2018 10 More Women In Tech Del Carpio Guadalupe

More Women in Tech?Evidence from a field experiment addressing social identityLucía Del CarpioMaria GuadalupeINSEADINSEADJuly 2018AbstractThis paper investigates whether social identity considerations -through beliefs and normsdrive occupational choices by women. We implement two randomized field experiments to debias potential applicants to a 5-month software-coding program offered only to low incomewomen in Peru and Mexico. De-biasing women against the idea that women cannot succeed intechnology (through role models, information on returns and female network) doublesapplication rates and changes the self-selection of applicants. By analyzing the self-selectioninduced by the treatment, we find evidence that identity considerations and information onexpected returns act as barriers precluding women from entering the sector, with some highcognitive skill women staying away because of their high identity costs.We are grateful to Roland Bénabou, Sylvain Chassang, Rob Gertner, Bob Gibbons, Zoe Kinias,Danielle Lee, Alexandra Roulet. Moses Shayo and John Van Reenen as well as participants at theCEPR Labour meetings, Economics of Organizations Workshop, Paris-Berkeley OrganizationalEconomics Workshop, MIT Organizational Economics seminar, NBER Organizational Economicsworkshop, LMU Identity workshop, INSEAD, Harvard Kennedy School conference on Women inTech for their helpful comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimer sead.eduMariaGuadalupe:maria.guadalupe@insead.edu1

1. IntroductionIn spite of significant progress in the role of women in society in the last 50 years, animportant gender wage gap persists today. Scholars have shown that a large share ofthat gap can be explained by the different industry and occupational choices men andwomen make. However, the reasons behind those stark differential choices are stillunclear (Blau and Kahn, 2017). In this paper we propose and study “social identity” as akey driver of women’s occupational choices, and in particular, its predominant role inthe persistent occupational gender segregation patterns we observe (see e.g. Bertrand,2011; Goldin, 2014; Bertrand and Duflo, 2016).Starting with at least Roy (1951) economists have explained how people self-selectinto certain occupations/industries as a function of the relative marginal returns totheir skills in different occupations. With that model in mind, women would not selfselect into male dominated industries because their comparative advantage lieselsewhere. However, other things may matter when people may make occupationalchoices that do not follow exclusively their true occupational comparative advantage.For example, scholars have mentioned that the beliefs on expected success givenexisting gender norms, expected discrimination and stereotypes may matter, as well asthe disutility of working in a given environment given one’s gender (eg., AkerlofKranton, 2000; Beaman et al 2012; Goldin 2014; Bordalo et al, 2016a and 2016b;Reuben et al 2014).The fact that social identity and stereotypes are real has long been recognized andshown to be relevant empirically by social psychologists who have designed and testedstrategies to reduce bias and stereotypical thinking (Spencer and Steele, 1999; seesurvey by Paluk and Green 2009). More recently, in a series of lab experiments Coffman(2014) showed that self-stereotyping affects behavior and Bordalo el al (2016b) showthat both overconfidence and stereotyping are important in explaining behavior of menand women (with greater mis-calibration for men). But much of this evidence is in thelab or in the context of academic tests and looks at very short-term outcomes. At theaggregate level Miller et al (2015) show that the prevalence of women in science in acountry is correlated with stereotypes (implicit and explicit). Relatedly, Akerlof and2

