Professional Writing In SPeech-language Pathology And .

Professional Writing inSpeech-Language Pathologyand AudiologyThird Edition

Professional Writing inSpeech-Language Pathologyand AudiologyThird EditionRobert Goldfarb, PhDYula C. Serpanos, PhD

5521 Ruffin RoadSan Diego, CA 92123email: information@pluralpublishing.comwebsite: http://www.pluralpublishing.comCopyright 2020 by Plural Publishing, Inc.Typeset in 11/13 Garamond by Flanagan’s Publishing Services, Inc.Printed in the United States of America by McNaughton & Gunn, Inc.All rights, including that of translation, reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,recording, or otherwise, including photocopying, recording, taping, web distribution, or information storage and retrieval systems without the prior written consent of the publisher.For permission to use material from this text, contact us byTelephone: (866) 758-7251Fax: (888) 758-7255email: permissions@pluralpublishing.comEvery attempt has been made to contact the copyright holders for material originally printed inanother source. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will gladly make thenecessary arrangements at the first opportunity.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataNames: Goldfarb, Robert (Robert M.), author. Serpanos, Yula Cherpelis,author.Title: Professional writing in speech-language pathology and audiology /Robert Goldfarb, Yula C. Serpanos.Description: Third edition. San Diego, CA : Plural, [2020] Includesbibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2018028839 ISBN 9781635500134 (alk. paper) ISBN1635500133 (alk. paper)Subjects: MESH: Medical Writing Speech-Language Pathology AudiologyClassification: LCC RC423 NLM WZ 345 DDC 808/.066616--dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018028839

ContentsIntroductionxi1Getting StartedBeginnings of Speech-Language PathologyBeginnings of AudiologyAbout the Deaf Community and Hearing ImpairmentCurrent IssuesEnglish MechanicsParts of SpeechGrammatical MorphemesPhrase Structure RulesExercisesReferences2Writing RulesErrors in FormWriting Form (punctuation, spelling, grammatical morphemes)PunctuationSpellingGrammatical Morphemes and Common ConfusionsWriting Content and Composition (Semantics, Sentence Structure)ExercisesFinal d WritingWriting a Professional Paper/Journal ArticleA. TitleB. AbstractC. IntroductionD. MethodsE. ResultsF. Discussion and ConclusionG. 115115116137v1123334781432

vi Professional Writing in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology4Ethics of Professional WritingThe ASHA Code of EthicsPrinciple of Ethics IPrinciple of Ethics IIPrinciple of Ethics IIIPrinciple of Ethics IVHealth Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)The Institutional Review BoardThe Belmont ReportNational Institutes of Health (NIH) Training CourseConclusionExercisesReferencesAppendix 4–A. Sample Institutional Review Board Research Review erencing ResourcesHistory of the LibraryCollectionsBooksScholarly JournalsAudiovisual MaterialsMicroformsServicesThe Organization of Information: Catalogs and DatabasesConducting a SearchInterlibrary Loans/Reciprocal Library PrivilegesReference ServicesReserve ItemsCourse PacksCopyright MaterialPlagiarismCiting References From Print Books and JournalsWriting References in APA Style: Review of Selected APA-Style (2010)Reference List and In-Text Citation 165166168168169169169170170170Internet ResourcesWhat is the Internet?Syntax, Semantics, and JargonInternet Glossary: An Exercise in FutilityUses and AbusesCiting References from the InternetElectronic ArticleElectronic Article (where the format is modified from the print version)Specific Internet DocumentArticle in an Internet-Only JournalEvaluating Internet Sources for Professional Writing2012012022022042052062072072072076175199

