2. Professional Ethics - Elsevier

A43346-Ch02.qxd19/01/064:55 PMPage 132. Professional EthicsTruth, trust and communicationsskillsWhen God said that lying was a sin, he made anexception for doctors, and he gave them permission tolie as many times a day as they saw patients.DumasWhen Dumas wrote the above, it was probablymeant to be slightly ironic. However, it does reflectthe historical notion that the extent to whichpatients are told the truth was a matter for thedoctor to decide. The Hippocratic Oath is notablysilent on the issue of telling patients the truth. Infact, Hippocrates advised the physician to ‘calmlyand adroitly conceal most things from their patients. . . turning his attention away from what is beingdone to him . . . revealing nothing of the patient’sfuture or present condition’. So from ancient timesuntil comparatively recently, lying to patients wasnot necessarily disapproved of, or even discouraged.Indeed ‘to lie like a physician’ used to be acompliment!Current thought is completely different. TheGeneral Medical Council (GMC) states that doctorshave a duty to be ‘honest and trustworthy’. TheBristol Royal Inquiry made 37 recommendations onhow a greater culture of respect and honesty could befostered within the NHS. Withholding the truth includes: Outright lies. Temporary deception. Not answering directquestions.Giving false hope.Telling the truthThe concept of ‘telling the truth’ has two facets:1. The ‘telling’ part, which deals with thecommunication of information.and2. The ‘truth’ part, which holds that theinformation given has to be true.From an ethical perspective, truthful informationis important for a number of reasons: For reasons of autonomy; truthful informationhelps patients to decide how to proceed withtreatment. Even if the information doesn’t lead to atreatment decision, the patient may still wish toknow information about their health, becausetheir health is intricately linked with their sense ofself. For reasons of trust, it is generally accepted thattruth-telling promotes a sense of trust betweenboth the doctor and their patient, and in generalbetween doctors and the public at large.So, it seems that in general, truth-telling is anecessary duty. However, is it an absolute one? Arethere any circumstances in which it might be okay tolie to patients? What about not telling the whole truth?Is there a difference between avoiding answering adirect question, and telling a lie? The followingscenarios illustrate the general principles at stake.Scenario 1A patient, Mrs X, is brought to A&E after beingcaught in a house fire. Mrs X’s three children werealso in the fire; two have died and it is not knownwhether the other will survive or not. Mrs X herselfis in a critical condition. Mrs X asks you, the doctortreating her, how her children are.You suspect that telling the truth will distress herso much that it may well lead to her death. Do youdeceive her for a short period of time?Here we have a conflict of ethical principles:1. Respect for autonomy holds we should not lieto our patient.2. Beneficence holds that lying may be crucial insaving the patient’s life.The conflict in principles is mirrored by aconflict in different ethical theories as well:utilitarianism would tell us to lie, Kantianism wouldoblige us to tell the truth. How can a compromisebe reached?13

