Improving Our Maternity Care Now Through - National Partnership For .

Improving Our Maternity Care Now ThroughMidwiferyOctober 2021

Executive SummaryOur nation’s maternity care system fails to provide many childbearing people* and newbornswith equitable, accessible, respectful, safe, effective, and affordable care. More people die percapita from pregnancy and childbirth in this country than in any other high-income countryin the world. Our maternity care system spectacularly fails communities struggling with theburden of structural inequities due to racism and other forms of disadvantage, including Black,Indigenous, and other communities of color; rural communities; and people with low incomes.Both the maternal mortality rate and themuch higher severe maternal morbidity rate(often reflecting a “near miss” of dying) havebeen increasing, and both reveal inequitiesby race and ethnicity. Relative to white nonHispanic women, Black women are more thanthree times as likely – and Indigenous womenare more than twice as likely – to experiencepregnancy-related deaths. Moreover, Black,Indigenous, Hispanic, and Asian and PacificIslander women disproportionately experiencebirths with severe maternal morbidity relativeto white non-Hispanic women.This dire maternal health crisis, which hasbeen compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic,demands that we mitigate needless harm now.Fortunately, research shows that thereare specific care models that can make aconcrete difference in improving maternitycare quality and producing better outcomes,especially for birthing people of color. Oneof these models is midwifery care. Thisreport outlines the evidence that supportsmidwifery’s unique value across differentcommunities, the safety and effectivenessof midwifery care in improving maternaland infant outcomes, the interest of birthingpeople in midwifery care, and the currentavailability of, and access to, midwiferyservices in the United States. We also providerecommendations for key decisionmakers inpublic and private sectors to help supportand increase access to midwifery care.Research shows that midwifery care providesequal or better care and outcomes comparedto physician care on many key indicators,including higher rates of spontaneousvaginal birth, higher rates of breastfeeding,higher birthing person satisfaction with care,and lower overall costs. Community-basedand -led midwifery services are especiallypowerful. Yet in the United States, midwivesattend only about 10 percent of births; innearly all other nations, midwives providethe majority of first-line maternity care tochildbearing people and newborns, with farbetter outcomes.* We recognize and respect that pregnant, birthing, postpartum, and parenting people have a range of genderidentities, and do not always identify as “women” or “mothers.” In recognition of the diversity of identities, thisreport gives preference to gender-neutral terms such as “people,” “pregnant people,” and “birthing persons.” Inreferences to studies, we use the typically gendered language of the authors.NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES2

Expanding the availability of midwiferycare is a cost-effective solution toproviding higher quality care and betterbirth outcomes. Barriers to this modalityof care must be eliminated. Theseinclude: lack of support and funding formidwifery education, inconsistent Medicaidreimbursement for midwifery services, lackof state-level recognition of all nationallyrecognized midwifery credentials, andrestrictive state practice laws that prohibitmidwives from practicing to the full scope oftheir competencies and education.Enabling more birthing people to receivecare from midwives while diversifying theprofession of midwifery should be a toppriority for decisionmakers at the local,state, and federal levels. To achieve this, werecommend the following: Prohibit hospitals from denyingadmitting and clinical privileges tomidwives as a class. Require the collection and publicreporting of data related to healthinequities, such as racial, ethnic,socioeconomic, sexual orientation,gender identity, language, and disabilitydisparities in critical indicators ofmaternal and infant health – including,but not limited to, maternal mortality,severe maternal morbidity, pretermbirth, low birth weight, cesarean birth,and breastfeeding.State and territorial policymakers should: Ensure that their states licenseand regulate all nationally certifiedmidwifery credentials. Amend restrictive midwifery and nursepractice acts to enable full-scopemidwifery practice , in line with theirfull competencies and education asindependent providers who collaboratewith others according to the healthneeds of their clients. Mandate reimbursement of midwiveswith nationally recognized credentialsat 100 percent of physician paymentlevels for the same service in stateswithout payment parity. In states where Medicaid agencies donot currently pay for the services oflicensed midwives holding nationallyrecognized midwifery credentials,mandate payment at 100 percent ofphysician payment levels for the sameservices.Federal policymakers should: Enact the bipartisan Midwives forMaximizing Optimal Maternity Services(Midwives for MOMS) Act (H.R. 3352 andS. 1697 in the 117th Congress) to increasethe supply of midwives with nationallyrecognized credentials (certified nursemidwives, certified midwives, certifiedprofessional midwives), racially andethnically diversify the midwiferyworkforce, and increase access to carein underserved areas.Mandate equitable payment formidwifery services by all federal healthprograms and make certified midwivesand certified professional midwiveseligible for federal loan repaymentfrom the National Health Service Corps.NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES3

