Interior Design - Hkida

Lead SponsorINTERIORDESIGNBODY OFKNOWLEDGEBook 2INTERIOR DESIGNTHINKINGJOINTLY RESEARCHED AND PUBLISHEDby Hong Kong Interior Design Association & The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

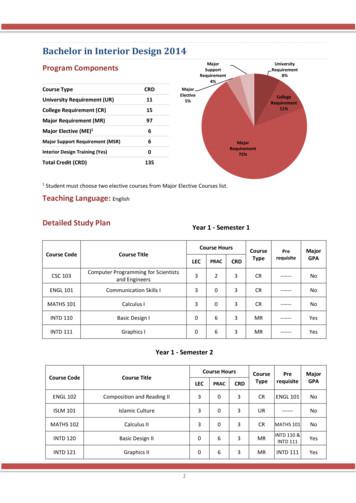

ContentsPrefaceiChapter 1Qualities and Main skills of an Interior Designer1Chapter 2History and Interior Design – The Orient and the Occident.5Chapter 3Interior Design Education21Chapter 4Part 1 Interior Design Education—2-year Higher Diploma program23Chapter 5Part 1 Part 2 Interior Design Education—4-year Bachelor’s Degreeprogram32End NoteAbout the Authors

PREFACEAt present, there are no formal educational materials for Hong Kong interior designlearning, and educators can only rely on ad hoc literature produced overseas (particularlyin the West), or architectural-based materials to learn about interior design. Given thatinterior design has already established a unique and well-defined body of professionalknowledge, and is firmly rooted in the cultural and social practices of a place, thereis a need for interior design textbooks to reflect this context and allow interior designstudents to keep pace with rapid development of the industry.This series of interiordesign textbooks is aimed at satisfying the needs of Hong Kong interior design studentsat different academic levels from diploma, higher diploma to bachelor’s degree. Filledwith case studies of award winning works from across the Asia-Pacific region andbeyond,as well as interviews and articles written by well-known professionals andacademics from Hong Kong and around the world, these are the first interior designtextbooks researched and written in Asia.The series contains six books, related to the 6 body of knowledge areas well-defined inthe Interior Design Professional Guideline, published by the Hong Kong Interior DesignAssociation (HKIDA) in 2014. Based on research of reputable international standardsand confirmed by surveys of local interior design educators and practitioners, thisguideline sets out in a systematic way the knowledge and skills that Hong Konginterior designers should possess. The 6 body of knowledge areas covers and followsthe typical process of any interior design project, which includes: Human Environment Needs Design Products and Materials Communication Interior Construction, Codes and Regulations Professional PracticeBook 2 focuses on the required knowledge related to Interior Design Thinking: topicsinclude the Definition of Interior Designer’s Qualities & Values, Interior Design History &Development in Western Countries and South China Region, Pedagogical Approachesof Interior Design Education in Sub-Degree and Degree Levels in Hong Kong (Part 1 &Part 2 levels defined by HKIDA).Our greatest challenge in compiling this book series was deciding which keycontent to select from the vast pool that is relevant to not only global but also localcontext and become useful teaching resources & materials for educators’ futureelaboration. For this reason, choosing examples to fit within the physical constraintsof a book required a rigorous edit. We hope it will be of enormous benefit tointerior design students, educators and practitioners and inspire everyone to lookfor more.Horace PanProject Chief Investigatori

