Subsidised Affordable Rental Housing: Lessons From Australia And Overseas

Subsidised affordablerental housing: lessonsfrom Australia andoverseasauthored bySteven Rowley, Amity James, Catherine Gilbert,Nicole Gurran, Rachel Ong, Peter Phibbs,David Rosen and Christine Whiteheadfor theAustralian Housing and UrbanResearch Instituteat Curtin Universityat The University of SydneyAugust 2016AHURI Final Report No. 267ISSN: 1834-7223ISBN: 978-1-925334-29-6

AuthorsRowley, StevenCurtin UniversityJames, AmityCurtin UniversityGilbert, CatherineThe University of SydneyGurran, NicoleThe University of SydneyOng, RachelCurtin UniversityPhibbs, PeterThe University of SydneyRosen, DavidDavid Paul Rosen and AssociatesWhitehead, ChristineLondon School of EconomicsTitleSubsidised affordable rental housing: lessons from Australia andoverseasISBN978-1-925334-29-6FormatPDFKey wordssubsidised affordable rental housing, housing affordability,institutional investmentEditorAnne BadenhorstPublisherAustralian Housing and Urban Research Institute LimitedMelbourne, AustraliaDOIdoi:10.18408/ahuri-8104301SeriesAHURI Final Report; no. 267ISSN1834-7223Preferred citationRowley, S., James, A., Gilbert, C., Gurran, N., Ong, R., Phibbs,P., Rosen, D. and Whitehead, C. (2016) Subsidised affordablerental housing: lessons from Australia and overseas, AHURIFinal Report No. 267, Australian Housing and Urban ResearchInstitute, Melbourne, http://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/finalreports/267, doi:10.18408/ahuri-8104301.[Add the date that you accessed this report: DD MM YYYY].AHURI National Officei

AHURIAHURI is a national independent research network with an expert not-for-profitresearch management company, AHURI Limited, at its centre.AHURI has a public good mission to deliver high quality research that influencespolicy development to improve the housing and urban environments of all Australians.Through active engagement, AHURI’s work informs the policies and practices ofgovernments and the housing and urban development industries, and stimulatesdebate in the broader Australian community.AHURI undertakes evidence-based policy development on a range of issues,including: housing and labour markets, urban growth and renewal, planning andinfrastructure development, housing supply and affordability, homelessness,economic productivity, and social cohesion and wellbeing.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis material was produced with funding from the Australian Government and stateand territory governments. AHURI Limited gratefully acknowledges the financial andother support it has received from these governments, without which this work wouldnot have been possible.AHURI Limited also gratefully acknowledges the contributions, both financial and inkind, of its university research partners who have helped make the completion of thismaterial possible.DISCLAIMERThe opinions in this report reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarilyreflect those of AHURI Limited, its Board or its funding organisations. No responsibilityis accepted by AHURI Limited, its Board or funders for the accuracy or omission ofany statement, opinion, advice or information in this publication.AHURI JOURNALAHURI Final Report journal series is a refereed series presenting the results oforiginal research to a diverse readership of policy-makers, researchers andpractitioners.PEER REVIEW STATEMENTAn objective assessment of reports published in the AHURI journal series by carefullyselected experts in the field ensures that material published is of the highest quality.The AHURI journal series employs a double-blind peer review of the full report, whereanonymity is strictly observed between authors and referees.ii

COPYRIGHT Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited 2016This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0International License, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.iii

