This Page Intentionally Left Blank. - Legal Information Institute

This page intentionally left blank.

Introduction toBASIC LEGALCITATIONPETER W. MARTIN

2020 Peter W. Martin

Table of Contents PREFACE§ 1-000. BASIC LEGAL CITATION: WHAT AND WHY?o § 1-100. Introductiono § 1-200. Purposes of Legal Citationo § 1-300. Types of Citation Principleso § 1-400. Levels of Masteryo § 1-500. Citation in Transitiono § 1-600. Who Sets Citation Norms§ 2-000. HOW TO CITE .o § 2-100. Electronic Sources § 2-110. Electronic Sources – Core Elements § 2-115. Electronic Sources – Points of Difference in Citation Practice § 2-120. Electronic Sources – Variants and Special Caseso § 2-200. Judicial Opinions § 2-210. Case Citations – Most Common Form § 2-215. Case Citations – Points of Difference in Citation Practice § 2-220. Case Citations – Variants and Special Cases § 2-225. Case Citations – More Points of Difference in Citation Practice § 2-230. Medium-Neutral Case Citations § 2-240. Case Citations – Conditional Items § 2-250. Citing Unpublished Caseso § 2-300. Constitutions, Statutes, and Similar Materials § 2-310. Constitution Citations § 2-320. Statute Citations – Most Common Form § 2-330. Statute Citations – Conditional Items § 2-335. Statute Citations – Points of Difference in Citation Practice § 2-340. Statute Citations – Variants and Special Cases Session Laws Bills Named Statutes Internal Revenue Code Uniform Acts and Model Codes § 2-350. Local Ordinance Citations § 2-360. Treaty Citationso § 2-400. Agency and Executive Material § 2-410. Regulation Citations – Most Common Form § 2-415. Regulation Citations – Points of Difference in Citation Practice § 2-420. Regulation Citations – Variants and Special Cases § 2-450. Agency Adjudication Citations § 2-455. Agency Adjudication Citations – Points of Difference inCitation Practice § 2-470. Agency Report Citations § 2-480. Executive Orders and Proclamations – Most Common Formi

§ 2-490. Citations to Attorney General and Other Advisory Opinions –Most Common Formo § 2-500. Arbitration Decisionso § 2-600. Court Ruleso § 2-700. Books § 2-710. Book Citations – Most Common Form § 2-720. Book Citations – Variants and Special Cases Institutional Authors Services Restatements Annotationso § 2-800. Articles and Other Law Journal Writing § 2-810. Journal Article Citations – Most Common Form § 2-820. Journal Article Citations – Variants and Special Cases Student Writing by a Named Student Unsigned Student Writing Book Reviews Symposia and the Like Tributes, Dedications and Other Specially Labeled Articles Articles in Journals with Separate Pagination in Each Issueo § 2-900. Documents from Earlier Stages of the Same Case§ 3-000. EXAMPLES – CITATIONS OF .o § 3-100. Electronic Sourceso § 3-200. Judicial Opinions § 3-210. Case Citations – Most Common Form Federal State § 3-220. Case Citations – Variants and Special Cases § 3-230. Medium-Neutral Case Citations § 3-240. Case Citations – Conditional Itemso § 3-300. Constitutions, Statutes, and Similar Materials § 3-310. Constitutions § 3-320. Statute Citations – Most Common Form § 3-340. Statute Citations – Variants and Special Cases Session Laws Bills Named Statutes Internal Revenue Code Uniform Acts and Model Codes § 3-350. Local Ordinance Citations § 3-360. Treaty Citationso § 3-400. Regulations, Other Agency and Executive Material § 3-410. Regulation Citations – Most Common Form § 3-420. Regulation Citations – Variants and Special Cases § 3-450. Agency Adjudication Citations § 3-470. Agency Report Citations § 3-480. Citations to Executive Orders and Proclamationsii