A43346-Ch02.qxd19/01/064:55 PMPage 14Professional EthicsMrs X has asked a direct question and an illthought-out answer could be fatal to her. Ideally, wewould like to be able to reassure Mrs X without lyingto her. Deflecting her questions may be difficult. Thebad news needs to be communicated to her, but isperhaps best done when her own medical conditionis more stable.It has been suggested that lying to patients isjustified only ‘if a person, acting rationally, werepresented with the alternatives, he or she wouldalways choose being lied to’ (Gert & Culver 1979).The suggestion here is that when trying to promoteautonomy, what is necessary is more than a simplepresentation of potential options, because the way inwhich the options are presented may affect theability of Mrs X to make an autonomous choice.Scenario 2Mr Y has a poor (but not terminal) prognosis due tocancer. You are treating Mr Y, and are about to tellhim his diagnosis and prognosis.Before you do so, his son, a local GP, who hasguessed the diagnosis, urges you not to tell his fatherthe truth. The son explains that his mother, Mr Y’swife, died a mere two months ago of a very aggressivecancer, and he fears that if his father knows the truth,he will ‘give in’ because the father thinks that anydiagnosis of cancer is one without hope of recovery.In this scenario, the deception is not a short-termone to allow recovery, but a permanent one.However, the conflict of principles is similar:autonomy vs. beneficence.Weighing up the two sides of the equation isdifficult because there are two ideas, or conceptions,about the nature of autonomy: One view is that autonomy is about makingdecisions: being in charge of one’s own destiny. A different view is that autonomy is about makingcertain types of decision: specifically the types ofdecision that are consistent with a general lifeplan or goal.These differing conceptions of autonomy aredeveloped further in the section on paternalism.Telling the truth and the lawThe legal implications of truth-telling mainly concernwhether or not the consent given is valid. In order forconsent to be valid, it must be informed consent. Thelaw tends to consider whether doctors have fullydisclosed risks inherent in treatment before obtainingconsent.14 There are different conceptionsof autonomy: Long-term autonomy: valuelies in promoting life-longgoals that are consistent withdeeply held and considered beliefsand values.Short-term autonomy: value lies inbeing able to make decisions aboutone’s own health care – whetherrationally based or capricious.Your views on which conception ofautonomy you consider to be moreimportant may shape whether or notyou believe that deceiving patientscan ever be morally acceptable.The important cases that dealt with disclosure ofrisk are:1. Chatterton v. Gerson [1981] 1 All ER 2572. Sidaway v. Board of Governors of the BethlemRoyal Hospital and the Maudsley Hospital[1985] 1 All ER 643In Chatterton v. Gerson, the courts looked atwhen doctors who didn’t disclose risks would beguilty of trespass to the person. They said that:. . . once the patient is informed in broad terms of thenature of the procedure which is intended, and givesher consent, that consent is real, and the cause of theaction on which to base a claim for failure to go intorisks and implications is negligence, not trespass.The key phrase from this judgement is thatpatients need to be informed ‘in broad terms of thenature of the procedure’. If this is done, then thecharge of trespass, or battery, cannot be brought.The courts also looked at when a non-disclosure ofrisks could lead to a charge of negligence. They saidthat a doctor:. . . ought to warn what may happen by misfortunehowever well the operation is done, if there is a realrisk of a misfortune inherent in the operation.The key phrase here is that doctors ‘ought towarn . . . if there is a real risk’.Who decides what constitutes a real risk waslooked at in the Sidaway case. The outcome of thiscase was an endorsement of the Bolam Test (asdiscussed in Consent section). This test holds that in

A43346-Ch02.qxd19/01/064:55 PMPage 15Informed consent and its elementsquestions of disclosure of risks, a doctor is onlynegligent if there is no reasonable body of medicalpractice that would have made the same choice.Effectively, this means that the medical professionitself sets the standards for disclosure of risk.A popular rule of thumb is to disclose risks thatare greater than 1%. BUT, if there is a grave risk (suchas death or permanent disability), especially forminor procedure, then this 1% rule doesn’t hold, andrisks with a probability of less than 1% must also bedisclosed. However, the doctor is duty-bound toanswer any question truthfully. This is even moreimportant if the procedure is a non-therapeutic one,or safer alternatives exist.Other countries have developed different tests: Australia has a prudent-patient test: here a doctormust disclose those risks that a prudent patientwould wish to know. Japan supports a therapeutic privilege wheredoctors don’t need to disclose risks (or even adiagnosis) if they believe it isn’t in the patient’sbest interests.To avoid a charge of trespassto the person, the doctormust inform the patient ofthe ‘broad terms of thenature of the procedure’.To avoid a charge of negligence, thedoctor must inform the patient ‘ifthere is a real risk’ of harm.What constitutes a ‘real risk’ is setby a degree of consensus within themedical profession. Informed consent and its elementsTreatment without consent can lead to the healthcare practitioner being liable for trespass to theperson, negligence or, in extreme cases, a criminalprosecution of assault or battery.These legal provisions mean that patients can vetocare. Treatment can only be forced upon patients innarrowly defined circumstances. Consent is notrequired when: The patient is unconscious and requires emergencytreatment. Testing for certain infectious diseases: theseinclude the ‘notifiable’ diseases of cholera, plague,relapsing fever, smallpox and typhus.The patient is incapable of giving consent, forexample in cases of mental disability (see p. 52) ora young child (see p. 49). The components of a validconsent Being informed. Capacity.Voluntariness.Making a decision.Informed consent (also see ‘Telling thetruth and the law’)The charge of battery can be brought against a doctorin the following situations:1. Where no consent has been obtained.2. When force is used.3. When the treatment carried out is entirelydifferent from the one specified.Most charges are of negligence: for failure to warnthe patient of risks. The courts determine whichrisks need to be mentioned to patients by using theBolam Test. This test derives from the case of Bolamv. Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957]1 WLR 582.John Bolam was a psychiatric patient undergoingelectro-convulsive therapy (ECT). He was notwarned of a risk of fractures due to the convulsions,nor was he given muscle relaxants, or manuallyrestrained. As a result of the ECT, he sustainedbilateral fractures of the acetabula.The judge defined the test of negligence to be:‘the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercisingand professing to have that special skill’. Becauseother doctors testified that they would have treatedBolam in the same way that he was treated, that is, a‘reasonable body’ of medical practitioners would nothave done anything differently, Bolam’s doctor wasfound not guilty of negligence.The Bolam Test originally applied to all aspects oftreatment and diagnosis. It was applied to warning ofrisks by a subsequent case, that of Sidaway v. Boardof Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital and theMaudsley Hospital [1985] 1 All ER 643.15

