OIG-19-18 - ICE Does Not Fully Use Contracting Tools To Hold Detention .

ICE Does Not Fully UseContracting Tools to HoldDetention FacilityContractors Accountablefor Failing to MeetPerformance StandardsJanuary 29, 2019OIG-19-18

DHS OIG HIGHLIGHTSICE Does Not Fully Use Contracting Tools to Hold DetentionFacility Contractors Accountable for Failing to MeetPerformance Standards January 29, 2019Why WeDid ThisInspectionU.S. Immigration andCustoms Enforcement(ICE) contracts with 106detention facilities todetain removable aliens.In this review we soughtto determine whether ICEcontracting tools holdimmigration detentionfacilities to applicabledetention standards, andwhether ICE imposesconsequences whencontracted immigrationdetention facilities do notmaintain standards.What WeRecommendWe made fiverecommendations toimprove contract oversightand compliance of ICEdetention facilitycontractors.For Further Information:What We FoundAlthough ICE employs a multilayered system to manage andoversee detention contracts, ICE does not adequately holddetention facility contractors accountable for not meetingperformance standards. ICE fails to consistently include its qualityassurance surveillance plan (QASP) in facility contracts. The QASPprovides tools for ensuring facilities meet performance standards.Only 28 out of 106 contracts we reviewed contained the QASP.Because the QASP contains the only documented instructions forpreparing a Contract Discrepancy Report and recommendingfinancial penalties, there is confusion about whether ICE canissue Contract Discrepancy Reports and impose financialconsequences absent a QASP. Between October 1, 2015, and June30, 2018, ICE imposed financial penalties on only two occasions,despite documenting thousands of instances of the facilities’failures to comply with detention standards.Instead of holding facilities accountable through financialpenalties, ICE issued waivers to facilities with deficient conditions,seeking to exempt them from complying with certain standards.However, ICE has no formal policies and procedures to govern thewaiver process, has allowed officials without clear authority togrant waivers, and does not ensure key stakeholders have accessto approved waivers. Further, the organizational placement andoverextension of contracting officer’s representatives impedemonitoring of facility contracts. Finally, ICE does not adequatelyshare information about ICE detention contracts with key officials. ICE ResponseICE officials concurred with all five recommendations andproposed steps to update processes and guidance regardingcontracting tools used to hold detention facility contractorsaccountable for failing to meet performance standards.Contact our Office of Public Affairs at(202) 981-6000, or email us hs.gov OIG-19-18

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland SecurityWashington, DC 20528 / www.oig.dhs.gov-DQXDU\ MEMORANDUM FOR:Ronald D. VitielloDeputy Director and Senior Official Performing theDuties of DirectorU.S. Immigration and Customs EnforcementFROM:John V. KellySenior Official Performing the Duties of theInspector GeneralSUBJECT:ICE Does Not Fully Use Contracting Tools to HoldDetention Facility Contractors Accountable for Failing toMeet Performance StandardsAttached for your information is our final report, ICE Does Not Fully UseContracting Tools to Hold Detention Facility Contractors Accountable for Failing toMeet Performance Standards. We incorporated the formal comments from theICE Office of the Chief Financial Officer in the final report.Consistent with our responsibility under the Inspector General Act, we willprovide copies of our report to congressional committees with oversight andappropriation responsibility over the Department of Homeland Security. We willpost the report on our website for public dissemination.Please call me with any questions, or your staff may contact Jennifer Costello,Deputy Inspector General, or Tatyana Martell, Chief Inspector,at (202) 981-6000.Attachment

