Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain And Process . - List

GUIDELINESOccupational Therapy PracticeFramework: Domain and ProcessFourth EditionContentsPreface .1Definitions .1Evolution of This Document .2Vision for This Work .4Introduction .4Occupation and Occupational Science .4OTPF Organization .4Cornerstones of Occupational TherapyPractice .6Domain .6Occupations .7Contexts .9Performance Patterns .12Performance Skills .13Client Factors .15Process .17Overview of the Occupational TherapyProcess .17Evaluation .21Intervention .24Outcomes .26Conclusion .28Tables .29References .68Table 1. Examples of Clients: Persons, Groups,and Populations . 29Table 2. Occupations .30Table 3. Examples of Occupations for Persons,Groups, and Populations .35Table 4. Context: Environmental Factors .36Table 5. Context: Personal Factors .40Table 6. Performance Patterns .41Table 7. Performance Skills for Persons .43Table 8. Performance Skills for Groups .50Table 9. Client Factors .51Table 10. Occupational Therapy Process forPersons, Groups, and Populations .55Table 11. Occupation and ActivityDemands .57PrefaceThe fourth edition of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domainand Process (hereinafter referred to as the OTPF–4), is an official document ofthe American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Intended foroccupational therapy practitioners and students, other health careprofessionals, educators, researchers, payers, policymakers, and consumers,the OTPF–4 presents a summary of interrelated constructs that describeoccupational therapy practice.DefinitionsWithin the OTPF–4, occupational therapy is defined as the therapeutic use ofeveryday life occupations with persons, groups, or populations (i.e., the client)for the purpose of enhancing or enabling participation. Occupational therapypractitioners use their knowledge of the transactional relationship among theclient, the client’s engagement in valuable occupations, and the context todesign occupation-based intervention plans. Occupational therapy servicesare provided for habilitation, rehabilitation, and promotion of health andwellness for clients with disability- and non–disability-related needs. Theseservices include acquisition and preservation of occupational identity forclients who have or are at risk for developing an illness, injury, disease,disorder, condition, impairment, disability, activity limitation, or participationrestriction (AOTA, 2011; see the glossary in Appendix A for additionaldefinitions).When the term occupational therapy practitioners is used in thisdocument, it refers to both occupational therapists and occupational therapyassistants (AOTA, 2015b). Occupational therapists are responsible for allaspects of occupational therapy service delivery and are accountable for thesafety and effectiveness of the occupational therapy service delivery process.AOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENTThe American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms17412410010p1

GUIDELINESTable 12. Types of Occupational TherapyInterventions .59Table 13. Approaches to Intervention .63Table 14. Outcomes .65Exhibit 1. Aspects of the Occupational TherapyDomain .7Exhibit 2. Operationalizing the OccupationalTherapy Process .16Figure 1. Occupational Therapy Domain andProcess .5Authors .72Acknowledgments .73Appendix A. Glossary .74Index .85Occupational therapy assistants deliver occupational therapy services underthe supervision of and in partnership with an occupational therapist (AOTA,2020a).The clients of occupational therapy are typically classified as persons(including those involved in care of a client), groups (collections of individualshaving shared characteristics or a common or shared purpose; e.g., familymembers, workers, students, people with similar interests or occupationalchallenges), and populations (aggregates of people with common attributessuch as contexts, characteristics, or concerns, including health risks; Scaffa& Reitz, 2014). People may also consider themselves as part of a community,such as the Deaf community or the disability community; a community is acollection of populations that is changeable and diverse and includes variouspeople, groups, networks, and organizations (Scaffa, 2019; World Federationof Occupational Therapists [WFOT], 2019). It is important to consider thecommunity or communities with which a client identifies throughout theoccupational therapy process.Whether the client is a person, group, or population, information about theclient’s wants, needs, strengths, contexts, limitations, and occupational risks isgathered, synthesized, and framed from an occupational perspective. ThroughoutCopyright 2020 by the AmericanOccupational Therapy Association.Citation: American Occupational TherapyAssociation. (2020). Occupational therapypractice framework: Domain and process(4th ed.). American Journal of OccupationalTherapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001ISBN: 978-1-56900-488-3For permissions inquiries, visit https://www.copyright.com.the OTPF–4, the term client is used broadly to refer to persons, groups, andpopulations unless otherwise specified. In the OTPF–4, “group” as a client is distinctfrom “group” as an intervention approach. For examples of clients, see Table 1 (alltables are placed together at the end of this document). The glossary in AppendixA provides definitions of other terms used in this document.Evolution of This DocumentThe Occupational Therapy Practice Framework was originally developed toarticulate occupational therapy’s distinct perspective and contribution topromoting the health and participation of persons, groups, and populationsthrough engagement in occupation. The first edition of the OTPF emergedfrom an examination of documents related to the Occupational Therapy ProductOutput Reporting System and Uniform Terminology for Reporting OccupationalTherapy Services (AOTA, 1979). Originally a document that responded to a federalrequirement to develop a uniform reporting system, this text gradually shifted todescribing and outlining the domains of concern of occupational therapy.The second edition of Uniform Terminology for Occupational Therapy(AOTA, 1989) was adopted by the AOTA Representative Assembly (RA) andpublished in 1989. The document focused on delineating and defining onlythe occupational performance areas and occupational performance componentsthat are addressed in occupational therapy direct services. The third and finaledition of Uniform Terminology for Occupational Therapy (UT–III; AOTA, 1994)was adopted by the RA in 1994 and was “expanded to reflect current practiceand to incorporate contextual aspects of performance” (p. 1047). Each revision2The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/termsAOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENT7412410010p2