A43346-Ch02.qxd19/01/064:55 PMPage 16Professional EthicsThe standard of negligencewas set out by the case ofBolam v. Friern HospitalManagement Committee[1957] 1 WLR 582. It requires thestandard of care not to fall below: ‘thestandard of the ordinary skilled manexercising and professing to have thatspecial skill’. Effectively, this standardis set by the medical profession.Guidelines for obtaining informed consentThe GMC has detailed 12 key pieces of informationto give to patients in order to obtain informedconsent:1. Details of the diagnosis, and prognosis, and thelikely prognosis if the condition is leftuntreated.2. Uncertainties about the diagnosis includingoptions for further investigation prior totreatment.3. Options for treatment or management of thecondition, including the option not to treat.4. The purpose of a proposed investigation ortreatment; details of the procedures or therapiesinvolved, including subsidiary treatment such asmethods of pain relief; how the patient shouldprepare for the procedure; and details of whatthe patient might experience during or after theprocedure including common and serious sideeffects.5. For each option, explanations of the likelybenefits and the probabilities of success; anddiscussion of any serious or frequentlyoccurring risks, and of any lifestyle changes thatmay be caused by, or necessitated by, thetreatment.6. Advice about whether a proposed treatment isexperimental.7. How and when the patient’s condition and anyside effects will be monitored or reassessed.8. The name of the doctor who will have overallresponsibility for the treatment and, whereappropriate, names of the senior members of hisor her team.9. Whether doctors in training will be involved, andthe extent to which students may be involved inan investigation or treatment.1610. A reminder that patients can change their mindabout a decision at any time.11. A reminder that patients have a right to seek asecond opinion.12. Where applicable, details of costs or chargeswhich the patient may have to meet.Remember: when presenting information to thepatient, it must be at an appropriate level. Validconsent can only be given if the patient canunderstand the information. The following may helpwhen presenting information:1. Provide information in the patient’s ownlanguage: this may involve the use of aprofessional interpreter or a member of thepatient’s family. Remember, however, the patientwill have to consent to the use of this person.(This applies to spoken languages and signlanguage.)2. Use leaflets: these can be given to the patient togo away and read. They should be given anopportunity to ask any questions the leaflets mayhave raised. Ensure the leaflets are current.3. Use diagrams: the patient may not know whereher pancreas is; drawing even a simple diagramof where it is in relation to the rest of herorgans, and of the position of a surgical scar, canbe helpful.4. Ask the patient if they would like a familymember or friend to be present.5. Ask if the patient would like to tape-record theconsultation.6. If the consultation involves breaking bad news,do it in a sensitive way. It may also be helpful toinform the patient of counselling services and/orpatient support groups if appropriate.7. Encourage input from other members of thehealth-care team. Patients may more readilyunderstand information from nurses, simplybecause they may feel less nervous or lessembarrassed around them.8. Answer patients’ questions directly, don’t beevasive.9. Allow plenty of time to understand theinformation given.Capacity to consent (competence)Capacity refers to the ability of an individual to makedecisions with respect to their medical treatment. Itis presumed, in the absence of evidence to thecontrary, that adult patients are capable of givingconsent.

