Mot Vat Ons Of Sport Volunteers N England Motivations Of .

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in EnglandMotivationsof Sport Volunteersin EnglandA review for Sport EnglandDr. Geoff Nichols, Caroline Knight,Helen Mirfin-Boukouris & Cumali UriUniversity of SheffieldDr. Eddy HoggUniversity of KentRyan StorrVictoria University, AustraliaJanuary 2016

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in Englandii

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in EnglandSummaryThis review is the first to combine the findings of commercial reports and academicresearch into the motivations of sports volunteers with general theory understanding volunteers and volunteering. This provides a broader understanding ofvolunteering in sport. It provides a useful resource for anyone in the planning,management and delivery of sports volunteering and a stepping stone for furtherresearch.Volunteering and sports participation are both extremely popular activities forEnglish adults. Volunteering in support of sports teams, clubs and other organisations is one of the most commonly undertaken types of volunteering in England.Within ‘sports volunteering’ exists an extremely wide range of roles — coach,captain, secretary, chairman, treasurer, administrator, fundraiser, washing thekit, transporting children, and a range of other more niche and sport-specificactivities.Volunteering is best understood as a process through which volunteers move,not necessarily in a linear or a constant way, over the course of their lives. Thisvariation over time can be understood as a consequence of particular values,circumstances and experience. Similarly, people move through different typesof sports participation in response to personal circumstances and experience.The processes of moving though volunteering in sport and participating in sportrun in parallel because the two are usually connected. The sport volunteeringroles identified above — which involve different demands of time and skills — aremotivated by different factors at different stages of people’s lives. Sports volunteering and participation can be understood as a consequence of different formsof social capital.Thus promoting volunteering is best understand as facilitating a developmental progression through roles, rather than as targeting market segments withparticular potential.Theory helps us understand changes in the nature of volunteering over people’slives. A distinction between unpaid work, activism and serious leisure as differentforms of volunteering can be applied to the different roles that people take withinsports. For young people with professional aspirations, either within sport or morebroadly, volunteering as unpaid work enables them to develop skills and demonstrate competence which will be of economic value to them. For slightly oldervolunteers, volunteering offers the opportunity to support the sport they love andto give back to their team or club or to support their children’s interests — a form ofmutual aid or ‘activism’. For older volunteers, who may have stopped participatingin the sport ‘on the field’ but want to stay involved, taking on new roles offers theopportunity to explore new opportunities and learn new skills — a form of ‘seriousleisure’. Each of these different roles has different rewards and motivations.iii

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in EnglandThis review of literature on sports volunteering applies these insights. The review, alongwith consultation with key individuals across the world, identified the following themes whichstructure this report: Descriptive statistics on volunteers, including who volunteers in sport, what they do andhow the nature of sports volunteering changes between roles. Motivations of volunteers at club level, which considers a range of literature on sportsvolunteer motivations and looks to develop a typology of sports volunteers.Motivations of Sport Volunteers in England Volunteers at mega-events, exploring how volunteering at events such as Olympic andCommonwealth Games differs from other forms of sports volunteering and may be relatedto it. Volunteers at regional events, which in many ways closely resembles club level volunteering as it is more linked to passion for the sport than is mega-event volunteering. Coaches as volunteers, and in particular the transition from player to volunteer coach andthe role of parents as coaches. Volunteers in education and youth organisations, although we found no literature on sportsvolunteers in education, and the literature on youth organisations did not separate sportfrom the other activities they provide as a medium for developing young people. Young people and students as sports volunteers, with the literature partially contradictingthe prevailing view that young people volunteer for instrumental, careerist reasons. Thesemotives are significant, but so are friends and a passion for sport. Older people as sports volunteers, who are often the core of sports clubs or organisations,fulfilling roles that require significant time commitments and a range of skills. Volunteers’ effect on the experience of sports’ participants and promoting motivation, whichincludes the positive impact of enthusiasm, and a passion for the sport and expertise; anda negative impact from the inherent nature of volunteer organisations to attract similarpeople. The impact of volunteers extends to amateur coaching, which can provide cheapinstruction, or a negative experience. Explanations of volunteers moving between roles, particularly over their lives as circumstances change and also in response to changes within clubs and sports.To develop these themes an initial literature search found 131 relevant items of research:abstracts of these are collected in Appendix 1 (see Contents list pp. vi–xii).Fifty nine of the initial items were selected for review in depth.Of those in-depth reviews, 14 reviews supporting Results section 4.1 (the roles of sportsvolunteers) and section 4.2 (motivations of sports clubs volunteers) are included in Appendix2 (see Contents list p. xii).Following analysis presented in the Results section, we make suggestions for future researchinto sports volunteers, in particular highlighting the need for work on how roles change overtime and how this affects volunteers, sports and participants.iv