Private sector decisionmakers, includingpurchasers and health plans, should: Incorporate clear expectations intoservice contracts about access to, andsustainable payment for, midwiferyservices offered by providers withnationally recognized credentials.Educate employees and beneficiariesabout the benefits of maternity careprovided by midwives with nationallyrecognized credentials.NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES Mandate that plan directories maintainup-to-date listings for availablemidwives.In all relevant deliberations, consistentlyengage early and proactively withcommunity-based midwives bringing abirth justice framework. This involves theirmeaningful decision-making roles in shapingpolicy priorities and strategies, and diverserepresentation that reflects the demographicmakeup of adversely affected communities.4

Improving Maternity Care Through MidwiferyThe U.S. maternity care system fails to provide many childbearing people† and newborns withequitable, accessible, respectful, safe, effective, and affordable care.1 More people die percapita as a result of pregnancy and childbirth in this country than in any other high-incomenation.2 Our maternity care system spectacularly fails communities struggling with the burdenof structural inequities due to racism and other forms of disadvantage, including Black,Indigenous, and other communities of color; rural communities; and people with low incomes.3Rates of maternal death and severe maternalmorbidity in the United States have beenworsening instead of improving. In 2019, theU.S. maternal mortality rate was 20.1 per100,000 live births, a significant increaseover the maternal mortality rate in 2018 (17.4per 100,000 live births).4 Between 1987 and2017, pregnancy-related deaths in the UnitedStates more than doubled – from 7.2 to 17.3deaths per 100,000 live births.5 Between 2006and 2015, severe maternal morbidity (SMM),often reflecting a “near miss” of dying, roseby 45 percent, from 101.3 to 146.6 per 10,000hospitalizations for birth.6 Following the 2015shift to a new clinical coding system (ICD10-CM/PCS), SMM continued to show a trendof increase, overall and for people of color,from 2016 to 2018.7In communities of color, the crisis is fargreater. Compared to white non-Hispanicwomen, Black women are more than threetimes as likely – and Native women aremore than twice as likely – to experiencepregnancy-related deaths. Moreover, Black,Hispanic, and Asian and Pacific Islander†women disproportionately experiencebirths with SMM relative to white nonHispanic women.8 In 2015, relative to whitenon-Hispanic women, the rate of SMMwas 2.1 times higher for Black women, 1.3times higher for Hispanic women, and1.2 times higher for Asian and PacificIslander women.9 From 2012 through 2015,Indigenous women experienced 1.8 timesthe SMM rate of white women.10Many factors drive maternal mortality andmorbidity and the deep racial, ethnic, andgeographic inequities in this area. Theseinclude gaps in health coverage and accessto care; poor quality care, including implicitbiases and explicit discrimination; unmetsocial needs, like transportation and timeoff from paid work for medical visits andsafe and secure housing; and for people ofcolor, the effects of contending with systemicracism.11 The terrible impacts of theseinequities are unconscionable, especiallyconsidering that 60 percent of pregnancyrelated deaths are preventable.12We recognize and respect that pregnant, birthing, postpartum, and parenting people have a range of genderidentities, and do not always identify as “women” or “mothers.” In recognition of the diversity of identities, this reportgives preference to gender-neutral terms such as “people,” “pregnant people,” and “birthing persons.” In references tostudies, we use the typically gendered language of the authors.NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES5