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security Table of ContentsBackground . 3Results of Inspection . 7ICE Does Not Consistently Use Contract-Based Quality Assurance Toolsand Impose Consequences for Contract Noncompliance . 7ICE’s Waiver Process May Allow Contract Facilities to CircumventDetention Standards and May Inhibit Proper Contract Oversight . 9Organizational Placement and Overextension of CORs Impede Monitoringof Detention Facilities . 12Lack of Direct Access to Important Contract Files Hinders CORs’ andDSMs’ Ability to Monitor Detention Contracts . 14Conclusion . 15Recommendations . 15AppendixesAppendix A: Objective, Scope, and Methodology . 21Appendix B: Management Comments to the Draft Report . 22Appendix C: Facility Listing and Quality Assurance Surveillance PlanStatus . . 27Appendix D: Office of Inspections and Evaluations MajorContributors to This Report . 31Appendix E: Report Distribution . rage daily populationcontract detention facilityCode of Federal Regulationscontracting officer’s representativededicated inter-governmental service agreementDetention Service ManagerEnforcement and Removal OperationsFederal Acquisition RegulationU.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcementinter-governmental agreementwww.oig.dhs.govOIG-19-18

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security ental service agreementNational Detention StandardsOffice of Detention OversightOffice of Inspector GeneralPerformance-Based National Detention Standardsquality assurance surveillance plan2 OIG-19-18

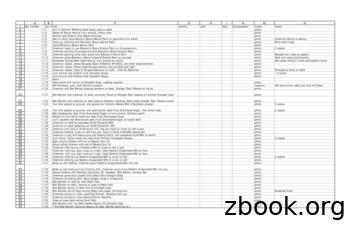

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security BackgroundU.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Office of Enforcement andRemoval Operations (ERO) confines detainees in civil custody for theadministrative purpose of holding, processing, and preparing them for removalfrom the United States. While ICE owns five detention facilities, it has executedcontracts, inter-governmental service agreements (IGSA), or inter-governmentalagreements (IGA) with another 206 facilities for the purpose of housing ICEdetainees.1 Table 1 lists the types and numbers of facilities ICE uses to holddetainees as well as the average daily population (ADP) at the end of fiscal year2017.Table 1: Types of Facilities ICE Uses for DetentionFacility TypeDescriptionService ProcessingCenterFacilities owned by ICE andgenerally operated by contractdetention staff53,263Contract DetentionFacility (CDF)Facilities owned and operatedby private companies andcontracted directly by ICE86,818IntergovernmentalService Agreement(IGSA)Facilities, such as local and countyjails, housing ICE detainees (as wellas other inmates) under an IGSAwith ICE878,778Dedicated IntergovernmentalService Agreement(DIGSA)Facilities dedicated to housingonly ICE detainees under an IGSAwith ICE119,820U.S. MarshalsService IntergovernmentalAgreement (IGA)Facilities contracted by U.S.Marshals Service that ICE alsoagrees to use as a contract rider1006,75621135,435Source: ICE dataNumberofFacilitiesTotal:FY 17 EndADP Unless otherwise indicated, in this report we use the term “contract” in reference to thecontract, IGSA, or IGA instrument used to establish a relationship between ICE and thedetention facility and the term “contract facility” to describe any detention facility operatedunder a contract, IGSA, or IGA.www.oig.dhs.gov3OIG-19-181

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security For this review, we focused on the 106 CDF, IGSA, and DIGSA facilities2 forwhich ICE has primary contracting authority.3 In FY 2017, these 106 facilitiesheld an average daily population of more than 25,000 detainees. Since thebeginning of FY 2016, ICE has paid more than 3 billion to the contractorsoperating these 106 facilities.Key ICE Offices Involved in Contract Management and Facility OversightICE spreads duties for planning, awarding, and administering contracts fordetention management and overseeing contract facilities between Managementand Administration and ERO, resulting in a multilayered system. Figure 1provides the organizational structure for the key offices involved in managingcontracts and overseeing contract facilities.Figure 1: Offices Responsible for Contract Management and OversightICE DeputyDirectorManagement andAdministrationExecutive AssociateDirectorERO ExecutiveAssociate DirectorCustodyManagementOperations SupportField OperationsDetentionManagementDivisionFiscal ManagementDivisionDomesticOperations DivisionDetentionStandardsCompliance UnitBudget ExecutionUnitDomesticOperations EastDetention Planningand AcquisitionsContractManagement UnitDomesticOperations WestICE Health ServicesCorpsAcquisitionsManagementAcquisition ServiceDivisionDetentionCompliance andRemovalOffice of ChiefFinancial OfficerOffice of Budgetand ProgramPerformanceOffice of FinancialManagementDetentionMonitoring UnitSource: Office of Inspector General (OIG) analysis of ICE data See Appendix C: Facility Listing and Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan Status for a listingof the 106 facilities reviewed.3 We did not review contracts from the 100 detention facilities for which the U.S. MarshalsService has primary contracting authority. ICE executed IGAs (contract riders) with the U.S.Marshals Service to house ICE detainees at these facilities.www.oig.dhs.gov4OIG-19-182

