UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Ceremonies In The Hebrew .

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Ceremonies in the Hebrew Bible: Ideologies of Textual Authority in Joshua 8, 2 Kings 22-23, and Nehemiah 8 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Lisa Joann Cleath 2016

Copyright by Lisa Joann Cleath 2016

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading Ceremonies in the Hebrew Bible: Ideologies of Textual Authority in Joshua 8, 2 Kings 22-23, and Nehemiah 8 by Lisa Joann Cleath Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor William M. Schniedewind, Chair The covenant reading ceremonies in Joshua 8:30-35, 2 Kings 22-23, and Nehemiah 7:72b-8:18 betray a developing interplay between the people of Israel and the book of the law. These narratives are unique in the Hebrew Bible in presenting the oralization of a covenant document to a specific audience. Previous scholarship on these narratives has focused on reconstructing the source-critical history of each account and the historicity of the reported events. For the following study, Joshua 8:30-35 and 2 Kings 22-23 represent earlier pre-exilic and exilic traditions, while 2 Chronicles 34-35 and Nehemiah 8 illustrate later post-exilic perspectives. However, supplementing source-critical scholarship, narrative criticism is used to contribute a fresh view of the relationship that the narratives construct between the community of Israel and their authoritative text. This study analyzes the characterization of the people and the characterization of the book of the law, both within the broader context of ancient Near Eastern ii

loyalty oaths and within the immediate context of the corpus of the Hebrew Bible. The sensory descriptions of the book of the law especially highlight how the textual artifact connects the particularized community of each respective narrative to the covenantal past of the Israelite people, while effectually executing that connection through differing loci of authority. This literary analysis reveals that each reading ceremony narrative manipulates the material functions of the text and its locus of authority according to its own ideology. The historical trajectory presented by these narratives portrays the people of Israel as progressively more exclusive, while portraying the book of the law as increasingly more written and less oral. Joshua 8:30-35 and 2 Kings 22-23 demonstrate that during the exilic period, the book of the law could be authorized either as Mosaic tradition or as a prophetic word from God. By the postexilic period, authorization through Mosaic discourse became pervasive. 2 Chronicles 34-35 and Nehemiah 8 illustrate this well-documented post-exilic phenomenon. In these narratives, by providing continuity between a particularized community and the Mosaic covenant, the book of the law stakes a claim that the true people of Yahweh are limited to the covenant reading ceremony participants. iii

The dissertation of Lisa Joann Cleath is approved. Yona Sabar Ra’anan S. Boustan William M. Schniedewind, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2016 iv

Table of Contents Abstract of Dissertation ii-iii Acknowledgements viii-x Vita xi-xii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Ancient Near Eastern Backgrounds for Reading Ceremonies 19 Chapter Three: Joshua 8:30-35 and the Oral-Written Text 53 Chapter Four: 2 Kings 22-23 and the Prophetic Text 112 Chapter Five: Nehemiah 8 and the Mosaic Text 212 Chapter Six: Conclusion 288 Bibliography 293 v

Abbreviations AJSL American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature BEATAJ Beiträge zur Erforschung des Alten Testaments und des antiken Judentum Bib Biblica BibInt Biblical Interpretation BBR Bulletin for Biblical Research BASOR Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research CahRB Cahiers de la Revue Biblique CBQ Catholic Biblical Quarterly CBW Conversations with the Biblical World DSD Dead Sea Discoveries HUCA Hebrew Union College Annual Int Interpretation Iraq Iraq JBQ Jewish Bible Quarterly JSOJ Journal for the Study of Judaism JSOT Journal for the Study of the Old Testament JBL Journal of Biblical Literature JNSL Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages JAAR Journal of the American Academy of Religion JAOS Journal of the American Oriental Society JCSMS Journal of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies JRAI Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute LC Language & Communication vi