§ 3-490. Citations to Attorney General and Other Advisory Opinionso § 3-500. Arbitration Decisionso § 3-600. Court Ruleso § 3-700. Books § 3-710. Book Citations – Most Common Form § 3-720. Book Citations – Variants and Special Cases Institutional Authors Services Restatements Annotationso § 3-800. Articles and Other Law Journal Writing § 3-810. Journal Article Citations – Most Common Form § 3-820. Journal Article Citations – Variants and Special Cases Student Writing by a Named Student Unsigned Student Writing Book Reviews Symposia and the Like§ 4-000. ABBREVIATIONS AND OMISSIONS USED IN CITATIONSo § 4-100. Words in Case Nameso § 4-200. Case Historieso § 4-300. Omissions in Case Nameso § 4-400. Reporters and Courtso § 4-500. Stateso § 4-600. Monthso § 4-700. Journalso § 4-800. Spacing and Periodso § 4-900. Documents from Earlier Stages of a Case§ 5-000. UNDERLINING AND ITALICSo § 5-100. In Citationso § 5-200. In Texto § 5-300. Citation Items Not Italicized§ 6-000. PLACING CITATIONS IN CONTEXTo § 6-100. Quotingo § 6-200. Citations and Related Texto § 6-300. Signalso § 6-400. Ordero § 6-500. Short Form Citations § 6-520. Short Form Citations – Cases § 6-530. Short Form Citations – Constitutions and Statutes § 6-540. Short Form Citations – Regulations § 6-550. Short Form Citations – Books § 6-560. Short Form Citations – Journal Articleso § 6-600. Context Exampleso § 6-700. Tables of Authorities§ 7-000. REFERENCE TABLESo § 7-100. Introductioniii

§ 7-200. Significant Changes in The Bluebook§ 7-300. Cross Reference Table: The Bluebook§ 7-400. Cross Reference Table: ALWD Guide to Legal Citation§ 7-500. Table of State-Specific Norms and PracticesTOPICAL INDEXoooo iv

PREFACEContents IndexThis work first appeared in 1993. It was most recently revised in October of 2019 to updatethe links to state rules and several other external resources. Like all prior revisions this oneincluded a thorough review of the relevant rules of appellate practice of federal and statecourts. The guide takes account of the latest editions of the ALWD Guide to LegalCitation (2017), The Bluebook, published in 2015, and The Supreme Court's Style Guide.Point-by-point, it is linked to the free citation guide, The Indigo Book. As has been true of alleditions released since 2010, it is also indexed to the The Bluebook and the ALWD Guide.Importantly, however, it documents the many respects in which contemporary legal writing,very often following guidelines set out in court rules or local style guides, diverges from thecitation formats specified by those academically produced and focused reference works. Thework's current online format, introduced in early 2016, was created with the assistance ofstudents enrolled in a graduate software engineering course at Cornell.The content of this ebook version is conformed to the 2020 Web edition, located at:https://www.law.cornell,edu/citation/. It can be used on a variety of electronic devices andprinted out, in whole or part, from some.A Few Tips on Using Introduction to Basic Legal CitationThis is not a comprehensive citation reference work. Its limited aim is to serve as a tutorial onhow to cite the most widely referenced types of U.S. legal material, taking account of localnorms and the changes in citation practice forced by the shift from print to electronic sources.It begins with an introductory unit. That is followed immediately by one on "how to cite" thecategories of authority that comprise a majority of the citations in briefs and legalmemoranda. Using the full table of contents one can proceed through this material insequence. The third unit, organized around illustrative examples, is intended to be used eitherfor review and reinforcement of the prior "how to" sections or as an alternative approach tothem. One can start with it since the illustrative examples for each document type are linkedback to the relevant "how to" principles.The sections on abbreviations and omissions, on typeface (italics and underlining), and onhow citations fit into the larger project of legal writing that follow all support the precedingunits. They are accessible independently and also, where appropriate, via links from theearlier sections. Finally, there are a series of cross reference tables tying this introduction tothe two major legal citation reference works and to state-specific citation rules and practices.The work is also designed to be used by those confronting a specific citation issue. For suchpurposes the table of contents provides one path to the relevant material. Another path, towhich the bar at the top of each major section provides ready access, is a topical index. Thisindex is alphabetically arrayed and more detailed than the table of contents. Finally, thesearch function in your e-book reader software should allow an even narrower inquiry, suchv