CONTENTSLIST OF TABLES .VIILIST OF FIGURES . IXACRONYMS . XEXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 11INTRODUCTION . 71.1Research questions and methodology . 71.1.1 Research questions and conceptual framework . 71.1.2 Conceptual framework . 71.1.3 Methodology . 91.2Affordable rental housing in Australia . 101.2.1 Federal and state housing assistance . 111.2.2 The need to expand the affordable rental housing sector in Australia . 121.2.3 Private investment in the supply of affordable rental housing . 131.2.4 Current directions in federal and state affordable housing policy. 131.3Subsidising affordable housing: Australian and international research . 141.3.1 Learning from international approaches . 151.3.2 Overview of international experience . 151.3.3 Subsidies for private investment in affordable rental housing . 161.42Summary and implications . 21NATIONAL RENTAL AFFORDABILITY SCHEME: POLICY MECHANISM. 222.1Mechanics of the scheme . 222.1.1 Eligible tenants . 232.1.2 Incentive distribution . 242.1.3 Conditions of allocation . 242.1.4 Application process . 242.2Discontinuation of NRAS. 253NRAS: SPATIAL OUTCOMES . 283.1What was delivered up to June 2015? . 283.2Understanding the distribution of NRAS incentives . 293.2.1 Geographic distribution of incentives. 303.2.2 Changes to the spatial distribution of total incentives . 313.2.3 Analysing the spatial distribution: a composite measure . 313.2.4 Characteristics of typical suburbs using the composite measures . 353.3Where are NRAS dwellings being produced? . 363.3.1 Spatial distribution of dwellings across metropolitan regions . 373.3.2 Socio-economic characteristics of metropolitan suburbs receiving NRASdwellings . 423.3.3 Investment potential characteristics of metropolitan suburbs receivingNRAS dwellings . 433.3.4 Delivery of NRAS dwellings in regional suburbs . 43iv

3.3.5 Has the distribution of NRAS dwellings achieved the scheme objectives? 454NRAS: AFFORDABILITY OUTCOMES. 464.14.2Impact of the 20 per cent rent reduction on housing affordability . 47Impact of NRAS on housing affordability for eligible tenants . 494.3Were NRAS dwellings targeted effectively? . 524.4University-based accommodation . 554.55Summary of affordability outcomes . 57SUBSIDISED AFFORDABLE RENTAL PROGRAMS IN THE UNITEDSTATES AND ENGLAND: OUTCOMES AND LESSONS. 595.1Low Income Housing Tax Credits (United States) . 595.1.1 Allocation of LIHTCs . 595.1.2 Investment structure . 605.1.3 Investment returns . 615.1.4 LIHTC program affordability structure . 625.1.5 LIHTC program outcomes . 625.1.6 Summary . 635.2Affordable Rents regime (England, United Kingdom) . 635.2.1 The mechanics of the Affordable Rents regime . 655.2.2 Affordable Rents regime affordability structure . 655.2.3 Affordable Rents regime outcomes . 665.3What can Australia learn from international approaches to subsidised rentalhousing supply? . 705.3.1 Diversity of product delivery . 705.3.2 Defining affordable rent and incorporating housing assistance. 7165.3.3 Spatial patterns of delivery and housing mix . 71THE FUTURE DELIVERY OF SUBSIDISED RENTAL HOUSING INAUSTRALIA . 736.1Advantages and disadvantages of NRAS. 736.2Moving towards a new model of subsidised affordable rental dwellings . 756.2.1 Clear, measurable and achievable objectives . 756.2.2 Consistency and longevity . 766.2.3 Build on the momentum of NRAS . 776.2.4 Administration . 776.2.5 Cross-subsidisation. 776.2.6 Delivering a variety of products . 776.2.7 Social infrastructure . 786.2.8 Long-term affordability . 786.377.1Lessons from international schemes: a view from the US and UK . 796.3.1 Understanding the key differences between countries . 796.3.2 Key messages . 80POLICY IMPLICATIONS . 83Summary of NRAS outcomes . 83v

7.2Key recommendations . 837.2.1 Scheme design . 847.2.2 Finance and funding . 867.2.3 Capacity building. 867.2.4 Summary . 86REFERENCES . 88APPENDIX . 98vi

