In Defense Of Graphic Novels I - University Of Alaska .

Kathryn Strong HansenIn Defense ofGraphic NovelsIn the 18th century, critics grumbledabout a new literary form that supposedly threatened the abilities ofyouth to distinguish between reality and artificiality. This kind of text, the criticismran, misinformed its readers about love, morals, social class, and everything that society most valued.This form was the novel, one of the literary formsthat critics now hold dearest. New forms often attract scorn, which is why “novel,” meaning “new,”originally was a term to disparage this Johnnycome-lately style of writing. But newness isn’t ajustification for dismissing something outright.Currently, the graphic novel receives a great deal ofcriticism, much of which betrays a dislike of whatis new rather than a carefully considered critiqueof the graphic novel as a genre. Yet many teachershave shown how graphic novels can help energizestudents whose interests are hard to capture, can aidlow-level and nonnative English-speaking readersthrough the twinning of words with images, andcan challenge higher-level readers to expand theiranalytical skills to include consideration of visualelements.These rewards are worth a battle or two withthose who might criticize these unfamiliar, undervalued texts. Despite this, teachers might find thatthey have more battles than they initially anticipatewhen they set out to include graphic novels in theircurricula. I hope that teachers consider graphicnovels for inclusion into their classrooms, but before they do so, teachers need to consider carefullythe criticism that they are likely to face. By settingforth these potential criticisms, I aim to help pre-The author describes whyshe teaches graphic novelsand directly confrontscriticism teachers may facefrom colleagues,administrators, parents,and students as they firstteach examples of this fastgrowing genre.pare teachers to counter these criticisms successfully so that they have at their disposal a uniquelyuseful body of literature.Perhaps one reason that graphic novels areon the receiving end of so much skepticism is thatthe terms used to categorize the genre aren’t clearlyset. While graphic novel is a common term, otherterms also pop up: sequential art, manga, comics, novelin pictures.1 Equally problematic can be the definition of these terms. In essence, a graphic novel canbe thought of as a sequence of images, often (butnot always) accompanied by text that tells a storyor provides information. This definition is imprecise at best. But I argue that the hazy definitiontelegraphs part of the graphic novel’s appeal. Theboundlessness of the category of graphic novel hintsat its almost limitless possibilities, which is what Iwould suggest teachers tell doubting parents andadministrators. Some graphic novels can be toolsfor introducing different cultures, like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), a tale about a young Iranigirl, and Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese(2006). Other graphic novels are expressly educational, such as Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos H.Papadimitriou’s Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth(2009), which tells about Bertrand Russell’s studiesin mathematics, and Shin Takahashi’s The MangaGuide to Statistics (2008), which explains statisticsconcepts that are useful to marketing. Numerous graphic novels are fictional narratives of manykinds. The wide range of stories told, themes advanced, and information presented provides opportunities for the genre to develop in any numberof ways. This means that the graphic novel has theEnglish Journal 102.2 (2012): 57–6357Copyright 2012 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved.EJ Nov2012 B.indd 5711/7/12 1:24 PM