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in EnglandContentsSummary . . . . . iiiIntroduction . . . . 11. The role of volunteers in sport and their importance to Sport England’spromotion of participation . . 1Table 1.1Formal volunteering in sport in England, 2002 . . . . . . . . . 12. Volunteering in England . . 32.1 Understanding volunteering in relation to leisure and sport . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Figure 2.1 A three-perspective model of volunteering . . . . . . . . . . 32.2 Numbers and trends in volunteering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Figure 2.2 Formal volunteering and sport volunteering by region . . . . . . . 82.3 Overview of motivations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Figure 2.3 Four groups of volunteer impulses (Hardill, Baines & Perry, 2007) . . 92.4 Researching motivations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .112.5 Changes in volunteering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142.6 Summary of influences on volunteering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .193. Methods le 3.1Sources selected for detailed review. . . . . . . . . . . . 214. Results 4.1 The roles of sports volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Table 4.1The percentage of sports volunteers involved in different roles,and their average time commitment per week, according toeach of the 10 studies which provided this information. . . . . 234.2 Motivations of sports club volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Table 4.2The motivations of sports volunteers according to each of the12 studies which provided this information. . . . . . . . . 274.3 Motivations of mega-event volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Table 4.3a Ranking of volunteer motivations — Vancouver 2010 andLondon 2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32Table 4.3b Motivations of 2002 Commonwealth Games volunteers. . . . . . 33Table 4.3c Groupings of 2012 Olympic volunteer motivations . . . . . . . 34Table 4.3d Motivations for becoming sports volunteers, of volunteersat the 2002 Commonwealth Games who had previouslyvolunteered in sport . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 364.4 Motivations of regional event volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 404.5 Motivations of coaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .434.6 Motivations of volunteers in education and youth organisations . . . . . . . . . . . .444.7 Motivations of young people and students as sports volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . 47Table 4.7Changes in motives over 9 month’s experience of the Millenniumvolunteers programme. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 494.8 Motivations of older volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .504.9 Volunteers’ effect on the sporting experience of participants, and promotingmotivation of volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Figure 4.9 Members’ views of the sport club’s purpose (Nichols, 2014) . . . . 545. Conclusions. Clustering volunteers and explaining sports volunteering . . . . . . . 56Figure 5.1 Theoretical model of ‘sporting capital’. . . . . . . . . . . . 596. Suggestions for further research . . . . . . . . . 60

