Breaking Bad News: A Contextual Model For Pakistan

Original ArticleBreaking Bad News:A contextual model for PakistanLubna Baig1, Sana Tanzil2, Syeda Kauser Ali3,Shiraz Shaikh4, Seemin Jamali5, Mirwais Khan6ABSTRACTObjectives: The purpose of the study was to identify the sequence of violence that ensues after breaking badnews and develop a contextual model of breaking bad news and develop a model contextual for Pakistan.Methods: A qualitative exploratory study was conducted using Six FGDs and 14 IDIs with healthcare providersworking in the emergency and the obstetrics and gynecology departments of tertiary care hospitals ofKarachi, Pakistan. Data was transcribed and analyzed to identify emerging themes and subthemes usingthematic content analysis.Results: Impatience or lack of tolerance, lack of respect towards healthcare providers, unrealisticexpectations from healthcare facility or healthcare staff were identified as main reasons that provokedviolence after breaking bad news. A conceptual five step model was developed to guide communicationof bad news by the health care providers. On initial testing the model was found to be effective in deescalation of violence.Conclusion: Communication of bad news requires application of specific approaches to deal with contextualchallenges for reducing violence against healthcare.KEYWORDS: Breaking bad news, Communication, Health care providers, Violence.doi: https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.346.15663How to cite this:Baig L, Tanzil S, Ali SK, Shaikh S, Jamali S, Khan M. Breaking Bad News: A contextual model for Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci.2018;34(6):1336-1340. doi: https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.346.15663This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0),which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.1.2.3.Prof. Dr. Lubna Baig, MBBS, MPH, MMEd FCPS, PhD,Dr. Sana Tanzil, MBBS, FCPS,Dr. Syeda Kauser Ali MBBS, MHPE, PhD,Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.4.Dr. Shiraz Shaikh, MBBS, FCPS,5.Dr. Seemin Jamali, MBBS, MPH,Jinnah Post Graduate Medical Centre,Karachi Pakistan.6.Dr. Mirwais Khan, MBBS, MPH,International Committee of Red Cross,Islamabad, Pakistan.1,2,4: APPNA Institute of Public Health,Jinnah Sind Medical University,Karachi, Pakistan.Correspondence:Prof. Lubna Baig,Pro-Vice Chancellor,Dean APPNA Institute of Public Health,Jinnah Sindh Medical University,Karachi, Pakistan.Email: lubna.baig@jsmu.edu.pk***Received for Publication:May 19, 2018Revision Received:May 30, 2018Accepted for Publication:September 20, 2018Pak J Med SciNovember - December 2018INTRODUCTIONDuring past few decades Pakistan has seen anincrease in the number of incidents of violencetargeting the general population.1,2 The country hasalso observed a considerable increase in violenceagainst healthcare mostly targeting healthcareproviders (HCPs), ambulances and hospitals.3,4There is a political will to effectively reduce theseincidents not only against the healthcare providersbut also the general public.A multicenter study conducted in Karachi, in2015 found that 66% of HCPs had experienced orwitnessed at least one incidence of violence in last12 months.5 The study also identified that verbalabuse was the most prevalent type of violenceagainst healthcare providers. Relatively higherincidents have been reported from departmentsinvolved in provision of acute care particularlyEmergency and Obstetrics and GynaecologyVol. 34 No. 6www.pjms.com.pk1336