In Defense of Graphic Novelspotential to appeal to almost any reader. So despitethe definitional and terminological issues, graphicnovels are a vibrant and compelling tool for teaching, and in particular the teaching of writing andof literature.Criticism from Outside the ClassroomBefore discussing how to prepare for some unexpected battles, I will first address the criticismslikely to emerge from disapproving voices outsidethe classroom that teachers might indeed expect.One such expected argument raised against graphicnovels, likely related to their most common name,is that they’re too violent, too brutal, or, in a word,too graphic. This criticism might refer to the superhero comics, in which overlyUneasy teachersmuscled characters show theircan find a valuableworth by physically subduingtheir antagonists. In some reresource in theirspects, this is a valid criticism,local comics shop;especially when the assumedmanagers and workersaudience consists of youngthere can help teacherschildren, even though it is asearch throughradically simplistic overviewgraphic novels to findof superhero graphic novels.As is the case with any genrethose that are bestof text, not all graphic novelssuited to particularare intended for younger auclassroom needs.diences. This is a notion thatteachers must keep in mind. To help emphasize thispoint, think of it this way: many currently popularanimated television shows are analogous to graphicnovels. That is, some people think that the seemingly childish format (animation for televisionshows or “cartoon art” for graphic novels) indicatesthat the material is targeted at children. As showssuch as Family Guy and South Park demonstrate,this is not always the case. But the need for teachers to choose graphic novels wisely shouldn’t bar allgraphic novels from classroom use. Some graphicnovels have names that pretty clearly label them asbeyond the pale for most school use, such as Jhonen Vasquez’s Johnny the Homicidal Maniac (1995–97). Others, including Frank Miller’s Hard Boiled(1990–92); John Wagner, Carlos Ezquerra, and PatMills’s Judge Dredd (1990–present); and John Albano’s Jonah Hex (1971–present), are just as inappro-58priate for young children, though an examinationof them is necessary to ascertain that. If a noviceteacher of graphic novels is worried about text selection, aids exist that provide guidance for usinggraphic novels in the classroom (see fig. 1). Uneasyteachers can also find a valuable resource in theirlocal comics shop; managers and workers there canhelp teachers search through graphic novels to findthose that are best suited to particular classroomneeds.But the existence of objectionable material insome examples of the form does not excuse opposingthe entire canon of graphic novels. Graphic novelsrange widely in content, so careful selection of textsby instructors can obviate these kinds of claims.First and foremost, no teacher should use a graphicnovel that she or he has not read. These texts vary inquality as well as content. This shouldn’t be a surprise, but like most genres, the genre of the graphicnovel encompasses a wide range of topics. Thoughmany critics of the form believe that punches andbullet sprays are the hallmarks of all graphic novels, this is absolutely untrue. For instance, CraigThompson’s Blankets (2003) tells a story of a teenfrom an evangelical Christian background and hisdifficulties in coming of age. Its panels are showcases of the tumultuous nature of first love and ayoung man’s maturation, not fisticuffs—emotionalintensity, not physical violence. For middle school–aged readers, Barry Deutsch’s Hereville: How MirkaGot Her Sword (2010) provides a plucky youngheroine who comes to terms with her longing for aless-traditional life even as she learns better to understand her stepmother. These complex charactersexemplify the wide range of graphic novel characters who exist in a world far apart from one featuring battles between superheroes and supervillians.Even those who don’t find themselves bothered by violence might complain that graphicnovels are easy texts for lazy readers. This is by nomeans the case, but this might be the most persistent criticism to combat. Yet challenging andengaging graphic novels abound. Neil Gaiman’sThe Sandman series (1989–96) frequently makesallusions to classical literature, for example, withthe character of Orpheus from Greek myth making repeated appearances. Gaiman also riffs on theplots of William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’sNovember 2012EJ Nov2012 B.indd 5811/7/12 1:24 PM