as one seeking the abbreviation for a specific word (e.g., institute) or illustrative citations for aparticular state, Ohio, say.If the device on which you are reading this e-book allows it, the pdf format will enable you toprint or to copy and paste portions, large or small, into other documents. However, since thework is filled with linked cross references and both the table of contents and index rely onthem, most will find a print copy far less useful than the electronic original.Help with Citation Issues Beyond the Scope of this WorkThe "help" links available throughout the work lead back to this preface and its tips on how tofind specific topics. Being an introductory work, not a comprehensive reference, this resourcehas a limited scope and assumes that users confronting specialized citation issues will have topursue them into the pages of The Indigo Book, The Bluebook, the ALWD Guide to LegalCitation, or a guide or manual dealing with the citation practices of their particularjurisdiction. The cross reference tables in sections 7-300 (Bluebook) and 7-400 (ALWD),incorporated by links throughout this work, are designed to facilitate such out references.Wherever you see [ BB ALWD IB] at the end of a section heading you can obtain direct pointers tomore detailed material in The Bluebook (by clicking on BB), the ALWD Guide to LegalCitation (ALWD), or link directly to the pertinent portion of The Indigo Book.Comments, Corrections, ExtensionsFeedback on this e-book would be most welcome. What doesn't work, isn't clear, is missing,appears to be in error? Has a change occurred in one of the fifty states that should bereported? Comments of these and other kinds can be sent by email addressedto peter.martin@cornell.edu. (Please include "Citation" in the subject line.) Many of thefeatures and some of the coverage of this reference are the direct result of past user questionsand advice. The current version benefited enormously from the close editorial scrutiny of oneof them. My thanks to Roger Sperberg. Comments of these and other kinds can sent by emailaddressed to peter.martin@ cornell.edu with the word "Citation" appearing in the subject line.Many of the features and some of the coverage of this reference are the direct result of pastuser questions and advice.Additional ResourcesA complementary series of "Citing . in brief" video tutorials offers a quick start introductionto citation of the major categories of legal sources. These videos are also useful for review.Currently, the following are available:1. Citing Judicial Opinions . in Brief (8.5 minutes)2. Citing Constitutional and Statutory Provisions . in Brief (14 minutes)3. Citing Agency Material . in Brief (12 minutes)vi

Finally, for those with an interest in current issues of citation practice, policy, and instruction,there is a companion blog, "Citing Legally," at: http://citeblog.access-to-law.com.vii

§ 1-000. BASIC LEGAL CITATION: WHAT AND WHY? [BB ALWD]§ 1-100. IntroductionContents Index Help When lawyers present legal arguments and judges write opinions, they cite authority. Theylace their representations of what the law is and how it applies to a given situation withreferences to statutes, regulations, court rules, and prior appellate decisions they believe to bepertinent and supporting. They also refer to persuasive secondary literature such as treatises,restatements, and journal articles. Court rules go so far as to authorize judges to rejectarguments that are not supported by cited authority. Lawyers who appeal on the basis ofarguments for which they have cited no authority can be sanctioned. As a consequence, thosewho would read law writing and do law writing must master a new, technical language: "legalcitation."For many years, the authoritative reference work on "legal citation" was a manual written andpublished by a small group of law reviews. Known by the color of its cover, TheBluebook was the codification of professional norms that introduced generations of lawstudents to "legal citation." So completely do many academics, lawyers, and judges identifythe process with that book they may refer to putting citations in proper form as "Bluebooking"or ask a law student or graduate whether she knows how to "Bluebook." The most recentedition of The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation, the twenty-first, was published in2020. In 2000 a competing reference appeared, one designed specifically for instructional use.Prepared by the Association of Legal Writing Directors, the ALWD Guide to LegalCitation (6th ed. 2017) has won wide acceptance in law school legal writing programs.Expansive copyright and trademark claims by the proprietors of The Bluebook spawned thelatest entry in the field, The Indigo Book, released in 2016. Working under the guidance ofNYU copyright expert, Professor Christopher Sprigman, a team of students spent over a yearmeticulously separating the “system of citation” reflected in The Bluebook from that manual’sexpressive content—its language, examples, and organization. The Indigo Book is the result.Like the ALWD Guide to Legal Citation, it endeavors to instruct those who would write legalbriefs or memoranda on how to cite U.S. legal materials in conformity with the system ofcitation codified in the most recent edition of The Bluebook while avoiding infringement ofthat work's copyright. Unlike the other two guides, it is free and can be copied withoutpermissionDifferences among these guides are microscopic (and noted here). In the way that dictionariesboth prescribe and reflect usage, so do these manuals. All three reflect their origins. They areprepared in law schools with large print libraries and access to the most expensivecommercial online legal information systems. Their principal focus is on the type of writingthat law students and law professors do and that academic law journals publish. The realitiesof professional practice in many settings, particularly at a time when digital distribution oflegal materials has largely displaced print, lead to dialects or usages in legal citation none ofthese manuals includes. And the type of writing required of lawyers and judges and thecontext lead to citation practices quite different from those appropriate to published articles.This introduction to legal citation is focused on the forms of citation used in professionalpractice rather than those used in journal publication. For that reason, it does not cover thedistinct typography rules for the latter. Furthermore, it aims to identify the more important1

