Pay: What Motivates Financial Services Executives? - PwC

www.pwc.com/financial servicesPay: what motivatesfinancial services executives?The psychology of incentivesA global study intothe impact of payand incentives onsenior executives.August 2012

ContentsExecutive summary6Design recommendations7It’s all about incentives8But do they work?10What do executives really think?12Executives are risk-averse14Complexity and ambiguity destroy value16The longer you have to wait, the less it’s worth18It’s all relative – fairness is fundamental20There’s more to work than money22LTIPs motivate through recognition as much as incentive24What does it mean for reward?26Looking to the future302Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives

About our studyThis research was carried out by PwC1in conjunction with the London Schoolof Economics and Political Scienceduring November/December 2011. 1,106participants took part in the study, 81%of whom were male and 19% female. 187worked in the financial sector (22% ofwhom were female).The executives had a wide range ofsenior roles in various sectors and werecategorised into three earnings’ bands of 350,000 and under (66% of participants),between 350,000 and 725,000 (24%of participants), and over 725,000 (10%of participants).1PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of itsmember firms, each of which is a separate legal entity.Participants1,1061,106 executives participated in the survey81%Male24%7%8%28%10%7%16%From a total of 7 regionsFemale19%66%Earned 350,000 or under24%Earned 350,000 – 725,00010%Earned 725,000 or morePay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives3

Figure 1Figure 2Participants by regionParticipants by countryNorth America(28%)CEE (7%)Africa (7%)Middle East(8%)SOCAT(10%)Western Europe(24%)Asia Pacific(16%)Q10: Where are you based?Base: All respondents India83Mexico30Middle East18Netherlands55Poland33Eire29Russia45South : Where are you based? Base: All respondents (1,106)4Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives100150200250

Financial services pay underthe microscopeOver the past few years pay practices inthe financial services sector have comeunder intense scrutiny. Driven partlyby the belief that the banking crisiswas in part caused by excessive shortterm risk-taking encouraged by a bonusculture, regulators, governments andshareholders in many countries havepushed for changes in reward in the sector,and in particular for an ever‑greateremphasis on longer term incentives.Last year, PwC (UK), in conjunctionwith the London School of Economics,carried out a fascinating study that wasdesigned to test how company executivesmake decisions about pay. The resultingreport, The Psychology of Incentives, wasa revealing indictment of the currentlong-term incentives’ model and showedwhy they often don’t work in the way theywere intended.Our next step was to discover if the sameresults hold true for executives, globally,and the study was extended to examinethe behaviour of over 1,000 executivesin 43 countries and a wide range ofsectors including financial services. Thisworldwide study allowed us to assesswhether the age and nationality ofexecutives, and the sector in which theywork, has any impact on the way they thinkabout pay, and incentives in particular.the sector. Overall, the conclusions suggestthat the favoured tools of many regulatorsand shareholders – deferral and oftencomplex long-term incentive structures –may not produce the hoped-for results.This study illustrates much of what’swrong with executive pay, but also whatworks. We hope it will prove an importantcontribution to the debate.One of the strongest messages to comeout of the research is that financialservices executives aren’t unique. Muchof the debate about executive pay in thewake of the global financial crisis wasfocused around the banking sector, butit’s clear from our research that executivesin FS think in a similar way to those inany other industry. The same rules andbehaviours apply. However, the findingshave particular resonance for FS, given theeconomic and regulatory forces at play inPay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives5