ContentsviiPeer-Reviewed JournalsPeer-Review ProcessWhich Internet Resources Should We Use (And Which Should We Avoid)?Do UseDon’t UseShould We Use These Internet Resources? Why or Why Not?Final 7Writing for Oral PresentationPreparing the Oral PresentationDeveloping the SpeechOutlining the PresentationDelivering the Oral PresentationComputer-Generated PresentationsCreating Computer-Generated PresentationsFactors in Effective Speech DeliveryTips for Delivering the SpeechSample Computer-Generated PresentationProfessional PresentationsI. The Poster PresentationII. The Platform PresentationIII. The Short 232242262272282282302448The Diagnostic ReportDiagnostic LabelingThreats to Accurate DiagnosisRules for DiagnosisRule 1Rule 2Rule 3Rule 4Rule 5Writing the Diagnostic ReportThe Logic of Report WritingThe Diagnostic Report FormatGuidelines for Writing Diagnostic Reports in Speech-Language Pathologyand AudiologyWriting AspectsFormatSections of the Diagnostic ReportReport DraftsWriting the HistoryDiagnostic Report Format — Speech and LanguageReferral 252252253253254254254

viii Professional Writing in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology9Background InformationAssessment InformationClinical ImpressionsRecommendationsDiagnostic Protocol Worksheet — Speech and LanguageReferral InformationBackground InformationAssessment InformationSample of Diagnostic Report Writing in Speech-Language PathologySpeech-Language Evaluation Report — OriginalSpeech-Language Evaluation Report — Revised VersionDiagnostic Report Format — AudiologyHistoryAssessment InformationClinical ImpressionsRecommendationsDiagnostic Protocol Worksheet — AudiologyHistoryAssessment InformationSample of Diagnostic Report Writing in AudiologyAudiologic Evaluation Report — OriginalAudiology Evaluation Report 293Clinical Goals, Reports, and ReferralsInformed Consent and PermissionJustificationInformed Consent FormPermission FormWriting Clinical ObservationsWriting Goals for TherapyTypes of Professional ReportsI. Treatment (Therapy Session) Format Plan in Speech-Language PathologyII. Progress ReportGuidelines for Writing Progress Reports in Speech-Language PathologyProgress Report: Writing Style WorksheetEdited Progress Report in Speech-Language PathologyIII. Audiogram Form ReportIV. Medical Chart Logs/ReportsProfessional CorrespondenceProfessional Referrals/Sending ReportsSample Authorization of Release of Information FormCorrespondence Via Electronic MediaLetters to ProfessionalsCover Letters for Professional ReportsLetters as 300302302303304305305308308309309310310311313359

Contentsix10IndexWriting for Professional AdvancementWriting for Professional cationCertifications/LicensesProfessional ExperienceAwards/HonorsPublicationsProfessional PresentationsResearchProfessional Affiliations/ActivitiesSkillsReferencesSample Student Resume FormatII. Cover Letters for ResumesResume Cover Letter FormatSample Resume Cover LetterIII. PortfoliosSample Portfolio Checklist of Clinical Work in AudiologySample Portfolio Checklist of Clinical Work in Speech-Language Pathology (AdelphiUniversity Codes)IV. Professional Correspondence Via Electronic MediaSections of Formal CorrespondenceSample E-Mail CorrespondenceMultiple-Choice TestsThe StemThe OptionsGraduate Record Examination (GRE )Praxis Examinations in Speech-Language Pathology and 378378378378379379379382390391