Lubna Baig et al.departments.5,6 Another multicenter cross-sectionalsurvey of trainee physicians working in emergencydepartments of nine major tertiary care hospitalsin Pakistan found that 76.9% of the physicianshad experienced some kind of violence.7 Thecommonest reasons cited for increased violenceon healthcare by patients’ attendants in Pakistaninclude; unreasonable expectations of patientsand their families, poor quality of healthcareservices and lack of trust on healthcare providers.Moreover, lack of education among general publicand poor security measures in hospital and failureto communicate important information effectivelyto patients and their attendants has also been citedas reasons that incite violence on health ation of health related information topatients and their families can reduce violenceagainst healthcare.7-9 However, most of the peopleare reluctant to communicate any potentiallydisturbing or stressful information; consideringit to be “Bad News”.10,11 Breaking bad news maylead to disappointment, distress and aggression inthe receiver(s) and has a high potential to provokeviolence depending on contextual factors.10,11A qualitative study of experiences of healthcareproviders regarding breaking bad news analyzedbad and good experiences separately and identifiedthat interpersonal communication skills andspecific training of healthcare providers regardingbreaking bad news predominantly influencedoutcomes of breaking bad news.12 The previousmodels of breaking bad news ignore the specificsocial context and have limited usability incountries like Pakistan.11,13 Hence, it is not onlyimportant to understand the reasons and context ofviolence against healthcare in response to breakingbad news but also the positive experiences ofhealth care providers (HCPs) that helped mitigatethose situations. This study was conducted todevelop a contextual model for effective and safercommunication of bad news in settings with highpotential for violence against healthcare.METHODSA qualitative exploratory study was conductedin August, 2016 in tertiary healthcare settings ofKarachi to identify the reasons for violence related tobreaking bad news and suggestions of participantsin its management. Six Focus Group Discussions(FGDs N 45) and 14 in depth interviews (IDIs,N 14) were conducted with purposive sampling ofHCPs working in the departments of Emergency,Pak J Med SciNovember - December 2018Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medicine of sixpublic and private sector hospitals which includedJinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, CivilHospital, Ziauddin Hospital, Sindh GovernmentHospital-Korangi, Sindh Government HospitalLyari and Sindh Government Hospital-Malir. Therespondents included; doctors, nurses, residents,dispensers and paramedics from seven public andprivate tertiary care hospitals. Using theoreticalsampling the data collection was stopped whensaturation was reached.Semi structured interview guides were used afterpre-testing. All the FGDs and IDIs were videorecorded and audio-taped. Data was transcribedand translated into “English” by a languageexpert. The transcripts of IDIs were discussedwith the respondents to ensure the reliability andauthenticity of the data.Data was analyzed using thematic contentanalysis. Both ‘manifest content’ (visible, obviouscomponents) and ‘latent content’ (underlyingmeaning) of the text were analyzed. The principalinvestigator (PI) and two co-investigators analyzedthe data independently to identify codes andthemes, which were finalized with consensus.Ethical approval for the proposed study wasobtained from Institutional Review Board (IRB)of Jinnah Sindh Medical University and relevanthealth care settings. Informed consent was takenfrom all study participants before the IDI or FGD.RESULTSThe study identified a number of reasons forviolence against healthcare in response to breakingbad news. The causes of violence were classified asclient and provider related causes. The client relatedcauses included impatience or lack of tolerance, lackof respect towards healthcare providers, unrealisticexpectations from healthcare facility or healthcarestaff. A HCP from emergency department of apublic sector hospital mentioned;“Violence occurs when people become emotional inresponse to adverse health outcomes “, (EmergencyMedical Officer)The provider-related causes included: badattitude of HCPs towards patients and attendants,lack of timely communication, inability to counselpatients/attendants and appropriate preparation forundesirable outcomes. One study participant said;“Incompetency to counsel patients and theirfamilies and bad attitude of doctors with staff andattendants causes violence in healthcare settings”.(Nurse Supervisor)Vol. 34 No. 6www.pjms.com.pk1337

Breaking Bad NewsThe study participants suggested variousstrategies to help reduce violence in healthcaresettings related to receiving bad news. Training incommunication especially breaking bad news wassuggested by most participants a postgraduatetrainee said;“Training of health care providers in communicationskills may help in reducing violence”.Most of the healthcare providers emphasizedthat violence in healthcare settings can be reducedby implementing specific patient-communicationprotocols. Based on the themes and subthemesemerging from data analysis a context specifictraining module was developed to train HCPs foreffective and safer communication of sensitiveinformation or breaking bad news. This modeloffers a contextualized stepwise approach tobe used by healthcare providers for effectivecommunication of bad news while ensuringhealthcare providers safety as well. Currently, thismodel is being implemented in some tertiary careteaching hospitals of Karachi and the effectivenessof the entire training on de-escalation of violencewas found to be effective which also included themodel on breaking bad news.14DISCUSSIONThis is the first study which specifically exploredways to effectively manage breaking bad newsin the local context. Our study identified lack ofcommunication skills and empathic attitude amonghealthcare providers that resulted in violenceagainst healthcare. This is in concurrence with thestudy done in Pakistan with residents related tobreaking bad news.15 Previous studies have shownthat empathic attitude of healthcare providersBox 1: Details of breaking bad news model proposed to reduce violence in healthcare settings of Pakistan.Pak J Med SciNovember - December 2018Vol. 34 No. 6www.pjms.com.pk1338