Executive summaryKey findingsExecutives arerisk‑averseComplexityand ambiguitydestroy valueThe longer youhave to wait theless it’s worthIt’s all relative– fairness isfundamentalPeople don’t justwork for moneyThe key motivationof a long-termincentive plan isrecognitionMost FS executiveschose fixed pay overbonus of a higher value– only 24% chose thehigher risk bonus.Fifty percent moreexecutives choose aclearer pay package thana more ambiguous one ofthe same or potentiallyhigher value.Executives valuedeferred paysignificantly below itseconomic or accountingvalue – a deferred bonusis typically discountedby around 50% overthree years.Most executives wouldchoose to be paid lessin absolute terms butmore than their peers –only a quarter choose ahigher absolute amount,but which is less thantheir peers.FS executives wouldtake a 30% pay cut fortheir ideal job, verysimilar to the overallaverage of 28%.Fewer than half ofexecutives thinkthat their long-termincentive plan is aneffective incentive.Discounts areparticularly high inAsia and Latin America,with deferred paymentsbeing discounted by upto two-thirds in the eyesof executives.Fairness is much lessimportant in Brazil andChina than in otherterritories, but you can’tgeneralise about BRICs,as it is most importantin India.The result is veryconsistent, globally, withthe lowest cut being 24%(India) and the highest35% (USA).But two-thirds ofparticipants valuethe opportunity toparticipate in their firm’slong-term incentive plan.FS executives wereactually more risk‑aversethan the overallpopulation – nearly 30%of non-FS executiveswere prepared to takethe riskier bonus.6Two-thirds moreexecutives prefer aninternal measure theycan control (such asprofit) as opposed toan external relativemeasure (such as totalshareholder return).Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives

Design recommendationsPerformance pay hasa cost – be sure you’regetting valueKeep it short, sweetand simpleOne size does notfit all – know yourpeople and pay themaccordinglyMoney is only partof the deal – andrecognition mattersas well as financialincentivesBe realistic abouthow variable pay canbe from year to yearPerformance pay isdiscounted compared tofixed pay by around 10% forcash bonuses and 50% ormore for deferred bonusesand long-term incentives.Be thoughtful about wheredeferral and long-termincentives are operated, andrestrict their use to wherethere is a clear payback.Be cautious about assumingyour pay design will workglobally – attitudes toincentive pay are verydifferent in developed andemerging markets.Pay is as much aboutfairness and recognition as itis about incentives.Only a limited number ofexecutives will be motivatedby highly leveraged andvolatile pay packages – lessvolatility may mean you canpay less.Be sure the inefficiencyof paying your peoplethrough performance payis outweighed by benefitssuch as the incentive toperform better or the costflexibility provided.Whenever possible, go for thesimpler option – requiringexecutives to hold sharesmay be a better approachthan plans with complexperformance conditions.Think about how to providechoice and flexibility inpay programmes – higherperceived value may outweighthe administrative cost.Simpler plans can achieve therecognition benefit with lessdiscount to perceived value.If incentives form themajority of the total package,accept that they won’t be zerovery often.Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives7

It’s all about incentives8Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives

‘ Globally, there is an increasing trend for companies to turntowards incentive pay, for a variety of reasons.’Incentive-based pay for executives andsenior management has become almostubiquitous over the past two decades. Thetransformation in developed economieshas been largely driven by the desire toalign the interests of management andshareholders on the assumption thatexecutives will perform better if they areheavily incentivised. The financial crisisand subsequent recession in manydeveloped countries added anotherdimension to the debate. The crisishas resulted in an intense scrutiny ofexecutive pay, particularly in financialservices. Interestingly, rather thanrejecting performance pay, regulatorshave demanded more of it in morecomplex forms.This is not a uniquely Westernphenomenon. Globally, there is anincreasing trend for companies to turntowards incentive pay, for a varietyof reasons. Performance pay providesflexibility in uncertain times. Governancehas gone global, and shareholders in manymarkets have become more activein pressing companies to link pay toperformance. There’s an element ofdeveloping economies choosing to adoptWestern compensation practices in orderto compete with Western employersthat have entered their market. Andemployment market forces have alsoplayed their part. The intense competitionfor talented executives in the fastgrowing BRIC countries, for instance, hasdriven up reward packages and in thosecountries with high churn rates, longterm incentives are seen as a vital tool inretaining the best. The theme of the lastdecade in financial services has been globalconvergence – of pay levels and structures– for an internationally mobile group ofsenior executives.The end result is that incentives andperformance-based equity are the paystructures of choice in financial services.Long-term incentive plans (LTIPs) havebecome evermore complicated, oftencombined with clawback arrangements,net holding requirements andperformance‑based deferrals of cashbonuses in response to shareholder andregulatory pressures, and in an attempt toalign pay to business performance.Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives9