LIST OF TABLESTable 1: Agreement types under the Rental Accommodation Scheme . 21Table 2: NRAS incentive amounts and contributors (2008–15) . 23Table 3: Summary of quarterly progress . 28Table 4: Incentive status by state/territory . 29Table 5: Dwelling type by incentive status (June 2015) . 29Table 6: Number of total incentives by state and geographic distribution . 31Table 7: Socio-economic indicators. 33Table 8: Investment potential indicators . 33Table 9: Examples of the composite measures in practice . 34Table 10: Characteristics of typical suburbs—socio-economic composite measure . 35Table 11: Characteristics of typical suburbs—investment potential composite measure. 36Table 12: Distribution of incentives . 37Table 13: Comparison of socio-economic measure across four capital cities . 42Table 14: Comparison of the investment potential measure across four capital cities 43Table 15: Comparison of the socio-economic measure by state. 44Table 16: Comparison of the investment potential measure by state . 44Table 17: NRAS impact on existing suburbs . 47Table 18: The proportion of Sydney metropolitan region suburbs in which householdswith eligible NRAS incomes can rent an affordable house . 48Table 19: Proportion of suburbs in metropolitan regions which become accessible toeligible households under NRAS . 48Table 20: Impact of NRAS on mean housing cost burdens for NRAS eligiblehouseholds (2011) . 51Table 21: Impact of NRAS on housing stress for NRAS eligible households (2011) . 52Table 22: Distribution of NRAS eligible households residing in and outside of NRASareas by remoteness area (2011) . 53Table 23: Distribution of NRAS eligible households residing in and outside NRASareas by SEIFA decile (2011) . 54Table 24: Housing expenditure profiles of NRAS eligible households residing in andoutside NRAS areas (2011) . 55Table 25: Impact of NRAS on the housing affordability positions of NRAS eligiblehouseholds residing in and outside NRAS areas (2011) . 55Table 26: Annual tax expenditure on the LIHTC program . 59Table 27: Affordable Housing Programme average gross rents as a proportion ofmarket rent (including service charges) by HCA Operating Area (end ofSeptember 2014) . 66Table 28: Affordable Rent units by region (2014)1 . 68vii

Table A1: Details of French taxation policies to increase the supply of rental dwellingsfor the intermediary sector and middle-income families . 98Table A2: 2014–15 household income eligibility limits . 99Table A3: Incentive distribution . 99Table A4: NRAS selection criteria . 100Table A5: State and territory affordable housing priorities for NRAS . 102Table A6: Profile of dwelling types by state/territory (%) . 103Table A7: Profile of dwelling size by state/territory (%) . 103Table A8: Affordable Rent units by size . 103Table A9: Comparison of supply mechanisms. 104Table A10: Comparison of affordability measures . 105viii

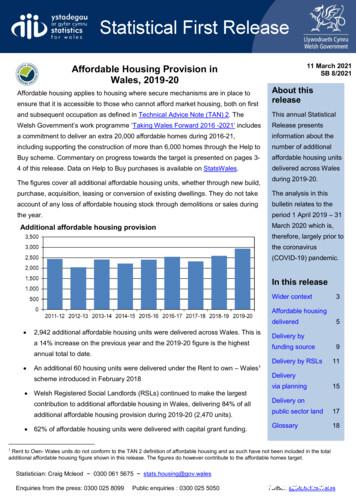

LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1: Subsidised affordable rental housing: actors and outcomes . 8Figure 2: Spatial distribution of NRAS incentives in Sydney . 38Figure 3: Spatial distribution of NRAS incentives in Melbourne . 39Figure 4: Spatial distribution of NRAS incentives in Brisbane . 40Figure 5: Spatial distribution of NRAS incentives in Perth . 41Figure 6: Additional affordable homes* provided by type of scheme, England. 66Figure 7: Affordable Rents housing stock as a proportion of social rental housing stock(all sizes). 69ix