Kathryn Strong HansenFIGURE 1. Resources for Beginning to UseGraphic Novels in the ClassroomCarter, James Bucky, Ed. Rationales for TeachingGraphic Novels. Gainesville: Maupin House, 2010. CDROM. This sets forth synopses and potential objectionsfor almost 100 graphic novels, giving educators information to explain these works’ worth to administrators.Comic Shop Locator, http://www.comicshoplocator.com/. This site allows users to find comic shops in theirvicinity and provides additional information, such asgraphic novel reviews and notifications of upcomingconferences.Comics Worth Reading, http://comicsworthreading.com. This site offers Johanna Draper Carlson’s catalogof graphic novels, manga, and other related works. Her“Must-Read Comic Classics” list is a good startingpoint.Cooperative Children’s Book Center, vels.asp. TheUniversity of Wisconsin–Madison’s School of Educationhosts this site, which provides lists of recommendedgraphic novels as well as resources for understandingand defending them.Graphic Novels Program Guide, files/NA63 web.pdf.Bright Point Literacy’s guide includes ideas for usinggraphic novels in the classroom.Great Graphic Novels for Teens, http://www.ala.org/yalsa/ggnt. This site showcases the Young Adult LibraryServices Association’s list of recommended graphic novels for older children.Newsarama, http://www.newsarama.com/. Actor/director Kevin Smith’s site keeps abreast of graphicnovel news, including reviews and information aboutmovie adaptations.No Flying, No Tights, http://noflyingnotights.com/.This website is a storehouse for reviews of graphic novels that do not feature superheroes.Teaching Comics, http://www.teachingcomics.org. Thewebsite of the National Association of Comics Art Educators provides lesson plans, handouts, study guides,and other resources for classroom use of graphicnovels.Using Graphic Novels with Children and Teens: A Guidefor Teachers and Librarians, -and-librarians. Scholastic’swebsite provides a printable PDF that offers graphicnovel suggestions for young readers, middle gradereaders, and young adult readers as well as a list ofadditional resources for educators.Young Adult Library Services Association, wards/greatgraphicnovelsforteens/gn.cfm. This site gives an annuallist of “Great Graphic Novels for Teens.”Dream and Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Talesin installments of The Sandman, creating possiblejumping-off points for introducing—or reexamining—those works. Even without taking intoaccount the beautiful and compelling images inGaiman’s graphic novels, their complex stories andrich character developmentWhile most peoplecreate pleasurable chalclaim to honor art as alenges for readers. Gaiman’swork serves as only one excultivating force, some ofample; another engagingthose same people alsopiece of literature is foundloudly oppose graphicin David B.’s autobiographnovels because they soical graphic novel Epilepticheavily rely on visual(2002). The central characelements.ter’s family slowly unravelsas they try to cure his epileptic brother. A moving account of how familiesexperience suffering and disease, it also shows theyoung protagonist’s escape into imagination as acoping mechanism. As a result, this graphic novelraises issues of the differences between literality andmetaphor. These examples demonstrate only a tinybit of the complexity offered in the plot, characterization, and themes of graphic novels.But it’s also important to take into accountthe subtlety and beauty of graphic novels’ artwork.The argument of lazy readership discounts thepower and impact of images. While most peopleclaim to honor art as a cultivating force, some ofthose same people also loudly oppose graphic novels because they so heavily rely on visual elements.Imagery and drawings are not inherently less valuable than verbal, “literary” art. In fact, images oftenconvey a richness and depth of ideas that requireinterpretation and high-level critical thinking,analysis, and evaluation skills. These are the samekinds of thinking skills and interpretative activitiesthat reading affords students, and I invite teachers to remind skeptics of this. Take as an examplea panel from Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize–winning graphic novel Maus I (1986), an account ofone family’s struggles to survive the Holocaust. Inone sample panel (125), two mouse-headed characters walk on a path through what looks like a park.The simplicity of the drawing style initially mightappear sweet and charming—and it is. But thispanel simultaneously shows the relentlessness andEnglish JournalEJ Nov2012 B.indd 595911/7/12 1:24 PM