A43346-Ch02.qxd19/01/064:55 PMPage 17Informed consent and its elementsThe definition of capacity has been given by theHigh Court in the case Re C (Adult: Refusal ofTreatment) [1994] 1 All ER 819.C was an inpatient at Broadmoor Prison Hospital,diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. C believedhe was an internationally renowned doctor. Cdeveloped gangrene on the toes of one foot. C’ssurgeon believed C should have a below-kneeamputation, but C refused, believing it better to diewith both feet than live with one. C’s solicitorapplied for an injunction to prevent amputation,which was granted, as the courts found that, notwithstanding his schizophrenia, C was capable.The test used in this case to determine thecapacity of C has become known as the Re C Test.The Re C Test has three stages:1. Can the patient take in and retain information?2. Does the patient believe this information?3. Can the patient weigh that information balancingrisks and needs?Remember: in adults, competence is a test for aminimal level of ability to use information given toweigh risks and benefits; it is not specific to thedecision being made. In children, however, apatient’s capacity may vary with the gravity of thedecision involved. Different levels of competence arerequired for different procedures. A child may havethe requisite capacity to agree to a broken wrist beingplastered, but not to consent to treatment forleukaemia.Where there is fluctuating capacity in an adult,capacity when the patient is at their most lucidshould be determined. (This is different in children –see Chapter 3.)Voluntary consentFor consent to be valid, it ought to be free fromcoercion. Whilst patients may take into account theadvice of others – including medical staff, friends,family, police, prison authorities, employers andinsurance companies – they must still feel that theyare able to make an autonomous decision. Consentgiven under duress is invalid.The courts have broadly backed this approach.They have found that consent may be invalidated ifobtained fraudulently, by force or by undue influence(see Re T [1992] 3 WLR 782 below). Furthermore, ifan adult patient refuses to give consent, the courtshave held that no-one else is in a position to giveproxy consent (see F v. West Berkshire HealthAuthority [1989] 2 All ER 545 below).T [1992] 3 WLR 782, 4 All ER 649T was pregnant and involved in a car accident. Shewent into premature labour and needed a caesareansection. Prior to the operation, T had a conversationwith her mother. T’s mother was a Jehovah’sWitness, although T was not.Subsequent to her conversation with her mother,T told hospital staff she did not want a bloodtransfusion. She had not indicated any concern abouta transfusion earlier on.The caesarean section was carried out without theneed for a blood transfusion, although the baby wasstillborn.After the operation, T’s condition deterioratedand she was admitted to ICU. It was decided thatwithout a blood transfusion she would die.The court of appeal decided: The refusal for a blood transfusion during acaesarean section might not apply to the newsituation – by which point T was incapable ofgiving consent. That T had been unduly influenced by hermother’s religious views, and this prevented herrefusal being valid.In this case, Lord Justice Staughton expressed atest for undue influence, saying:In order for an apparent consent or refusal of consentto be less than a true consent or refusal, there must besuch a degree of external influence as to persuade thepatient to depart from her own wishes, to an extentthat the law regards it as undue.F v. West Berkshire Health Authority [1989] 2All ER 545F was a 36-year-old woman, with a mental age of 5.F was a long-term resident of a mental hospital, andhad formed a sexual relationship with a maleresident.F’s mother and doctors thought that F ought to besterilized.The courts stated that: For a patient of adult age, no-one could give proxyconsent. In the case of an incompetent patient, doctorscould only act in the best interests of theirpatient. The ‘best interests’ would be decided on whetherthe doctor acted in accordance with a responsibleand competent body of relevant professionals – thatis, in accordance with the Bolam Test (see sectionon informed consent).17