Introduction“If you didn’t document it, you didn’t do it.” Competent professional writing is a necessity, not aluxury. Third-party payers, such as insurance companies, may deny payment if the documentationfor professional services is incorrect or incomplete. Medical chart notes, diagnostic evaluations,progress reports, and discharge summaries are alllegal documents that may be used in court. TheCode of Ethics of the American Speech-LanguageHearing Association (ASHA, 2016) states that individuals shall provide all services competently, andthat includes documentation of services rendered.The authors were motivated to write thepresent book to address writing problems exhibited by undergraduate and graduate students incommunication sciences and disorders (CSD), laxdocumentation by clinicians, and general slovenliness in professional discourse. Since the secondedition was published in 2014, we have figuratively blown our tops at students’ overuse of literally in conversation, although this trend has not(yet) infected their professional writing. We continue to remind students that they are off base ifthey write based off of instead of based on. Lastly,we understand the reasons for accepting a singular form of they in spoken discourse, but rejectits use in professional writing. The Third Editionincludes expanded exercises in all sections, inresponse to reviewers who used the second edition and requested more practice opportunities.We include a more accessible website insteadof a bundled CD for additional materials. Wealso responded to feedback from students whoenrolled in a Professional Writing Boot Camp atAdelphi University that led to some changes andadjustments in the present volume. Guidelines forinstituting writing boot camps at other collegesand universities appear in the website. In addition, RG field-tested portions of the second edi-tion as a Fulbright Senior Specialist in Linguisticsin Bogota, Colombia. The graduate TEFL studentsattended research methods and academic writinglectures in English, and provided valuable feedback regarding both English and Spanish materials provided in the courses.In the past few years, we have had our concerns about professional writing shared by sitevisitors from the National Council for Accreditationof Teacher Education programs (NCATE). Withinour own disciplines, the Council of AcademicAccreditation (CAA) evaluators of our graduateprogram in speech-language pathology, the CAAsite visitors of our consortial doctor of audiologyprogram, and the CAA teams that joined RG onsite visits to other colleges and universities echoedthe need for improvement in professional writing.In all cases, we were assured that the decline inprofessional writing was a national concern.At a recent meeting of the Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences andDisorders, we were eager to learn how otherCSD programs assessed professional writing. Welearned that while some programs denied admission to students applying for matriculation in graduate degree programs based on poor professionalwriting, other programs ignored professional writing, and one program director was honest enoughto admit, unofficially, that writing requirementswere “dumbed down” to give the program a perceived competitive advantage in recruitment. Allprograms welcomed a resource for professionalwriting that was comprehensive and scholarly.In our research for the present book, we havediscovered some fine style manuals for researchreports and professional writing, as well as workbooks focusing on drill work. In this volume, wehope to provide reasons and explanations for thesuggestions we make, and to support our claimsxi

xii Professional Writing in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiologywith relevant professional citations. We do not thinkour students need to attend “remedial graduateschool,” nor do we doubt that every CSD studentand professional practitioner can learn to writecompetently. We also think that learning to bea better professional writer does not have tobe drudgery and have attempted to leaven ourinstruction with humor and stories.Chapter 1 has some material that is new tothe third edition, and includes an overview of English mechanics underlying syntax. In addition toa review of parts of speech, the chapter includesinformation about sentence structure, syntacticdevelopment, and disorders of syntax.In Chapter 2, we describe language as ourfavorite toy, where even punctuation can be funny.Other topics include the alphabet soup of abbreviations that we use professionally; the mutabilityof language, especially among young adult users;and such thorny issues as gender neutrality andcultural differences. There are examples of correct and incorrect forms of usage throughout thechapter, as well as exercises at the end that reviewsome of the themes. We have included many exercises and worksheets to address common errorsin written expression; a list of common abbreviations that we use in professional writing; and haveadded to the website sections on strong language,“Mondegreens,” and a game to use Shakespeare’sinsults to improve vocabulary. When students askwhy there is so much professional jargon in ourdisciplines, we sometimes give the flip answer,“So you can charge more.” The reality is that everytrade and professional group uses jargon, whetherit’s “Adam and Eve on a raft” (two sunny-side upeggs on toast) in a local diner, or the contents ofa legal document.The focus of Chapter 3, evidence-based writing, is to provide the reader with strategies toanswer the “why” questions about professionalwriting. We include annotated samples of students’evidence-based writing. We take you through thestages of writing a journal article. Our goal formost readers is to help them become educatedconsumers of research, not necessarily producersof research. We would also like to foster a cognitive shift away from the educational model inpreparing therapy plans and reporting treatmentto one where the clinician is testing hypotheses.After all, if you are following a curriculum, youmay continue with it even if it doesn’t seem to beworking, whereas, if your hypothesis is falsified,you can begin testing another one.As noted above, the ASHA Code of Ethics(revised in 2016) requires that we discharge ourduties honorably and document our servicesappropriately. In Chapter 4, we review the Principles of Ethics that relate to professional writing,the constraints imposed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996(HIPAA), and the guidelines for writing a successful research proposal to an Institutional ReviewBoard. Since 2000, anyone seeking federal grantsupport is required to have a current certificateindicating a passing grade (currently 80%) onthe web-based training program on the protection of human research participants administeredthrough the National Institutes of Health. Studentsand professionals in communication sciences anddisorders (CSD) are obliged to learn ASHA’s codeof ethics. There are many other websites relatedto ethics, and we provide the links for instructionabout ethics in areas related to CSD.Using library resources, discussed in Chapter 5, begins with a history of the library, followedby a discussion of collections and services. Thoseof us who enjoy the musty smell of the stackscan still indulge in this activity, but we also needto know how to conduct electronic searches. Asinstructors often use a course pack to supplementor substitute for a traditional textbook, we considered it worth noting. We also include sections oncopyright and plagiarism. We would like a fieldtrip to a college or university library to be partof the requirements for Chapter 5. Although wecan access most of what the library has to offerthrough a desktop computer at home, we find the“bricks-and-mortar” experience of being in thebuilding to be stimulating and informative. Thereis an extended set of exercises in correct use ofAPA 2010 style for referencing.As we say in Chapter 6, on using Internetresources, welcome to the new way of doing business, meeting your life partner, succeeding in academia, and conducting your clinical practice. Thesyntax, semantics, and jargon associated with the