ACRONYMSABSAustralian Bureau of StatisticsAHGPAffordable Homes Guarantees Programme (UK)AHPAffordable Homes Programme (UK)AHURIAustralian Housing and Urban Research InstituteAIHWAustralian Institute of Health and WelfareAMIArea Median Income (US)ANAOAustralian National Audit OfficeANUAustralian National UniversityARIAAccessibility/Remoteness Index of AustraliaCHPCommunity housing providerCRACommonwealth Rent Assistance (Australia)CRinvACommunity Reinvestment Act (US)DCLGDepartment for Communities and Local Government (UK)DECLGDepartment of Environment Community and Local Government(Ireland)DHSDepartment of Human Services (Australia)DSSDepartment of Social Services (Australia)ECUEdith Cowan UniversityFaHCSIADepartment of Families, Housing, Community Services andIndigenous AffairsGFCGlobal Financial CrisisGLAGreater London AuthorityHCAHomes and Communities Agency (UK)HILDAHousehold, Income and Labour Dynamics in AustraliaHOMEHOME Investment Partnerships Program (US)HUDDepartment of Housing and Urban Development (US)IAHInvestment in Affordable Housing (Canada)IRRInternal rates of returnIRSDepartment of Treasury’s Internal Revenue Service (US)IRSDIndex of Relative Socio-Economic DisadvantageLIHTCLow-Income Housing Tax Credit (US)NAHPNational Affordable Housing Programme (UK)NCSHANational Council of State Housing Agencies (US)NHSCNational Housing Supply Council (Australia)NRASNational Rental Affordability Scheme (Australia)x

NSWNew South WalesNTNorthern TerritoryOCPDOneCPD Resource Exchange (US)QCTQualified Census Tract (US)RASRental Accommodation Scheme (Ireland)SASouth AustraliaS106Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (UK)SEIFASocio-Economic Indexes for Areas (Australia)SERCSenate Economics References Committee (Australia)SOMIHState owned and managed Indigenous housingUWAUniversity of Western AustraliaWAWestern Australiaxi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYA supply of affordable rental housing is essential to allow households to transition outof scarce public and social housing and into the private rental sector. Affordable rentaloptions are essential for those households already in the private rental sector who arestruggling to pay market rents. This report explores the lessons that can be learntfrom the National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS) (discontinued in 2014), whichsought to stimulate the supply of affordable rental housing for low- and moderateincome earners. Drawing on evidence from comparable international programs forsubsidising rental housing supply, the report makes recommendations on how todesign and fund a new scheme to deliver the supply of affordable rental housingrequired in Australia.Key findings By June 2015, NRAS had delivered 27,603 dwellings with a further 9,980 to bedelivered, 76 per cent of which were in major cities. Dwellings were deliveredacross a variety of housing types including apartments (39%), separate houses(22%), studios (17%) and town houses (22%). The variety of dwellings deliveredwas a very positive outcome. Dwellingswere delivered in suburbs with a range of socio-economiccharacteristics and with generally good-quality transport infrastructure. Theallocation decisions were a combination of financially feasible project applicationsand state government directed housing priorities, and the approach worked well indelivering quality spatial outcomes. Subsidising rents to 20 per cent below market levels, the model adopted by NRASnot only increases the number of suburbs accessible to income-eligiblehouseholds but, if such a discount were available to all eligible households, wouldlift a third of them out of housing stress. NRAS was discontinued in May 2014 after almost six years. Although not withoutproblems, this research identified NRAS as an effective supply stimulus, deliveringtens of thousands of units in a relatively short timeframe. Concerns about complexadministration, poor targeting and administrative delays resulted in thediscontinuation of the scheme just when momentum and private-sector investorconfidence was building. Strengths of the scheme included: the ability to combine subsidies from a varietyof sources; the level of engagement from the community housing sector and fromprivate investors, particularly in the later rounds; the variety of dwelling types andsizes delivered; and the level of innovation it generated within the industry. Theweaknesses were its administration and lack of longevity. A new program to deliver a supply of subsidised affordable rental housing shouldbe introduced as soon as possible to build on the investment momentumgenerated by NRAS, which saw the final three funding rounds (i.e. calls forapplications) heavily oversubscribed and a secondary market for incentivesstarting to develop. A new program needs clear and measurable targets and objectives, and mustdemonstrate long-term commitment of government to secure the confidence of theinvestment sector. It should run alongside alternative affordable housinginvestment options, such as a financial intermediary designed to secure low-costfunding for the community housing sector.1