GUIDELINESreflected changes in practice and provided consistentnThe terms occupation and activity are more clearlyndefined.For occupations, the definition of sexual activity as anterminology for use by the profession.In fall 1998, the AOTA Commission on Practice (COP)embarked on the journey that culminated in theactivity of daily living is revised, health management isOccupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domainadded as a general occupation category, and intimateand Process (AOTA, 2002a). At that time, AOTA alsopartner is added in the social participation categorypublished The Guide to Occupational Therapy Practice(see Table 2).for the profession. Using this document and the feedbackThe contexts and environments aspect of theoccupational therapy domain is changed to context onreceived during the review process for the UT–III, the COPthe basis of the World Health Organization (WHO; 2008)(Moyers, 1999), which outlined contemporary practicenproceeded to develop a document that more fullytaxonomy from the International Classification ofarticulated occupational therapy.The OTPF is an ever-evolving document. As anFunctioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in an effortofficial AOTA document, it is reviewed on a 5-yearTable 4).For the client factors category of body functions,cycle for usefulness and the potential need for furtherto adopt standard, well-accepted definitions (seenrefinements or changes. During the review period, the COPgender identity is now included under “experience ofcollects feedback from AOTA members, scholars, authors,self and time,” the definition of psychosocial ispractitioners, AOTA volunteer leadership and staff, andexpanded to match the ICF description, andother stakeholders. The revision process ensures that theOTPF maintains its integrity while responding to internal andinteroception is added under sensory functions.ntasks” has been changed to “interventions to supportexternal influences that should be reflected in emergingconcepts and advances in occupational therapy.The OTPF was first revised and approved by the RA inFor types of intervention, “preparatory methods andnoccupations” (see Table 12).For outcomes, transitions and discontinuation are2008. Changes to the document included refinement of thediscussed as conclusions to occupational therapywriting and the addition of emerging concepts and changesservices, and patient-reported outcomes arein occupational therapy. The rationale for specific changesaddressed (see Table 14).can be found in Table 11 of the OTPF–2 (AOTA, 2008,npp. 665–667).In 2012, the process of review and revision of theOTPF was initiated again, and several changes weremade. The rationale for specific changes can be foundon page S2 of the OTPF–3 (AOTA, 2014).In 2018, the process to revise the OTPF began again.After member review and feedback, several modificationswere made and are reflected in this document:nperformance skills) Table 8. Performance Skills for Groups(includes examples of the impact of ineffectiveindividual performance skills on groupThe focus on group and population clients isincreased, and examples are provided for both.nncollective outcome) Table 10. Occupational Therapy Process forCornerstones of occupational therapy practice areidentified and described as foundational to thesuccess of occupational therapy practitioners.Occupational science is more explicitly describedFive new tables are added to expand on and clarifyconcepts: Table 1. Examples of Clients: Persons, Groups,and Populations Table 3. Examples of Occupations for Persons,Groups, and Populations Table 7. Performance Skills for Persons (includesexamples of effective and ineffectivePersons, Groups, and Populations.nand defined.AOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENTThe American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/termsThroughout, the use of OTPF rather than Frameworkacknowledges the current requirements for a unique37412410010p3