IntroductionxiiiInternet today may appear out of date and evenquaint by the time this chapter gets to the reader,but the section on uses and abuses of the Internetshould remain relevant. We continue the discussion about research-based writing in this chapter.We recommend Internet resources to use, as wellas those to avoid; explain the peer-review processfor both print and electronic media; and recommend sites and strategies for database searches.We have not seen a section on writing for oralpresentation, which is covered in Chapter 7 inthe current volume, in other professional writingbooks. Preparing an oral presentation is a topic ofimportance in basic books on rhetoric and publicaddress, but we include it here to show how todevelop a speech and to outline the presentation.In delivering the oral presentation, particularlyone that includes computer-generated visual aids,we differentiate what should appear on the slidescompared to what should be included in effectivespeech delivery. An oral report in class, a demonstration of a diagnostic test in clinical practicum, and a short course at ASHA are all based onwritten preparation. As the poster presentationis popular as an assignment for demonstratingevidenced-based practice in university clinics,as well as for disseminating research findings atprofessional conventions, we devote considerable attention to preparing a poster, and includeexamples on the accompanying website.The diagnostic report, Chapter 8, is one of thelengthier sections of the book, divided into twoparts. The first part specifies and describes fiverules for diagnosis. For example, we address thesecond rule, Be an Educated Consumer of Tests andMeasures, to all audiologists and speech-languagepathologists who must understand research methodology even if they do not actively produceresearch. The guidelines for writing diagnosticreports in speech-language pathology and audiology, in the second part of the chapter, includespecific instructions and examples for diagnosticprotocols and report formats. Exercises start withthe building block of phonetic transcription, whichincludes solving and writing a crossword puzzle inphonetics. Following that are original and editeddiagnostic reports in speech-language pathologyand audiology, and exercises for editing reports.Chapter 9, clinical goals, reports and referrals, includes templates and samples of a treatment plan, progress report, and chart note, aswell as forms of professional correspondence. Wereview issues in clinical writing related to terminology, ethics, and software. Exercises includewriting cover letters for professional reports, writing letters as reports, completing an audiometricprofile, and entering log notes in medical charts.We take you through the step-by-step process ofevaluating background information, includingtest results, and making recommendations.We end the book with an updated Chapter 10 on writing for professional advancement,because the format and number of questionshave changed on our national examinations. Thegraduating student seeking a clinical fellowship,and the seasoned professional moving forwardin a rewarding career, need strategies for developing professional documents. The chapter concludes with an analysis of multiple-choice tests,those used in the Praxis II exam as well as thoseprepared by course instructors. Exercises includedeveloping a personal resume, preparing a professional cover letter, and developing a professional portfolio.In recognizing the many people who helpedus with this project, we want to pay a special tribute to the late Dr. Sadanand Singh, the founderof Plural Publishing, Inc. Singh (there is no disrespect intended; that is how he asked many of usto address him) also indicated that, although hecould not read all manuscripts submitted or published, he did read our earlier one and enjoyedit very much. Angie Singh currently carries thetorch at Plural, and she has been a wonderfulsource of support for us.We are grateful for the assistance of Professor Suzy Lederer and Ms. Dawn Cotter-Jenkins atAdelphi University in providing some of the clinicforms used in this book. Professor Susan Behrens, a linguistics professor in the CSD Department at Marymount Manhattan College, spent agreat deal of time with us to make sure that allappropriate grammatical rules were included inthe third edition, and that our examples in theexercises were clear and appropriate. Our editorsat Plural Publishing, Inc. — Kalie Koscielak and