NEA Near Eastern Archaeology Numen Numen: International Review for the History of Religions OTS Old Testament Studies Or Orientalia P&P Past and Present: a Journal of Historical Studies PRSt Perspectives in Religious Studies SR Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses UF Ugarit-Forschungen VT Vetus Testamentum ZDPV Zeitschrift des deutschen Palästina-Vereins ZABR Zeitschrift für altorientalische und biblische Rechtsgeschichte ZAW Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft ZTK Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche vii

Acknowledgments This dissertation is the fulfillment of an interest that I have had since the advent of my doctoral studies eight years ago: ideologies of authoritative text in ancient Israel. Under the encouragement and direction of the faculty at UCLA, I have grown into this project through the rigorous linguistic, historical, and methodological training of our many reading courses, seminars, and research projects. My committee members in particular have been essential to this pursuit. I am especially grateful to my advisor, Professor William M. Schniedewind, for mentoring me through a challenging program. Through all of my years of study, I have been thankful to have such a professional, kind, and grounded advisor. It was your suggestion to look at Exodus 24 that led me to study reading ceremonies in the first place. Thank you for showing me a world where language is active and dynamic. I also could not have completed this dissertation without the instruction and support of Professor Ra’anan Boustan, who over the years has challenged me with inspiring scholarship, endured many iterations of my once-nebulous project, and provided words of encouragement for the graduate student life. I will always be thankful to Professor Yona Sabar for bringing the language of Aramaic to life for me, offering humor through hours of text reading, and ultimately preparing me to work professionally in the exciting world of ancient texts. Finally, a sincere thank you to Jacco Dieleman, for facilitating a connection for me to the Berlin Museum and a wonderful opportunity to work directly with the Aramaic papyri of Elephantine. My dear colleagues at UCLA have been my life support and joy throughout our years together. Melissa Ramos, I have always valued your smart wit and focused work ethic. Thank you for showing me what it is to take your work seriously while not taking yourself too seriously. I don’t think I could have made it through those first overwhelming years of doctoral study viii

without the camaraderie you, I, and Andrew Compton formed. Alice Mandell, you have become a sister to me. Thank you for showing boundless generosity, humor, and strength in the midst of all the grit and grime that is the daily work of scholarship. Your loyalty and friendship have lifted me up constantly through our years of study. Here’s to a sisterhood based on wandering in the wild, good old silliness, and – ever more – good food. Jody Washburn, I would not have finished my dissertation without your partnership in the last year. You motivated me to set realistic goals and helped me feel brave enough to share my work with colleagues. Until we started working together, I didn’t realize that I needed the support that a writing partner could provide. Thanks for always listening to my fears and frustrations, encouraging me, and planning beautiful parties to brighten the way through. I owe a special thanks to those who came ahead of me at UCLA, especially Roger Nam and Jeremy Smoak. Roger, thank you for drawing me to UCLA with your enthusiasm for the collegiality and academic rigor of the NELC department, and for always taking me under your wing to share your professional wisdom, sense of humor, and love of food. Jeremy, I will always appreciate how you have modeled good teaching, shared resources without hesitation, and demonstrated a balanced perspective towards the academic life, all with a touch of levity. Thank you both for your friendship and encouragement. Here’s to many more years of collaboration and travel. My family has been an indispensible strength behind my studies. I cannot express the extent of my gratitude to my parents, Timothy and Allyson Cleath. Thank you for your unwavering support my whole life. Knowing that you believe in me and see the value in what I do gives me a firm foundation from which to tackle the adventures that are before me. You have ix