Kranton (2000) argue that identity considerations affect a range of individual choicesand Bertrand Kamenica and Pan (2015) show that gender identity norms can explain anumber of important patterns in marriage.The goal of this paper is to bring together, and into the field, the economics of selfselection and the psychology social identity literatures to investigate how important areidentity considerations in the occupational choices women make. Do these biasedbeliefs matter for occupational choices in the real world, can we change them and whatare the economic consequences for the optimal allocation of talent? In particular, wefocus on the choice to enter the technology sector, which in spite of its high growthpotential remains pre- dominantly male and where the male stereotype is very strong(Cheryan et al 2011, 2013).Our framework introduces identity considerations into the Roy (1951)/Borjas(1987) model of self-selection. Women decide whether to enter the technology industry(rather than go to the services sector) as a function of their endowment of “technology”skills, “services” skills and what we will refer to an identity wedge (or bias) of entering asector that is stereotypically male, such as the technology sector. This identity biasaffects the expected returns in technology, and represents a wedge between the actualreturns to skill and the expected returns. This wedge can be driven by a number ofdifferent mechanisms. One class of mechanisms are distorted beliefs that women cannotbe successful in certain industries as implied, for example, by stereotypical thinkingbased on a “representative heuristic” (as in Kahneman and Tversky, 1973 and Bordaloet al 2016a). The wedge can also represent a non-monetary/psychological cost ofworking in an industry where the social norm is very different from one’s socialcategory (as in Akerlof Kranton, 2000).As in the standard Roy model (without identity) self-selection will depend on thecorrelation between the two types of skills and the underlying identity bias relative totheir dispersion. Depending on these correlations and dispersions, we may observepositive or negative self-selection into the technology sector both along the skills andthe identity dimensions: i.e. we may end up with a sample that is on average more orless skilled, and more or less “biased”, with any combination being possible. In addition,once on allows for the presence of an identity wedge, some very high cognitive skill3

women may decide not to enter the industry because they also have a high identity cost.This will distort the optimal allocation of talent across industries.With this framework in mind, we ran two field experiments that aimed to de-biaswomen against the perception that women cannot be successful in the technologysector, increasing their expected returns. In both experiments, we randomly varied therecruitment message to potential applicants to a 5-month “coding” bootcamp andleadership training program, offered only to women from low-income backgrounds by anon-for-profit organization in Latin America.1 We ran the first field experiment in Lima(Peru) where female coders represent only 7% of the occupation. In addition to sendinga control group message with generic information about the program (its goals, careeropportunities, content and requirements), in a treatment message, we added a sectionaiming to correct misperceptions about women’s prospects in a career in technology:we emphasized that firms were actively seeking to recruit women, provided a rolemodel in the form of a successful recent graduate from the program, and highlightedthe fact that the program is creating a network of women in the industry that graduateshave access to. The goal of the message was to change the stereotypical beliefs thatwomen cannot be successful in this industry. Subsequently, applicants to the programwere invited to attend a set of tests and interviews to determine who would be selectedto the training. In those interviews we were able to collect a host of characteristics onthe applicants, in particular those implied by the framework as being important tostudy self-selection: their expected monetary returns of pursuing a career in technologyand of their outside option (a services job), their cognitive skills, and three measures ofimplicit gender bias --two implicit association tests (IAT) including one we createdspecifically to measure how much they identify gender (male/female) and occupationalchoice (technology/services) as well as a survey based measure of identification withtraditional female role). We also collected an array of other demographiccharacteristics, aspirations and games aimed to eliciting time and risk preferences,which allow us to rule out alternative mechanisms for our findings.In this first field experiment (Lima), we find that the de-biasing message wasextremely successful and application rates doubled from 7% to 15%, doubling the1The goal of the organization is to identify high potential women, that because of their backgroundmay not have the option, knowledge or tools to enter the growing technology sector, where it is hardto find the kind of basic coding skills offered in the training.4

