Review Of Seeing Like A State - Grasping Reality By

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMReviewsCreated: 99-03-15Last Modified: 99-03-18Go to Brad DeLong's Homehttp://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPageGo115 capturesDEC MAR APR26Teaching Writing 3CareerJun 00 - Politics26 Mar 14 Book Reviews Information Economy Economists Multimedia Students Fine Print Other2012 My 2014Jobs 2015Forests, Trees, and IntellectualRoots.J. Bradford berkeley.eduJames Scott (1998), Seeing Like a State:How Certain Schemes to Improve theHuman Condition Have Failed (NewHaven: Yale University Press:0300070160).I. IntroductionThere is a lot that is excellent in James Scott's Seeing Likea State.On one level, it is an extraordinary well-written and wellargued tour through the various forms of damage thathave been done in the twentieth century by centrallyplanned social-engineering projects--by what James Scottcalls "high modernism" and the attempt to use highmodernist principles and practices to build utopia. Assuch, every economist who reads it will see it as markingthe final stage in the intellectual struggle that the Austriantradition has long waged against apostles of centralplanning. Heaven knows that I am no Austrian--I am aliberal Keynesian and a social democrat--but withineconomics even liberal Keynesian social democratsacknowledge that the Austrians won victory in theirintellectual debate with the central planners long ago.This book marks the final stage because it shows //www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 1 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMspread of what every economist would see as "Austrianideas" into political science, sociology, and anthropologyas well.No one can finish reading Scott without believing--asAustrians have argued for three-quarters of a century--thatcentrally-planned social-engineering is not an appropriatemechanism for building a better society.But on a second level, it is an act of displacement.Friedrich Hayek, after all, won the Nobel Prize inEconomic Science for making many of Scott's keyarguments: that the bureaucratic planner with a map doesnot know best, and can not move humans and their livesaround the territory as if on a chessboard to create utopia;that the local, practical knowledge possessed by theperson-on-the-spot is important; that the locus of decisionmaking must remain with those who have the craft tounderstand the situation; that any system that functions atall must create and maintain a space for those on the spotto use their local, practical knowledge (even if thehierarchs of the system pretend not to notice thisflexibility). These key arguments are well known: they arethe core of the Austrian economists' critique of centralplanning.From one perspective, this is a compliment to theAustrians: their arguments are powerful and applicable,and it is striking that others looking at the same problemcome up with their conclusions. From another perspective,this is odd: we all think better thoughts when we explicitlyrecognize and acknowledge our intellectual roots.II. Seeing the ForestScott's Seeing Like a State begins with a ride througheighteenth- and nineteenth-century German forestry. InGermany, "scientific" forestry led to the planting andharvesting of large monocrop forests of Norway spruceand Scotch pine. And for the first century or so thepockets of forest-owners bulged as more and morevaluable trees were harvested from the increasinglyordered and managed forests.But the foresters did not understand the ecological webthat they were trying to manage: Clearing of underbrushto make it easier for lumberjacks to move about in theforest "greatly reduced the diversity of insect, mammal,and bird populations" (p. 20); the absence of animals andthe absence of rotting wood on the forest floor greatlyreduced the replenishment of the soil with nutrients. Inplaces where all the trees are mature, of the same age andof the same species, storms can wreak catastrophe as p://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 2 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMknock each other over like bowling pins. Pests andparasites that attack a particular species find a bonanzaand grow to epidemic proportions when they find amonocrop forest.The result was what Germans call Waldsterben--the deathof the forest, as it becomes both a pale shadow of itsprevious ecological richness and an inefficient source oftimber for human use.Why does Scott begin with such a tale of pseudo-scientifichubris in Germany before 1900? After all, he could havelooked across the North Sea at England a century or sobefore, where the systematic experimentation and analysisof the agricultural revolution had led to a quitesophisticated understanding of what patterns of croprotation, nutrient addition, and farm diversity couldproduce maximum sustainable and maximum economicyield. Why not tell a story about how human communitiessuccessfully managed a sustainable agriculture, ratherthan one about how human communities unsuccessfullycreated an unsustainable forestry?Scott opens with his tale of German foresters because heargues that this type of interaction--people in rooms linedwith green silk lay out complicated plans, which are thenapproved by the politically powerful, implemented withno regard for local conditions or local knowledge, andwind up as disasters--is typical of how states have dealtwith problems and people in the twentieth century. Whenstates--bureaucrats in offices in the capital--try to assesswhat is going on, they use maps: maps of territory, oftenwith the demarcations between plots or regions made tobe straight lines that meet at right angles, whether or notsuch lines of demarcation make any sense for those wholive on the ground; maps of people--the lists of names andrelationships that allow the state to track those from whomit will claim "obligations"--maps of laws, that fit humanrelationships of gift, exchange, and indebtedness that haveboth economic and emotional facets into a few welldefined categories of right and wrong.But the map is never the territory. Scott reports that thefirst railroad from Paris to Strasbourg ran straight eastfrom Paris across the plateau of Brie, far from thepopulated Marne, because the bureaucrat Victor Legranddrew the line so. The consequence was that the railroadwas ruinously expensive because Victor Legrand forgotthat to be useful a railroad has to carry goods andpassengers from where they are to where they or theirowners want them to go--not look like a pretty straightline on a map back in Paris (p. 76). By page 87 the readeris well-prepared to agree with Scott that the map is p://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 3 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMthe territory, and that what the state "sees" is only a verysmall slice of