Chemistry - Leaving Certificate Teachers Reference .

Teacher’s Reference HandbookCHEMISTRYA NR O I N NOIDEACHAISAGUS EOLAÍOCHTADEPARTMENT OFEDUCATIONAND SCIENCEDepartment of Education and Science: Intervention Projects in Physics and ChemistryWith assistance from the European Social Fund

CONTENTSAcknowledgementsIntroductionGender and ScienceModule 1Atomic Structure and Trends in the Periodic Table of the ElementsModule 2HydrocarbonsModule 3Industrial ChemistryModule 4Environmental Chemistry - WaterModule 5Stoichiometry IModule 6Alcohols, Aldehydes, Ketones and Carboxylic AcidsModule 7Stoichiometry IIModule 8Atmospheric ChemistryModule 9MaterialsModule 10Some Irish Contributions to ChemistryIndex

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis handbook has been produced as part of theDepartment of Education and Science’s scheme ofIntervention Projects in Physics and Chemistry.These projects were commissioned by theDepartment’s Equality Committee, chaired by MrDenis Healy, Assistant Secretary General. Theprojects have been funded by the Department withassistance from the European Social Fund.Editorial BoardAuthors of ModulesMr Seán Ó Donnabháin, SeniorDepartment of Education and Science.Dr Fiona Desmond, College of Commerce, CorkDr Tim Desmond, Department Inspector andformerly of Carrigaline Community School, CorkMr Brendan Duane, Holy Family Secondary School,Newbridge, Co. KildareMr Declan Kennedy, Education Department,University College Cork and formerly of Scoil Muire,Cobh, Co. CorkMr John Toomey, The High School, DublinThe section on ‘Gender and Science’ was written byDr Sheelagh Drudy, Education Department, NUIMaynooth, in association with Ms Marion Palmer,Dun Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design andTechnology and formerly of Mount Temple School,Dublin.The section on ‘Some Irish Contributions toChemistry’ was written by Dr Charles Mollan,Samton Ltd, Newtownpark Avenue, Blackrock, Co.Dublin.Mr Declan Kennedy, Education Department,University College Cork and formerly of Scoil Muire,Cobh, Co. CorkMr George Porter, Beneavin College, Dublin, onsecondment to the Department of Education andScienceInspector,The Department of Education and Science isgrateful to the following for the provision ofadditional material and for their expert advice andsupport at various stages of the preparation of thishandbook.Mr Paul Blackie, Athlone Institute of TechnologyMr Oliver J. J. Broderick, St Augustine’s College,Dungarvan, Co. WaterfordDr Peter Childs, University of LimerickMr Peter Desmond, IFI, Cobh, Co. CorkMr Bill Flood, IFI, Arklow, Co. WicklowMr Randal Henly, formerly of Mount Temple School,DublinDr Paula Kilfeather,Drumcondra, DublinStPatrick’sCollege,Mr Pat McCleerey, Premier Periclase, Drogheda,Co. Louth

Dr Andy Moynihan, Sligo Institute of TechnologyDr Brian Murphy, Sligo Institute of TechnologyMr Padraic Ó Cléireacháin, formerly of St McNissi’sCollege, Garron Tower, Co. AntrimDr Ann O’Donoghue, Sligo Institute of TechnologyDr Adrian Somerfield, formerly of St Columba’sCollege, DublinMr Terry Spacey, IFI, Arklow, Co. WicklowMr Peter Start, University College, DublinThe Department of Education and Science alsowishes to acknowledge the provision of materialfrom the following sources.Chemistry in Britain; Journal of Chemical Education;New Scientist; Pan Books Ltd; Prentice-HallInternational; School Science Review; TimesNewspapers Ltd.