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security Within ERO, the Custody Management Division (Custody Management)manages ICE detention operations and oversees the administrative detaineesheld in detention facilities. Custody Management has a Detention StandardsCompliance Unit, which monitors oversight inspections to evaluate compliancewith ICE’s national detention standards. As part of ICE ERO’s development of aDetention Monitoring Program in 2010, Custody Management assignedDetention Service Managers (DSM) to cover 54 contract facilities to monitorcompliance with detention standards. Custody Management also analyzesoperational bed space needs and initiates requests for additional contractfacilities to the Office of Acquisitions Management (Acquisitions Management),within Management and Administration.Acquisitions Management is responsible for preparing, executing, andmaintaining the contracts for detention facilities and for processing anymodifications to contracts. Acquisitions Management contracting officers havesignature authority to execute and modify contracts for detention facilities.Contracting officers also appoint contracting officers’ representatives (COR) tooversee the day-to-day management of each contract facility, but retainultimate authority for enforcing the terms of the contract.ICE has 26 principal COR positions physically located at the 24 ERO FieldOffices to function as liaisons between field operations and contracting. CORsreport to Field Office management and are responsible for ensuring thecontractor complies with the terms of the contract. CORs generally conductdetention facility site visits and should have first-hand knowledge of detentionfacility operations in order to approve invoices for payment and to addressinstances of noncompliance, such as by pursuing contractual remedies. TheField Operations Division provides guidance to and coordination among the 24national ERO Field Offices. The Field Office Directors are chiefly responsible forthe detention facilities in their assigned geographic area.Detention Contracts and Standards ComplianceEach detention facility with an ICE contract must comply with one of three setsof national detention standards: National Detention Standards, 2008Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS), or 2011 PBNDS.These standards (1) describe a facility’s immigration detention responsibilities,(2) explain what detainee services a facility must provide, and (3) identify whata facility must do to ensure a safe and secure detention environment for staffand detainees.www.oig.dhs.gov5OIG-19-18