CHAPTER 1Qualities and Main Skills of an Interior Designerby Manfred YuenThose who choose design as a profession likelywish to innovate, to think, to create and tomake changes to the world and the way theylive. The life of a designer is interesting becausethe act of designing has multiple embodiments:the job of designers is to identify questions andcreatively seek solutions. Questioning, therefore,is the core of a designer’s work.“If the sun rises from the east every morning,how should I design a shading device so that itmay prevent the sun’s glare from waking me upin the morning?” Simple questions are the mostdifficult to answer. To answer this question, firstlyone must know where east is vis-à-vis my currentlocation, and then design a device that wouldshade me from the morning sun.Fig. 1.1 Étienne-Louis Boullée plan for the National Library,1785.Design is a plan, and subsequently, a result ofa plan that would be executed in answer to araised problem. Thus, the design is merelya plan to be executed. This is a central notionof design education because, within the abovedefinition of design, both the identification of thequestion and the product/answer of the questionare equally important. Some great designersmay successfully raise questions but notprovide succinct answers. The 18th centuryarchitect Étienne-Louis Boullée or LebbeusWoods (May 31, 1940 – October 30, 2012) builtvery few buildings, but their influences on thedesign world still echo. Asking good questions aswell as providing good solutions to the questionsthat you have raised is, in essence, the corevalue of design education.1The realization and implementation of the designare of as much importance as the design visions.Designers need to be equipped with the skillsand know-how to realize and implement theirdesign. These are no easy tasks; they involvethe art and instruction of crafting. Providingaccurate instruction to artisans who may be moreexperienced than you on the implementationof the design is a skill in itself, and perfectingit can take a lifetime.A designer must be able to communicate;visual communication means such asperspective drawings and walkthrough videosare the most commonly accepted forms ofrepresentation means for interior designers; it isour job to represent the vision of our design toclients, users and stakeholders.The education of design is never easy becauseapart from the pragmatic embodiments, greatdesigns seek resonances with users and thepublic and touch their hearts; skilful designersraise good questions, realize and implementdesigns with impeccable craftsmanship, and areable to communicate their visions and valueswith people, but at the end of the day, designshould also be personal and possess a personaltouch that is endeared to its creator.

Why does interior space need to be designed?Interior Design TrainingWhy does interior space need to be designed?The reasons may lie within a spectrum wherepragmatism and subjectivity are on oppositeends.With proper training, anyone can be an interiordesigner. Interior designers, however, arecommonly particularly sensitive towards theergonomics of the human body, abstractions(narratives and similes), lighting, materiality, andproportions. Organization values (the most pragmaticreason)Psychological valuesGeneral aesthetic valuesPersonal preferences (the most subjectivereason) Organizational valuesThis refers to the act of dividing larger internalspaces into smaller spaces and/or to furnish thespace according to its functional and ergonomicneeds. This is the beginning of interior design.Psychological valuesOnce the functional need of the space is fulfilled,the spatial quality of interior spaces needs to becatered for because they would affect the wellbeing of the users psychologically. For example,low partitions that engulf library desks allowthe reader to have more privacy; a darkerroom will encourage its inhabitant to fall asleep,while a restaurant styled with Art Nouveaudecoration may evoke nostalgia, etc.General aesthetic valuesJudging aesthetic merits can be a subjectiveprocess, but there are commonly acceptednorms which may define a quality space. Forexample, a room which offers a sea view isgenerally popular even though the personalpreferences for individuals may vary. Thus, itis important that designers learn about thesenorms through our learning and practical workexperiences so that their design may relate tothese norms.Personal preferencesEveryone has different opinions about theirneeds and wishes. For instance, some peopleprefer a smaller bedroom rather than a largerone because it gave them a sense of warmth,and so personal preferences can sometimescontradict general aesthetic values.2“Style” and “taste” are not prerequisites of beingan interior designer; rather, one’s “taste” and“style” will develop through time along with thematurity of one’s career.Interior designers should be equipped with thefollowing skills and knowledge in their training: Spatial planning skills;Project managing skills: interior designersare time and budget conscious;Understanding of construction: the sequenceand the logistics of the assembly of materials;Communication skills, both verbally andgraphically;Knowledge about the world around y, etc.;Problem solving skills.Good interior designers, no matter if they areyoung or old, are full of curiosity. They willconduct research on issues before engaging aproject, and they like dealing with people, to learnand empathize with others’ needs. Finally, theyare open to new ideas; they like technologiesand the knowledge of new materials.