xiv Professional Writing in Speech-Language Pathology and AudiologyValerie Johns — have provided encouragement,cheerleading, and welcome deadlines throughout the writing project. Terry Gozdziewski fieldtested the earlier editions in her writing classesand offered valuable suggestions. Our graduateresearch assistant, Yulia Kovalenko, painstakingly checked all chapters for clarity, ease of flow,and accuracy. Another graduate student, MonicaFernandes, corrected the Spanish version of thebook that Google Translate yielded to produce acoherent Spanish version of the chapters used inBogota. Our students’ excellent work has inspiredus, and their not-quite-so-excellent writing hasmotivated us, in preparing composite examplesof diagnostic and treatment reports.To Shelley and Elizabeth Goldfarb, MattSimon and Tessera Rose; and to Andreas, Marie,and Ariana Serpanos, Luke Hardcastle, and MarkMcClean — we love you madly. To Shelley and toElizabeth V. Goldfarb, Matthew D. Simon, and to. . . (as written).We invite readers to send comments and suggestions to us by email at:Goldfarb2@adelphi.eduSerpanos@adelphi.edu

To our daughters and their husbands.

1Getting StartedLanguage is our favorite toy. We encourage you toplay with it, develop your own skill set, and havefun inventing and reinventing your unique useof it. At the same time, we want you to developa consistently excellent professional writing (andspeaking) style, using conventions universallyunderstood by speech-language pathologists andaudiologists. The professional and personal language you use will be quite different from whatwe wrote and said as undergraduate and graduate students. Emerging technology, especially inaudiology, but also in areas of speech-languagepathology such as alternative and augmentativecommunication, has resulted in a new and richervocabulary, with terms borrowed from computerscience, engineering, and medicine.Nowhere is the flux of language more evident than in the words used by young adults torepresent something or someone in exceedinglypositive terms. These have evolved from “the cat’spajamas” to “groovy,” “far out,” and “def.” The lastterm gives us an opportunity to examine what isclaimed here to be a misunderstanding based onvernacular English. The term def does not referto hearing loss; rather, as it originated in innercities, it refers to death in an ironic way. Thereis a phonological rule in African American Vernacular English (AAVE) where the sound madeby the voiceless th (theta), when appearing aftera vowel, is pronounced as the sound made by theletter f. We write the rule as follows: postvocalic/θ/ /f/. This rule, as legitimate as any other inphonology, represents the accepted practice ofa large linguistic community. It is important tonote the difference between vernacular Englishand language disorder, as Jones, Obler, Gitter-man, and Goldfarb (2002) indicate in a comparison of AAVE to agrammatism in aphasia. We cansee now that the use of def actually correspondsto a phrase — the livin’ end — used as a superlativeseveral generations ago, for what is the end of life(the livin’ end), but def?Finally, as you play with your new languagetoy, resist the urge to turn nouns into verbs orverbs into nouns. Former President George W.Bush caused himself political harm by creatinga noun from the verb to decide. Calling himself“the decider” resulted in a cascade of politicalcartoons, usually with a superhero in cape andtights (and the President’s face) and a capital Demblazoned on his chest. The President wouldhave been much better served by using the termcommander-in-chief or even the boss. Similarly,creating a verb form of clinician is not the mostapt way of expressing the notion that a speechlanguage pathologist or audiologist should bewell rounded, as in, “To be a good clinician, youshould cliniche with all types of cases.”Beginnings ofSpeech-Language PathologyThis section is devoted to the beginnings of thefield of speech-language pathology as well asthe professional titles we use when referringto our colleagues and ourselves. The origins ofspeech-language pathology are usually tracedto physicians in German-speaking countries inEurope during the early 1900s and shortly thereafter to the University of Iowa in the United States1