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security ICE monitors facility compliance with the applicable detention standardsthrough triennial Office of Detention Oversight (ODO) inspections,4 annualcontractor-led compliance inspections by Nakamoto Group, Inc., and theassignment of Custody Management DSMs to cover 54 contract facilities.Inspectors and DSMs report deficiencies to the facility, the ERO Field Officeresponsible for the facility, and ICE headquarters. To correct these deficiencies,ICE’s Detention Standards Compliance Unit, which works independent of thecontract offices, prepares and sends uniform corrective action plans to the EROField Offices and works with them to ensure the deficiencies get resolved. As wepreviously reported, this process is not as effective as intended.5Another path for correcting deficiencies is through the contracts. Though notrequired, detention contracts may include a quality assurance surveillanceplan (QASP). The QASP is a standard template that outlines detailedrequirements for complying with applicable performance standards, includingdetention standards, and potential actions ICE can take when a contractor failsto meet those standards. When facilities are found to be noncompliant, CORsmay submit a Contract Discrepancy Report (Discrepancy Report), whichdocuments the performance issue.After CORs submit Discrepancy Reports, facilities are responsible for correctingdeficiencies or at least preparing a corrective action plan by the identified duedate. If the facility is not compliant, a Discrepancy Report may include arecommendation for financial penalties, such as a deduction in or withholdingof ICE payment to the contractor.6 For example, the QASP states that adeduction may be appropriate when an egregious event or deficiency occurs,such as when a particular deficiency is noted multiple times without correctionor when the contractor failed to resolve a deficiency about which it wasproperly and timely notified. A withholding may be appropriate while thecontractor corrects a deficiency. The contracting officer must approve anywithholdings or deductions.We initiated this review to determine whether ICE is effectively managingdetention facility contracts for its 106 CDF, IGSA, and DIGSA facilities. Thisreport addresses (1) ICE’s failure to use quality assurance tools and imposeconsequences for contract noncompliance; (2) the use of waivers, which maycircumvent detention standards specified in contracts; (3) how the CORs’organizational placement hinders their ability to monitor contracts; and ODO conducts compliance inspections at detention facilities housing detainees for greaterthan 72 hours with an average daily population greater than 10. ODO is under ICE’s Office ofProfessional Responsibility.5 ICE’s Inspections and Monitoring of Detention Facilities Do Not Lead to Sustained Compliance orSystemic Improvements, OIG-18-67, June 20186 Detention facilities cannot recoup a deduction, but can recoup a withholding when theycorrect a deficiency.www.oig.dhs.gov6OIG-19-184

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security (4) CORs’ and DSMs’ lack of direct access to important contract files.Results of InspectionAlthough ICE employs a multilayered system to manage and oversee detentioncontracts, ICE does not adequately hold detention facility contractorsaccountable for not meeting performance standards. ICE fails to consistentlyuse contract-based quality assurance tools, such as by omitting the QASP fromfacility contracts. In fact, only 28 out of 106 contracts we reviewed included theQASP. Because the QASP contains the only documented instructions forpreparing a Discrepancy Report and recommending financial penalties, there isconfusion about whether ICE can issue Discrepancy Reports and imposefinancial consequences absent a QASP. Between October 1, 2015, and June 30,2018, ICE imposed financial penalties on only two occasions, despitedocumenting thousands of instances of the facilities’ failures to comply withdetention standards. Instead of holding facilities accountable through financialpenalties, ICE issued waivers to facilities with deficient conditions, seeking toexempt them from having to comply with certain detention standards. However,ICE has no formal policies and procedures about the waiver process and hasallowed officials without clear authority to grant waivers. ICE also does notensure key stakeholders have access to approved waivers. Further, wedetermined that the organizational placement and overextension of CORsimpede monitoring of facility contracts. Finally, ICE does not adequately shareinformation about ICE detention contracts with key officials, such as CORs andDSMs, which limits their ability to access information necessary to performcore job functions. ICE Does Not Consistently Use Contract-Based QualityAssurance Tools and Impose Consequences for ContractNoncomplianceAs noted, there are two paths for correcting deficiencies: the facilitiesinspection process and the quality assurance tools in the facilities contractsthemselves. With respect to the inspection process, we previously reported thatICE does not adequately follow up on identified deficiencies or consistently holdfacilities accountable for correcting them.7 During our current work, we foundsimilar problems with ICE’s use of contract-based quality assurance tools.Specifically, ICE did not consistently include the QASP in the facility contractswe reviewed, which has led to confusion among CORs about how to issueDiscrepancy Reports. These problems are compounded because ICE does not ICE’s Inspections and Monitoring of Detention Facilities Do Not Lead to Sustained Compliance orSystemic Improvements, OIG-18-67, June 2018www.oig.dhs.gov7OIG-19-187