Personal SpecificationIn conclusion, the personal qualities and skills that interior designers should possess can be summarizedaccording to the following table.INTERIOR DESIGNER: PERSONAL SPECIFICATIONMotivation and CommitmentTo have the desire to change, restoreand improve the environment. To be a visionary in pursuing dreams ofself-fulfilment as well as satisfying theclient. To have good management skills. To realise powers of expression andmeaning in one’s work.Organisation Abilities To be able to handle a vast range of materials, products andservices, as well as being resourceful in finding them. To be able to organise and store information for reference andfor applied use when necessary. To be a team player – with other colleagues as well as withconsultants. To be able to work to a programme and meet deadlines.Holistic ApproachTo be sensitive and perceptive aboutpeople’s needs and to ask the rightquestions. To maintain a creative driving force. To make strong value judgementsconcerning quality and costs andmeeting the budget. To have good verbal and writtencommunication skills and clarity ofintent.Hands-on Skills To have good analytical and problem-solving skills. To becompetent in handling three-dimensional forms, spaces,colours and textures. To have a feeling for materials and be able to put thingstogether in construction. To be proficient in drafting by hand and using computer-aideddesign (CAD). To be able to sketch and draw to facilitate one’s own designprocess from conception to completion, and to aidcommunication and the presentation of ideas. To be competent with latest technological/ graphic aids thatassist with the design process and presentation).To have good analytical and problem-solving skills. 3

CHAPTER 2History and Interior Design – The Orient and the Occident.by Dr.ir. Gerhard Bruyns and Dr. Tung Kwok-wah, HenriHistory and DesignHistory is part and parcel to the discipline of design. History of design or the history of theenvironment remains central to foundational knowledge of any design discipline, interior orexterior in nature. In a broad sweep, the position of history has over years and decades changedfrom, on the one hand, being a mirror of the past, whilst on the other, an instrument to formulatefuture tendencies and a source from which designers draw inspiration.To understand the history of interior design, one should understand the history of its context, orin other words, the history of the city. The city provides a context by which one can understand howsocial and technological factors influence interior styles. The interior is as much part of the cityas the city is to the interior. Everything that the city produces, documents or designs, is eithermade within, or is drawn into the lived interior. Interior and exterior is therefore indisputably fused intoa coherent whole.In the beginning, human settlements consisted of singular one or two room dwellings, fenced in forprotection. Interiors in this sense were multi-functional spaces, serving several uses at any given time.Gradually, single houses became collections of dwellings, generating the first cohesive settlements,villages, towns and, in time, fully fledged cities that we recognize today. In a similar light, the interior’sdevelopment was from a sparse space, minimal in nature, to intricate spaces molded from volumes,sculpture and geometries, off-set with specific effects of light and mirroring. In its present format,interiors have returned to either a minimalist setting or as spaces that have become obsessed withexcess and opulence.Architecture and interior design developed in tandem in the East and West, evolving accordingto the changing needs and prevailing cultural influences. The chart below offers a comparativeperspective on the development in cultural, architectural and design in both the Orient (East) aswell as the Occident (West). Contextually aligning the history of the interior to both European andAsian narratives offers a parallel understanding of history that allows for cross referencing mutualconditions within the historical streams. Global events may cause certain transformations tooccur in design, but the actual response within both cultures may differ in significant ways.The overview provided here, however brief, steers clear from stylistic emphasis of one style overanother. Each stream is to be read in relation to design development occurring in three distinct periods;the pre-industrial (1500 -1800), industrial (1800 -1900) and post-industrial period (1900- present).4

nacularLingnan/CantonAntient Greece:(900 – 30 BCE)East – Chinese wooden frame construction (more than 4000 years ago)A cultural style expressed inpainting, art and architecturethat has had fundamentalimpact on Western culturesand their approach to the builtand decorative arts.Common Chinese wooden framesystems include the post and lintelconstruction (抬梁式木結構), whichwas more popular in North China, andthe column and tie construction (穿斗式木結構), which was a more vernacularpractice in South China. The latter wassimilar to Tudor Revival style in terms ofmaterial and structure.The mainstream wooden frameconstruction involved a relatively fixedset of architectural vocabularies andgrammars (especially in the case of thepost and lintel construction) for a verylong time. It thus contributed to similar/coherent built circumstances (bothinteriors and exteriors), which wererare in other civilisations.1 Due to itspermanence and prevalence, the woodstructural system became a prominentrepresentation/icon of Chinese culture.Spatial layout:Spatial layout:The geometric periods gaverose to the canonical typologiesof the Greek temple, withdouble portico’s and central‘Cella/Naos’ surrounded by aseries of single row columns.Stylistically Greek spatiallayouts followed the Egyptianpost and lintel method ofconstruction.Building complexes are characterizedby groups of individual buildingsconnected by courtyards, coveredwalkways and porches, resulting in richlayers and transitions of interior spaces.The corresponding spatial hierarchyis socially and politically significantas it reflects the house owner’s familystructure and social status.Architectonic:Architectonic:Most noticeable is thedevelopment of theandIonic orders of construction,with the later addition of theCorinthian Order.The wooden frame construction givesthe freedom in walling and fenestration,which is comparable to Le Corbusier’sDom-ino system (1914). By adjustingthe proportion between walls andopenings, the wooden system canadapt to different climates.25Fig. 2.1 The drawing of large woodproduction, no. 1 7Fig.2.2 Drawingproduction, no. 26oflargewoodSource: Liang, Yingzaofashizhushi(營造法式註釋), 265.