In Defense of Graphic Novelsinescapability of Nazism, because even the paththat these characters tread is shaped like a swastika.The darkness and twisted lines of the landscape underscore and enhance this feeling of pervasive doom.When juxtaposed with the sweetness of line drawings of mice, the enormity of the horror imposedby the Holocaust is thrown into starker contrast.This one panel provides an opportunity for studentsto explore an image that provides no words forthem, though the panel is by no means unusual inits depth for a graphic novel panel. To describe thisscene, students have to take the role of producers oflanguage. In this way, graphic novels can serve as abasis for writing and critical thinking assignments.They serve as a way of presenting information in aninteresting and engaging manner to spark students’attention, and such assignments demand that students actively produce the language not only to describe these visuals, but to interpret, critique, andanalyze them. (See also Paula Wolfe and DanielleKleijwegt’s discussion of students as “active perceivers” rather than “passive receivers” of graphicnovels in the May 2012 English Journal.)In fact, graphic novels satisfy many of theInternational Reading Association’s and NationalCouncil of Teachers of English’s joint Standardsfor the English Language Arts. The first standardspecifies that students need to read a “wide range ofprint and nonprint texts” (19), and thanks to theircombining of language and visuals, graphic novelssatisfy both of these categories at once. But graphicnovels can help teach manyIf students equateof the aspects of other stangraphic novels withdards, too. They could be usedthe establishment ofto discuss the multifacetedrange of human experiencebasic skills and with(standard 2 [21]); to highlightstruggling learners,textual features such as senbetter readers and selftence structure, context, andconscious students aregraphics (standard 3 [22]); tolikely to want to distanceteach media techniques andthemselves fromfigurative language (standard6 [26]); to aid in learning tothe genre.synthesize data from print andnonprint sources (standard 7 [27]); to develop familiarity with differing cultures (standard 9); andto foster enjoyment in reading (standard 12 [32]).In short, graphic novels are like any other kind ofliterature in their ability to broaden students’ ex-60perience and deepen their appreciation for story.Thinking of graphic novels as somehow outside ofthe realm of literature denies students a chance tomaster standards in engaging ways.Criticism from Inside the ClassroomSo far, I’ve discussed the kinds of criticisms likeliestto come from those with the least familiarity withgraphic novels, a category that is likely to includeparents and administrators. Yet even those who aremore aware of the range, power, and complexity ofgraphic novels might raise criticism of them. Resistance can even come from unexpected groups,and one of the most important critics of graphicnovels could be the students themselves. Eventhough many students express immediate interest in graphic novels, Sean P. Conners writes that astigma exists around graphic novels that may makesome students less likely to embrace the form.Many well-meaning teachers, librarians, and othereducational professionals have touted graphic novels’ use with students whose classroom performancefalls short of desired outcome, and this way of treating graphic novels has not escaped students’ notice.Conners explains that “arguments that foregroundgraphic novels as tools with which to support struggling readers, promote multiple literacies, motivatereluctant readers, or lead students to transact withmore traditional forms of literature have the unintended effect of relegating them to a secondary rolein the classroom; in doing so, they overlook the aesthetic value in much the same way as educators didin the past” (67). Much of the discussion about thebenefit of graphic novels centers on how these textscan help resistant readers and lower-functioningreaders. Yet if students equate graphic novels withthe establishment of basic skills and with struggling learners, better readers and self-conscious students are likely to want to distance themselves fromthe genre. Though part of the successes that teachers describe with using graphic novels involvesmotivating less-than-enthusiastic students to become more active readers, teachers need to monitor how they speak of graphic novels. The stigmaof graphic novels being the province of strugglingreaders threatens to keep other students away fromthe form—or even to discourage those lower-skilledreaders by making them feel as though they are re-November 2012EJ Nov2012 B.indd 6011/7/12 1:24 PM

Kathryn Strong Hansenceiving less challenging texts because they are notcapable of handling more complex texts. Emphasizing the graphic novels’ wide-ranging subjectmatter, stressing their complexity, and focusing ontheir innovative storylines might go far in battlingthe perceived association of graphic novels withpoorer students.Once this hurdle is cleared, many teachersreport wonderful successes with graphic novels intheir classrooms. Maureen Bakis posted her views inan online op-ed piece, joyfully recounting the skillsthat graphic novels helped foster in her students:Using graphic novels allowed students to thinkcritically and analytically, and because the graphicnovels we read elicited sophisticated and maturediscussion about topics that mattered to them,they were able to further develop personal style,voice, and other aspects of their writing. Becausethey developed a passion about the stories and areal appreciation and understanding of the artistryof the comics they were reading, students weremore engaged toward in-depth discussions.Capitalizing on students’ interests, Bakis was ableto enhance her students’ writing. This kind of success is important not only for improving students’writing but also for inspiring a passion for readingamong her students. Other educators report similarresults. In discussing a book group he offered as anelective class, Jonathan Seyfried wrote that “morethan just an elective or book group, our experiencetogether went right to the heart of books and thejoy of reading” (46). For Seyfried, teaching graphicnovels provided unexpected payoffs, and he recountshow students sought him out after the class hadended for reading recommendations—and not justfor graphic novels. This kind of passion is as important in high-achieving students as it is in thosewhose reading skills aren’t as strongly developed.Students might harbor other socially basedbiases regarding graphic novels. Conners discusseshow students are “aware of stigmas attached tographic novels,” and one such stigma is that peoplewho read graphic novels are “social misfits—or, toborrow their [his students’] term, ‘nerds’” (68).Teachers who i

novels are a vibrant and compelling tool for teach-ing, and in particular the teaching of writing and of literature. Criticism from Outside the Classroom. Before discussing how to prepare for some unex-pected battles, I will first address the criticisms likely to emerge from disapproving voices outside .