INTRODUCTIONThis handbook has been produced as part of theDepartment of Education and Science’s Equality ofOpportunity Programme. The project developed outof the Department’s scheme of InterventionProjects in Physics and Chemistry which wasimplemented from 1985 with a view to increasingthe participation of girls in the study of the physicalsciences. It is hoped that the material contained inthis book will assist teachers in presentingchemistry in a manner which will give duecognisance to gender differences in relation tointerests and attitudes. It is also hoped that thematerial will help teachers in their continuing questto develop new approaches to their teaching whichwill make chemistry more interesting and excitingfor all their students.International trends in chemical education showattempts being made to develop syllabi whichincorporate an appreciation of the social,environmental and technological aspects ofchemistry. Chemical educators throughout the worldare attempting to make students aware ofhow mankind benefits from the advances beingmade in chemistry. In developing this handbookclose attention has been paid to theseinternational trends.The importance of science in general, andchemistry in particular, in today’s society should beconsidered when relevant throughout the course. Asin the syllabus, considerable emphasis has beenplaced on the social and applied aspects ofchemistry. In engaging the interest of students inchemistry it is very important that significantemphasis be placed on the ‘human face’ ofchemistry. Students should be aware that chemistryhas an increasingly important role to play inindustry, medicine, entertainment and in the home.The chemical industry has added immeasurably tothe quality of our lives through the development ofnew materials, new and improved pharmaceuticals,improved quality of drinking water and foodproducts, etc.The individual modules making up this handbookhave been selected around the content andstructure of the syllabus to provide easy access toresource material in a way which supports theimplementation of the course. However, it isimportant to realise that these modules do notdefine the syllabus. They do not determine thescope of the syllabus nor the depth of treatment thatis required or recommended. Rather, each moduleis designed to provide additional backgroundinformation for teachers. Each module containssuggestions on the teaching methods that theauthors have found beneficial over the years andgives details of student experiments and teacherdemonstrations. Worked examples are includedwhich the teacher may find useful in the class roomor for homework.It is not intended that this book be used as atextbook or be read from cover to cover. Rather, it isintended that it be used as a reference handbook toassist teachers in their task of conveying theexcitement and fascination of chemistry.Chemistry is an experimental subject. Generalprinciples and concepts are more easily understoodif they are demonstrated in the laboratory. Theproperties of particular substances are more fullyappreciated if the student has the opportunity to

examine them and investigate relevant reactions atthe laboratory bench. There is no better way to‘bring chemistry to life’ than with suitable laboratorypractical work. While it is vitally important thatappropriate safety precautions be taken at all timesit is also important that students be encouraged toapproach practical chemistry in a positive andenthusiastic manner.The material in this handbook is arranged into tenmodules plus a section on Gender and Science(see Contents). Each module is paginatedindependently. One index is provided for all thematerial, with page numbers preceded by a numberto indicate the module. Thus, for example, ‘2: 47’refers to Module 2, page 47.All of the content is also provided on the attachedCD, along with the material from the PhysicsHandbook. It is intended that this will facilitateteachers in finding specific items of interest and inmaximising on the use of the material in theirclasses. To this end teachers may print selectedsections from the CD for class handouts oroverhead transparencies. They may alsoincorporate selected topics into on-screenpresentations and into class materials prepared inother software packages.All the material in this publication is subject tocopyright and no part of it may be reproduced ortransmitted in any way as part of any commercialenterprise without the prior written permission of theDepartment of Education and Science.THIS PUBLICATION IS NOT AVAILABLE FORSALE OR RESALE.