Aesthetics:Aesthetics:Interior detailing is richly detailedin full colour palette, off-set withthe use of translucent marbleroofs and prominent buildings.The post and lintel construction waswell documented in Yingzao Fashi“The State Building Standards” ofthe Song dynasty (1103). Knownas the official pattern book, it is asystematic document characterizedby rules and formulae basedon a modular system (i.e., theCai system) for determining thepositions and modellings (e.g.,dimensions, shapes, forms anddetails) of wooden elements, whichessentially express the uniqueaesthetics of Chinese buildings.For example, the rule of juzhedetermines the elegant curvy andup lifting shape of the Chinese roof(which is the quintessential symbolof Chinese culture).ROMAN PERIOD: (753 BC –337 CE).Spatial Layout:Taking precedence from the Greekbuilding orders, the Roman addedto the spatial oeuvres with thedevelopment of Roman Concrete.The construction of vaults andarches typified Roman technologyand the construction of Barrel(Tunnel) Vaults, Groin (Cross)Vaults and Hemispherical Domes.In addition, the possibilities offenestration and clearstory windowsimproved light qualities, withfriezes, wall murals and sculpturaldevelopment influencing both thecivic and domestic interiors.Civic buildings such as forumsand public baths became largerin scale, forming complex spatialarrangements.Domestic interiors followed thecourtyard or atrium layout withperipheral spaces arranged aroundcentral yards and water features.6Fig.2.3 - Chinese column orders 8Fig 2.4 & 2.5 Chinese DougongColumn detail. 9 10The bracket system/dougong,which is a complexification of theChinese corbel invented more than2,000 years ago, also deservesattention for its aesthetic quality:The dougong was originallyconceived as a structural element,but its decorative potentiality wassoon discovered and exploited tothe utmost degree. 3Functionally, the bracket systemacts as a cantilever system for theroof eave. Aesthetically, it borrowsthe natural form of a flower toexpress the pleasant visual effectof ‘a flower coming into bloom’, 4which is comparable to the visualeffect of Greek/Roman capitals. Allin all, the bracket system involvesa significant synthesis of functionaland aesthetic considerations. 5 Itsmodelling relates to an appropriatecomposition of well-formed parts,exemplifying the fact that thearchitectural and interior design isessentially “an art of theensemble”.6Fig 2.6 Greek classical orders, Ioniccolumn analysis 11Fig 2.7 & 2.8 Doric and Ionic columnfooting, Athens, Greece. 12Fig 2.9 Typical Greek peripteraltemple plan. 13

Aesthetics:Although dimly lit in some instances,rooms have sufficient ventilation.Geometricproportioningisemphasized within the paneling anddecorative aspects of the interior,in rich colour usage and detailing.Apart from the panels and muralsdepicting nature, sculptures andrelief friezes added to the aestheticquality of spaces.Period of importance following theRoman period include:Early Byzantine Period(324–726),Middle Byzantine Period(843–1204),Late Byzantine Period(1261-1453),Fig 2.10 Elemental analysis, Gothicchurch interior. 14Early Medieval Period(1261-1453),Romanesque Period(1000 -1200),Gothic Period(1140 – 1500),Later Medieval Period(1200-1400),The Renaissance Periods(1385–1500),The Baroque Period(1600 – 1700),Rococo &Neo Classical Periods(1700 – 1800),7Fig 2.11 Groin vault, Gothic interior,Spain. 15