Lubna Baig et al.increases the effectiveness of management and alsoimproves patient s compliance to treatment andenhances their self-efficacy.16,17Our proposed model also emphasizes that trainingon communication skills is also important whileimplementing the step-wise approach for breakingbad news to patients and or their attendants. Ourmodel has some similar characteristics/ constructswith a previous model Known as “SPIKE Strategy”for breaking bad news by Buckman. The SPIKEstrategy focuses on demonstration of empathicattitude while recognizing and addressing emotionsat receivers end and is not specifically designed forcommunication of bad news.18SPIKE does not offer essential guidance aboutidentifying the right person for breaking the badnews in case many attendants are present. Thisin our opinion is very important in the contextof Pakistan where families visit their patients ingroups due to cultural practices and limited healthliteracy. Moreover, unstable political environmentand extremism increases possibility to encounterpolitical or religious mobs at hospitals and requiresa specific strategy to deal with a larger group ofemotionally heightened people.A number of studies have identified the crucialrole of cultural values and context for patientcentered communication in improving patientsatisfaction and psychological well‑being.19‑23Hence, our model also incorporates and appliescultural values by engaging attendants in prayersfor recovery and life of a patient who arrived deadin case when they seem to be in denial or reluctant tohear any unwanted news.19 This can help to preparethem psychologically to hear bad news whilediffusing anger and reduce chances of violence dueto acute rage. This also provides sufficient time tothe healthcare team to ensure necessary securityarrangements as required by the situation.Similarly, our model advocates using simplelanguage and avoiding use of medical jargonwhile breaking the bad news to ease the uptakeof information at receivers end which is alsosupported by SPIKES.18 However, this approach iscontrary to another model known as “P-A-T-I-E-NT-E” Protocol developed specifically in the contextof Brazil.24 This difference in the use of medicaljargons or key terms for medical conditions may beexplained on the basis of difference in the literacyrates of two countries. Hence, in Pakistan, wherethe literacy rate is very low the use of medicaljargon or key terms while breaking bad news maycause confusion and may lead to violence.Pak J Med SciNovember - December 2018Consequently, this study proposes first everhealth communication model for Pakistan andprovides evidence based guidelines to break badnews effectively in the context of Pakistan andsimilar cultures. Inclusion of study participants fromhealthcare settings frequently involved in breakingbad news from multiple hospitals of metropolitancity of Karachi increases trustworthiness of studyfindings. Analysis of data by more than tworesearchers establishes the credibility of the finding.Although the effectiveness of the model has notbeen tested independently but the effectiveness ofde-escalation of violence training was found to bepositive which also included training on breakingbad news model.14Disclaimer: The adaptation of this contextual modelis dependent on basic communication skills of thehealthcare providers; hence, this calls for basictrainings in communication along with adaptationof this contextual model. This model mainlyaddresses challenges of breaking bad news inemergency conditions in one episode and does notprovide specific guidelines about role of frequentconsultations to break the bad news if patient orattendants are not well prepared to receive thecomplete news or information as suggested byDean and Willis.19CONCLUSIONIncorporating socio-cultural context in patientcommunication can improve their satisfaction andcompliance to the information provided. The fivestep Model of Breaking bad news is a contextualmodel and can be tried in Pakistan and similarcountries with local adaptation.Acknowledgement: To the staff and team ofHCID for collecting data and specially Ms. LubnaMazharullah for transcribing the data.Grant Support & Financial Disclosures: Thisresearch and the training manual were funded byInternational Committee of Red Cross (ICRC).REFERENCES1.2.3.Fair CC, Malhotra N, Shapiro JN. Faith or doctrine? Religionand support for political violence in Pakistan. PublicOpinion Quarterly. 2012;76(4):688-720.Syed SH, Saeed L, Martin RP. Causes and incentives forterrorism in Pakistan. J App Secur Res. 2015;10(2):181-206.Doctors killed in Pakistan: 2001-2015. (Cited on 28th April2015). Available from URL: /casualties./Doctors killedPakistan.htm.Vol. 34 No. 6www.pjms.com.pk1339