2 Professional Writing in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology(Goldfarb, 1985). In 1918 the University of Viennaappointed Emil Froeschels to serve as chief physician and speech pathologist (emphasis added)in the department of speech and voice disordersat the Central Hospital in Vienna. Together withHugo Stern, his counterpart in the phoniatricsdepartment, Froeschels convoked a meeting ofwhat he dubbed the First International Congressof Logopedics and Phoniatrics. That meeting, heldon July 3 to 5, 1924, at the Vienna Institute ofPhysiology, attracted some 65 specialists from thefields of laryngology, psychology, and pedagogical subjects. All but two of the participants wereGerman-speaking Central Europeans.At roughly the same time, across the seas inthe United States, efforts were begun to developthe study and treatment of speech and hearingproblems as a nonmedical field of professionalspecialization. Carl Emil Seashore, a psychologistand Dean of the Graduate College at the University of Iowa, selected a promising graduate student to develop a new program. This student, LeeEdward Travis, was probably the first individualin the world to be trained at the PhD level towork experimentally and clinically with speechand hearing disorders. His preparation involvedstudy in the departments of psychology, speech,physics, psychiatry, neurology, and otolaryngology. In 1927, Travis became the first director ofthe University of Iowa Speech Clinic.At the present time the International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics (IALP) convenes a congress every three years. The AmericanSpeech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA),which is affiliated with IALP, presently lists morethan 190,000 members (ASHA, 2018a). The professional titles of logopedist and phoniatrist havenot been adopted in the United States. Thesetitles and others are used primarily in Europe. Forinstance, the professional title of orthophoniste isused in France, as noted in Jean-Dominique Bauby’s 1997 account of his brainstem stroke, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. If they were used in theUnited States, the first author of this book wouldhave to be called a logogerist, because he workswith the elderly. Instead, in the United States,there has been a shift from identifying our practice as speech correctionists to speech-languagepathologists, a shift that is traceable to the end ofWorld War II. When injured soldiers, sailors, andmarines returned to Veterans Administration Hospitals (now VA Medical Centers) with speech andlanguage disorders secondary to head trauma, theattending psychiatrists and psychologists foundthey were not equipped to deal with these communication impairments. Some psychologists,notably Jon Eisenson, acquired expertise in bothpsychology and speech-language pathology, butthe American Speech and Hearing Association (asit was called then) began emphasizing languagein the scope of practice of its members. The addition of Language to the title came in the 1970s,when Norma Rees was president of ASHA (whichpreferred to keep its acronym rather than changing it to the unwieldy ASLHA).Beginnings of AudiologyAudiology emerged as a distinct profession in theUnited States during World War II, where noiseexposure to the modern weapons of the timescreated the necessity of diagnostic and rehabilitative services for many returning military personnel. At the time, audiologic services wereadministered by professionals in related areas,mostly otologists and speech-language pathologists, and included psychologists and teachers ofthe deaf, who ultimately became the first audiologists. The term audiology given to the new profession meaning “the study of (logos: Gr.; audire: L.)hearing” (Martin & Clark, 2012, p. 4) is attributedto otolaryngologist Norton Canfield and speechlanguage pathologist Raymond Carhart.Robert West, a speech-language pathologist,is credited with expanding the discipline ofspeech correction to include hearing services(Bess & Humes, 2003). Audiologic services wereofficially recognized within the profession’s purview by ASHA (then known as the AmericanAcademy of Speech Correction) in 1947, wherethe organization voted to include the term hearing in the association’s title (Paden, 1975). Atpresent, ASHA is the largest organization representing audiologists, with over 12,000 certified