reality.III. The Critique of "High Modernism"However, these discussions of forests and maps are justthe warm-up. Scott's main argument begins on page 87 ashe lets twentieth-century states have it with both barrels.Scott then mounts a vicious, powerful, and effectivefangs-bared critique of what he calls "high modernism":the belief that the bureaucratic planner with a map-whether Le Corbusier designing a city, Vladimir Lenindesigning a planned economy after what he thought heknew of the German war economy, or Julius Nyerere"villagizing" the people of Tanzania--knows best, and canmove humans and their lives around the territory as if on achessboard, and so create utopia. Scott sees the "idea of aroot-and-branch, rational engineering of entire socialorders in creating realizable utopias" as a twentiethcentury idea that has gone far to making this century adystopia.A. High Modernism in Urban PlanningScott's critique of "high modernism" as a mode of urbanplanning focuses on Brazil's capital, the now more thanone generation-old planned city of Brasilia. As far as theypossibly could, the designers of Brasilia tried to achievethe spatial segregation of different aspects of life--housingin a different place from work, recreation, traffic, publicadministration in different districts as well--as highmodernist guru Le Corbusier had commanded.The consequences of the plan--as far as it could be carriedout--are insane. As Scott writes of the central square ofBrasilia:.what a square! The vast, monumental Plazaof the Three Powers, flanked by theEsplanade of the Ministries, is of such a scaleas to dwarf even a military parade. Incomparison, [Beijing's] Tien-an-Men Squareand [Moscow's] Red Square [both of whichare too large a scale for the foot and vehicletraffic through them on a normal day] arepositively cozy and intimate. If one were toarrange to meet a friend there, it would berather like trying to meet someone in themiddle of the Gobi desert. And if one didmeet up with one's friend, there would benothing to do. This plaza is a http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 4 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMcenter for the state; the only activity that goeson around it is the work of the ministries. (p.121)Scott draws heavily on the excellent work of Jane Jacobsto criticize this planned, surprise-free, every-apartmentbuilding-looks-the-same high-modernist order of preplanned Brasilia. Jacobs argued that rigid spatialsegregation of functions made for visual regularity fromthe bird's-eye view of the architect but made the city damnhard to live in. By contrast, it is the mingling of residenceswith shopping areas and workplaces that makes an urbanneighborhood interesting--and livable. And this urbandiversity of uses cannot be planned by the high-modernistarchitect. At best it can be planned for--by the governmentproviding a framework and infrastructure for urbandevelopment instead of specifying land use down to thelast square centimeter.As Scott argues, even planners who recognize diversitywill never plan it. You cannot spend your life at the office,and bureaucratic budgets are limited. Thus:.the logic of uniformity and regimentation iswell-nigh inexorable [in comprehensive urbanplanning]. Cost effectiveness contributes tothis tendency. Just as it saves a prison troubleand money if all prisoners wear uniforms ofthe same material, color, and size, everyconcession to diversity [in the urban plan] islikely to entail a corresponding increase inadministrative time and budgetary costs.[T]he one-size-fits-all solution is likely toprevail (pp. 141-2).B. High Modernism, the Revolutionary Party, and thePlanned EconomyScott's second example of "high modernism" run amuck atenormous human cost is Lenin's attempt to design therevolution, the society, and the economy of Russia.To Lenin, "the party is to the working class as intelligenceis to brute force, deliberation to confusion, a manager to aworker, a teacher to a student, an administrator to asubordinate, a professional to an amateur, an army to amob, or a scientist to a layman" (p. 149): the vanguardparty possesses the scientific theory--Marxism--thatallows it to plan the revolution. And the transmission ofinformation and commands must be one-way only: theonly thing that the party could learn from the workerswould be petty-bourgeois ideologies that would infect it /www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 5 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMwith a disease (p. 155).After the revolution, according to Lenin, utopia will bebuilt through use of the state. Quoting State andRevolution, Scott draws out of Lenin's ideas for economyand society the image of a gigantic ocean liner, captainedby the party's politburo:The revolution ousts the bourgeoisie from the[controlling] bridge of the "ocean liner" [ofsociety], installs the vanguard party, and setsa new course, but the jobs of the vast crew areunchanged. Lenin's picture of the technicalstructure. is entirely static. The forms ofproduction are either set or. [their] changescannot require skills of a different order (p.162).Or as Lenin put it in his "Immediate Tasks of the SovietGovernment:.large-scale machine industry. thefoundation of socialism. calls for absoluteand strict unity of will, which directs the jointlabors of hundreds, thousands, and tens ofthousands of people. But how can strictunity of will be ensured? By thousandssubordinating their will to the will of one.We must learn to combat the public-meetingdemocracy of the working people--turbulent,surging, overflowing its banks like a springflood--with iron discipline while at work,unquestioning obedience to the will of asingle person, the Soviet leader, while at work(p. 163).And the end of the process that Lenin sees in State andRevolution--an end that Scott calls "chillingly Orwellian"-no one will be able to move an inch from their assignedplace:Escape from this national accounting willinevitably become more difficult. and willprobably be accompanied by such swift andsevere punishment. that very soon thenecessity of observing the simple,fundamental rules of social life in commonwill have become a habit (p. 163).Scott contrasts the communism of Rosa Luxemburg andAlexandra Kollontai to that of Lenin. Luxemburg did seethat when one was exploring new social territory: "onlyexperience is capable of correcting and opening newways. Only unobstructed, effervescing life falls into www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 6 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMthousand new forms and improvisations, brings to lightcreative force, itself corrects all mistaken attempts" (p.174). And Luxemburg did see that Lenin's "socialism.decreed from behind a few official desks by a dozenintellectuals" was headed for complete disaster:.with the suppression of political life in theland as a