‘ A s the saying goes, the definition of insanity is doing the samething over again and expecting a different result.’But do they work?The fundamental question, though, iswhether incentives actually do the jobthey’re intended to do.Reward design tends to assume that peoplemake rational decisions – but is that reallythe case? The issue of performance payhas polarised academics for some time,but questions are increasingly being askedabout its effectiveness. In those marketsthat have used them longest it’s alsobecoming increasingly clear that there issomething seriously wrong with LTIPs.Companies invest an enormous amountinto these plans, but the response fromexecutives can rarely be said to justifythe cost.10Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentivesThe recent financial crisis and theperception that bonuses played a rolein causing it has led to a renewed focuson performance pay. But even now, the‘solutions’ put forward are still based on theassumption that performance-related payworks, and that the answer is to structureit differently, to have more sophisticatedpayout formulae and to defer pay overlonger periods.As the saying goes, the definition ofinsanity is doing the same thing over againand expecting a different result. Given thatthis ‘age of governance’ has not coincidedwith a period of conspicuous success forthe Western economies that gave birth toit, it’s surely valid to ask some challengingquestions about pay for performance, andin particular, LTIPs. And will the currentchanges in financial services pay modelsin a number of countries largely driven byregulatory requirements, make mattersbetter or worse?

‘ It’s surely valid to ask some challengingquestions about pay for performance, andin particular, LTIPs.’Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives11

What do executives really think?12Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives

‘ Are BRICs different from developed economies? Are men different from women? Do executivesfrom different sectors vary in their attitudes?’Our latest research, in conjunction withDr Alexander Pepper at the London Schoolof Economics and Political Science, seeksto provide the evidence that’s needed abouthow executives – the group of people whoseperformance is meant to be improved byincentive pay – react to incentives.This research follows on from a joint studyof around 100 UK executives, which led toour 2011 research report and which led usto question the effectiveness of LTIPs andto set out a series of design principles thatcompanies should follow to get the bestvalue for money.We wanted to find out if the results heldglobally for all executives and whetherthere are key differences in financialservices. Are BRICs different fromdeveloped economies? Are men differentfrom women? Do executives from differentsectors vary in their attitudes?So we worked with Dr Pepper to extendthe study. The research involved askingsenior executives to complete a structuredinterview questionnaire, based on wellestablished techniques of behaviouraleconomics, which explored the tradeoffsthat individuals make between risk,reward, certainty and time. Our panel ofparticipants comprised 1,106 executives in43 countries, within a wide range of seniorroles, companies and industries; of these187, were from financial services.We analysed the responses of ourparticipants by gender, by age and bycountry. We also examined whetherexecutives in the financial services sector– who are more familiar with the financialtechnicalities of incentivised pay – reactany differently than executives in othersectors. The results reveal a number ofcommon behavioural traits, which showclearly that executives don’t necessarilythink in the way that many incentiveschemes assume.So what did we find? Broadly, the researchsupports the findings of the UK study,although there are some fascinatingvariations by geography and gender. Ourreport shows that there are many featuresof deferred pay and LTIPs that are likely tolimit their effectiveness. This should giveregulators pause for thought. In the EU inparticular, regulation has given birth toprogrammes of bewildering complexity.Our research suggests it’s unlikely thatthese will influence behaviour to preventthe next crisis.To get best value from these plans, it’simportant to base designs on evidencerather than conjecture, and to use ourlatest understanding of behavioural scienceto come up with performance plans thatactually do what they are meant to do.Performance pay is with us – we need tomake it work.Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives13