In the long term, we must transform thematernity care system through levers suchas delivery system and payment reform,performance measurement, consumerengagement, health professions education,and the improvement of the workforcecomposition and distribution. However, ourdire maternal health crisis, which has beencompounded by the COVID-19 pandemic,demands that we mitigate needless harm now.Fortunately, research shows that there arespecific care models that make a concretedifference in providing higher quality careand improving birth outcomes. Midwiferycare is one example of better care that wemust make widely available, especially forbirthing people and families of color.§Midwifery in the United States.Midwifery provides high-quality and highvalue care to childbearing people. Ingeneral, midwifery is a high-touch, low-techapproach to maternity care. The midwiferymodel is based on the core understandingthat childbearing for most birthingpeople is a healthy process that requiresprotecting, supporting, and promotinginnate physiologic processes and monitoringto identify when higher levels of care areneeded. It centers the childbearing personand family. The midwifery model of careemphasizes a trusted relationship, healthpromoting practices, providing informationthat birthing people need to make theirown care decisions, and personalized caretailored to individual needs and preferences.§In nearly all nations, midwives provide firstline maternity care to childbearing peopleand newborns. However, in the United States,the vast majority of births are attended byobstetricians, while midwives attend only about10 percent of births.13 In the early 20th century,pregnancy and childbirth in the United Stateswere reframed as medical – even pathological– conditions, rather than what in most caseswas a healthy physiologic life process. Birthingshifted from happening at home, attended bymidwives of all backgrounds and traditions, tooccurring in hospitals dominated by white menwho saw childbirth as a medical problem tobe solved with an array of drugs, treatments,and interventions. Medicine’s denigration andelimination of Black, Indigenous, immigrant,and other community midwives is anotherexample of racism pervading our society andhealth care system.14 Both racism15 and genderbased violence toward birthing people16 havebeen well documented in obstetrics.In contrast to the medical focus on childbirthpathology, physiologic childbirth approachesbirthing from a more holistic frame that avoidsunneeded medical interventions. This type ofcare, which is a hallmark of much midwiferycare, actively supports the innate capabilitiesof birthing people and their fetus or newbornfor labor, birth, breastfeeding, and attachment.Medical interventions are used judiciously,as needed, and not as routine practices.17Although any type of maternity care providercan theoretically offer the midwifery model ofcare and can foster physiologic birth, midwivesdo so most consistently.18To learn more about three other models of high-quality maternity care – doula support, “community birth” (birthcenters and planned home births), and community-led perinatal health worker groups – see our foundationalreport, Improving Our Maternity Care Now, at .NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES6

As in other countries, U.S. midwives holding nationallyrecognized credentials provide expert care for birthing people.The midwifery model of care is lesspathology-focused and procedure-intensivethan medical approaches to care of birthingpeople. For example, midwives regularlyuse non-pharmacologic tools to helpmanage pain, such as tubs and showers,hot and cold compresses, exercise balls,and massage. Hospital-based midwivesalso have access to epidural analgesia andother technologies. Dependent on hospitalprotocols and culture of practice, as well asthe needs and preferences of people withhospital births, the overall style of practiceof hospital-based midwives can involve moreinterventions than midwives practicing inbirth centers and at home.19Just as in the broader society and healthcare system, racism is present in midwifery.Since the transition to obstetric andhospital dominance, midwifery has beena disproportionately white profession.20Efforts to combat racism in midwifery anddiversify the profession are underway.21Culturally congruent community-based and-led models of midwifery care are especiallypowerful.22 The work of groups such asthe National Black Midwives Alliance andother birth justice organizations bringsan essential lens for conducting analysis,reclaiming suppressed traditions, andhealing racial harm and trauma.23As in other countries, U.S. midwives holdingnationally recognized credentials provideNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIESexpert care for birthing people. They areeducated to identify when a birthing personneeds higher levels of more specialized carethan midwives can provide. Midwives mayconsult, share care, transfer care, or transportbirthing people and newborns to specialtycare when higher risks and complicationsemerge.24 Most births in the United Statesoccur in hospitals, and most midwivesattend births in hospitals. However, nearly allmaternity care providers in birth center andhome birth settings are midwives.25The United States has three nationallyrecognized midwifery credentials witheducation programs recognized by theU.S. Department of Education: certifiednurse-midwives (CNMs), certified midwives(CMs), and certified professional midwives(CPMs). The latter two credentials wererecognized more recently, in the 1990s. Allthree credentials are accredited by theNational Commission for Certifying Agencies,the accrediting body of the Institute forCredentialing Excellence.Both CNMs and CMs have completedgraduate-level midwifery training accreditedby the Accreditation Commission forMidwifery Education (ACME). Both sit forthe same national certification examadministered by the American MidwiferyCertification Board (AMCB). CNMs arerequired to hold a nursing degree in additionto their midwifery training, while CMs are7