Breaking Bad am MY, Farooqi MS, Mazharuddin SM,Hussain A. Workplace violence experienced by doctorsworking in government hospitals of Karachi. J CollPhysicians Surg Pak. 2014;24(9):698-699.Baig LA, Shaikh S, Polkowski M, Ali SK, Jamali S,Mazharullah L, et al. Violence Against Health CareProviders: A Mixed-Methods Study from Karachi, Pakistan.J Emerg Med. 2018;54(4):558-566.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.12.047Zafar W, Siddiqui E, Ejaz K, Shehzad MU, Khan UR, JamaliS, et al. Health care personnel and workplace violence inthe emergency departments of a volatile metropolis: resultsfrom Karachi, Pakistan. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):761-772.doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.049.Mirza NM, Amjad AI, Bhatti AB, Shaikh KS, Kiani J, YusufMM, et al . Violence and abuse faced by junior physiciansin the emergency department from patients and theircaretakers: a nationwide study from Pakistan. J Emerg Med.2012;42(6):727-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.01.029.Duxbury J, Whittington R. Causes and managementof patient aggression and violence: staff and patientperspectives. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(5):469-478. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03426.x.Hahn S, Hantikainen V, Needham I, Kok G, Dassen T,Halfens RJ. Patient and visitor violence in the generalhospital, occurrence, staff interventions and consequences:a cross-sectional survey. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(12):2685-2699.doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05967.x.Dibble JL, Sharkey WF. Before breaking bad news:Relationships among topic, reasons for sharing, messengerconcerns, and the reluctance to share the news. Commun Q.2017;65(4):436-455. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2017.1286363.Buckman R. How to Break Bad News: A guide for healthcareprofessionals. N Engl J Med. 1992;329:223.Dickson D, Hargie O, Brunger K, Stapleton K. Healthprofessionals’ perceptions of breaking bad news. Int JHealth Care Qual Assur. 2002;15(7):324-336.Saaiq M, Zaman KU. Breaking bad news in emergency:How do we approach it? Ann Pak Inst Med Sci. 2006;2:72-74.Baig L, Tanzil S, Shaikh S, Hashmi I, Khan MA, PolkowskiM. Effectiveness of training on de-escalation of violence andmanagement of aggressive behavior faced by health careproviders in a public sector hospital of Karachi. Pak J MedSci. 2018;34(2):294-299. doi: 10.12669/pjms.342.14432.Jameel A, Noor SM, Ayub S. Survey on perceptions andskills amongst postgraduate residents regarding breakingbad news at teaching hospitals in Peshawar, Pakistan. J PakMed Assoc. 2012;62(6):585.Blasi ZD, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleinjnen J.Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematicreview. Lancet. 2001;357:757-762.Pak J Med SciNovember - December 201817. Halpern J. From Detached Concern to Empathy: HumanizingMedical Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;200. Available from URL: 33/pdf/1373.pdf.18. Buckman RA. Breaking bad news: the SPIKES strategy.Community Oncol. 2005;2(2):138-142.19. Dean A, Willis S. The use of protocol in breaking bad news:evidence and ethos. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016;22(6):265-271.doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2016.22.6.265.20. Rollins LK, Hauck FR. Delivering bad news in the context ofculture: a patient-centered approach. JCOM. 2015;22(1):2126.21. Vail L, Sandhu H, Fisher J, et al. Hospital consultantsbreaking bad news with simulated patients: an analysis ofcommunication using the roter interaction analysis system.Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:14:185-194. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.016.22. Hack TF, Pickles T, Ruether JD, et al. Behind closeddoors: systematic analysis of breast cancer consultationcommunication and predictors of satisfaction withcommunication. Psychooncology. 2010;19(15):626-636. doi:10.1002/pon.1592.23. Cantwell BM, Ramirez A. Doctor-patient communication: astudy of junior house officers. Med Educ. 1997;31:17-21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb00037.x/pdf.24. Pereira CR, Calônego MA, Lemonica L, Barros GA. TheP-A-C-I-E-N-T-E Protocol: An instrument for breaking badnews adapted to the Brazilian medical reality. Rev AssocMed Bras. 2017;63(1):43-49. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.01.43.Author s Contribution:LB: Conceived the idea, designed the study,analyzed data and conceptualized the proposedbreaking bad news model and did final edits on themanuscript.ST: Participated in coding and analysis and wrotethe first draft of manuscript.SKA did the data analysis wrote the concept in themanual and edited the first and second draft.SS: Participated in coding and statistical analysisand wrote methodology section of the manuscript.MK: Participated in coding and statistical analysisand wrote methodology section of the manuscript.SJ for helping in data collection at JPMC andrefining the model of breaking bad news.Vol. 34 No. 6www.pjms.com.pk1340