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in EnglandReferences . . . . 62Appendix 1 Abstracts (Initial Research) . . . . . . . 691.ADAMS, A., & DEANE, J. (2009). Exploring formal and informal dimensions of sportsvolunteering in England. European Sport Management Quarterly, 9, 119–140. . . . . 692.ALEXANDER, A., KIM, S.B., & KIM, D.Y. (2015). Segmenting volunteers by motivation inthe 2012 London Olympic Games. Tourism Management, 47, 1–10. . . . . . . . . 693.ALLEN, J.B., & SHAW, S. (2009). “Everyone rolls up their sleeves and mucks in”: Exploringvolunteers’ motivation and experiences of the motivational climate of a sporting event.Sport Management Review, 12, 79–90 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 704.BENSON, A.M., DICKSON, T. J., TERWIEL, A., & BLACKMAN, D. (2014). Training ofVancouver 2010 volunteers: A legacy opportunity? Special Issue: The Olympic Legacy;Contemporary Social Science: Journal of the Academy of Social Sciences,9, 2, 210–226 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 705.BREUER, C., WICKER, P., & VON HANAU, T. (2012). Consequences of the decrease involunteers among German sports clubs: is there a substitute for voluntary work?International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 4, 173–186. . . . . . . . . . . 716.BURGHAM, M., & DOWNWARD, P. (2005). Why volunteer, time to volunteer? A casestudy from swimming. Managing Leisure, 10, 79–93. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 717.BUSSER, J.A., & CARRUTHERS, C.P. (2010). Youth sport volunteer coach motivation.Managing Leisure, 15, 128–139 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 718.BYERS, T. (2013). Using critical realism: A new perspective on control of volunteers insport clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13, 5–31 . . . . . . . . . . 729.COLEMAN, R. (2002). Characteristics of volunteering in UK sport: Lessons from cricket.Managing Leisure, 7, 220–238 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10.CUSKELLY, G. (2004). Volunteer retention in community sport organisations. EuropeanSport Management Quarterly, 4, 59–76 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7311.CUSKELLY, G., & O’BRIEN, W. (2013). Changing roles: applying continuity theory tounderstanding the transition from playing to volunteering in community sport.European Sport Management Quarterly, 13, 54–75. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7312.CUSKELLY, G., MCINTYRE, N., & BOAG, A. (1998). A longitudinal study of the development oforganizational commitment amongst volunteer sport administrators. Journal of SportManagement, 12, 181–202. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7413.DAVIS SMITH, J. (2000). ‘Volunteering and social development’, Voluntary Action 3, 1, 1–12 . . 7414.DAWSON, P., & DOWNWARD, P. (2013). The relationship between participation in sportand sport volunteering: An economic analysis. International Journal of SportFinance, 8, 75–92. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7515.DE SOUZA, T. (2005). The role of higher education in the development of sports volunteers.Voluntary Action 7, 1, 81–98. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7516.DEAN, J. (2014). How structural factors promote instrumental motivations within youthvolunteering: a qualitative analysis of volunteer brokerage. Voluntary SectorReview, 5, 231–247. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.DEANE, J., MAWSON, H., CRONE, D., PARKER, A., & JAMES, D. (2010). ‘Where are thefuture sports volunteers? A case study of Sports Leaders UK’, LSA NewsletterNo. 86, July 2010: 29–32 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7618.DICKSON, T.J., BENSON, A.M., BLACKMAN, D.A., & TERWIEL, A.F. (2013). It’s All Aboutthe Games! 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games Volunteers. EventManagement, 17, 77–92. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7619.DICKSON, T.J., BENSON, A.M., & TERWIEL, F.A. (2014). Mega-event volunteers, similaror different? Vancouver 2010 vs London 2012. International Journal of Event andFestival Management, 5, 164–179 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7720.DOHERTY, A. (2005). A profile of community sport volunteers. Unpublished report forParks and Recreation Ontario and Sport Alliance of Ontario . . . . . . . . . . . 7721.DOHERTY, A. (2005). Volunteer management in community sports clubs — a study ofvolunteers’ perceptions. Unpublished report for Parks and Recreation Ontario andSport Alliance of Ontario. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .vi. 72. 75. 79

Motivations of Sport Volunteers in England22.DOHERTY, A. (2009). The volunteer legacy of a major sport event. Journal of PolicyResearch in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1, 185–207 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7923.DOHERTY, A., & JOHNSON, S. (2001). Development of scales to measure cognitiveand contextual influences on coaching entry. Avante, Vol.7, No. 3, pp. 41–60 . . . . . 7924.DOHERTY, A., PATTERSON, M., & VAN BUSSEL, M. (2004). What do we expect? Anexamination of perceived committee norms in non-profit sport organisations.Sport Management Review, 7, 109–132 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8025.DOWNWARD, P., & RALSTON, R. (2005). Volunteer motivation and expectations priorto the XV commonwealth games in Manchester, UK. Tourism and HospitalityPlanning & Development, 2, 17–26 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8026.EGLI, B., SCHLESINGER, T., & NAGEL, S. (2014). Expectation-based types of volunteersin Swiss sports clubs. Managing Leisure, 19, 359–375. doi:10.1080/13606719.2014.885714. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8027.ELEY, D., & KIRK, D. (2002). Developing citizenship through sport: The impact of asport-based volunteer programme on young sport leaders. Sport Educationand Society, 7, 151–166. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8128.ELLIS PAINE, A., MCKAY, S., & MORO, D. (2013). Does volunteering improveemployability? Insights from the British Household Panel Survey and beyond, 4, 3,355–376. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8129.ENGELBERG, T., SKINNER, J., & ZAKUS, D. (2014). What does commitment mean tovolunteers in youth sport organizations? Sport in Society, 17, 52–67. . . . . . . . 8230.ENGELBERG, T., ZAKUS, D. H., SKINNER, J.L., & CAMPBELL, A. (2012). Defining andmeasuring dimensionality and targets of the commitment of sport volunteers.Journal of Sport Management, 26, 192–205. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8231.FAIRLEY, S., KELLETT, P., & GREEN, B.C. (2007). Volunteering abroad: Motives fortravel to volunteer at the Athens Olympic Games. Journal of SportManagement, 21, 41–57. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8232.FELTZ, D.L., HEPLER, T.J., ROMAN, N., & PAIEMENT, C. (2009). Coaching efficacy andvolunteer youth sport coaches. Sport Psychologist, 23, 24–41. . . . . . . . . . . 8333.GASKIN, K. (2004). Young people, volunteering and civic service: A review of theliterature. Institute for Volunteering Research. . . . . . . . . . . .8334.GASKIN, K. (2008). A winning team? The impacts of volunteers in sport. Institutefor Volunteering Research and Volunteering England . . . . . . . . . . 8435.GRATTON, C. NICHOLS, G. SHIBLI, S., & TAYLOR, P. (1997). Valuing volunteersin UK sport. London: Sports Council. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84.36.GREEN, B., & CHALIP, L. (2004). Paths to volunteer commitment: Lessons from theSydney Olympic Games. In R. A. Stebbins & M. Graham (Eds), Volunteering asleisure/ leisure as volunteering: An international assessment (pp. 49–67).Wallingford: CABI Publishing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8437.GRIFFITHS, M.A., & ARMOUR, K.M. (2013). Volunteer sport coaches and their learningdispositions in coach education. International Journal of Sports Science &Coaching, 8, 677–688 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38.GROOM, R., TAYLOR, W., & NELSON, L. (2014). Volunteering insights: Reportfor Sport England, March 2014 ight-project-for-sport-engla