points on which there is divergence between the rules set out in the major manuals andevolving usage reflected in legal memoranda and briefs prepared by practicing lawyers.As is true with other languages, learning to read "legal citation" is easier than learning to writeit fluently. The active use of any language requires greater mastery than the receiving andunderstanding of it. In addition, there is the potential confusion of dialects or othernonstandard forms of expression. As already noted, "legal citation," like other languages, doesindeed have dialects. Most are readily understandable and thus pose little likelihood ofconfusion for a reader. To the beginning writer, however, they present a serious risk ofmisleading and inconsistent models. As a writer of "legal citation," you must take care thatyou check all references that you find in the work of others. This includes citations in courtopinions. The nation’s highest court has its own distinctive citation style. In addition,commercial publishers have long viewed citation as a subtle form of advertising throughbranding. Thus, citations in decisions published in the multiple series of the NationalReporter System of the Thomson Reuters unit known as Thomson West (from the AtlanticReporter to the Federal Supplement) have been altered by its editors to refer to other Westpublications. Several important state courts, California, Illinois, and New York among them,have idiosyncratic citation norms for their own decisions. Many more cite their state's statutesand administrative regulations without repetition of a full abbreviation of the state’s name ineach reference, that being implied by context. While each of these courts is likely to accept—indeed, may even prefer—briefs using the same citation dialect, Federal courts in the samestate may not. In short, copying and pasting citations from decisions and other references intoone’s own writing is almost certain to yield inconsistent, nonstandard, and even incompletecitations.Changes in citation norms over time also caution against relying on source material for propercitation form. The Bluebook has been revised five times in the past twenty years, in 2000,2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 (see § 7-200). Because of these changes, citations you find inlegal documents published in prior years, although they may have been totally conformed tocitation standards at the time of writing, may need reformatting to comply with current ones.In other words, imported citations, even those imported from the most carefully edited pre2020 journal articles, books, or opinions, may not be in proper current form. It should also benoted that The Bluebook itself has throughout these revisions set forth two distinct versions ofcitation—one for journals and an alternative set of "practitioner rules."What about the feature now part of many online services that enables users to block text andcopy it together with its "citation" into their notes? With some services users are even invitedto select among a number of different citation formats. Regrettably, even the best (and mostexpensive) do not remove the need for researchers to know and apply the detailed citationnorms applicable to the brief or memorandum they will ultimately prepare. There are severalreasons for this gap between promise and performance. To begin, the most prominent servicescontinue to view citation as a means of branding. Any statutory provision retrieved withcitation from Westlaw or Lexis will cite to the publisher’s proprietary version of thejurisdiction's code rather than provide the reference in its official or generic format. Casecitations retrieved from Westlaw give unnecessary prominence to the publisher’s NationalReporter System volume and page numbers. Secondly, none of the services delivers all theinformation that a writer will need for a complete citation across all types of material. Some2

