exclusion order. Subsequently, inchallenges to Customs enforcement of Commission exclusion orders, an importer maymake arguments about infringement and previously undecided claim construction issues,also unopposed. This phenomenon is troubling for its injustice, inefficiency, and potentialfor incorrect decisions that have effects beyond the relevant parties. The nature ofintellectual property law is that incorrect decisions relating to claim scope may constrainfuture innovators and harm consumer access interests.This article examines a number of International Trade Commission investigations thatresulted in the in rem remedy of a general exclusion order to determine the strength ofthese critiques. In particular, this article focuses on investigations where all namedrespondents have been dismissed by the time the exclusion order issues, whether bysettlement, consent order, or default. In addition, the article assesses the timing of theinvestigations and the depth of the claim construction orders and the need for furtherclaim construction at Customs, and outcomes of parallel district court proceedings. Michael Goodman, Empirical Assessment of Judges’ BehaviorPatent law, perhaps the most “specialized” area of the law, is becoming more so inrecent years. While it has long been the case that to become a patent lawyer and practicebefore the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, one must both have a particular technicalor scientific background as well as pass the rigorous patent bar, the courts whereinpatents are enforced and challenged have traditionally been the purview of generalistlawyers and judges. But even outspoken critics of the specialization of courts havegenerally agreed that in “complex areas” such as patent law, it may be useful to havespecialized courts. As a result, Congress responded to creating a specialized appellatecourt to consider patent appeals in 1982, the Federal Circuit, and began implementation,in 2011, of the Patent Pilot Program, the goal of which is to designate particular judgesto deal with patent cases at the trial level. The assumption underlying this trend towardspecialization of the courts is that judges with particular expertise wil

Manufacturing Trade Secrets Liza Vertinsky, The State as Pharmaceutical Entrepreneur Leah Chan Grinvald, Contracting Trademark Fame William McGeveran, What Campbell Can (and Can’t) Teach Trademark Law Xiyin Tang, The Case for Genericide Defenses in Artistic Works James Grimmelmann, Copyri ght for Literate Robots Kate Klonick, Comparing

PACIFIC COAST HIGHWAY P.8 United States THE ETERNAL WEST P.14 United States ROUTE 66 P.22 United States THE BLUES HIGHWAY P.24 United States THE KEYS: FLORIDA FROM ISLAND TO ISLAND P.26 United States ROUTE 550: THE MILLION DOLLAR HIGHWAY P.34 United States HAWAII: THE ROAD TO HANA P.42 United States OTHER

Index to Indiana Statistics in the Decennial Censuses Contents 3rd Census of the United States (1810) 2 4th Census of the United States (1820) 3 5th Census of the United States (1830) 4 6th Census of the United States (1840) 5 7th Census of the United States (1850) 7 8th Census of the United States (1860) 10 9th Census of the United States (1870) 17

Henry Spinelli, MD – United States Sherard A. Tatum, MD – United States Jesse A. Taylor, MD – United States Mark M. Urata, MD – United States John van Aalst, MD – United States Steven Wall, MD – United Kingdom S. Anthony Wolfe, MD – United States Vincent Yeow, MD – Singapore

Schedule 5 - Exception reporting and work schedule reviews 38 Schedule 6 - Guardian of safe working hours 45 Schedule 7 – Champion of Flexible Training 49 Schedule 8 - Private professional and fee-paying work 51 Schedule 9 - Other conditions of employment 54 Schedule 10 - Leave 57 Schedule 11 - Termination of employment 67

award, now that the construction schedule may soon become a contract document in Nigeria, Quantity Surveyors should develop competencies to be able to evaluate the contractor's schedule and recommend appropriate contractor for the award. KEYWORDS: Schedule evaluation, Schedule quality, Schedule conformance scoring, Quantity Surveyors

INDICATORS OF FAECAL POLLUTION Valerie Harwood University of South Florida Tampa, United States Orin Shanks United States Environmental Protection Agency Cincinnati, United States Asja Korajkic United States Environmental Protection Agency Cincinnati, United States Matthew Verbyla San Diego State University San Diego, United States Warish Ahmed

States, the United Kingdom and France – private companies carry out the work of maintaining and modernising nuclear arsenals. This report looks at companies that are providing . Rockwell Collins (United States), TASC (United States), Textron (United States), URS (United States) PAX Chapter 4- Producers 51 Alyeska Investment Group ANZ AQR .

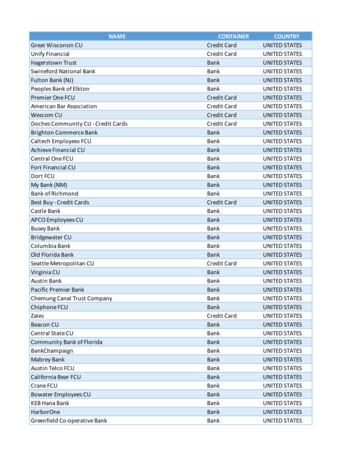

San Diego Metropolitan CU Bank UNITED STATES San Diego Metropolitan CU - Credit Cards Credit Card UNITED STATES USE CU (TX) Bank UNITED STATES . Rhodes Furniture - Credit Cards Credit Card UNITED STATES Seamans.com - Credit Cards Credit Card UNITED STATES . Cornerstone Bank (NE) Bank UNITED STATES