ation in Architecture,modernism’s stylistic toneexiledexcessivenessininterior and architecturaldesign. With the mass scaleproduction of steel, concreteand the further developmentof reinforced concrete, theideals were to strip buildingsbare to their essence andmaterial ‘nakedness’.West East (juxtaposition) Chinese Renaissance style:ThemodernizationofChinesearchitecture was first conducted inNorth China against the politicalbackground of attempting to strengthenChina’s national power throughWesternization after the Opium Wars.Chinese craftsmen and builders, whenexposed to modern knowledge fromthe West via different channels, beganto speculate that Chinese architecturalpractice ‘might benefit from technicaland engineering innovations madeAdolf Loos’ essay “Ornament beyond China’s borders’. 17and Crime” (1908) formulatedthestylisticminimalism Since then, mergers between Chinesemantra for spatial design. and Western building techniques/Working across the decorative elements of different extents had beenand spatial arts, the minimalist attempted. The key issue was howagenda advocated an honesty the Chinese identity can be retainedof materials, primary colours during this process. This resulted in theand a return to the platonic Chinese Renaissance style in the firstshapes.half of the 20th century.In an urban sense, thespatial grid delivered auniversal design instrument.As developmental tendency,especially in the USA, thegrid become a unifying factoracross space and time. In duecourse, what was meant to actas unifying elements resultedin the functional separation ofurban functions, architecturesand spaces.8According to its methodologies andfeatures, the Chinese Renaissancestyle can be subdivided into twocategories: the adaptive approach ofconcrete construction and the stylisticadaptive approach (or revivalist style).Fig.2.12a & 2.12b Adaptive approachusing concrete construction: TenThousand Buddhas Hall of Miu FatBuddhist Monastery, Tuen Mun, HongKong.

Spatial layout:With functionality being the drivingforce, spatial and interior designsaw a simplification based oneither Loos’ spatial (Raum) planor on Le Corbusier’s Free plan.The spatial plan opened all spatiallayout to focus on the interior,with limited fenestration withinthe perimeter walls. The free planopened all aspects of the design,layout, structure, fenestration andfunctional arrangements. Principlesof the free plan was later formalizedby Le Corbusier in his treaty ofArchitecture under the 5 points ofArchitecture: pilotis, free groundplan, free façade, horizontalwindows and roof garden principles.The adaptive approach of concrete construction:This approach mainly involved therealization of the spatial layout andform of traditional Chinese woodenframe construction in Westernconcreteconstruction.Thisapproach is comparable to theBeaux-Arts’ attempt to integrateClassical styles with engineering.Key examples of the adaptiveapproach of concrete constructioninclude the campuses of YenchingUniversity in Beijing (1919)designed by Henry Murphy, andGinling College for Girls in Nanjing(1921) and Ten Thousand BuddhasHall of Miu Fat Buddhist Monasteryin Tuen Mun (1973).Architectonic:Architectonic and aesthetics:Influence of reinforced concreteopened architectonic expressionof buildings and spaces. Thereturn of platonic shapes andvolumes delivered cubic volumesin architectural sense, with interiorsbeing spare and open. Windowsbecame expressive features openingall perspectives into as well as outof the spatial forms. Furthermore,the ‘free’ plan brought a newsense of design freedom to space.Both the spatial and architectonicexpression of the free plan deliveredunsymmetrical layouts, emphasisedby the functional qualities of eachpart and its elemental arrangements:columns, ramps, staircases andbuilding edges.This approach may not be quitesuccessful because it wasconceptually inconsistent to usereinforced concrete on the outsetas concrete buildings were not“Chinese throughout” from astructural viewpoint. 18 Moreover,aesthetically the change ofmaterial and the correspondingcraftsmanship often lead tothe distortion of proportions,detailing, visual appearances andcompositions of building parts oftraditional Chinese wooden frameconstruction.9Fig. 2.13 Stylistic adaptive approach:Morrison Building of Hoh Fuk Tong,Tuen Mun, Hong KongFig 2.14 Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye,France, 1929. 30Fig 2.15 Frank Lloyd Wright, RobieHouse, 1907 - 1909. 26Fig. 2.16 Frank Lloyd Wright, RobieHouse Stain Glass Detail, 1907-1909.27