Lubna Baig1, Sana Tanzil2, Syeda Kauser Ali3, Shiraz Shaikh4, Seemin Jamali5, Mirwais Khan6 ABSTRACT Objectives: The purpose of the study was to identify the sequence of violence that ensues after breaking bad news and develop a contextual model of breaking bad news and develop a model contextual for Pakistan.

way of breaking bad news for patient and professional alike. To this end, a number of strategies have been developed to support best practice in breaking bad news such as the SPIKES protocol (Baile et al, 2000) and Kayes 10 steps (1996). Royal College of Nursing (RCN, 2013) guidance for nurses breaking bad news to parents

· Bad Boys For Life ( P Diddy ) · Bad Love ( Clapton, Eric ) · Bad Luck (solo) ( Social Distortion ) · Bad Medicine ( Bon Jovi ) · Bad Moon Rising ( Creedence Clearwater Revival ) · Bad Moon Rising (bass) ( Creedence Clearwater Revival ) · Bad Mouth (Bass) ( Fugazi ) · Bad To Be Good (bass) ( Poison ) · Bad To The Bone ( Thorogood .

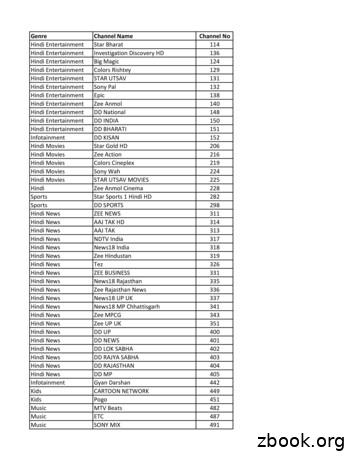

Hindi News NDTV India 317 Hindi News TV9 Bharatvarsh 320 Hindi News News Nation 321 Hindi News INDIA NEWS NEW 322 Hindi News R Bharat 323. Hindi News News World India 324 Hindi News News 24 325 Hindi News Surya Samachar 328 Hindi News Sahara Samay 330 Hindi News Sahara Samay Rajasthan 332 . Nor

81 news nation news hindi 82 news 24 news hindi 83 ndtv india news hindi 84 khabar fast news hindi 85 khabrein abhi tak news hindi . 101 news x news english 102 cnn news english 103 bbc world news news english . 257 north east live news assamese 258 prag

bad jackson, michael bad u2 bad angel bentley, d. & lambert, m. & johnson, j. bad at love halsey bad blood sedaka, neil bad blood swift, taylor bad boy for life (explicit) p. diddy & black rob & curry bad boys estefan, gloria

CONGRATULATING FRIENDS FOR DIFFERENT OCCASIONS Good news, bad news These lessons cover language you can use when you want to give or react to news. Includeing: Congratulating someone on good news Responding to someones bad news Giving good news Giving bad news Responding to someone's good news

RESEARCH BY JESSE LIVERMORE*: SEPTEMBER 2020 . An upside-down market is a market in which good news functions as bad news and bad news functions as good news. The force that turns markets upside -down is policy . News, good or bad, triggers a countervailing policy response with effects th

The level of management responsible for developing strategic goals is: A. line B. supervisor C. functional D. senior . D. other organisations that do business with the 14 Where a stakeholder is identified as having high interest and low power, an organisation should: keep them satisfied monitor their interests and power C. manage them closely keep them informed 15. Highfield Aeet 12 .