fail to include the page or paragraph number of a specific passage copied from within a case.All fail to include the subsection, paragraph, and subparagraph numbers of a copied statutoryor regulatory provision. What this means is that before you can safely rely on citationsdelivered by an online service you must have mastered legal citation sufficiently to knowwhat additional information you will need to append to them manually in your notes, whatportion of the citations furnished you can safely delete, and the extent to which you will needto reformat what remains. See Copy with Reference, https://citeblog.access-tolaw.com/?p 1103Few people find a dictionary the best starting point for learning a new language. For many ofthe same reasons neither The Bluebook, the ALWD Guide to Legal Citation, nor The IndigoBook is a good primer. Like dictionaries, these manuals are designed as comprehensivereference works. This introduction refers to them throughout. But while they aim atexhaustive coverage, these materials seek to introduce the basics through concise statementsof principles and usage linked to examples. The aim is not to separate you from a fullreference work; inevitably you will encounter unusual situations that require "looking up" theproper "rule" or abbreviation in a more comprehensive manual. Instead, this introduction aimsat building a basic mastery of "legal citation" as codified in the major references—a level ofmastery that should enable you to do all of your legal reading and much of your legal writingwithout having to reach for them. Since The Bluebook and the ALWD Guide to LegalCitation embrace the full range of journal writing, they furnish guidance on how to cite allmanner of references infrequently used in practitioner writing, including a variety of foreignlaw materials and historic references. By contrast, this introduction is limited to contemporaryU.S. legal material.Because this introduction is not a substitute for a comprehensive reference, you would be wiseto introduce yourself to one as you proceed through this material. Read through its table ofcontents and introductory material. Each topic covered here includes links to tables providingreferences to coverage in The Bluebook and the ALWD Guide to Legal Citation, as well aslinks directly into The Indigo Book itself. Observing how the manual that you have chosen (orothers have chosen for you) arrays its more detailed treatment should be part of your initialexploration of each topic here.There is no question but that striving for proper citation form will for a time seem a sillydistraction from the core project of writing. But as is true with other languages, those who usethis one carefully make negative assumptions about the craft of those who don't. Being asimple language at its core, this one should fairly quickly become a matter of habit and, thus,no longer a distraction.§ 1-200. Purposes of Legal CitationContents Index Help What is "legal citation"? It is a standard language that allows one writer to refer to legalauthorities with sufficient precision and generality that others can follow thereferences. Because writing by lawyers and judges is so dependent on such references, it is alanguage of abbreviations and special terms. While this encryption creates difficulty for layreaders, it achieves a dramatic reduction in the space consumed by the, often numerous,references. As you become an experienced reader of law writing, you will learn to follow a3

line of argument straight through the many citations embedded in it. Even so, citations are abother until the reader wishes to follow one. The fundamental tradeoff that underlies anycitation scheme is one between providing full information about the referenced work andkeeping the text as uncluttered as possible. Standard abbreviations and codes help achieve areasonable compromise of these competing interests.A reference properly written in "legal citation" strives to do at least three things, withinlimited space: identify the document and document part to which the writer is referringprovide the reader with sufficient information to find the document or document partin the sources the reader has available (which may or may not be the same sources asthose used by the writer), andfurnish important additional information about the referenced material and itsconnection to the writer's argument to assist readers in deciding whether or not topursue the reference.Consider the following illustration of the problem faced and the tradeoff struck by "legalcitation." In 1989, the Supreme Court decided an important copyright case. There arecountless sources of the full text opinion. One is Lexis Classic, where the following appearsprior to the opinion. If a lawyer, wanting to refer to all or part of that opinion, were to includeall that identifying material in her brief (with a similar amount of identifying material forother authorities) there would be little room for anything else. Readers of such a brief wouldhave an impossible time following lines of argument past the massive interruptions ofcitation.Cmty. For Creative Non -Violence v. ReidSupreme Court of the United StatesMarch 29, 1989, Argued; June 5, 1989, DecidedNo. 88-293Reporter490 U.S. 730 * 109 S. Ct. 2166** 104 L. Ed. 2d 811*** 1989 U.S. LEXIS 2727 **** 10U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1985 57 U.S.L.W. 4607 Copy. L. Rep. (CCH) P26,425 16 Media L.Rep. 1769March 29, 1989, ArguedJune 5, 1989, DecidedPrior History: CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FORTHE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT.4