applicant pool to the training program. We then analyze the self-selection patterns inthe two groups to assess what are the barriers that are being loosened by the message.We essentially estimate the equilibrium self-selection following an exogenous shock tothe perceived returns to a career in technology. Our results suggest that there isnegative self-selection in average technology skills, average services skills, as well as incognitive skills.We also find positive self-selection on identity costs (i.e. higher bias women apply):on average, women with higher identity cost as measured by the IAT and the traditionalgender role survey measure apply following our de-biasing message, the marginalwoman applying is “more biased”. We argue that this is consistent with a world wherethe identity wedge matters for occupational choice and that this wedge varies acrosswomen.Overall, however, what firms and organizations care about is the right tail of theskills distribution: does treatment increase the pool of qualified women to choose from?We find that even though average cognitive ability is lower in the treated group, the debiasing message significantly increases cognitive and tech specific abilities of the topgroup of applicants, i.e, those that would have been selected for training. Why didhigher cognitive skill women apply even if on average selection is negative? Besides theobvious answer of noise in the distribution of skills or the effect of the experiment, wefind evidence that there are some high skill women that are also high identity wedgewomen that did not apply before treatment and are induced to apply. Finally, we alsomeasured a number of other characteristics and preferences of applicants, which allowus to rule out certain alternative mechanisms of the effects we find.In a second experiment in Mexico City we aimed to disentangle what was theinformation in the first message that the women in Lima responded to. This allows us todirectly test whether it is beliefs about the returns for women, the non-monetarycomponent to being in an environment with fewer women and/or being presented witha role model which mattered most in our first message. It also allows us to rule out thatit is any kind of information provided about women that makes a difference, and alsotease out the relevant components of the identity wedge. Now the control treatmentwas the complete message and in each of three treatments we took out one feature ofthe initial message (returns, network of women and role model) at a time. We found5

that women respond mostly to the presence of a role model. Hearing about the highexpected returns for women in the technology sector and the information that theywould have a network of other women upon graduating are also significant, but to alower extent.A specificity of our setting is that the training is offered only to women, and allapplicants know that. This has the advantage that we can design a message that isspecifically targeted to women without being concerned about negative externalities onmen by providing, for example, a female role model. It therefore allows us to investigatemechanisms that would be harder to investigate as clearly in the presence of men. Thiscomes at the cost that we do not know how men would respond in a setting where theyalso see the de-biasing message, and that we cannot say anything about the role ofidentity for men or other social categories or what kind of message would work as anencouragement to men.This paper contributes to the literature on how women self-select to differentindustries (Goldin, 2014; Flory, Leibbrant and List, 2015) where field experimentalevidence is limited. We test empirically a mechanism that relies on the role of genderidentity and the explicit de-biasing or correction of misperceptions and we are able toanalyze the type self-selection induced by the treatment along different dimensions. Asa result, we also provide a microeconomic evidence on the barriers precluding optimalallocation of talent in the economy studied in Hsieh et al (2013) or Bell et al (2017)We also relate to the literature on socio-cognitive de-biasing under stereotypethreat in social psychology (Steele and Aronson, 1995). It is by now well established inthis literature that disadvantaged groups under-perform under stereotype threat andthe literature has devised successful de-biasing strategies (Good, Aronson, and Inzlicht,2003; Kawakami et al., 2017; Forbes and Schmader, 2010). While this literature focuseson the effect of de-biasing on performance we focus on its effect on self-selection (wecannot assess the effect of de-biasing on performance itself, but it is unlikely to be verybig in our setting given the context of the test and surveys as we discuss later).We also contribute evidence to a very limited literature on the performance effectsof restricting the pool of applicants through expected discrimination or bias. AsBertrand and Duflo (2015) state “the empirical evidence (even non-randomized) on any6

such consequence of discrimination is thin at best”.2 We identify improvements afterde-biasing not only in the number of applicants, but also in the type of applicants andthe number of top applicants available to select from, even though the average quality ofcandidates falls.Finally, our paper is related to the literature showing how the way a position isadvertised can change the applicant pool. Ashraf, Bandiera and Lee (2014) study howcareer incentives affect who selects into public health jobs and, through selection, theirperformance while in service. They find that making career incentives salient attractsmore qualified applicants with stronger career ambitions without displacing pro-socialpreferences. Marinescu and Wolthoff (2013) show that providing information of higherwages attracts more educated and experienced applicants. And Dal Bó et al. (2013)explore two randomized wage offers for civil servant positions, finding that higherwages attract abler applicants as measured by their IQ, personality, and proclivitytoward public sector work. In contrast to these papers we find negative self-selection onaverage, which highlights the fact that an informational treatment is not always apositive intervention and that it is important to take into account the returns of theoutside option, and the correlations between returns, and whether the organization canscreen candidates at a later stage. In other words: the informational treatment maybackfire for the firm designing it depending on the underlying parameters of choicesand beliefs.The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 presents a theoretical framework of selfselection in the presence of an identity wedge; Section 3 presents the context for theexperiment, Section 4 describes the two interventions; Sections 5 and 6 discuss theresults from our two experiments and Section 7 concludes.2. Framework: Self-Selection into an industryThis section develops a simple theoretical framework to illustrate how changing theinformation provided on a career/an industry--as we will do in the field experiment-affects which applicants self-select into that career. We start from a standard2Ahern and Dittmar (2012) and Matsa and Miller (2013) find negative consequences on profitability andstock prices of the Norway 2006 law mandating a gender quota in corporate board seats and findnegative consequences on profitability and stock prices.7