both modeled for me how to pursue a vocation with passion and excellence. I love you and think of you daily, even when I am far away. I wish to honor my grandparents on both sides of the family. I can only hope to live up to the example set by my paternal grandparents, Dr. Robert L. Cleath and Virginia Cleath. Both Grandpa and Grandma Cleath set a high standard for education in our family, creating a culture of learning for future generations of Cleaths. I am the second Dr. Cleath, but I hope I will not be the last. Grandma, your continuing drive to learn and challenge your intellect is an inspiration. Thank you for the financial and personal ways in which you have supported me. My mother’s parents, Arthur and Nora Chew, have always been there for me. Gung Gung, I miss you and wish you could be here to celebrate with me. I know you would be proud. Pau Pau, you have shown me both financially and personally that you value what I do, and I am honored to follow in your footsteps at UCLA. I am thankful for your practical grandmotherly concern over the years, and your friendship in more recent years. Additional thanks goes to my siblings, Stephen, Amy and John (and Timmy), and Bobby and Kezia. You know me, and how much my life has changed over the years; you know how much fun we can have together, and that goofiness will transcend any geographical distance between us. Thank you for always being a base I can come back to. Finally, I want to acknowledge all of my extended family and friends in San Luis Obispo, Los Angeles, and beyond. You are too many to name. You have been my cheerleaders, companions, listeners, and merrymakers in this marathon of a journey. I am especially grateful to Angie, Annie, Eduardo, Adam, and Amy, for being my urban family in California, and to Daphne, for walking through the tail end of this process with me. Can we all eat cake now? x

Vita 2000 B.A., French integrated with Biblical Studies and Theology Wheaton College Wheaton, IL 2006 M.A., Biblical Studies and Theology Fuller Theological Seminary Pasadena, CA 2008 Director of Advising Services, School of Intercultural Studies Fuller Theological Seminary Pasadena, CA 2008 Dean's Humanities Fellowship University of California at Los Angeles 2009-2012 Adjunct Instructor, Theological French Fuller Theological Seminary Pasadena, CA 2009-2012 Graduate Student Researcher University of California at Los Angeles 2010 Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) Award University of California, Los Angeles Modern Hebrew Ulpan Course, Conservative Yeshiva of Jerusalem 2011 Summer Graduate Research Mentorship University of California, Los Angeles 2012-2015 Teaching Associate University of California, Los Angeles 2013 Adjunct Instructor, Biblical Greek George Fox Evangelical Seminary Portland, OR 2013 Roter Research Fellowship Center for Jewish Studies University of California, Los Angeles 2014 Visiting Lecturer, Religious Studies University of California, Santa Barbara xi

2015 Mellon Pre-dissertation Fellowship University of California, Los Angeles 2015 Roter Research Fellowship Center for Jewish Studies University of California, Los Angeles 2015 Dissertation Year Fellowship, University of California, Los Angeles 2016 Adjunct Instructor, Biblical Hebrew George Fox Evangelical Seminary Portland, OR 2016 Research Fellow, Aramaic Papyri Elephantine Digitization Project, ERC Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Presentations and Publications Cleath, Lisa J. “Public Reading in Joshua 8:30-35: Fluidity and Continuity in an Oral-Written Text.” Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting. (San Antonio, Texas). November 2016. . “Public Reading in Nehemiah 8: Authorizing an Oral-Written Text.” European Association of Biblical Studies Conference. (Leuven, Belgium). July 2016. . “And All of the People Joined in the Covenant: A social study of public reading audiences in the Hebrew Bible.” European Association of Biblical Studies Conference. (Córdoba, Spain). July 2015. . “Towards an Israelite Theory of Public Reading.” European Association of Biblical Studies Conference. (Córdoba, Spain). July 2015. . "Reading Ceremonies in the Hebrew Bible: Text As Ritual Performance." International Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. (Vienna, Austria). July 2014. . "The Materiality of Text in Deuteronomy." International Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. (St. Andrews, Scotland). July 2013. . "Manasseh, Prayer of." The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Books of the Bible. (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press). 2012. .“Ben Sira as Hellenistic Scribe-Redactor.” European Association of Biblical Studies Conference. (Thessaloniki, Greece). August 2011. xii