A subsidised affordable rental scheme, combined with planning mechanisms todeliver land for affordable housing and measures to build the capacity of thecommunity housing sector, could deliver a significant supply of dwellings to helptenants transition from social housing into the private rental market.BackgroundThe introduction of the NRAS in 2008 represented a significant shift in the provision ofhousing assistance in Australia, for the first time leveraging private investment in thesupply of affordable rental housing at a national scale. In the context of decliningrental and home-purchase affordability in Australia, and sluggish rates of new housingconstruction, NRAS addressed important goals for boosting the supply of totaldwellings, not just affordable dwellings. In contrast to traditional approaches to socialhousing, NRAS represented a mixed market approach, able to integrate affordablerental accommodation within wider market developments. This report exploreslessons that can be learnt from the operation of NRAS. Supplemented by lessonsfrom comparable international schemes, including detailed case studies of the UnitedStates (US) and England, this report generates a set of guidelines for the delivery ofany future subsidised private rental housing scheme within a broader affordablehousing investment framework.Research methodThis project addressed the following research questions.1. How have other countries with similar housing systems delivered subsidisedaffordable rental housing and what lessons can be learnt from the outcomes?2. To what extent has NRAS been effective in delivering a supply of housing acrossAustralia to address affordability in areas with differing dwelling price/rent anddemographic characteristics?3. To what extent has NRAS affected the supply and affordability of dwellings at thelower end of the private rental market?4. Is there potential for an alternative model to deliver subsidised affordable rentalhousing supply?The methodology focused on the outcomes, actors and institutions engaged inhousing delivery. Policy documents from Australia, the US, England, France, Canadaand Ireland informed an assessment of policy mechanisms employed in thosejurisdictions, with international experts providing detailed case studies on the US andEngland.Affordability and spatial outcomes for NRAS were analysed with reference to suburblevel data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), rent/price data from RPData,and NRAS output data derived from the NRAS Quarterly Performance Reportspublished by the Department of Social Services (DSS). These data were mappedusing ArcGIS. Affordability outcomes were computed with reference to data from thesurvey of Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA), allowing anassessment of the extent to which subsidised rental housing impacts on housingaffordability and on households’ rental affordability stress.An Investigative Panel, held in September 2015, considered the potential for a newscheme to deliver subsidised affordable rental housing. The Investigative Panelincluded: CEOs from community housing organisations in Queensland, SouthAustralia (SA) and Victoria; a manager from a major financial institution; an affordablehousing consultant; the CEOs of two affordable housing development companies; anda number of leading academics. Additional evidence for the project was gathered2