Disposition: 270 U. S. App. D. C. 26, 846 F. 2d 1485, affirmed.In standard "legal citation," the reference to this opinion becomes simply:Cmty. for Creative Nonviolence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989).With economy this identifies the document and allows another lawyer to retrieve the decisionfrom a wide range of print and electronic sources. The "identifier" of "490 U.S. 730" sufficesfor a reader who has access to West's Supreme Court Reporter published by Thomson Reutersor to the Lawyers' Edition, Second Series published in print and online by LexisNexis. It alsosuffices with Lexis, Westlaw, Bloomburg Law, Fastcase, Google Scholar, and the myriadother online sources of Supreme Court decisions. Enter "490 U.S. 730" as a search on Googleand it will lead directly to the decision. The rest of the citation tells the reader that this is a1989 decision of the United States Supreme Court (and not, say, a recent opinion of a U.S.District Court) and who the parties were.The task of "legal citation" in short is to provide sufficient information to the reader of a briefor memorandum to aid a decision about which authorities to check as well as in what order toconsult them and to permit efficient and precise retrieval – all of that, without consuming anymore space or creating any more distraction than is absolutely necessary.5

§ 1-300. Types of Citation PrinciplesContents Index Help The detailed principles of citation can be conceived of as falling into four categories:Full Address Principles: Principles that specify completeness of the address oridentification of a cited document or document portion in terms that will allow the reader toretrieve it.Other Minimum Content Principles: Principles that call for the inclusion in a citation ofadditional information items beyond a retrieval address – the full name of the author of ajournal article, the year a decision was rendered or a book, published. Some of theseprinciples are conditional, that is, they require the inclusion of a particular item underspecified circumstances so that the absence of that item from a citation represents that thosecircumstances do not exist. The subsequent history of a case must be indicated when itexists, for example; the edition of a book must be indicated if there have been more thanone. Most of these additional items either furnish a "name" for the cited document orinformation that will allow the reader to evaluate its importance.Compacting Principles: Principles that reduce the space taken up by the information itemsincluded in a citation. These include standard abbreviations ("United States Code" becomes"U.S.C.") and principles that eliminate redundancy. (If the deciding court is communicatedby the name of the reporter, it need not be repeated in the citation's concluding parenthesesalong with the date as it should otherwise be.)Format Principles: Principles about punctuation, typography, order of items within acitation, and the like. Such principles apply to the optional elements in a citation as well asthe mandatory ones. One need not report to the reader that a cited Supreme Court case wasdecided 5-4; but if one does, there is a standard form.§ 1-400. Levels of MasteryContents Index Help What degree of mastery of this language should one strive for – as a student, legal assistant, orlawyer?Recall that a citation serves several purposes. Of those purposes, one is paramount –furnishing accurate and complete information that will enable retrieval of the cited documentor document part. The element of citation that calls for immediate mastery is painstaking carein recording and presenting the complete address or retrieval ID of a document. Citing a caseusing the wrong volume or page number, citing a statute with an erroneous section number orwithout a necessary title number – errors like these cannot be explained away by theintricacies of citation. Their negative impact on readers is palpable. Consider the frustrationyou experience when you are given an erroneous or partial street address or an email addressthat fails because of a typo; a judge's reaction to an erroneous citation is likely to be quitesimilar.6