CHAPTER ONE Introduction Scenes of public readings of “the book of the law” in the Hebrew Bible present a unique opportunity to access ancient ideologies of the social dynamics of authoritative texts. In the Hebrew Bible, Joshua 8:30-35, 2 Kings 22-23, and Nehemiah 7:72b-8:18 narrate key public reading events. The construction of each narrative emphasizes the characterization of the audience by listing out the groups of the populace and their leaders who participate in the reading event. These people groups serve as the addressees of the book of the law, which in turn acts to form the identity of the group. After crossing over into the land, in Josh 8, Joshua inscribes the book of the law and pronounces it to the people, including the resident aliens, women, and children with the citizens of Israel. The Josiah narratives in 2 Kgs 22-23 and 2 Chr 34-35 recount exilic and post-exilic versions of the finding of the book of the law in the temple, and its royal enactment through a covenant reading to all socio-economic classes of the Judahite populace. Finally, Neh 8 affirms the reconstruction of Persian period Judean identity, including both men and women, through the reading and study of the law under priestly leadership. In each of the instances depicting a public reading in the Hebrew Bible, it is in a covenant renewal scene at a transitional point in history for the Israelites. These narratives imbue a purpose in the ceremony that sets both the document and the event apart from a common scribal reading. The covenant renewal element of the ceremonies is common to each, but the accounts also select strikingly similar performative context elements. Insofar as all of these accounts emphasize the geographical venue and social addressees of the reading, this raises the question “How do these chronologically disparate narratives each utilize an authoritative text to construct 1

social reality?” Taking a historical-literary analysis of the narratives highlights which characteristics biblical redactors selected to portray the people and the text on these noteworthy occasions. This study will argue that each narrative presents the authoritative text in reflexive relationship to its audience, while manipulating the specific functions of the text and its locus of authority according to the ideology of each chronologically and politically differentiated context. The reading ceremonies portray the authoritative texts as co-forming their social environment in a specific manner. Although they share an emphasis on “all of the people” joining in the reading, each of the ceremonies in Josh 8, 2 Kgs 23, and Neh 8 describe this public with a particularized list of subgroups in attendance. In each case, the defined composition of “the people,” and thus the entire delimited community, identifies key characteristics of the sociohistorical perspectives in each text – the projected geographical, institutional, socio-economic boundaries of the covenant’s addressees. The conception of the covenant as addressing the entirety of the people has roots in the ancient Near Eastern loyalty oath genre, but loyalty oaths have the purpose of establishing a suzerain’s authority over the addressees. It is evident in these narratives that the Israelite community utilized a document-based public address to redefine the limits of its own community boundaries throughout the exilic and post-exilic periods and thus to refocus the purpose of covenant upon internal unity. Although these ceremonies as a set are unique because they alone bring together elements of communal unity and collectivity as executed via a written document, the exilic and post-exilic narratives differ in the way they wield the documents. For example, the exilic-redacted Josiah account in 2 Kgs 22-23 authorizes the book of the law as an oral word from God, and wields its authority to particularize the textual impact for the present day of the Judahite community. By contrast, Neh 8 depicts the book of the law as a written law transmitted from God through Mosaic agency, which serves in the narrative 2

to define the Persian period Judean community specifically as southern descent Babylonian exiles returned to the land. I. Relationship to Previous Scholarship Since the late nineteenth century, biblical scholarship on these narratives has focused on reconstructing history: the source-critical history of each account, and the historicity of the reported events.1 For example, Frank Moore Cross established a line of inquiry which purposed to unite the question of an original edition of the Deuteronomistic History with the historicity of biblical events, by dating such an edition to the reform of Josiah. Several generations of scholarship have followed his lead in this pursuit: We are pressed to the conclusion by these data that there were two editions of the Deuteronomistic History, one written in the era of Josiah as a programmatic document of his reform and of his revival of the Davidic state The second edition, completed about 550 B.C., not only updated the history by adding a chronicle of events subsequent to Josiah’s reign, it also attempted to transform the work into a sermon on history addressed to Judaean exiles.2 Cross exemplifies a biblical scholarship that tended to limit the exploration of the Deuteronomistic History and post-exilic literature to questions of historicity. This scholarship established the historical contexts in which biblical literature should be interpreted, so in each chapter I provide an overview of the main arguments of previous scholarship that are pertinent to the social contexts constructed in the respective narratives. This study works with the goal of examining the rhetoric of the final form of biblical accounts, while respecting the foundation that historical critical scholarship has provided for literary work. I will build upon historical critical 1 Archaeologist Lawrence Stager minimizes the value of literature for historical investigation, stating, “Documents become a source of information about the human past only insofar as they can be made ‘relevant’ to the question or problematic posed by the historian” (“The Archaeology of the Family in Ancient Israel,” BASOR, no. 260 (1985): 1). 2 Frank Moore Cross, “The Themes of the Book of Kings and the Structure of the Deuteronomistic History,” in Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), 287. 3