Roy/Borjas model (Roy, 1951; Borjas 1987) adapted to our setting and add an identitycomponent as a potential driver of the decision to enter an industry in addition to therelative return to skills in the two industries, as in the classic model.Women decide between applying or not applying to the training program, i.e.,whether to attempt a career in the technology sector. Each woman is endowed with agiven level of skills that are useful in the technology sector T and skills that are useful inthe services sector S. Assume for now that identity does not matter: Total returns inServices and in Tech are given by W0 P0 S and W1 P1T , respectively, where P0 and P1are the returns to skill (e.g. wage per unit of skill) in each sector. If we log linearize andassume log normality: ln 𝑊 𝑝 𝑠 and lnW1 p1 t where lnS s N(0, σ s2 ) and lnT t N(0, σ t2 ). The probability that a woman applies to the technology sector is:Pr 𝐴𝑝𝑝𝑙𝑦 Pr p1 t p0 s Pr[D p0 p1p p ] 1 Φ[ 0 1 ]σDσDσDWhere D t –s and Φ is the CDF of a standard normal. Pr (Apply) is increasing in p1and decreasing in p0 , such that as expected returns in technology increase, morewomen will apply to Tech. This allows us to study how the selection of women (theaverage expected level of t) that apply will change with a change in returns totechnology skill. Borjas (1987) shows that E(T Apply) ρtDσ t λ (p0 p1)σDwhereρtD σ tD / (σ Dσ t ) is the coefficient of correlation between t and D, and λ (z) is theinverse mills ratio, with λ ' 0 . Therefore:dE(T Apply) σ t2 σ dp1σDGivenstd λ (z).dp1d λ (z) 0 and σ v 0 the sign of the selection will depend on the sign ofdp1σ t2 σ st . In particular, if ρts ρts σtdE(T Apply) 0 and selection is positive, andσsdp1σtdE(T Apply) 0 selection is negative and the average Tech skills ofσsdp18

applicants decreases in the expected returns to Tech skills. Similarly, we can sign theselection for Services skills, S. If ρts σsdE(S Apply)σdE(S Apply) 0; ρts s 0σtdp1σtdp1Finally, we have that in terms of relative skills D, the selection is always ��(𝑧) 𝜎6 0𝑑𝑝4𝑑𝑝4Now we depart from the classic model to introduce the concept of identity to thebasic framework. Women form an expectation of their returns as a function of their skillendowments in each industry and decide whether to apply to one sector or the other.We propose that this expectation may be affected by a social identity component. Wewill call this an identity bias or identity wedge, that alters the total expected returnsrelative to the skill endowment and could be reflecting different features in the realworld. This bias may arise from beliefs held by women on the effective returns to theirskills. For example, a belief that women cannot succeed in the technology industrybecause there is discrimination and their skills are not valued. It could also reflect thefact that people form a stereotype of who can succeed in the industry based on existingrepresented models in the industry, which include few women (Bordalo et al 2016a). Sothe more strongly the stereotype is held, the higher the wedge and the lower theexpected returns. It could also reflect, along the lines of the identity cost proposed byAkerlof and Kranton (2000) the perceived cost for a woman of operating in theindustry, for example if women want to work with other women and the sector ispredominantly male, their

survey by Paluk and Green 2009). More recently, in a series of lab experiments Coffman (2014) showed that self-stereotyping affects behavior and Bordalo el al (2016b) show that both overconfidence and stereotyping are important in explaining behavior of men and women (with greater mis-calibration for men). But much of this evidence is in the