whole, life in the soviets must alsobecome crippled. Without general elections,without unrestricted freedom of the press andassembly, without a free struggle of opinion,life dies out in every public institution.Public life gradually falls asleep. an elite ofthe working class is invited to applaud thespeeches of the leaders, and to approveproposed resolutions unanimously--at bottomthen, a clique. a dictatorship. (p. 174).We all know the economic and human consequences ofLenin's centrally-planned soviet vision. Scott writes thatthe high estimates--20 million or so--of deaths from thecollectivization of agriculture have "if anything, gainedmore credibility as new archival evidence has becomeavailable" (p. 202). Yet he notes that from Stalin'sperspective collectivization was certainly a success:Collectivization proved a rough-and-readyinstrument for the twin goals of traditionalstatecraft: appropriation and political control.Although the Soviet kolkhoz may have failedbadly [at efficient produciton], it served wellenough as a means whereby the state coulddetermine cropping pattersn, fix real ruralwages, appropriate a large share of whatevergrain was produced, and politicallyemasculate the countryside (p. 203).C. "Villagization" in TanzaniaScott's third major example of destructive high modernismis Julius Nyerere's attempt from 1973 to 1976 to move allthe rural inhabitants of Tanzania into villages. Fivemillion farmers and their families were moved into newlyconstructed villages set up so that the state could easilydeliver social services to (and levy taxes from) thepopulations.Nyerere believed that Tanzanians should live in villages-rather than scattered across the countryside whereagricultural resources were to be found--because:. unless we [live in villages] we shall not /www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 7 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMable to provide ourselves with the things weneed to develop our land and to raise ourstandard of living. We shall not be able to usetractors; we shall not be able to provideschools for our chldren; we shall not be ableto build hospitals, or have clean drinkingwater; it will be quite impossible to startsmall village industries, and instead we shallhave to go on depending on the towns for allour requirements; and if we had a plentifulsupply of electric power we should never beable to connect it up to each isolatedhomestead (p. 230).And what if the farmers did not want to live in villages, ordid not want to grow the crops that Nyerere's bureaucratsback in The House of Peace thought that they shouldgrow? Then: "[i]t may be possible--and sometimesnecessary--to insist on all farmers in a given area growinga certain acreage of a particular crop until they realize thatthis brings them a more secure living, and then do nothave to be forced to grow it" (p. 231).The consequences of Nyerere's policies were predictable.As Scott summarizes:Peasants were. shifted to poor soils on highground. moved to [houses near] all-weatherroads where the land was unfamiliar orunsuitable for the crops. village livingplaced cultivators far from their fields, thusthwarting crop watching and pest control.the concentration of livestock and people.encourag[ed] cholera and livestockepidemics. pastoralists [found that].herding cattle to a single [village] locationwas an unmitigated disaster for rangeconservation and pastoral livelihoods.[Bureaucratic] insistence that they had amonopoly on useful knowledge and that theyimpose this knowledge set the stage fordisaster. (pp. 246-7).The only bright spots were "the Tanzanian state's relativeweaknesses. as well as the Tanzanian peasants' tacticaladvantages, including flight, unofficial production andtrade, smuggling, and foot dragging" which "combined tomake the practice of villagization" less destructive than itmight have been (p. 247).IV. Trees, Forests, and RootsA. Deja /www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 8 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMWell before the middle of the book this non-Austrianliberal-Keynesian economist was--any economist wouldbe--struck by a strong sense of deja vu. Scott'sdeclarations of the importance of the detailed practicalknowledge possessed by the person-on-the-spot--of howsuch knowledge cannot be transmitted up any hierarchy tothose-in-charge in a way to do any good--of how the locusof decision-making must remain with those who have thecraft to understand the situation--of how any system thatfunctions at all must create and maintain a space in whichthere is sufficient flexibility for craftsmen to exercise theirlocal, pratical knowledge (even if the hierarchs of thesystem pretend not to notice this flexibility)--all of thesewill strike any economist as very, very familiar.All of these seem familiar to economists because they arethe points made by Ludwig von Mises (1920) andFriedrich Hayek (1937) and the other Austrian economistsin their pre-World War II debate with socialists over thepossibility of central planning.Hayek's adversaries--Oskar Lange and company--arguedthat a market system had to be inferior to a centrallyplanned system: at the very least, a centrally-plannedeconomy could set up internal decision-makingprocedures that would mimic the market, and the centralplanners could also adjust things to increase social welfareand account for external effects in a way that a marketsystem could never do.Hayek, in response, argued that the functionaries of acentral-planning board could never succeed, because theycould never create both the incentives and the flexibilityfor the people-on-the-spot to use the immense amount ofknowledge about the actual situation that only people-onthe-spot can know.As Hayek argued in his "Impossibility of SocialistCalculation," the enormous amount of dispersedknowledge that individual producers know and act on in amarket economy can never be mobilized by a centralplanner. That a central planner could--that he or she couldever "possess a complete inventory of the amounts andqualities of all the different materials and instruments ofproduction" available to the manager of a single plant--is"a somewhat comic fiction."In Hayek's view, as he wrote in "The Use of Knowledge inSociety," the fundamental economic problem is:.the fact that knowledge of thecircumstances of which we must make usenever exists in concentrated or integratedform, but solely as the dispersed bits ofincomplete and frequently 0505/http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 9 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMknowledge which all the separate individualspossess. It is rather a problem of how tosecure the best use of resources known to anyof the members of society, for ends whoserelative importance only these individualsknow. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem ofthe utilization of knowledge.All of Scott's examples are cases illustrating that thecentrally-planned social-engineering that Scott calls "highmodernism" is definitely not a way to solve thisfundamental economic problem. The bulk of Scott's bookis spent adducing evidence for the critique of centrallyplanned social engineering that had been made byFriedrich Hayek back before World War II.Yet a casual reader of the book would not find anysignificant pointers to the Austrian intellectual tradition-no references to works like "The Impossibility of SocialistCalculation," "The Use of Knowledge in Society," or"Competition as a Discovery Procedure" that are directlyon point for Scott's critique of centrally-planned socialengineering (the only works referred to are The Road toSerfdom and the collection Studies in Philosophy,Economics, and Politics, with no references to theindividual works collected in the volume).B. Where Is Hayek?So how is it that Scott can see the trees and the overallforest so very very well, but does not see his ownintellectual roots?I should note that today almost every single economist-even those who (like me) are profoundly hostile to manyof Hayek's arguments (that government regulation of themoney supply lies at the root of the business cycle, thatpolitical attempts to reduce inequalities in the distributionof income are likely to lead to totalitarianism, that theFederal Reserve should be abolished, that the competitivemarket is the "natural spontaneous order" of humansociety)--agrees that Hayek and his company (includingScott) hit the particular nail that is Scott's central theme,the critique of high-modernist centrally-planned socialengineering, squarely on the head.Scott's Seeing Like a State's index contains no referencesto Ludwig von Mises. It does contain six references toFriedrich Hayek:A favorable reference on page 256 to Hayek forpointing out that a "command economy, ttp://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 10 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMsophisticated and flexible, cannot begin to replacethe myriad, rapid, mutual adjustments offunctioning markets and the price system."A critique in a footnote of Hayek's belief that themarket economy is a spontaneous form of socialorder. Instead, Scott believes, the market economy"had to be imposed by a coercive state in thenineteenth century, as Karl Polanyi hasconvincingly shown." But this is coupled with anadmission that "Hayek's description of thedevelopment of common law" as "I believe,somewhat closer to the mark."An approving reference in a footnote to Hayek'sskepticism about the usefulness of economic theory(p. 427); a reference to the "curious unanimity"between "such right-wing critics of the commandeconomy as Friedrich Hayek and such left-wingcritics of communist authoritarianism as Price PeterKropotkin" who call, in Albert Hirschman's word,for "more 'reverence for life'. less straitjacketing ofthe future. more allowance for the unexpected.less wishful thinking" in economic development(pp. 344-5); and a supporting footnote stating thatHayek--"the darling of those opposed to postwarplanning and the welfare state"--makes the samepoint as Michel Foucault, who said in a lecture thatwas then published in 1991 that: "political economyannounces the unknowability for the sovereign ofthe totality of economic processes and, as aconsequence, the impossibility of an economicsovereignty," and that this was one of the mainpoints of liberal political economy (pp. 101-2, 381).And, finally, a preemptive strike against Hayek inthe introduction: "Put bluntly, my bill of particularsagainst [the high-modernist centrally-planningsocial-engineering] state is by no means a case forpolitically unfettered market coordination as urgedby Friedrich Hayek or Milton Friedman. As weshall see, the conclusions that can be drawn fromthe failures of modern projects of social engineeringare as applicable to market-driven standardizationas they are to bureaucratic homogeneity" (p. 8).The first two references I agree with. Hayek is write incriticizing the inflexibility of the command economy, andScott is right in arguing that the market economy is notthe "natural" form of human social order.The third, fourth, and fifth references seem to me to missthe point: no one reading Hayek should be surprised thathe is skeptical about claims to useful theoreticalknowledge, the unanimity between the left and rightbranches growing out of the anarchist tradition is //www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 11 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PM"curious" but a result of these two branches' commonroots, and the late Foucault (even though correct, and atthe time of his death a serious student of liberal politicaleconomy) is not the expert of choice on liberal politicaleconomy.The sixth reference may be the key. Scott cannot citeEdmund Burke in Seeing Like a State--and much ofScott's book consists of praise for the wisdom embodiedin community practices in a Burkean vein--except as an"apologist. for. power, privilege, and property." AndScott cannot embrace Friedrich Hayek out of the fear thatit will turn his book into a "case for politically-unfetteredmarket coordination." Instead, he believes that hisargument is as much a critique of "market-drivenstandardization" as of "bureaucratic homogeneity."C. Rubber TomatoesHow can market-driven standardization have the sameconsequences as the commands of architects who havenever lived in the cities they design, or as thecollectivization of Soviet agriculture, or as the forced"villagization" of Tanzanian peasants?It is unclear.Scott has a long critique of agricultural extension servicesand agricultural development programs in the third world,and the scorn their "experts" had for the practicalknowledge of the rural peasant (pp. 270-306). But anyAustrian would agree with all of it: the claims of theexperts from the center that they know everything and thepeasant knows nothing about how to grow crops in Ghanais ludicrous.Woven into the critique of agricultural developmentprograms are asides about the destructiveness of DDT, theeffect of sterile hybrid seeds in diminishing the autonomyof the farmer, the vulnerability of American monoculturefarms to pests and epidemics, and the pre-packagedrelatively-tasteless--but overwhelmingly cheap--rubbertomatoes developed to be machine-sprayed and machinepicked. However, people bought (and buy) rubbertomatoes because they are cheap--because relatively littlesocial labor is required to produce them. Overall we havethe "unparalleled agricultural productivity" of theindustrial West, in which the U.S. is a major exporter offood products even though its economy now employsfewer farmers and farm laborers than gardeners 326180505/http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ Articles/reviews/seeing like a state.htmlPage 12 of 16