scholarship, but diverge in method by applying literary analysis. Through this departure, I do not hope to reconstruct historical events or text sources, but rather the ideology of authoritative text that is represented in the literature. One key point of divergence from previous scholarship will be my interpretation of the social significance of written documents. When it comes to the chronological trajectory of authoritative texts within Hebrew literature, writing becomes markedly more common in the Jewish community from the Hellenistic period forward. It is the pre-exilic, exilic, and Persian periods represented within the Hebrew Bible that present a more enigmatic tangle of data.3 It is more difficult to confidently date the composition and redaction of those texts, and there is less comparative data for the exilic and pre-exilic periods. This study will attempt to fill out exilic, if not pre-exilic, ideologies of authoritative text through analysis of the Josh 8 and 2 Kgs 22-23 accounts. In doing so, however, I will seek to move beyond previous definitions of textual significance, since they have primarily taken the book of the law as solely having semantic value. Recent studies such as James W. Watts’s work on the iconic and performative functions of texts and Webb Keane’s observations regarding the potentially reflexive interpretation of objects have offered valuable insights into the characteristics of texts beyond their semantic functions. These works, however, have not yet been brought to bear upon the analysis of public readings in the Hebrew Bible. I will delve into the iconic, performative, as well as semantic, means by which the narratively-portrayed texts co-create their communities in pre-exilic through post-exilic literature. 3 Wilfred Cantwell Smith, for one, has identified the advent of scripturalization as the focal point of religious practice in the late antique Mediterranean world, starting from the Hellenistic period and a second century BCE concept of a sacred book with supreme authority (“Scripture as Form andConcept: Their Emergence for the Western World,” in Rethinking Scripture, ed. Miriam Levering (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 29–57). 4

II. Method: Characterization as Literary Analysis The literary analysis that I propose as a method is a study of characterization deriving from the world of narrative criticism. Although I will take historical context into account, this analysis takes the final form of the narratives as the point of departure: “Narrative criticism works with the text as ‘world-in-itself.’ Other approaches tend to fragment, in part because their purpose is to put elements of the text into contexts outside the text Narrative criticism brackets these historical questions and looks at the closed universe of the story-world.”4 For each reading ceremony narrative, I will examine the characterization of the people and the characterization of the text. Past studies of Josh 8 and 2 Kgs 22-23 have not utilized literary analysis to address how the narratives construct the authority of the text in its relationship to the people. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi has only cursorily examined the characterization of the text in light of the characterization of the people in Ezra-Nehemiah.5 This study posits that the people and the book of the law in the Hebrew Bible merit an examination of their place and functioning within the narrative framework of the reading ceremony accounts. Some contemporary literary theorists, particularly structuralists, have declared the individual character “dead,” but Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan asks, “do not even the minimal depersonalized characters of some modern fiction ‘deserve’ a non-reductive theory which will adequately account for their place and functioning within the narrative network?”6 In 4 David Rhoads, “Narrative Criticism and the Gospel of Mark,” JAAR L, no. 3 (1982): 413. 5 See, for example, Tamara Eskenazi, In an Age of Prose: A Literary Approach to Ezra-Nehemiah (Atlanta: Scholar’s Press, 1988); Tamara Eskenazi, “Ezra-Nehemiah: From Text to Actuality,” in Signs and Wonders: Biblical Texts in Literary Focus, ed. J. Cheryl Exum (Atlanta, 1989), 165–98; Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, “Imagining the Other in the Construction of Judahite Identity in Ezra-Nehemiah” (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). 6 Rimmon-Kenan’s work has been influenced by Anglo-American New Criticism, Russian Formalism, French Structuralism, and the Tel Aviv School of Poetics and the Phenomenology of Reading. Hers is one of several handbooks that present narrative fiction according to its themes rather than specific schools of thought (Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics (New York: Routledge, 1983), 31). 5