not. They both provide care in all threebirth settings (hospitals, birth centers, andhomes). While CNMs are licensed to practiceand are Medicaid and Medicare providers inall jurisdictions, CMs are currently recognizedin only nine states and can be paid byMedicaid in four.26The CPM credential requires knowledge andexperience in community birth – that is,care in birth centers or homes.27 Midwivesqualify to become CPMs through graduatingfrom a school accredited by the MidwiferyEducation Accreditation Council (MEAC) or bycompleting the Portfolio Evaluation Process(PEP). Regardless of route of education,all CPMs are required to achieve the sameclinical and academic competencies andsit for the national certification examadministered by the North American Registryof Midwives (NARM). The CPM credentialis competency-based; demonstratingachievement of the competencies isrequired, while a degree is not. Nonetheless,about half of all CPMs practicing in theUnited States hold a bachelor’s degree orhigher.28 Five of the MEAC-accredited schoolsconfer a diploma, and five confer associate,bachelor’s, or master’s degrees.29 Currently,34 states and the District of Columbia havea path to CPM licensure, with ongoing effortsfor legal recognition in the remaining statesand U.S. territories. Medicaid covers CPMservices in 16 jurisdictions.30Midwives with Nationally Recognized Credentials:CNMs, CMs and CPMs31SettingLegal recognitionMedicaidcoverageCertifiedRN master’snursedegreemidwife (CNM)Hospital, birthcenter, homeAll states, DC,U.S. territories*Yes, by federalstatuteCertifiedmidwife (CM)Bachelor’s master’s degreeHospital, birthcenter, home9 states: DE, HI,ME, MD, NJ, NY,OK, RI, VA4 states: ME, MD,NY, RICertifiedprofessionalmidwife (CPM)High schooldiploma orequivalent; mayearn certificate,associate’s,bachelor’s, ormaster’s degreeBirth center,home34 states DC (allexcept CT, GA, IA,IL, KS,MA, MO, MS, ND,NE, NC, NY, NV,OH, PA, WV, andU.S. territories)15 states DC: AK,AZ, CA, DC, FL, ID,MN (birth centersonly), NH, NM,OR, SC, TX (birthcenters only), VA,VT, WA, and WICredentialDegree*The U.S. territories are American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. VirginIslands.NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES8