Aesthetics:With most buildings painted white,their characteristics were of lightfilled interiors, accent of colour andthe openness of flow of the interiorplan. Columns varied in scale butwere circular in preference andof reinforced concrete. A stronginfluence in the approach to the freeplan was the mechanistic approach(automobiles, airplanes, and shipliners) to design, giving expressionto all functional components of thespace.Bauhaus School:Founded by Architect Walter Gropiusin Weimar (1919),the BauhausSchool of thought reconceptualisethe all forms of art, architecture,graphic design, interior design,industrial design and typography.As one of the most influentialschools in Europe of the 20thCentury, Bauhaus’ ideas andconcepts was an off-set against theBeaux-Arts movement, free fromhistorical reference or precedent.Documented in its official manifesto,the school advocated strong basicdesign – which included strongprinciples of composition, thedevelopment and application ofcolour theory and two and threedimensional explorations.With the ‘simplification’ of design,new materials were explored, withthe infusion of disciplines with oneanother. Or rather “the coordinationof all creative efforts” 16, as forexample pottery, weaving, paintingand the design of space was seenas a “collective work of art inwhich no barriers exist between thestructural and the decorative arts”(ibid).(cf. Bauhaus Weimar 1919 – 1925,Bauhaus Dessau 1925 – 1932,Bauhaus Berlin 1932 – 1933)10The stylistic adaptive approach(Revivalist style):This approach is characterizedby a juxtaposition of a Westernstyle main body (e.g., the classicalrevival, classical eclecticism, ArtDeco, modern/ International Style)with a Chinese-style roof structure(which represents the Chineseidentity). This kind of compositionwas first introduced and practisedby forerunners including Westernmissionaries and educationalistsin the late 19th century, with theintention of expressing theirrespect for the Chinese culture.Key examples include the MainHall (1879) and Science Building(1923) of St. John’s University inShanghai). This approach wasthen practiced by foreign and localarchitects.Since the 1930s, the stylisticadaptive approach has beencontinued and modified particularlyby the Beaux-Arts design method(of the American Tradition)practiced by the Beaux-Arts trainedChinese graduates who studiedabroad. Significant examplesinclude the Yale-in-China campusin Changsha designed by Murphy(1914), the Friendship Hotel inBeijing designed by Zhang Bo(1954) and the Morrison Buildingof Hoh Fuk Tong in Tuen Mun(1936).Spatial layout:The Western-style main bodies ofbuildings constructed according tothe stylistic adaptive approach didnot necessary follow the interiorlayout of the traditional woodenframe construction.Fig 2.17 & 2.18 Walter Gropius,Bauhaus, Housing complex andbalcony detail, Dessau, 1925 -1926 28

Key buildings and interiorsrepresentativeofmodernisminclude: Robie House, Chicagodesigned by Frank Lloyd Wright(1907 – 1909), The Bauhaus,Dessau designed by Walter Gropius,(1925 – 1926), Villa Savoye, Poissysur-Seine designed by Le Corbusier(1929) and Schröder House, Utrechtdesigned by Gerrit Rietveld (1924).Other influential European schoolof thought of the period includes:Supermatism, Constructivism, theArt Deco Movement, Surrealismand De Stijl.Aesthetics:It seems as though most of thebuildings of this approach wear “aWestern suit and a Chineseskullcap”. 19 The two parts simplydo not match – the approach ‘hadnot succeeded in giving to thelower portions of the buildings asufficiently Chinese look to be inharmony with the strongly definedChinese character of the roofs’. 20Since then, many practitioners ofthis trend have gradually shiftedtheir design approach by adoptingthe modern style/InternationalStyle.Fig 2.19 & 2.20 Walter Gropius,Bauhaus, Curtain wall and window,Dessau, 1925 -1926.West/East(synthesis)-Vernacular Lingnan architectureFig 2.21 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus,Door handle detail, Dessau, 1925 1926. 29The geographic condition of SouthChina or Lingnan region (includingCanton and Guangxi provinces)gave birth to an ocean culture,which had an “open and inclusive”attitude toward overseas cultures.This resulted in the intended andactive syntheses of overseaselements, and hence a culturalprocess of “glocalization”, uponwhich the cultural identity of theLingnan region largely depended.This “glocalization” relates to“a complex interaction of global[Western] and local [Lingnanvernacular] elements”, leading toa cultural/architectural ‘hybridity’that “cannot be reduced to clearcut manifestations of a total‘sameness’ or ‘difference’” 21–neither mere East nor West.11Fig 2.23 Aligned arcade buildingson West Embankment Street, ChikanAncient Village, Kaiping 31