Executives are risk-averse“ It’s a given that employees willact to maximise anticipatedreward. I will always choosemore over less, now over later,and certainty over uncertainty.”Executives’ attitude to risk was assessedwith two questions, which askedparticipants to choose between a smaller,certain amount of money and a 50% chanceof receiving a larger sum with a higherexpected value (the amounts were adjustedto take account of the executives’ currentpay). The first question was framed as agamble, the second as a bonus opportunity:Male executive, MalaysiaAttitude to riskWhich would you prefer as aone-off gamble?a. 50% chance of 5,250 (or nothing)b. 2,250 for certainc. Indifferent to a) or b)Given that the annual bonus of a seniorexecutive of a large company is around 45,000, which would you prefer?a. 50% chance of receiving a bonus of 90,000 (or nothing)b. 41,250 for certainc. Indifferent to a) or b)14Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentivesIt’s clear from the results that risk‑aversionincreases with the amount at stake, andthat people will tend to choose morecertain but less generous amounts overless certain but more generous outcomes.When offered a smaller certain amount ora gamble for a larger sum, just over half ofall respondents (51%) chose the certainamount. This seems to be a universalpreference; contrary to popular perception,executives working in the financial sectorwere slightly more risk-averse than thegeneral population.Participants in Africa were the mostrisk‑averse, with 61% choosing the certainsum. This increased to nearly two-thirds(64%) when the amount was increased.There was only one region – SouthAmerica – where more participants chosethe gamble over the certain amount, andeven in this case their preference switchedwhen a larger amount was offered as abonus opportunity rather than a salary. Inall other cases, the majority preferred thesmaller, safer option, or were indifferentbetween the two choices.

But while it’s true to say that the majorityof executives are risk-averse, a closerlook at the results give the clear messagethat one size doesn’t fit all. Overall, morethan a quarter (28%) of participants wereprepared to gamble a certain sum for apotentially higher bonus. In other words, asizeable proportion of executives are activerisk seekers.Prepared to take a gamble?PopulationProportion prepared toswap a certain sum of 41,250 for a variablebonus of up to 90,000Overall28%Women23%Men30%UK and Australia15%Netherlands,35% Brazil, ChinaFinancial services24%Financial services was more risk‑aversethan other industries. This goes againstthe popular perception of a risk-seekingindustry. But this is perhaps a sign ofthe times: with the bonus pool outlookuncertain, fixed pay is taking on a higherperceived value. This is reflected in recent‘rebalancing’ exercises in the sector.The research confirms the widely heldview that women are more risk-averse thanmen. But there were also some surprises.Executives over the age of 60 were themost likely to take a gamble, while thoseaged 40–60 were least likely to risk thesmaller, certain amount for the chance ofa bigger win. Perhaps this is because olderexecutives are more financially secure andhave fewer commitments. Few would besurprised that executives in the developedeconomies of the UK and Australia are morerisk-averse than in the rapidly growingBrazil and China – but the Dutch appear tolike a gamble too.This reinforces the point that companiesneed to know their audience. Incentives aremore likely to work for risk-takers, but noteveryone likes risk to the same degree. Ourstudy shows that most employees demand apremium of over 10% to take pay in bonusrather than salary, meaning that bonus isa relatively expensive way of paying manyexecutives. Companies need to be surethat what they get in terms of improvedperformance and increased flexibility ofcost is worth what they’repaying. Conversely, firms rebalancingfrom variable to fixed should be looking tocapture some of the perceived value benefitby cutting costs overall.One size doesn’t fit all51%When offered a smallercertain amount or a gamblefor a larger sum, just overhalf of all respondents (51%)chose the certain amount60 Executives over the age of 60were the most likely to takea gamble40 – 60Those aged 40 – 60 wereleast likely to risk the smallercertain amount for thechance of a bigger win24%Around a quarter (24%) of FSparticipants were preparedto gamble a certain sum for apotentially higher bonus.Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives15