A43346-Ch02.qxd19/01/064:55 PMPage 18Professional EthicsWhat are a patient’s ‘best interests’? (see also‘Mental disorders and competence to consent’)How do doctors, or the courts, decide what anincompetent patient’s best interests are? The courtsthemselves have not given a clear definition of ‘bestinterests’ (Fig. 2.1). However, the Draft MentalIncapacity Bill (2003) included the following pointsthat should be considered: Whether the person is likely to have capacity inrelation to the matter in question in the future. The need to permit and encourage the person toparticipate, or improve their ability to participate,as fully as possible in any act done for and anydecision affecting that person. That person’s past and present wishes, feelingsand those factors that the person would considerif they were able to do so. The views of those caring for the

A patient, Mrs X, is brought to A&E after being caught in a house fire. Mrs X’s three children were also in the fire; two have died and it is not known whether the other will survive or not. Mrs X herself is in a critical condition. Mrs X asks you, the doctor treating her, how her children are. You suspect that telling the truth will distress her

Professional Ethics Professional societies develop polices for their own industries, and the societies hold their members to that code of ethics. Professional ethics is different from studying philosophical ethics. Professional ethics encompass how people work in a professional setting by following expected standards of behavior (Strahlendorf).

Sampling for the Ethics in Social Research study The Ethics in Social Research fieldwork 1.3 Structure of the report 2. TALKING ABOUT ETHICS 14 2.1 The approach taken in the study 2.2 Participants' early thoughts about ethics 2.2.1 Initial definitions of ethics 2.2.2 Ethics as applied to research 2.3 Mapping ethics through experiences of .

Sep 30, 2021 · Elsevier (35% discount w/ free shipping) – See textbook-specific links below. No promo code required. Contact Elsevier for any concerns via the Elsevier Support Center. F. A. Davis (25% discount w/free shipping) – Use the following link: www.fadavis.com and en

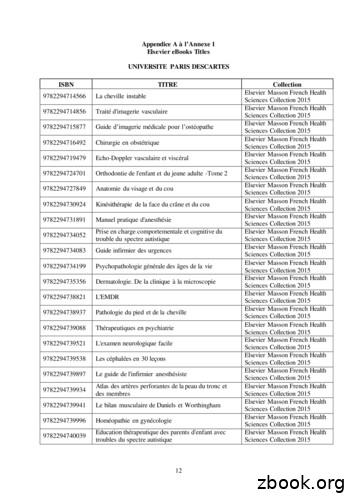

9782294745027 Anatomie de l'appareil locomoteur-Tome 1 Elsevier Masson French Health Sciences Collection 2015 9782294745294 Méga Guide STAGES IFSI Elsevier Masson French Health Sciences Collection 2015 9782294745621 Complications de la chirurgie du rachis Elsevier Masson French Health Sciences Collection 2015 9782294745867 Le burn-out à l'hôpital Elsevier Masson French Health Sciences .

Code of Ethics The Code of Ethics defines the standards and the procedures by which the Ethics Committee operates.! More broadly, the Code of Ethics is designed to give AAPM Members an ethical compass to guide the conduct of their professional affairs.! TG-109! Code of Ethics The Code of Ethics in its current form was approved in

"usiness ethics" versus "ethics": a false dichotomy "usiness decisions versus ethics" Business ethics frequently frames things out, including ethics Framing everything in terms of the "bottom line" Safety, quality, honesty are outside consideration. There is no time for ethics.

Definition of Ethics "A codification of the special obligations that arise out of a person's voluntary choice to become a professional, such as a social worker" "Professional ethics clarify the professional aspects of a professional practice" "Professional social work ethics are intended to

1 Introduction to Medical Law and Ethics Dr. Gary Mumaugh Objectives Explain why knowledge of law and ethics is important to health care providers Recognize the importance of a professional code of ethics Distinguish among law, ethics, bioethics, etiquette, and protocol Define moral values and explain how they relate to law, ethics and etiquette