this endeavor, the characters need not exist in some objective personal sense, especially since I am primarily concerned with the people as a collective and the text as a concept – both abstractions within the narrative. The character, therefore, is a construct accessed through its portrayal in the narrative. Structuralist and text critic Roland Barthès explored how the reader puts the character together from the network of character traits given in the narrative.7 For Rimmon-Kenan, narratives express character traits in three basic modes: direct definition, indirect presentation, and reinforcement by analogy.8 Direct definition in the biblical covenant ceremonies starts with the terminology applied to the character.9 For example, in Josh 8, the people are called “the sons of Israel,” whereas in 2 Kgs 22-23, they are “the residents of Judah.” Likewise, the book of the law is variously referred to as “the book of the covenant” or “the law given to Israel through Moses.” The differences between these terms and their usage in their narratological contexts communicate the ideological perspectives constructed by the final form of the narratives. In addition, the direct characterization of the people in each of these reading ceremonies is also given through a list of the subgroups of participants. This study examines their characterization via analysis of the lists and comparison of the lists to other populace lists in ancient Near Eastern loyalty oaths. 7 Roland Barthes, S/Z (Paris: Seuil, 1974). 8 Utilizing Rimmon-Kenan, Tamara Cohn Eskenazi discusses these categories for analyzing characterization in In an Age of Prose: A Literary Approach to Ezra-Nehemiah, 128; see also Rimmon-Kenan, Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics, 59–69. 9 Rimmon-Kenan defines direct definition as naming “the trait by an adjective (e.g. ‘he was good-hearted’), an abstract noun (‘his goodness knew no bounds’), or possibly some other kind of noun (‘she was a real bitch’) or part of speech (‘he loves only himself’).” This method must be adapted to the ancient literature and genre with which we are dealing, which often does not employ these kind of statements in the historical narratives of the reading ceremonies, but nevertheless, they contain other direct descriptions (Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics, 59). 6

Indirect presentation of a character “does not mention the trait but displays and exemplifies it in various ways, leaving to the reader the task of inferring the quality they imply.”10 In each reading ceremony, one of the prominent means of indirect characterization is the geographical environment, which firmly establishes a socio-political setting for the narrative. Josh 8 takes place at Shechem, while 2 Kgs 22-23 and Neh 8 are set at venues in Jerusalem. In each of these three cases the specific location communicates a great deal regarding the boundaries of the community and their hierarchy of leadership. The people’s indirect characterization is portrayed through the relationships constructed between them, their leaders, and the text of the law. Indirect presentation furthermore includes examination of any actions executed in the course of the narrative. Theorists like Vladimir Propp and Algirdas Greimas subordinate the character to their actions, while some structuralists assert the primacy of the character over any actions they take.11 I will seek to avoid imposing either model upon these selective narratives, but rather inquire whether the narrative emphasizes action on the part of the people or the book of the law, or whether they are more passive in the events as they are described. As Rimmon-Kenan states, “Different hierarchies may be established in different readings of the same text but also at different points within the same reading Hence it is legitimate to subordinate character to action when we study action but equally legitimate to subordinate action to character when the latter is the focus of our study.”12 In addition to indirectly depicting the characters through their ceremony setting and the actions taken therein, the covenant reading ceremony accounts also characterize the book of the 10 Ibid., 60. 11 Ibid., 34–35. 12 Ibid., 36. 7