GENDER AND SCIENCEDR SHEELAGH DRUDYPhysics and Chemistry to human well-being. It isalso important to improve women’s capacity tocontrol nature and to appreciate the beauty ofPhysics and Chemistry.IntroductionThe Department of Education introduced thescheme of Intervention Projects in Physics andChemistry in the 1980s. It formed part of theDepartment’s programme for Equality ofOpportunity for Girls in Education, and it arose fromthe observation that, though half the population isfemale, the majority of scientists and engineers aremale. In particular, it was a response to a concern inmany quarters that females were very underrepresented among Leaving Certificate Physics andChemistry candidates. The lack of representationand participation of females in the physicalsciences, engineering and technology is notconfined to Ireland. For the past two decades it hasbeen a major concern throughout most of theindustrialised world.Just as important is the issue of employment. Thereis no doubt that, in the future, the potential for jobopportunities and careers in the scientific andtechnological areas will increase in significance forwomen, in comparison to the ‘traditional’ areas offemale employment. In so far as women are underrepresented in scientific and technological areas,they are disadvantaged in a labour marketincreasingly characterised by this form ofemployment.Achievement and ParticipationInternational ComparisonsAlthough girls and women are well represented inbiological science, their participation andachievement at all levels of education in Physicsand Chemistry have been the focus of muchresearch. This research has sought not only todescribe and analyse female participation inPhysics and Chemistry but to identify ways ofimproving it.In order to put the issue of female participation inPhysics and Chemistry into context, it is useful toconsider the international trends. Since the 1970s anumber of international comparisons of girls’ andboys’ achievements in science have beenconducted. The earliest of these indicated that boysachieved better than girls in all branches of scienceat ages ten and fourteen, and at pre-university level.Studies also showed that while girls were morelikely to take Biology as a subject, they were a lotless likely than boys to take Physics, Chemistry orHigher Mathematics.It is essential that girls and women orientthemselves to the physical sciences and relatedareas for two principal reasons. Firstly there is thequestion of women’s relationship to the naturalworld. It is vital that women’s and girls’ participationin the physical sciences is improved in order toincrease women’s comprehension of the naturalworld and their appreciation of the contribution ofA recent international comparison focused on theperformance of girls and boys in science at age1

thirteen. This study indicated that in most of the 20countries participating, 13 year old boys performedsignificantly better than girls of that age. Thissignificant gender difference in performance wasobserved in Ireland, as well as in most of the otherparticipating countries. This difference wasobserved in spite of the fact that in Ireland, as in themajority of countries, most students had positiveattitudes to science and agreed with the statementthat ‘science is important for boys and girls aboutequally’.Let us now consider the Irish context. Firstly, weshould remember that relatively little science istaught in schools before this age, so it could besuggested that boys have greater socialisation intoscientific ‘culture’ by early adolescence (forexample, through very gender-differentiated toys,comics and television programmes). In addition, theinternational tests mentioned above relied heavilyon the use of multiple-choice. There is evidence thatthe multiple-choice mode of assessmentdisadvantages girls.grades awarded, boys are generally somewhatmore likely to receive an award in the A categorieson the Higher Level papers. However, a higherproportion of girls than boys receive awards at the Band C levels, so overall a higher proportion of girlsare awarded the three top grades in Physics andChemistry at Higher Level. The same is true atOrdinary Level. Grade Point Average for girls inPhysics and Chemistry is higher for girls than forboys at both Higher and Ordinary levels. Thus, inpublic examinations in Ireland, girls outperform boysin Physics, Chemistry and Junior CertificateScience. There is, therefore, no support for thenotion that girls underachieve in the physicalsciences in Ireland, when results are based onperformance in public examinations.This should not be taken to suggest that there is nolonger a problem in relation to gender and scienceamong Irish school-children. There is still a veryserious problem in relation to differential take-uprates in science.Junior and Leaving Certificates: Participation1Junior and Leaving Certificates: AchievementThe important relationship between mode ofassessment and performance in the sciencesbecomes evident when we examine theperformance of girls in public examinations inIreland. Analysis of recent results from the JuniorCertificate and the Leaving Certificate examinationsreveals some interesting patterns. For example, atJunior Certificate level, of the candidates takingscience, a higher proportion of girls are entered atHigher Level than is the case with boys. A higherproportion of girls than boys receive grades A, B orC. This is also the case at Ordinary Level.At Leaving Certificate level, while fewer girls thanboys are entered for Physics, a higher proportion ofthe girls who do take the subject are entered atHigher Level. Traditionally, Chemistry has also beena male-dominated subject, though to a lesser extentthan Physics. More recently, the numbers of girlstaking the subject has equalled, or even slightlyexceeded, the numbers of boys. However, as forPhysics, a higher proportion of the girls who takethe subject do so at Higher Level. As regards2At Junior Certificate level a lower proportion of girlsthan boys are entered for science. At LeavingCertificate level there are very marked variations inparticipation in science by gender. Indeed, overall,more girls than boys sit for the Leaving Certificate.Biology is the science subject most frequently takenby both boys and girls at Leaving Certificate. Interms of participation rates, though, it ispredominantly a ‘female’ subject since two-thirds ofthe candidates are girls.By contrast, in terms of participation rates, Physicsis still very much a ‘male’ subject. Just under threequarters of the Physics candidates are male. It isworthwhile noting that, although there is a greatdisparity in male and female take-up rates inPhysics, there has been a marked increase in theproportion of females taking Physics since the early1980s. This increase (albeit from a very low base)has been the result of a number of factors - one ofthese is the response of second-level schools(especially girls’ schools) to the findings of a majorsurvey by the ESRI (Sex Roles and Schooling2) inthe early 1980s. This study highlighted theGender and Science