Review of Seeing Like a State12/16/14, 12:42 PMThe argument that market-driven processes are as harmfulto human freedom as state-led high modernism appearssuddenly at the end of a discussion of the importance ofpractical, local knowledge and expertise. Scott calls thispractical, local knowledge "metis," taking the word fromthe skill traditionally attributed to Odysseus. Takes it to bea counterweight to the type of theoretical or technicalknowledge held by bureaucrats, scientists, and others (pp.309-341). Most such practical knowledge cannot be easilysummarized and simple rules, and much of it remainsimplicit: the devil is in the details.In the middle of this discussion of "metis" we suddenlyread that:The destruction of metis and its replacementby standardized formulas legible only fromthe center is virtually inscribed in theactivities of both the state and large-scalebureaucratic capitalism (p. 335).But when we look around at modern large-scalebureaucratic capitalism, we see what Scott calls "metis"everywhere. Everything from the flick of your wrist sothat the supermarket laser-scanner reads the bar code (tryit some time) to the virtual experience at flying 747's thatairline pilots gain in simulators to knowing when youhave lost your lecture audience and need to back up toknowing when it too risky to drive the moving van overDonner Pass--all of these are forms of metis. Att

Scott's Seeing Like a State begins with a ride through eighteenth- and nineteenth-century German forestry. In Germany, "scientific" forestry led to the planting and harvesting of large monocrop forests of Norway s