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security track these reports and rarely imposes financial consequences, even whenidentified deficiencies present significant safety and health risks.Out of 106 contracts we reviewed, only 28 contained the QASP.8 The QASP isespecially important because it contains the only documented instructions forpreparing a Discrepancy Report and recommending financial penalties, wheninformal resolution is not practicable.9 Consequently, when contracts do notcontain the QASP, CORs and contracting officers are left confused as to whatactions they can take when deficiencies are identified. For example, of the 11CORs we interviewed, 5 told us they could issue a Discrepancy Report to afacility that did not have the QASP, while 2 said they could not. Two otherssaid they could issue a Discrepancy Report without the QASP, but they couldnot seek financial penalties for noncompliance. The two remaining CORs toldus they did not know whether they could issue a Discrepancy Report without aQASP.Even where ICE does issue Discrepancy Reports, ICE does not track their useor effectiveness. No office within ICE could provide any data on how manyDiscrepancy Reports are issued to facilities and for what reasons. An ICEofficial from Acquisitions Management explained that his office would have toreview the individual contract files to see whether Discrepancy Reports wereissued and why. The Discrepancy Reports we reviewed involved seriousdeficiencies such as significant understaffing, failure to provide sufficientmental health observation, and inadequate monitoring of detainees withserious criminal histories. However, we have no way of verifying whether any ofthese deficiencies have been corrected.Furthermore, ICE is not imposing financial penalties, even for seriousdeficiencies such as those we found in the Discrepancy Reports. In addition tothe issues flagged by these Discrepancy Reports, from October 2015 to June2018 various inspections and DSMs found 14,003 deficiencies at the 106contract facilities we focused on for this review. These deficiencies includethose that jeopardize the safety and rights of detainees, such as failing to notifyICE about sexual assaults and failing to forward allegations regardingmisconduct of facility staff to ICE ERO. Despite these identified deficiencies,ICE only imposed financial penalties twice. ICE deducted funds from onefacility as a result of a pattern of repeat deficiencies over a 3-year period,primarily related to health care and mental health standards. The otherdeduction was made due to a U.S. Department of Labor order against the Specifically, all 8 CDF and 10 of the 11 DIGSA facilities had a QASP in place, but only 10 of87 non-dedicated IGSA facilities had a QASP.9 The QASP directs the COR to send a Discrepancy Report documenting the deficiencies to thefacility. The facility is required to respond to the Discrepancy Report by a specified date,indicating that either the deficiencies have been corrected or a corrective action plan is inplace.www.oig.dhs.gov8OIG-19-188

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security contractor for underpayment of wages and was not related to any identifieddeficiency. Our review of the corresponding payment data identified about 3.9million in deductions, representing only 0.13 percent of the more than 3billion in total payments to contractors during the same timeframe. ICE did notimpose any withholdings during this timeframe.ICE’s Waiver Process May Allow Contract Facilities toCircumvent Detention Standards and May Inhibit ProperContract OversightInstead of holding facilities accountable through financial penalties, ICEfrequently issued waivers to facilities with deficient conditions, seeking toexempt them from having to comply with certain detention standards.10However, we found that ICE has no formal policies and procedures to governthe waiver process and has allowed ERO officials without clear authority togrant waivers. We also determined that ICE does not ensure key stakeholdershave access to approved waivers. In some cases, officials may violate FederalAcquisition Regulation requirements because they seek to effectuateunauthorized changes to contract terms.Lack of Guidance on the Waiver Process Potentially Exempts Contract Facilitiesfrom Complying with Certain Detention Standards IndefinitelyGenerally, waiver requests result from ICE’s inspections or DSMs’ monitoring.After completing an inspection, inspectors brief the facility on the deficienciesthey find and issue inspection reports. The Detention Standards ComplianceUnit then issues uniform corrective action plans to the ERO Field Offices andDSMs. The Field Offices forward the uniform corrective action plans to thefacilities, work with the facilities to correct the identified deficiencies, andreport those corrective actions to the Detention Standards Compliance Unit.DSMs monitor compliance on a daily basis and report deficiencies to thefacilities, to local ICE Field Offices, and through weekly reports to CustodyManagement.As ICE ERO works with the contractor to resolve the deficiencies, a facility canassert that it could not remedy the deficiency because complying with thestandard can create a hardship, because of a conflict with a state law or a localpolicy, a facility design limitation, or another reason. In these cases, the FieldOffice Director may submit a waiver request to Custody Management, whichapproves or denies the request. We analyzed the 68 waiver requests submitted ICE’s Inspections and Monitoring of Detention Facilities Do Not Lead to Sustained Complianceor Systemic Improvements, OIG-18-67, June 2018www.oig.dhs.gov9OIG-19-1810