extremely low proportion of girls taking Physics.Another factor is the growing awareness amonggirls of the importance of science for future careers.A further important component in the improvementin the take-up of Physics by girls is the impact of thevarious phases of the Intervention Projects inPhysics and Chemistry. Evaluations of thisprogramme have shown that it has had an importantimpact on the participation levels in Physics andChemistry among girls in the target schools. Thispresent handbook is the most recent example of thework of these worthwhile Intervention Projects.However, while it is important to note the increase inparticipation by girls, it is also a matter of seriousconcern that the imbalance in take-up ratesbetween girls and boys in Physics is still so verygreat.In summary, then, as regards achievement andparticipation in the physical sciences, it wouldappear that girls are capable of the highest levels ofachievement. Indeed in terms of overallperformance rates at Junior Certificate Science andin Leaving Certificate Physics and Chemistry girlsnow outperform boys. However, major problems stillremain in relation to participation rates. While someof the variation in these rates is no doubt due to theattitudes and choices of girls, there is equally nodoubt that they are significantly affected by schoolpolicy, particularly as it relates to the provision of thesubjects and the allocation of pupils to them withinthe school.School PolicyVariations in provision according to schooltypeA survey in the early 1980s indicated a veryconsiderable discrepancy in the provision ofPhysics and Chemistry to girls and boys. Since thenprovision of these subjects has improved, especiallyin girls’ schools. However, the most recent analysisof provision indicates the persistence of theproblem. Although provision for girls is now best insingle-sex schools, girls’ secondary schools areless likely to provide Physics to their pupils than areboys’ secondary schools. In co-educational schoolsgirls are proportionately less likely to be providedwith the subject.Given the differential provision in the various schooltypes, the provision of Physics and Chemistry forgirls has been linked with the debate on coeducation. This is an important debate in an Irishcontext, in the light of the overall decline in pupilnumbers, the resulting school amalgamations andthe decline in the single-sex sector. As indicatedabove, for girls, the best provision in these twosubjects is in girls’ single-sex secondary schools.Provision for girls is less favourable in all othertypes of school. However, it is very important torealise that research has pointed to the closerelationship of take-up of science and social class.Thus the weaker provision in vocational schools andcommunity/comprehensive schools probably reflectstheir higher intake of working-class children ratherthan their co-educational structure. Nevertheless,this explanation, on its own, would not account forthe variation between co-educational and single-sexsecondary schools.ProvisionWhether or not a subject is provided in a school isclearly a matter of policy for that particular school.Obviously, there are constraining factors such asthe availability of teachers with appropriatequalifications. This problem was the principal focusof the Intervention Projects in Physics andChemistry. The efforts made in these Projects havemet with some considerable success. Nevertheless,the variability in provision in Ireland, according toschool type, indicates a very strong element ofpolicy decisions in the provision of Physics andChemistry.Gender and ScienceConcern with the effects of co-education on girls,especially with regard to take-up and performancein maths and science, is not confined to Ireland. Forexample, in Britain, it has been the focus of heateddebate. Some have suggested that girls have morefavourable attitudes to physical science in singlesex schools than in co-educational schools. It mustbe noted that the results on attitudes in Ireland, froma major Irish survey, are directly contrary to this. Inthe United States major controversies have arisenwith the introduction of men to formerly all-women’scolleges. In Australia also the issue is a major policy3

one. There also it has been suggested that thesomewhat contradictory evidence must beassessed bearing in mind the higher ability intake inthe majority of single-sex schools which areacademically selective, and also the different socialclass intakes between types of school. It is notpossible to reach a conclusion here on the relativemerits of co-educational or single-sex schools.However, anywhere there is a lack of provision ofkey subjects such as Physics and Chemistry itshould be a matter of concern to school authorities.AllocationClosely linked to the matter of provision of Physicsand Chemistry is that of the allocation policy of theschool. Research has shown that even whereschools provide these subjects there tend t