Midwifery care provides equalor better outcomes compared tousual careSeveral systematic reviews** have comparedthe care and outcomes of midwives andphysicians. Compared to physician care,midwifery care resulted in: Increased use of intermittentauscultation (instead of continuouselectronic fetal monitoring) Less use of epidural or spinal analgesia Less use of pain medication overall Fewer episiotomies Increased spontaneous vaginal birth(with neither forceps nor vacuum) More vaginal births after a cesarean Greater initiation of breastfeeding Better psychological experience(e.g., sense of control or confidence,satisfaction) Lower costsPhysicians and midwives produced similarresults with regard to: Use of IV fluids in labor Maternal hemorrhage (excess bleeding) Signs of fetal distress in labor Condition of newborn just after birth Admission to a neonatal intensive careunit (NICU) Fetal loss or newborn deathFor some indicators, systematic reviews variedin their conclusions. Compared to physicians,midwives had similar or better results for: Hospitalization in pregnancy Preterm birth Low birth weight Labor induction Use of medicine to speed labor Cesarean birth32Other researchers have found that statesthat have more fully integrated midwiferycare tend to have better maternal and infanthealth outcomes. More integrated states(measured by indicators such as regulationof the profession, Medicaid payment for theirservices, and the degree to which regulationssupport autonomous practice) were morelikely to report higher rates of physiologicchildbearing, lower rates of cesarean andother obstetric interventions, lower risk ofadverse newborn outcomes (preterm birth,low birth weight, and infant mortality), andincreased breastfeeding both at birth and atsix months postpartum.33Similarly, the availability of midwifery care atthe hospital level has been associated withless use of labor induction, medication tospeed labor, and cesarean birth, and greaterlikelihood of vaginal birth, including vaginalbirth after a cesarean, than hospitals withphysician-only maternity services.34** A systematic review is a method of assessing the weight of the best available evidence about possible benefits andharms of interventions or exposures. An investigation by the Institute of Medicine found that this rigorous methodologyis the best way of “knowing what works in health care.” Institute of Medicine. Knowing What Works in Health Care: ARoadmap for the Nation. (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.17226/12038NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES9

Midwives who provide racially centered or congruent carecan offer childbearing people of color valued supportthrough their focus on racial justice and commitment tocombating inequity, care that is likely to be experienced asphysically and emotionally safe.Higher percentages of midwife-attendedbirths at hospitals have been associated withlower rates of cesarean birth and episiotomy.35In light of the intractable maternal health crisisplaguing the country, investing more resourcesin training and supporting high-quality, highvalue midwifery care is a powerful strategyfor rapidly expanding access to effectivematernity care services. Compared to the timeand money it takes to train an obstetrician orfamily physician, midwives can be educated toserve pregnant people and their families morequickly and at a lower cost.36 Thus, midwifery isan expedient pathway to a more diverse cadreof maternity care providers that more closelymirrors the racial and ethnic composition ofchildbearing people.People have positive experienceswith midwifery care and interest inusing it is highIn recent years, concerns about disrespectfulmaternity care have come to the fore, andmany childbearing people – including thosewith tragic outcomes – have reported beingignored, having their concerns dismissed,not having choices in care, and otherwisebeing mistreated.37 Two systematic reviewsfound that people who received midwiferycare were more likely to report feeling moreNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIEScontrol, confidence, and satisfaction thanpeople who received physician-led care.38In addition, midwives who provide raciallycentered or congruent care can offerchildbearing people of color valued supportthrough their focus on racial justice andcommitment to combating inequity, care thatis likely to be experienced as physically andemotionally safe.39 Increasing the diversity ofthe midwifery profession would enable morebirthing people of color to obtain high-qualitycare that helps mitigate the racism embeddedin maternity and other types of health care.40Birthing people’s interest in midwifery carefar exceeds their current access and use. Forexample, in the population-based Listeningto Mothers in California survey, six times asmany participants with 2016 births indicatedan interest in midwifery care should theygive birth in the future, compared to peoplewho actually received midwifery care. Atotal of 54 percent expressed some degreeof interest, with 17 percent stating theywould definitely want midwifery care, and37 percent stating they would consider thistype of care provider. Interest was especiallyhigh among Black women (66 percent),and interest among women with Medi-Cal(California’s Medicaid program) was similarto that of women with private insurance.4110