sports. For young people with professional aspirations, either within sport or more broadly, volunteering as unpaid work enables them to develop skills and dem-onstrate competence which will be of economic value to them. For slightly older volunteers, volunteering offer

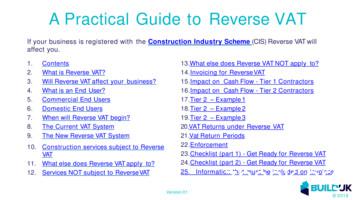

A Practical Guide to Reverse VAT 1. Contents 2. What is Reverse VAT? 3. Will Reverse VAT affect your business? 4. What is an End User? 5. Commercial End Users 6. Domestic End Users 7. When will Reverse VAT begin? 8. The Current VAT System 9. The New Reverse VAT System 10. Construction services subject to Reverse VAT 11. What else does Reverse VAT apply to? 12. Services NOT subject to .

VAT ( ) C VAT EU Tax Authorities * Electronic Interface EU , VAT EU-established Intermediary (Tax Representative) . Tax Representative VAT Return VAT EU Tax Authorities VAT & IOSS No. Commercial Invoice Data DHL IOSS EU Tax Authorities VAT Return VAT 10

1. VAT inclusive A The VAT received by a business from sales of goods or income earned. 2. VAT vendor B Payments which are made twice in a month. 3. Input tax C VAT is excluded in the marked price. 4. VAT invoice D Receipts issued by SARS for VAT payments. 5. VAT exclusive E VAT is payable when the

In general, the VAT due equals output VAT less input VAT. As a rule, input VAT may be deducted from output VAT when a taxpayer receives an invoice for goods or services purchased, or in the two subsequent VAT reporting periods. However, to deduct input VAT the

8. Withholding VAT / VAT Deduction at Source 27 9. Filing VAT Return / Turnover Tax Return 28 10. Concept of Fair Market Value (FMV) 30 11. VAT Exempted Goods & Services 31 12. Interest & Penalty 32 13. Filing and Disposal of Appeal 33 14. VAT Refund for Diplomatic Mission / International

total for the tax or VAT. The purpose of the VAT fields at the header level is to store the overall total tax or VAT amounts represented on the invoice image. Assuming the VAT rate is identical for all line items, the system will auto-distribute the VAT to the gross amount for each li

VAT, or Value Added Tax, is a tax that is charged on most goods and services that VAT registered businesses provide in South Africa. Unlike other taxes, VAT is collected on behalf of SARS by registered businesses. Once you’re registered for VAT, you must charge the applicable rate of VAT

EU SPORT POLICY: EVOLUTION EU SPORT POLICY: EVOLUTION 2011: THE COUNCIL WORK PLAN ON SPORT On May 20, the EU Sport Ministers adopted a Work Plan for Sport. The Council Work Plan sets out the sport ministers' priorities in the field of sport for the next three years (2011-2014) and creates new working structures.