Module 4 Environmental Chemistry - Water Module 5 Stoichiometry I Module 6 Alcohols, Aldehydes, Ketones and Carboxylic Acids Module 7 Stoichiometry II Module 8 Atmospheric Chemistry Module 9 Materials Module 10 Some Irish Contributions

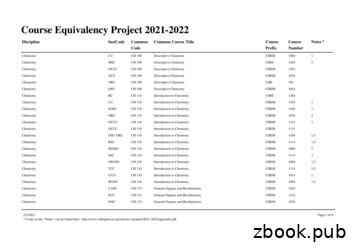

Chemistry ORU CH 210 Organic Chemistry I CHE 211 1,3 Chemistry OSU-OKC CH 210 Organic Chemistry I CHEM 2055 1,3,5 Chemistry OU CH 210 Organic Chemistry I CHEM 3064 1 Chemistry RCC CH 210 Organic Chemistry I CHEM 2115 1,3,5 Chemistry RSC CH 210 Organic Chemistry I CHEM 2103 1,3 Chemistry RSC CH 210 Organic Chemistry I CHEM 2112 1,3

Physical chemistry: Equilibria Physical chemistry: Reaction kinetics Inorganic chemistry: The Periodic Table: chemical periodicity Inorganic chemistry: Group 2 Inorganic chemistry: Group 17 Inorganic chemistry: An introduction to the chemistry of transition elements Inorganic chemistry: Nitrogen and sulfur Organic chemistry: Introductory topics

Marking Scheme Higher Level Design and Communication Graphics Coimisiún na Scrúduithe Stáit State Examinations Commission Leaving Certificate 2013 Marking Scheme Applied Mathematics Higher Level. Note to teachers and students

Accelerated Chemistry I and Accelerated Chemistry Lab I and Accelerated Chemistry II and Accelerated Chemistry Lab II (preferred sequence) CHEM 102 & CHEM 103 & CHEM 104 & CHEM 105 General Chemistry I and General Chemistry Lab I and General Chemistry II and General Chemistry Lab II (with advisor approval) Organic chemistry, select from: 9-10

CHEM 0350 Organic Chemistry 1 CHEM 0360 Organic Chemistry 1 CHEM 0500 Inorganic Chemistry 1 CHEM 1140 Physical Chemistry: Quantum Chemistry 1 1 . Chemistry at Brown equivalent or greater in scope and scale to work the studen

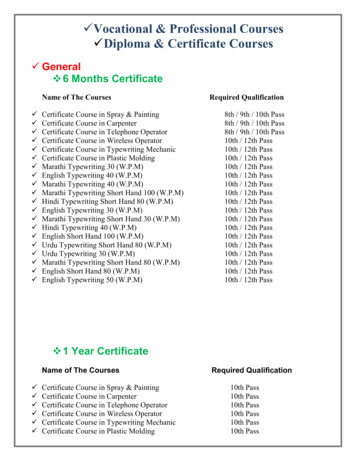

Certificate Course Smart Phone Repairing 10th Pass / Fail Certificate Course in Mobile Repairing 10th Pass / Fail 6 Months Certificate Name of The Courses Required Qualification Certificate Course in Electronics 10th Pass / Fail Certificate Course in Black & White TV Servicing 10th Pass / Fail Certificate Course in Black &With Color TV & DVD 10th Pass / Fail Certificate Course in Color TV .

Prescribed Material for the Leaving Certificate English Examination in 2022 The Department of Education and Skills wishes to inform the management authorities of second-level schools that the attached lists include the prescribed material for the Leaving Certificate English Examination in June 2022.

(a) A certificate for proof of age (Birth certificate or Board certificate). (b) Pass certificate of the qualifying examination. (c) College/ School leaving certificate.[CLC/SLC] (d) Migration certificate (If applicable) (e) 02 recent passport size colour photographs