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security between September 2016 and July 2018. Custody Management approved 96percent of these requests, including waivers of safety and security standards.11Despite this high approval rate, ICE could not provide us with any guidance onthe waiver process. Key officials admitted there are no policies, procedures,guidance documents, or instructions to explain how to review waiver requests.The only pertinent documents that ICE provided were examples of memorandathat Field Office Directors could use to request waivers of the detentionstandards’ provisions on strip searches. However, the memoranda did notacknowledge the important constitutional and policy interests implicated by afacility’s use of strip searches. ICE officials did not explain how CustodyManagement should handle such waiver requests when a contrary contractualprovision requires compliance with a strip search standard.Further, contract facilities may be exempt from compliance with otherwiseapplicable detention standards indefinitely, as waivers generally do not have anend date and Custody Management does not reassess or review waivers after itapproves them. In our sample of 65 approved waiver requests, only three hadidentified expiration dates; the 62 others had no end date.The Chief of the Detention Standards Compliance Unit within ICE EROCustody Management has drafted written guidance on the waiver submissionand approval process, but has not finalized that document. Without formalwaiver guidance and review processes, ICE may be indefinitely allowingcontract facilities to circumvent detention standards intended to assure thesafety, security, and rights of detainees. A facility’s indefinite exemption fromcertain detention standards raises risks to detainee health and safety that ICEcould reduce by enforcing compliance with those standards. For example,Custody Management granted a waiver authorizing a facility (a CDF) to use 2chlorobenzalmalononitrile (CS gas) instead of the OC (pepper) spray authorizedby the detention standard. According to information contained in the waiverrequest, CS gas is 10 times more toxic than OC spray.12 Another waiver allowsa facility (a DIGSA) to commingle high-custody detainees, who have histories ofserious criminal offenses, with low-custody detainees, who have minor, nonviolent criminal histories or only immigration violations, which is a practice thestandards prohibit in order to protect detainees who may be at risk ofvictimization or assault.13 PBNDS 2008 and PBNDS 2011 organize standards by seven topics: safety, security, order,care, activities, justice, and administration and management. NDS 2000 organizes standardsby three topics: detainee services, health services, and safety and control.12 ICE PBNDS 2011, Part 2 – Security, 2.15 Use of Force and Restraints Section (V)(G)(4) states,“The following devices are not authorized [ ] mace, CN, tear gas, or other chemical agents,except OC spray.”13 ICE PBNDS 2011, Part 2 – Security, 2.2 Custody Classification System requires facilities toavoid commingling low-custody detainees, who have minor, non-violent criminal histories orwww.oig.dhs.gov10OIG-19-1811