law through reference to its physical appearance (i.e., on stone, as in Josh 8, or as a sēpher scroll in Neh 8). Due to the sensory descriptions of the reading venue and textual artifacts, analysis of the narratological indirect characterization will be conducted with reference to portrayed materiality. This emphasis on “materiality” has been well developed by Keane and his fellow anthropologists.13 Just as performance theory would suggest consideration of the environmental factors of the reading,14 so materiality encourages analysis of all sensory descriptions within the depicted scene, the selective fictional materiality the narrative creates. Since written texts by nature have a physical form, human interactions with their material properties may be analyzed to discern underlyin

University of California, Los Angeles 2012-2015 Teaching Associate University of California, Los Angeles 2013 Adjunct Instructor, Biblical Greek George Fox Evangelical Seminary Portland, OR 2013 Roter Research Fellowship Center for Jewish Studies University of California, Los Angeles 2014 Visiting Lecturer, Religious Studies

Los Angeles County Superior Court of California, Los Angeles 500 West Temple Street, Suite 525 County Kenneth Hahn, Hall of Administration 111 North Hill Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Los Angeles, CA 90012 Dear Ms. Barrera and Ms. Carter: The State Controller’s Office audited Los Angeles County’s court revenues for the period of

Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center 757 Westwood Pl. Los Angeles CA 90095 University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center 757 Westwood Pl. Los Angeles CA 90095 University of Southern California (USC) 1500 San Pablo St. Los Angeles CA 90033-5313 (323) 442-8500 USC University Physicians 1500 San Pablo St. Los Angeles CA 90033-5313

1Department of Urban Planning, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, USA 2Department of Asian American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, USA Corresponding Author: Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Department of Urban Planning, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Box 951656, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA.

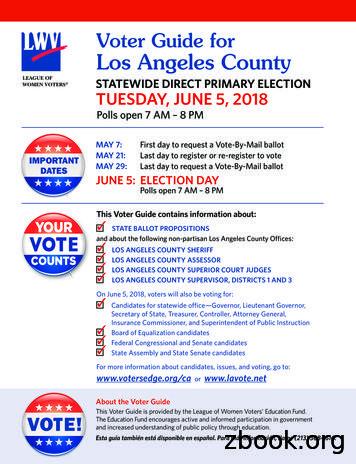

This Voter Guide contains information about: STATE BALLOT PROPOSITIONS and about the following non-partisan Los Angeles County Offices: LOS ANGELES COUNTY SHERIFF LOS ANGELES COUNTY ASSESSOR LOS ANGELES COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT JUDGES LOS ANGELES COUNTY SUPERVISOR, DISTRICTS 1 AND 3 On June

Los Angeles Los Angeles Unified Henry T. Gage Middle Los Angeles Los Angeles Unified Hillcrest Drive Elementary Los Angeles Los Angeles Unified International Studies Learning Center . San Mateo Ravenswood City Elementary Stanford New School Direct-funded Charter Santa Barbara Santa Barbar

Jun 04, 2019 · 11-Sep El Monte (El Monte Community Center Los Angeles/San Gabriel Valley 18-Sep South Los Angeles (Exposition Park-California Center) Los Angeles 20-Sep Palmdale (Chimbole Cultural Center) Los Angeles/Antelope Valley, Santa Clarita 25-Sep San Fernando (Alicia Broadous-Duncan Multi-Purpose Senior Center) Los Angeles/ San Fernando Valley

aDepartment of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA. E-mail: happyzhou@ucla.edu; yangy@ ucla.edu bCalifornia NanoSystems Institute, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90025, USA Cite this: DOI: 10.10

Artificial intelligence is the branch of computer science concerned with making comput-ers behave like humans, i.e., with automation of intelligent behavior. Artificial intelli- gence includes game playing, expert systems, natural language, and robotics. The area may be subdivided into two main branches. The first branch, cognitive science, has a strong affiliation with psychology. The goal is .