The comparative effectiveness of graphic novels, heavily illustrated novels, and traditional novels as reading teaching tools has been sparsely researched. During the 2011-2012 school year, 24 mixed-ability fifth grade students chose to read six novels: two traditional novels, two highly illustrated novels and two graphic novels.

series, The Chronicles of Apathea Ravenchilde, from being banned from the Americus public library. Why use Digital graphic novels in schools? Although print graphic novels are an established literary format in school libraries and classrooms, digital graphic novels are a relatively new medium in school settings. The visual nature of digital graphic novels is the way many 21st-century learners .

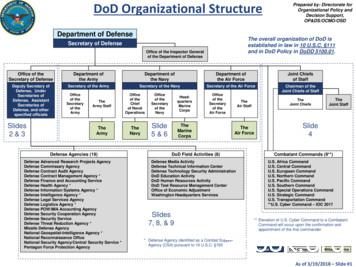

Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Defense Commissary Agency. Defense Contract Audit Agency. Defense Contract Management Agency * Defense Finance and Accounting Service. Defense Health Agency * Defense Information Systems Agency * Defense Intelligence Agency * Defense Legal Services Agency. Defense Logistics Agency * Defense POW/MIA .

literary novels, including but not limited to deep explorations of character, setting, theme, and plot. The key is for readers to look for each element of story in both the words and the artwork in graphic novels. 4. Familiar Genres—Graphic novels can be found in all the genres typically found in tra-ditional literature.

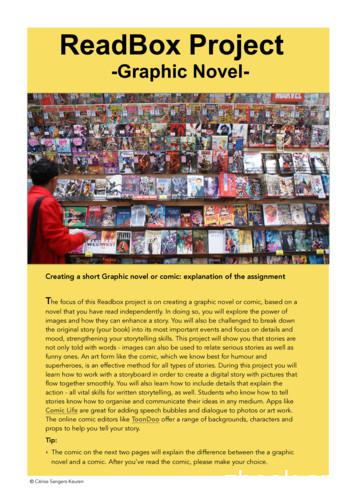

at the graphic novel rubric in order to know you know what your teacher expects from you. Before you begin creating your own graphic novel/ comic, have a look at some samples of graphic novels / comics. Step four: Create a first draft for your own graphic novel/ comic and gather or sketch images. Now that you had a look at other graphic novels and comics, you may already have formed an idea .

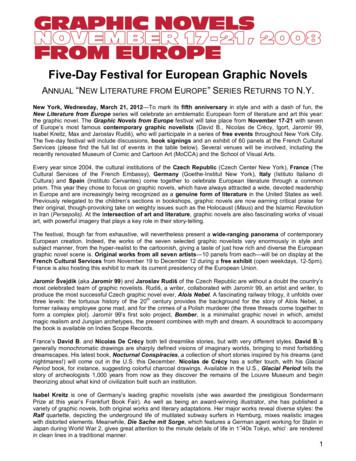

1 Five-Day Festival for European Graphic Novels ANNUAL “N EW LITERATURE FROM EUROPE ” SERIES RETURNS TO N.Y. New York, Wednesday, March 21, 2012 —To mark its fifth anniversary in style and with a dash of fun, the New Literature from Europe series will celebrate an emblematic European form of literature and art this year: the graphic novel. The Graphic Novels from Europe festival will .

not included graphic adaptations of novels. All texts here are original works designed specifically as graphic novels. If you are interested – check out some approved graphic versions of classic texts (Frankenstein, Beowulf

Graphic Organizer 8 Table: Pyramid 8 Graphic Organizer 9 Fishbone Diagram 9 Graphic Organizer 10 Horizontal Time Line 10 Graphic Organizer 11 Vertical Time Line 11 Graphic Organizer 12 Problem-Solution Chart 12 Graphic Organizer 13 Cause-Effect Chart 13 Graphic Organizer 14 Cause-Effect Chart 14