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERALDepartment of Homeland Security ERO Officials without Clear Authority Are Granting Waivers That MayUndermine Contract TermsICE’s practice for issuing waivers could violate the Federal AcquisitionRegulation (FAR), which establishes policies and procedures that executiveagencies, including DHS, must use for acquisitions, unless other legalauthority removes an acquisition from the FAR’s coverage. Under the FAR,“only contracting officers acting within the scope of their authority areempowered to execute contract modifications.”14 To prevent others fromexercising authority expressly reserved for contracting officers, the FARexplains that other Federal personnel shall not “[a]ct in such a manner as tocause the contractor to believe that they have authority to bind theGovernment.”15 ICE asserts that only its CDFs, not its DIGSAs or IGSAs, areacquisitions governed by the FAR. However, Acquisitions Managementprocurement guidance stipulates that, in handling DIGSA and IGSA issues,contracting officers “should utilize applicable FAR principles and clauses thatare in the Government’s best interest to the maximum extent possible.”16Despite these FAR provisions and this guidance, a senior official told us thatthe Assistant Director for Custody Management has the authority to act onwaiver requests. The Assistant Director has, in turn, orally delegated authorityto decide waiver requests to the Deputy Assistant Director for CustodyManagement. However, Custody Management did not provide anydocumentation of this authority, delegated or otherwise, to grant waivers.According to the same official, the detention standards are ICE policies and thecurrent waiver approval process is sufficient. This position does notacknowledge that ICE contractually requires facilities to comply with detentionstandards, and that only the contracting officer — not the Assistant Director orthe Deputy Assistant Director — can modify those contract terms.Through their approval of waivers, ERO officials without the authority tomodify contracts have sought to remove certain detention standards fromoversight, even though

Facility Contractors Accountable for Failing to Meet Performance Standards January 29, 2019 Why We Did This Inspection U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) contracts with 106 detention facilities to detain removable aliens. In this review we sought to determine whether ICE contracting tools hold immigration detention

Present ICE Analysis in Environmental Document 54 Scoping Activities 55 ICE Analysis Analysis 56 ICE Analysis Conclusions 57 . Presenting the ICE Analysis 59 The ICE Analysis Presentation (Other Information) 60 Typical ICE Analysis Outline 61 ICE Analysis for Categorical Exclusions (CE) 62 STAGE III: Mitigation ICE Analysis Mitigation 47 .

The ice-storage box is the destination point where the ice will accummulate via the ice-delivery hose. An ice-level sensor installed in the storage box halts ice production when the box is full. The ice-storage box should be able to hold water and have at least 2" (51mm) of insulation to keep the ice frozen as long as

Department of Labor (DOL) is pleased to present the OIG Investigations Newsletter, containing a bimonthly summary of selected investigative accomplishments. The OIG conducts criminal, civil, and administrative investigations into alleged violations of federal laws relating to DOL programs, operations, and personnel. In addition, the OIG conducts

Here’s why: There’s a difference between sea ice and land ice. Antarctica’s land ice has been melting at an alarming rate. Sea ice is frozen, floating seawater, while land ice (called glaciers or ice sheets) is ice that’s accumulated over time on land. Overall, Antarctic sea ice has been stable (so far) — but that doesn’t contradict the

670 I ice fatete, ice-dancing tikhal parih laam le lehnak. ice-fall n a hraap zetmi vur ih khuh mi hmun, lole vur tla-ser. ice-field n vur ih khuhmi hmun kaupi. ice-floe n ti parih a phuan mi tikhal tleep: In spring the ice-floes break up. ice-free adj (of horbour) tikhal um lo. ice hockey tikhal parih hockey lehnak (hockey bawhlung fung ih thawi).

Surface Ice Rescue Student Guide Page 5 5. Thaw Hole - A vertical hole formed when surface holes melt through to the water below. 6. Ice Crack - Any fissure or break in the ice that has not caused the ice to be separated. 7. Refrozen Ice - Ice that has frozen after melting has taken place. 8. Layered Ice - Striped in appearance, it is constructed from many layers of frozen and

national ice cream competition results 2020 national ice cream champion 2020 best of flavour 2020 best of vanilla 2020 jim valenti senior shield dairy ice cream vanilla equi’s ice cream ralph jobes shield open flavour pistachio crunch luciano di meo dairy ice cream vanilla equi’s ice cream alternative class - glass trophy gold medal .

11 91 Large walrus herd on ice floe photo 11 92 Large walrus herd on ice floe photo 11 93 Large walrus herd on ice floe photo Dupe is 19.196. 2 copies 11 94 Walrus herd on ice floe photo 11 95 Two walrus on ice floe photo 11 96 Two walrus on ice floe photo 11 97 One walrus on ice floe photo