through interviews with representatives from state government, community housingproviders, the development industry and the valuation profession.FindingsBy June 2015, NRAS had delivered 27,603 dwellings with a further 9,980 to follow. Ofthese, 75.7 per cent were in major cities, with smaller proportions in inner regional(13.9%), outer regional (8.7%), remote (1.4%) and very remote areas (0.4%). Avariety of dwelling types were delivered, including apartments (38.7%), separatehouses (21.9%), studios (17.2%) and town houses (22%). The variety of dwellingsproduced was a very positive outcome, in contrast with patterns of delivery from someinternational schemes, such as the American Low-Income Housing Tax Credit(LIHTC) scheme, which provides volume but has delivered mainly apartments withininner city areas.Queensland had the greatest proportion of NRAS dwellings at 27.7 per cent, followedby New South Wales (NSW) (18.2%), Victoria (16.3%) and Western Australia (WA)(13.9%). For this reason, the analysis of spatial and affordability outcomes from NRASfocused on these four states. The study developed a composite measure to identifypatterns of outcomes related to socio-economic characteristics and investmentpotential. NRAS dwellings were delivered in suburbs with a range of socio-economiccharacteristics, although not at the very top and bottom of the scale. Most of theNRAS units were supplied in locations served by good-quality transport infrastructure.The distribution of NRAS incentives across states/territories and regions was found tobe a function of two drivers: firstly, the priorities of both the federal and stategovernments; and secondly, the financial viability of a project as determined by theapproved participants (developers/investors). The dwellings delivered were clusteredin suburbs with certain investment characteristics, which ensured the incentivedelivered value to the investor, be that the community housing sector or a privateinvestor. For example, for a weekly market rent of 300 per week, the 20 per centreduction reduces rental income by 3,120 per year, meaning that the incentive ofaround 10,000 still delivers a considerable gain to the investor. With a rent of 600,the annual reduction is 6,240 and the gain is much smaller. Ignoring the after-taxposition, the higher the market rent, the less beneficial the NRAS incentive. Tomaximise the impact of the incentive, private-sector investors sought areas withpotential for capital growth combined with a rent that was low enough to benefit fromthe incentive itself.Subsidising rents to 20 per cent below market levels increases the number of suburbsaccessible to income-eligible households. For example, in Sydney, 62 suburbs wereidentified as having 15 or more total incentives (NRAS dwellings). A household of twoadults or a sole parent with one child on an eligible income could afford to rent in only10 per cent of these suburb

Title Subsidised affordable rental housing: lessons from Australia and overseas ISBN 978-1-925334-29-6 Format PDF Key words subsidised affordable rental housing, housing affordability, institutional investment Editor Anne Badenhorst AHURI National Office Publisher Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited Melbourne, Australia

UNDERSTANDING AFFORDABLE RENTAL HOUSING SUMMARY Housing is a basic human need. Where one lives is a key determinant of one's quality of life, impacting health outcomes, employment, educational opportunities, and social connections. Yet millions of poor Americans lack safe, decent rental housing that is affordable to them and are

THE NEED FOR MORE AFFORDABLE rental housing is on the rise, but so are the costs to develop that housing. In September 2012, Enterprise Community Partners and the Urban Land Institute's Terwilliger Center for Housing launched a joint research effort to examine the various factors affecting the cost of developing affordable rental housing.

additional affordable housing provision during 2019-20 (2,470 units). 62% of affordable housing units were delivered with capital grant funding. 1 Rent to Own- Wales units do not conform to the TAN 2 definition of affordable housing and as such have not been included in the total additional affordable housing figure shown in this release.

3. Develop criteria or definitions of affordable housing. 4. Reduce the impact of regulations on affordable housing. 5. Contribute land to affordable housing. 6. Provide financial assistance. 7. Reduce, defer, off-set, or waive development fees for affordable housing. 8. Establish a land banking program to ensure the availability of land for future

Mercy Housing Sue Reynolds— . Affordable housing developers compete to creatively stretch and utilize a limited pool of public and private financing sources to develop housing. And even though the demand for affordable housing continues to far outstrip our ability to supply housing, the affordable housing industry has changed .

address the State’s affordable rental housing and juvenile justice needs. Proposed Project 2. The Project involves the redevelopment of an underutilized State-owned property into a mixed-use development consisting of affordable rental housing, a Judiciary services center/shelter, and parking. Site 3. The State-owned Property consists of .

RENTAL PROPERTIES 2015 ato.gov.au 3 Rental properties 2015 will help you, as an owner of rental property in Australia, determine: n which rental income is assessable for tax purposes n see which expenses are allowable deductions n which records you need to keep n what you need to know when you sell your rental property. Many, but not all, of the expenses associated with rental

tulang dan untuk menilai efektivitas hasil pengobatan. Hasil pemeriksaan osteocalcin cukup akurat dan stabil dalam menilai proses pembentukan tulang. Metode pemeriksaan osteocalcin adalah enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Nilai normalnya adalah: 10,1 9,4 ng/ml.8 Setelah disintesis, OC dilepaskan ke sirkulasi dan memiliki waktu paruh pendek hanya 5 menit setelah itu dibersihkan oleh .