42 wushu taolu changquan men women nanquan men women taijiquan men women taijijlan men women daoshu men gunshu men nangun men jianshu women qiangshu women nandao women sanda 52 kg women 56 kg men 60 kg men women 65 kg men 70 kg men 43 yatching s:x men women laser men laser radiall women 1470 men women 49er men 49er fxx women rs:one mixed

Test Name Score Report Date March 5, 2018 thru April 1, 2018 April 20, 2018 April 2, 2018 thru April 29, 2018 May 18, 2018 April 30, 2018 thru May 27, 2018 June 15, 2018 May 28, 2018 thru June 24, 2018 July 13, 2018 June 25, 2018 thru July 22, 2018 August 10, 2018 July 23, 2018 thru August 19, 2018 September 7, 2018 August 20, 2018 thru September 1

unfair portrayal of women and men in advertising. Although recent studies have shown that the portrayal of women in advertisements has gotten a lot better recent analyses have still shown that television media portrays women the same way in the past. These stations include ones such as prime time and MTV which air commercials that still depictFile Size: 1MBPage Count: 20Explore furtherChanging portrayal of women in advertisingbestmediainfo.comChanging the Portrayal of Women in Advertising - NYWICInywici.orgSix stereotypes of women in advertising - Campaignwww.campaignlive.co.ukHow Women Are Portrayed in Media: Do You See Progress .www.huffpost.comRecommended to you b

Women SME Entrepreneurs UN WOMEN CHINA Beijing, April, 2022 UN Women is the UN organization dedicated to gender equality and the empowerment of women. A global champion for women and girls, UN Women was established to accelerate progress on meeting their needs worldwide. UN Women supports UN Member States as they set global standards for

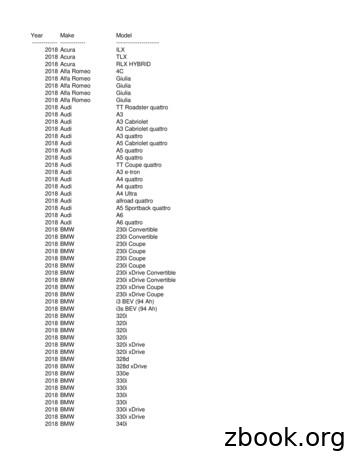

Year Make Model----- ----- -----2018 Acura ILX 2018 Acura TLX 2018 Acura RLX HYBRID 2018 Alfa Romeo 4C 2018 Alfa Romeo Giulia 2018 Alfa Romeo Giulia 2018 Alfa Romeo Giulia 2018 Alfa Romeo Giulia 2018 Audi TT Roadster quattro 2018 Audi A3 2018 Audi A3 Cabriolet 2018 Audi A3 Cabriolet quattro 2018 Audi A3 quattro

IV. Consumer Price Index Numbers (General) for Industrial Workers ( Base 2001 100 ) Year 2018 State Sr. No. Centre Jan., 2018 Feb., 2018 Mar., 2018 Apr 2018 May 2018 June 2018 July 2018 Aug 2018 Sep 2018 Oct 2018 Nov 2018 Dec 2018 TEZPUR

women’s archives, a tradition that–not at all coin-cidentally–began in the 1890s and early 1900s around the time the Women’s College was found-ed. For there is a connection between the pursuit of women’s education and the documentation of women’s past activities. The women and men who insisted

contents 2 3 executive summary 5 women, poverty and natural resource management 5 poverty 7 land tenure 9 education 10 health 17 engage women, drive change 17 empowering women to manage natural resources 21 engaging women in natural resource management is good for women 23 engaging women in natural resource management is good for