Complexity and ambiguitydestroy value“ I don’t assign any value to myshare allocations. I considerthem in the same way as acompany lottery ticket.”Female executive, AustraliaThe study tested attitudes to uncertaintywith three questions. The first was framedas a straightforward gamble – a choicebetween a 50% chance of winning acertain amount, or a chance of winningthe same amount where the probabilitywas unknown but could be anythingbetween 25% and 75%. The second andthird questions were framed as share andbonus awards:Impact of complexityGiven that the annual bonus of a seniorexecutive in a large company is around 45,000 and the median long-termincentive award is around 67,500 ayear, which would you prefer?a. A guaranteed bonus of 45,000 payablein three years’ timeb. A guaranteed bonus of 20,000 sharesdeliverable in three years’ time. Thecurrent share price is 2.25 and in thepast 12 months the share price hasfluctuated between 1.12 and 3.37c. Indifferent between a) and b)Given the same facts, which wouldyou prefer?a. A cash bonus of up to 52,500, whichwill be paid in three years’ time if thecompany’s earnings per share growsat least 3% more than the RetailPrice Indexb. A bonus of up to 23,350 sharesdeliverable in three years’ time,depending on the company’s relativetotal shareholder return over the periodwhen compared against a basket ofcomparable companiesc. Indifferent between a) and b)16Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives

Executives clearly wanted to understandthe rules of the game. Fifty percent moreexecutives wanted to know the probabilityof the gamble they were taking than wereprepared to bet on a situation where theprobability could be higher or lower. Andoverall, two-thirds more favoured a cashplan based on a condition that was internalto their organisation (earnings per share)over the more ambiguous share plan basedon relative total shareholder return.Attitudes to deferred shares versus deferredcash were quite varied. Overall, there wasa slight preference for deferred cash, witharound a fifth more executives preferringcash over shares, although there weresome significant differences by country.FS executives were no different from thegeneral population of respondents.Cash or shares?Prefer sharesPrefer cashBrazil, China, India, USAustralia, Netherlands,Switzerland, UKIt’s interesting that executives in the BRICnations – where it’s often assumed a ‘hereand now’ culture pervades – tended toprefer shares over cash. Of course, boththe cash and the shares are deferred, so ifthey have to be locked into the deferral,perhaps they are inherently more optimisticabout the upside that shares provide.FS executives were fairly evenly split,with cash just slightly more popular. Itis interesting that the negative impact ofrecent share price falls on deferrals has notskewed preferences more towards cash.Once again, the over-60s belied the imageof conservative sexagenarians – they werefar more willing to take on uncertainty inexchange for a higher upside. Only 29% ofthose aged between 60 and 64, and 32% ofthose over 65, chose the smaller cash bonusover shares.The message here is that uncertaintyand complexity are a turn-off for mostpeople. In almost every case, participantsselected the less complicated option. Themore complicated the reward, the morelikely they were to choose the smallerbut more certain award. Given that mostLTIPs are invariably complicated, there isa clear warning here that an unnecessarilycomplicated system is unlikely to producethe best results. Financial servicesregulators take note. The EU in particularhas indulged in some arcane debates aboutcash – shares mix, deferral structuresand retention periods. All this complexityis simply reducing the effectiveness ofprogrammes. In our view, FS firms shouldbe focusing on what people are gettingpaid for (risk‑adjusted performance) ratherthan the form in which they receive it.But remember that complexity is relative– if executives deal with the metrics andreporting information that are linked totheir awards as a regular part of theirjob, it will appear simpler to them than itwould to someone who only comes acrossthese measures when it comes to assessingtheir performance.Cash or shares?Prefer landsSwitzerlandUKPrefer cashAustraliaIt’s interesting that executives in the BRIC nations, where it’s often assumed a‘here and now’ culture pervades, tended to prefer shares over cash. Of course,both the cash and the shares are deferred, so if they have to be locked into thedeferral, perhaps they are inherently more optimistic about the upside thatshares provide.Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives17