Western styles were commonlyappreciated in the region. Theimport of Western building andinterior elements were mainlycaused by trade and emigration:i) contact with Western (building)culture via the Ocean Silk Road; ii)building precedents in the region,e.g., the Western style buildingsof the Thirteen Hongs of Cantonbuilt for foreign traders in the1820s; iii) architectural knowledgebrought back by overseas Chineseworkers in the 20th century. Thesecontributed to the emergence of thevernacular Lingnan architecture,which was mainly designed andbuilt by the local people andbuilders.Vernacular Lingnan architecturewas characterized not by directcopying but innovative synthesesof various building elements,which were largely driven by theaesthetic sense of the locals. Thesyntheses involved distinctiveexecution of details, skilledcraftsmanship (such as moulding)and harmonious compositions ofelements by breaking establishedarchitectural rules. Its aestheticachievement is thus comparable tothat of the architectural eclecticismthat was adopted in the West fromthe late 19th century to the early 20thcentury. Moreover, its preferencefor plants, flowers, leaves and fruitsfor the pattern design adopted onthe interiors and exteriors is similarto the practice of the Arts & Craftsmovement.12Fig 2.24 Façade details of the arcadebuilding at 41 West EmbankmentStreet, Chikan Ancient Village, Kaiping32

Three typical examples of thevernacular Lingnan architectureare listed below.1. Arcade buildings (1920s1930s)Typolog

is a need for interior design textbooks to reflect this context and allow interior design students to keep pace with rapid development of the industry. This series of interior design textbooks is aimed at satisfying the needs of Hong Kong interior design students at different academic levels from diploma, higher diploma to bachelor's degree .

Interior Design I L1 Foundations of Design* L1 Interior Design II L2 Interior Design II LAB* L2L Interior Design III L3C Interior Design III LAB* L3L Interior Design Advanced Studies * AS *Complementary Courses S TATE S KILL S TANDARDS The state skill standards are designed to clearly state what the student should know and be able to do upon

What is Interior Design? Interior Design is a "unique blend of art and science. Interior decorating is the embellishment of interior finishes and the selection and arrangement of fabrics and furnishings" according to Beginnings of Interior Environment by Phyllis Sloan Allen, Lynn M. Jones and Miriam F. Stimpson. Interior designers are trained .

interior spaces, interior surfaces, furniture, and ornamentation. Course Code: INTD 216 Course Title: Color in Interior Use of color in interiors. Emphasis on color theory, psychology of color and its effects on moods. Application of color in interior environments with lighting conditions. Course Code: INTD 220 Course Title: Interior Design II

Figure 6: 3 sub-segments of interior design firm’s client. 17 Figure 7: Customer segment of interior design market 19 Figure 8: Logo of TIDA (Thailand Interior Designer association) 20 Figure 9: Design process 21 Figure 10: Schematic design 22 Figure 11: Interior turnkey scope of

Aug 27, 2006 · The Interior Design Manual (IDM) will provide VA staff participating in the development of interior design projects with an understanding of their roles, responsibilities and the appropriate procedures for creating a comprehensive Interior Design environment. All VA staff members taking part in interior design are expected to follow this manual

INTERIOR DESIGN & BUILD ISLE OF WIGHT joisleofwight@yahoo.com 07964829997 www.coastiow.co.uk COAST IOW LTD INTERIOR DESIGN & BUILD Curabitur leo. COAST IOW LTD INTERIOR DESIGN & BUILD . Coast IOW Ltd - Interior Design Portfolio Created Date: 6/8/2021 8:14:52 AM .

how they applied BIM in the interior design development. Taking full advantage of BIM from basic to detailed interior design Using BIM for interior design Ikeda Architecture www.ikeda-architecture.jp Established in : 2010 Representative: Yoichiro Ikeda Speciality: Shop design interior Head Office: Yokohama, Japan Software: ARCHICAD, BIMx

Precedence between members of the Army and members of foreign military services serving with the Army † 1–8, page 5 Chapter 2 Command Policies, page 6 Chain of command † 2–1, page 6 Open door policies † 2–2, page 6 Performance counseling † 2–3, page 6 Staff or technical channels † 2–4, page 6 Command of installations, activities , and units † 2–5, page 6 Specialty .