Since, in many cases, part of the clear address to a cited document includes an abbreviation, asmall set of abbreviations must be mastered as soon as possible. A minimum set includesthose that represent the reporters for contemporary federal decisions, those that representcodified federal statutes and regulations, and those that represent the regional reporters ofstate decisions. Whenever your research is centered in the law of a particular state, you willwant also to memorize the abbreviations that represent the case reports, statutorycompilations, and regulations of that state.Less critical in terms of function but no more difficult to master are the abbreviations thatindicate the deciding court when that information is not implicit in the name of thereporter. You should strive to master the abbreviations for the circuits of the U.S. Courts ofAppeals and those for the U.S. District Courts. Any time your research is centered in the lawof a particular state you will want to master the abbreviations for its different courts.Last and least are the conventions for reducing the space consumed by case names and journaltitles. Including the full word "Environmental" in a case name rather than the

§ 2-100. Electronic Sources § 2-110. Electronic Sources - Core Elements § 2-115. Electronic Sources - Points of Difference in Citation Practice § 2-120. Electronic Sources - Variants and Special Cases . o § 2-200. Judicial Opinions § 2-210. Case Citations - Most Common Form § 2-215.

[This Page Intentionally Left Blank] Contents Decennial 2010 Profile Technical Notes, Decennial Profile ACS 2008-12 Profile Technical Notes, ACS Profile [This Page Intentionally Left Blank] Decennial 2010 Profile L01 L01 Decennial 2010 Profile 1. L01 Decennial 2010 Profile Sex and Age 85 and over 80 84 75 79 70 74

This page intentionally left blank. This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America: The Impact of Climate Change to 2030 A Commissioned Research Report . This page is intentionally kept blank.

Source: AFP PHOTO/KCNA VIA KNS Information cutoff date, February 2018. DIA-05-1712-016. INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK. INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK. DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY V GLOBA UCLEA LANDSCAE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Executive Summary VI. Section One: Russia 8 .

Part Number Suffix Polyamide Cage TNG/TNH TN9 TVP, TVH -- PRB Steel Cage Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank 2 Contact Seals 2RS 2RS1 2RSR LLU PP 2 Shields 2Z 2Z 2ZR ZZ FF Tight Clearance C2 C2 C2 C2 H Normal Clearance Blank Blank Blank Blank R Greater than Normal Clearance C3 C3 C3 C3 P Interchange Nomenclature 32 10 Basic Type & Series

Anesthesia: Blank Blank: Blank Blank: 2.43 5% Sample: 10004 Blank FNA BX W/O IMG GDN EA ADDL; Surgery Blank; 0.80 0.34; 0.58 Blank; RBRVS 10005 Blank; FNA BX W/US GDN 1ST LES Surgery

This page intentionally left blank . TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-8 . i Preface . From the Commander . . (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) to Director, TRADOC ARCIC (ATFC- ED), 950 Jefferson Avenue, Fort Eustis, VA 23604 - 5763. Suggested improvements may also be submitted using DA Form 1045 (Army Ideas for Excellence Program .

This page intentionally left blank [50] Develop computer programs for simplifying sums that involve binomial coe-cients. . satisfy one; see theorems 4.4.1 on page 65 and 6.2.1 on page 105). The output recurrence will look like eq. (6.1.3) on page 102. In this example zeilprints

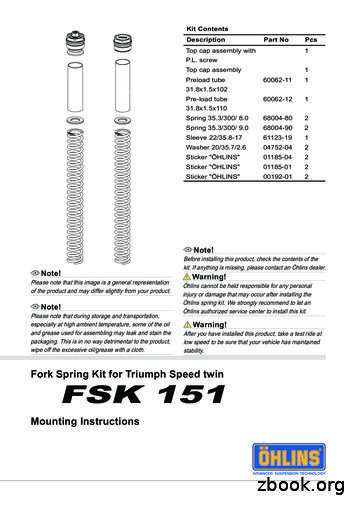

LEFT FORK LEG RIGHT FORK LEG. 3 MNTIN INSTRTINS Öhlins Front Fork kit assembly 60206-03 21907-03 00338-83 60005-39 21906-03 21903-01 00338-42 7: 04752-04 . This page intentionally left blank. This page intentionally left blank. Öhlins sia o. Ltd 700/937 Moo5, Tambol Nongkhaga, mphur Phantong, honburi Province