Spotlight on SuccessMERCY BIRTHING CENTERThe Mercy Birthing Center illustrates the potential of a flourishing midwifery-led unitwithin a hospital. The center is a separate unit operated by CNMs within Mercy Hospital St.Louis. It was established in response to women’s growing interests in receiving support forphysiologic childbearing.42The homelike center includes four birthing suites with tubs and showers, a central living roomand kitchen, an area for classes, and rooms for prenatal and postpartum and newborn visits.43The center offers comfort measures as well as nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”) to help womencope with labor. The midwives use handheld devices for monitoring the fetal heart status(“intermittent auscultation”). In contrast to many typical hospital settings, laboring women arefree to eat, drink, and move about, according to their interest, and to give birth in their positionof choice. If they need higher levels of care (for example, an epidural or continuous electronicfetal monitoring) or develop a complication or concern, their midwife can accompany themupstairs to the standard labor unit and continue to care for them there. Care by obstetriciansand maternal-fetal medicine specialists is available if needed.44The center’s care and outcomes contrast sharply with standard hospital birthing care: Their cesarean rate is 70 percent lower than that national average (less than one out of10 births, compared to one in three). Their rate of vaginal births after a cesarean (VBAC) among women planning to haveone is up to 40 percent higher (84 percent compared to usual rates of 60 to 80 percent,depending on the study).45 Their episiotomy rate is only 0.4 percent, compared to 6.9 percent among hospitalsreporting in 2018 – more than 17 times higher.46 Their epidural rate was 6.4 percent, versus 75 percent nationally in 2019.47 Their labor induction rate (8.7 percent) was 68 percent lower than national ratesreported on 2019 birth certificates.ǂ, 48In addition to these excellent clinical outcomes, 100 percent of their clients reported theywould recommend this care to friends.ǂIt is importantto note thatcertificatesare known to greatly undercount inductions. For example,NATIONALPARTNERSHIPFOR birthWOMEN& FAMILIESwomen in California who gave birth in 2016 reported a rate of 40 percent.11

Access to midwifery care is limitedDespite the clear value of midwifery care,especially as a pathway to help solve thenation’s maternal health crisis and obtainbetter outcomes for birthing people andinfants, there are significant limitations to itsavailability. One indicator of limited access isthe gap between the number of people whosay they are interested in midwifery care –the majority – and the number who actuallyuse it, which is roughly one in 10. Anotherindicator of lack of access is that in 2017, 55percent of U.S. counties did not have a singlepracticing certified nurse-midwife or certifiedmidwife. Moreover, roughly one in three U.S.counties that year were considered maternitycare deserts, meaning that the county hadneither an obstetrician-gynecologist, nor anurse-midwife, nor a hospital maternity unit.49The American College of Obstetricians andGynecologists recommends increasing thenumber of midwives as an essential strategyto solve this access crisis.50 The availabilityof midwifery care is influenced by the supplyand distribution of midwives and birthingfacilities. CMs are only licensed in nine states,and CPMs still are not licensed in 16 statesand U.S. territories. A model legislationprocess undertaken by leading midwiferyorganizations points the way to robust,woman-centered midwifery legislation.51Another factor that limits the supply ofmidwives is the lack of consistent, systemicsupport for midwifery education andeducators, including preceptors, parallel toMedicare’s support for medical residencies.As a result, the burden on midwiferyeducators (as well as student tuitions) andon preceptors is great. This is also a limitingfactor in the availability of midwives toshare their distinctive knowledge and firstline approaches to maternal-newborn carewith medical students and trainees, andnursing and other students.52 The FurtherConsolidated Appropriations Act of 2020included 2.5 million for this purpose, and abill introduced in the current Congress wouldgreatly expand support for CNM, CM, andCPM accredited education. Both initiativesare grounded in an equity framing to helpwith the crucial goals of diversifying themidwifery profession and improving thegeographic distribution of midwives.Another barrier to increased access tomidwifery care is the time intensivenessDespite the clear value of midwifery care, especially asa pathway to help solve the nation’s maternal healthcrisis and obtain better outcomes for birthing people andinfants, there are significant limitations to its availability.NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES12