The longer you have to wait,the less it’s worth“ People need to feel that theirefforts are being rewarded in aconcrete way.”Female executive, Poland18Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentivesExecutives’ attitude to time was assessedusing three questions that compared thepossibility of receiving a certain amounttoday, or a larger sum in three years’ time.Some of the questions were framed in sucha way that it was possible to estimate thediscount rates that participants attach tothe deferred payments.Given the same facts as above, whichwould you prefer?a. 75% chance of receiving a bonus of 56,250 tomorrow, otherwise nothingb. 75% chance of receiving abonus of 90,000 in three years,otherwise nothingc. Indifferent between a) and b)Impact of time on perceived valueYou’re invited to take part in a one-offgamble. Which of the following choiceswould you prefer?a. 75% chance of winning 2,250tomorrow (25% chance of nothing)b. 75% chance of winning 5,250 in threeyears (25% chance of nothing)c. Indifferent to a) and(b)The results show that when there isuncertainty about whether a payment willbe received, executives across the globeapply discount rates to deferred paymentsthat are massively in excess of economicdiscount rates. This is an illustration of thedifference between financial theory andreal-life behavioural economics. Financialtheory says that individuals shoulddiscount at rates consistent with the returnon comparably risky cash flows, whichin this case should be near the ‘risk‑free’interest rate of around 5% per annum(used in accounting valuations of LTIPs).The study, though, shows that executivesmore typically discount at around 30% perannum – this is the economics of ‘eat, drinkand be merry, for tomorrow we may die’.Given that the median long-termincentive award of a senior executive ofa large company is around 67,500 ayear, which of the following choices wouldyou prefer?a. 75% chance of receiving a bonusof 37,500 tomorrow (25% chanceof nothing)b. 75% chance of receiving a bonus of 90,000 in three years (25% chanceof nothing)c. Indifferent between a) and b)

Estimated discountratePerceived value of 1 deferredpro rata overthree yearsAllEuropeNorthAmerica31%20%31% 0.50 0.65 0.50Asia- Central & South &Pacific Eastern CentralEurope America42%26%45% 0.37 0.56 0.34MiddleEastAfrica Financialservices37%40%32% 0.43 0.39 0.49* For example, with a discount factor of 31% pa a three‑year phased deferral of 1 will have a perceived value of: 1 x (1/3) x [(1/1.31) (1/1.31)2 (1/1.31)3] 0.50 ]Younger executives tended to discount ata higher rate than others (those under theage of 39 applied a 45% discount rate).They have more immediate financial needsand are more likely to value money todayover money tomorrow; those between theages of 55 and 59 applied a rate of 22%.The discount rates applied also varied fromcountry to country. The table above showsthe implied annual discount rate applied todeferred awards. The second row shows theresulting perceived value of 1 of bonus,which is paid out over one, two and threeyears, the typical deferral structureendorsed by financial services regulators.This tendency to discount future awardsheavily is replicated across all sectors.It might be safe to assume that anyoneworking in the financial sector would beused to deferral and might be more likelyto discount at a reasonable rate, giventhat they have a better understanding ofdiscounting than most, but this isn’t thecase. The discount rates that participantsmentally apply to an amount received inthree years’ time are consistent for thoseworking in financial services and thoseworking in other sectors.Shareholders, regulators and corporategovernance bodies have generallyassumed that deferred bonuses are apowerful way of influencing behaviourand aligning executives with shareholdersand prudent risk-taking. These findingsplace a significant question mark overthe effectiveness of the deferral model.The best-case scenario, in Europe, is thatdeferral results in a discount of one‑third inperceived value. But in emerging marketsthe discount is more like two-thirds. Thisseems to be a very heavy price to pay.A clear consequence is that as deferralincreases, we should expect upwardpressure on the level of compensation.We question whether some regulators haveadopted a model that significantly inhibitspay efficiency. What’s better, to defer 1bnand have it written down to 500m inexecutives’ eyes, or to pay instead, 500mup front and add the other 500m straightto capital or dividends?Typical discounting 0.49FS executives typically value each of deferralat 0.49– this is the economics of ‘eat, drinkand be merry, for tomorrow we may die’Pay: what motivates financial services executives? The psychology of incentives19