1. Getting Started 3members, a number that is substantially lowerthan the membership of over 165,000 certifiedspeech-language pathologists also represented byASHA (ASHA, 2018b).A movement to create an independent organization for audiologists resulted in the formationof the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) in1988 with a mission to “promote quality hearingand balance care by advancing the profession ofaudiology through leadership, advocacy, education, public awareness and support of research”(AAA, 2018). With over 12,000 members, theAAA is currently the largest independent professional organization operated specifically by andfor audiologists. Like ASHA, the AAA offers clinical certification to its qualified memb

sample student resume format 364 ii. cover letters for resumes 364 resume cover letter format 367 sample resume cover letter 367 iii .Portfolios 368 sample Portfolio checklist of clinical Work in audiology 368 sample Portfolio checklist of clinical Work

The purpose of the East Tennessee State University Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic is twofold: first, to provide training to students majoring in speech-language pathology and audiology; and second, to provide professional services to members of the general public and university community with speech, language, and/or hearing problems.

Speech-Language Pathology Assistant (3003)- 130.00 Audiology Assistant (3004)- 130.00 Application for Speech-Language Pathology or Audiology Assistant Certification Board of Speech-Language Pathology & Audiology P.O. Box 6330 Tallahassee, FL 32314-6330 Fax: (850) 245-4161 Email: info@floridasspeechaudiology.gov Do Not Write in this Space

with an interest in speech.” But anyone can do that today: Parents, teachers, teach aids, speech aids, grandmothers, nannies, babysitters. Anyone can provide lessons in speech improvement. Speech-Language Pathology: The speech-language pathologist’s job is to go much deeper than the process of simple speech improvement.

speech 1 Part 2 – Speech Therapy Speech Therapy Page updated: August 2020 This section contains information about speech therapy services and program coverage (California Code of Regulations [CCR], Title 22, Section 51309). For additional help, refer to the speech therapy billing example section in the appropriate Part 2 manual. Program Coverage

speech or audio processing system that accomplishes a simple or even a complex task—e.g., pitch detection, voiced-unvoiced detection, speech/silence classification, speech synthesis, speech recognition, speaker recognition, helium speech restoration, speech coding, MP3 audio coding, etc. Every student is also required to make a 10-minute

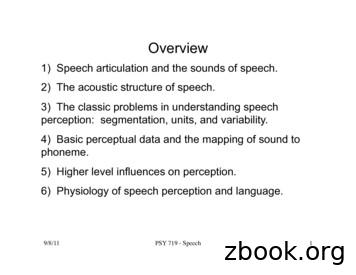

9/8/11! PSY 719 - Speech! 1! Overview 1) Speech articulation and the sounds of speech. 2) The acoustic structure of speech. 3) The classic problems in understanding speech perception: segmentation, units, and variability. 4) Basic perceptual data and the mapping of sound to phoneme. 5) Higher level influences on perception.

1 11/16/11 1 Speech Perception Chapter 13 Review session Thursday 11/17 5:30-6:30pm S249 11/16/11 2 Outline Speech stimulus / Acoustic signal Relationship between stimulus & perception Stimulus dimensions of speech perception Cognitive dimensions of speech perception Speech perception & the brain 11/16/11 3 Speech stimulus

Speech Enhancement Speech Recognition Speech UI Dialog 10s of 1000 hr speech 10s of 1,000 hr noise 10s of 1000 RIR NEVER TRAIN ON THE SAME DATA TWICE Massive . Spectral Subtraction: Waveforms. Deep Neural Networks for Speech Enhancement Direct Indirect Conventional Emulation Mirsamadi, Seyedmahdad, and Ivan Tashev. "Causal Speech