of this relationship-based model of personcentered care. Midwifery care often involveslonger office visits and significantly more timewaiting for labor to progress naturally, ratherthan accelerating it with medications andprocedures, so providing adequate paymentcan be a challenge. Across states, Medicaidpayment for CNMs/CMs ranges from 70 percentto 100 percent of physician payment forthe equivalent service.53 However, Medicaidpayment levels vary widely and the averagepayment for CNMs/CMs is just 65 percent of theCNM Medicare fee schedule rate.54Lastly, unnecessarily restrictive practice actsthat, for example, require these independentprofessionals to have physician supervisionor a collaborative practice agreement, limittheir prescriptive authority, or limit theirreimbursement, are associated with reducedmidwifery practice, and thus appear to limitthe access of birthing people to midwifery care.For example, compared with restricted scopeof practice, full scope is associated with morethan twice as many CNMs/CMs per womenof reproductive age and per total births, andfewer counties with no CNMs/CMs.55Policymakers can take many steps to increaseaccess to midwives and the freedom ofmidwives to practice according to the fullNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIESscope of their education and competencies.Although certified nurse-midwives arelicensed to practice and reimbursed byMedicaid in all 50 states, the District ofColumbia, and the U.S. territories, manypractice acts place unnecessary restrictionson these autonomous practitioners. Theseinclude written agreements with physiciansand even requirements for physiciansupervision (Figure 1).Among the nine states that currentlyregulate certified midwive

of midwifery care in improving maternal and infant outcomes, the interest of birthing people in midwifery care, and the current availability of, and access to, midwifery services in the United States. We also provide recommendations for key decisionmakers in public and private sectors to help support and increase access to midwifery care.

Our maternity care practitioners represent “partners” in the truest sense of the word, providing quality care that is accessible, effective and efficient. Our Maternity Quality Care Plus incentive program is d

15 STPS FOR MATITY: QUALITY FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF PEOPLE WHO USE MATERNITY SERVICES 15 STPS FOR MATITY: QUALITY FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF PEOPLE WHO USE MATERNITY SERVICES 7 2. GETTING STARTED WITH THE 15 STEPS FOR MATERNITY The Maternity Voices Partnership Service User Chair gathers users/ user representatives, if possible, including partners, family members

The International Childbirth Education Association (ICEA) maintains that family centered maternity care is the foundation on which normal physiologic maternity care resides. Further, family-centered maternity care may be carried out in any birth setting: home, birth center, hos

to go [23, 24], particularly in maternity care [25–28]. There is a limited understanding of the evidence that is (and is not) translated into maternity care, the associated reasons and how population health can be bolstered via evidence-based maternity care [25]. This warrants concern for (at least) three k

NATIONAL GUIDANCE ON COLLABORATIVE MATERNITY CARE Contents NATIONAL HEALTH AND MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL v Boxes Box 1.1 Definition of maternity care collaboration 7 Box 1.2 Principles of maternity care collaboration 7 Box 1.3 Terminology used in the Guidance

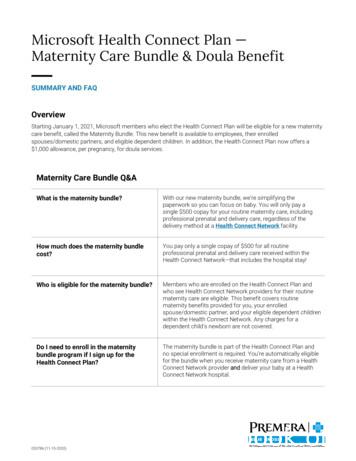

Maternity Care Bundle & Doula Benefit SUMMARY AND FAQ Overview Starting January 1, 2021, Microsoft members who elect the Health Connect Plan will be eligible for a new maternity care benefit, called the Maternity Bundle. T

Current Maternity Care Processes Figure 1 illustrates a typical sequence of maternity service delivery activities. Mothers-to-be typically enter the maternity services system after an initial consultation and recommen-dation from their general practitioners. A

Maternity Care in North West London has been reconfigured under the Shaping a Healthier Future programme. Ealing Hospital's Maternity Unit closed in July 2015 and it was expected that an additional 600 women from Ealing will give birth at Hillingdon Hospital's Maternity Unit in the following year.