Ways of Seeing: Art, Politics, and Modern Perception. Discussion of Berger, Ways of Seeing. Looking at objects/texts: Breuer Chair Jan. 17: Ways of Seeing. Theoretical and Philosophical Approaches. Reading: John Berger, Ways of Seeing. Guillaume Apollinaire, selected poetry from Calligra

Kyle - also a Seeing Eye graduate - their young son, James, her parents, a bunny, and four Seeing Eye dogs - two working, and two retired! The photo shows Siobhan smiling as she sits on her front stoop with her current Seeing Eye dog, a black Labrador retriever named Presley. Siobhan was matched with her first Seeing Eye dog when she was

The Aesthetic Experience with Visual Art "At First Glance . More Seeing-in: Surface Seeing, Design Seeing, and Meaning Seeing in Pictures . visual brain that make man particularly responsive to such qualities. In short, even though scholars, for obvious reasons, distribute their efforts selectively and focus .

Seeing like a state The assumption in PIRLS tests and in wider language policy in South African schools that all children have equal access to a standard language that reflects their ethnolinguistic identity is what Silverstein (2014) refers to as ‘seeing like a state’ because of the assumption that everyone . 4

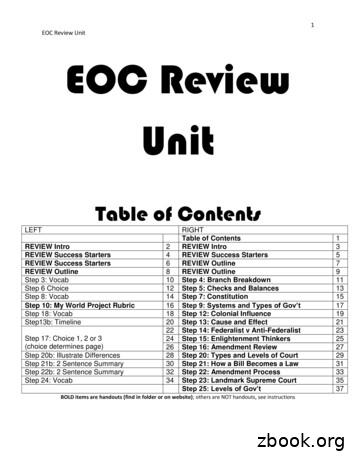

1 EOC Review Unit EOC Review Unit Table of Contents LEFT RIGHT Table of Contents 1 REVIEW Intro 2 REVIEW Intro 3 REVIEW Success Starters 4 REVIEW Success Starters 5 REVIEW Success Starters 6 REVIEW Outline 7 REVIEW Outline 8 REVIEW Outline 9 Step 3: Vocab 10 Step 4: Branch Breakdown 11 Step 6 Choice 12 Step 5: Checks and Balances 13 Step 8: Vocab 14 Step 7: Constitution 15

akuntansi musyarakah (sak no 106) Ayat tentang Musyarakah (Q.S. 39; 29) لًََّز ãَ åِاَ óِ îَخظَْ ó Þَْ ë Þٍجُزَِ ß ا äًَّ àَط لًَّجُرَ íَ åَ îظُِ Ûاَش

Collectively make tawbah to Allāh S so that you may acquire falāḥ [of this world and the Hereafter]. (24:31) The one who repents also becomes the beloved of Allāh S, Âَْ Èِﺑاﻮَّﺘﻟاَّﺐُّ ßُِ çﻪَّٰﻠﻟانَّاِ Verily, Allāh S loves those who are most repenting. (2:22

Seeing Like a State -Thinking like a Hedge Fund: Intangible Assets, Financial Derivatives and Unbundling the State and the Corporation Dick Bryan*, Nigel Douglas*, Mike Rafferty* and Duncan Wigan** Abstract The current debate about internation