It’s all relative –fairness is fundamental“ It really becomes a problem whenpeople start to talk. If you don’tknow what people earn, it’s nota problem.”Male executive, UKOne of the strongest messages to come outof the research was that the overridingconcern for executives is whether their payis comparable against their peer group. Theresults suggest strongly that executives arecontent as long as they are paid what theyconsider to be ‘fair’ within the hierarchyof their own company, and comparablyagainst those on a similar level incompetitor companies, to the extent that italmost becomes irrelevant how much theyare paid. It seems to be deeply ingrainedwithin human psychology to compareourselves with others.The executives were asked this question:Testing attitudes to fairness throughthe relativity questionJean and Jacques are two friends leavingbusiness school. Jean is offered a job tojoin the senior management of Compa

The key motivation of a long-term incentive plan is recognition Fewer than half of executives think that their long-term incentive plan is an effective incentive. But two-thirds of participants value the opportunity to participate in their firm's long-term incentive plan. Executives are risk-averse Most FS executives chose fixed pay over

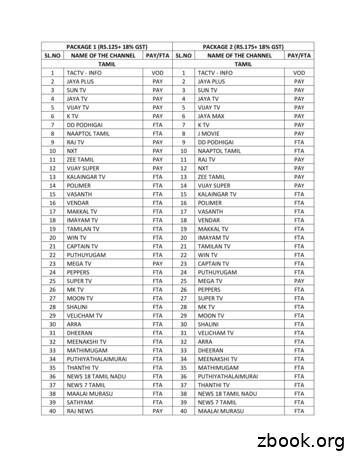

3 sun tv pay 3 sun tv pay 4 jaya tv pay 4 jaya tv pay 5 vijay tv pay 5 vijay tv pay . 70 dd sports fta 71 nat geo people pay 71 star sports 1 tamil pay 72 ndtv good times pay 72 sony six pay 73 fox life pay . 131 kairali fta 134 france 24 fta 132 amrita fta 135 dw tv fta 133 pepole fta 136 russia today fta .

50 sun music pay 101 cartoon network pay 152 gemini movies pay 51 sun news pay 102 chintu pay 153 gemini music pay 52 sun tv pay 103 chitiram fta 154 gemini tv pay 53 super tv fta 104 chutti pay 155 maa gold pay kids hindi news package 2 (rs.175 18% gst) - 300 channels tamil english news infotainment sports telugu

Pay" by that number, e.g. if paying one week's pay plus two weeks holiday pay, deduct three times the "Free Pay" from the total pay to arrive at the taxable pay for that three week period. If the code is higher than those used in the Tables, the "Free Pay" may be determined by adding the Free Pay from two codes together, e.g. Code 1800

Pay Structure Elements Pay Structure Includes: Pay Schedules o Sets of Pay Grades, multiple markets grouped (geography, industry, etc). Pay Grades o a label for a group of jobs with similar relative internal worth. o associated with a pay range. Pay Ranges o the upper and lower bounds of compensation.

These pay scales come into effect from 1.1.2006. 9. Pay Scales and Pay Fixation Formula: a. The Pay Scales prescribed for UGC Revised Pay Scales 2006 as per Fitment Tables annexed shall be implemented. b. The pay of all eligible university and college teachers in the UGC Scales of Pay as on 1.1.2006 shall be fixed at the corresponding pay inFile Size: 421KB

5th CPC Post/Grade and Pay scale w.e.f. 1.1.1996 6th Central Pay Commission w.e.f. 1.1.2006 GRADE SCALE Name of Pay Band/Scale Pay Bands/ Scale Grade Pay . Entry Pay in the revised pay structure for direct rec

Ordinary rate of pay (daily pay) Monthly pay (e.g., minimum wage) / number of working days ordinary rate of pay RM1,000 / 26 days RM 38.46 Hourly rate pay Daily pay / normal hours of work hourly rate pay RM 38.46 / 8 hours RM 4.80 Overtime work during normal day 1.5 x hourly rate pay overtime work 1.5 x RM4.80 RM7.20

Manage Bill Pay Accounts You can view and manage your additional Pay from Accounts. Add New Account Your institution has to approve new pay from accounts. Bill Pay Accounts You can view a list of pending and approved pay from accounts. You can: Change the Nickname. Change the Default Pay From Account. Delete the pay from account.