GUIDELINESnidentifier to maximize digital discoverability and topromote brevity in social media communications. Itstudents, communication with the public andpolicymakers, and provision of language that can shapealso reflects the longstanding use of the acronym inand be shaped by research.academic teaching and clinical practice.Figure 1 has been revised to provide a simplifiedOccupation and Occupational Sciencevisual depiction of the domain and process ofoccupational therapy.Embedded in this document is the occupational therapyprofession’s core belief in the positive relationshipVision for This Workbetween occupation and health and its view of people asoccupational beings. Occupational therapy practiceAlthough this edition of the OTPF represents the latest inemphasizes the occupational nature of humans and thethe profession’s efforts to clearly articulate theoccupational therapy domain and process, it builds on aimportance of occupational identity (Unruh, 2004) tohealthful, productive, and satisfying living. As Hooper andset of values that the profession has held since itsfounding in 1917. The original vision had at its center aWood (2019) stated,profound belief in the value of therapeutic occupations asA core philosophical assumption of the profession, therefore, is that byvirtue of our biological endowment, people of all ages and abilitiesrequire occupation to grow and thrive; in pursuing occupation, humansexpress the totality of their being, a mind–body–spirit union. Becausehuman existence could not otherwise be, humankind is, in essence,occupational by nature. (p. 46)a way to remediate illness and maintain health (Slagle,1924). The founders emphasized the importance ofestablishing a therapeutic relationship with each clientand designing a treatment plan based on knowledgeabout the client’s environment, values, goals, and desires(Meyer, 1922). They advocated for scientific practicebased on systematic observation and treatment (Dunton,1934). Paraphrased using today’s lexicon, the foundersproposed a vision that was occupation based, clientcentered, contextual, and evidence based—the visionarticulated in the OTPF–4.IntroductionThe purpose of a framework is to provide a structure orOccupational science is important to the practice ofoccupational therapy and “provides a way of thinking thatenables an understanding of occupation, the occupationalnature of humans, the relationship between occupation,health and well-being, and the influences that shapeoccupation” (WFOT, 2012b, p. 2). Many of its concepts areemphasized throughout the OTPF–4, includingoccupational justice and injustice, identity, time use,satisfaction, engagement, and performance.OTPF OrganizationThe OTPF–4 is divided into two major sections: (1) thedomain, which outlines the profession’s purview and thebase on which to build a system or a concept(“Framework,” 2020). The OTPF describes the centralareas in which its members have an established bodyconcepts that ground occupational therapy practice andbuilds a common understanding of the basic tenets andof knowledge and expertise, and (2) the process,which describes the actions practitioners take whenvision of the profession. The OTPF–4 does not serve as ataxonomy, theory, or model of occupational therapy. Byproviding services that are client centered andfocused on engagement in occupations. Thedesign, the OTPF–4 must be used to guide occupationalprofession’s understanding of the domain and processtherapy practice in conjunction with the knowledge andevidence relevant to occupation and occupationalof occupational therapy guides practitioners as theyseek to support clients’ participation in daily living,therapy within the identified areas of practice and with theappropriate clients. In addition, the OTPF–4 is intendedwhich results from the dynamic intersection of clients,their desired engagements, and their contextsto be a valuable tool in the academic preparation of(including environmental and personal factors;4The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/termsAOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENT7412410010p4

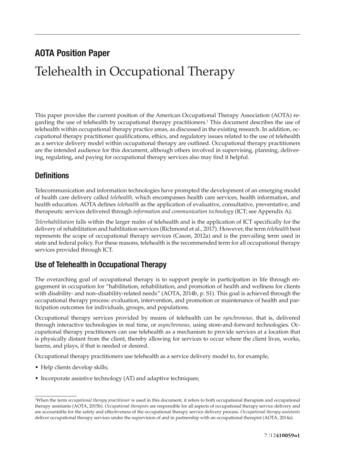

GUIDELINESFigure 1. Occupational Therapy Domain and ProcessD OM A I NCt t ernPaEvaluationSkioPe r fllsChristiansen & Baum, 1997; Christiansen et al., 2005;nrnamWell-being—“a general term encompassing the totaluniverse of human life domains, including physical,Law et al., 2005).“Achieving health, well-being, and participation in lifemental, and social aspects, that make up what can bethrough engagement in occupation” is the overarchingstatement that describes the domain and process ofceClientmcetsPROCESSorantcomesOuPe r fAchieving health,well-being, andparticipation in lifethrough engagementin occupation.texFacInterventionsrsontoOc c up at ionsncalled a ‘good life’” (WHO, 2006, p. 211).Participation—“involvement in a life situation” (WHO,occupational therapy in its fullest sense. This statement2008, p. 10). Participation occurs naturally when clientsacknowledges the profession’s belief that activeare actively involved in carrying out occupations or dailyengagement in occupation promotes, facilitates,life activities they find purposeful and meaningful. Moresupports, and maintains health and participation. Thesespecific outcomes of occupational therapy interventioninterrelated concepts includenare multidimensional and support the end result ofHealth—“a state of complete physical, mental,and social well-being, and not merely theabsence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 2006,participation.np. 1).AOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENTThe American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/termsEngagement in occupation—performance ofoccupations as the result of choice, motivation, andmeaning within a supportive context (including57412410010p5

GUIDELINESenvironmental and personal factors). Engagementincludes objective and subjective aspects of clients’Occupational therapy cornerstones provide afundamental foundation for practitioners from which toexperiences and involves the transactional interactionview clients and their occupations and facilitate theof the mind, body, and spirit. Occupational therapyintervention focuses on creating or facilitatingoccupational therapy process. Practitioners develop thecornerstones over time through education, mentorship,opportunities to engage in occupations that lead toparticipation in desired life situations (AOTA, 2008).and experience. In addition, the cornerstones are everevolving, reflecting developments in occupational therapyAlthough the domain and process are describedseparately, in actuality they are linked inextricably in atransactional relationship. The aspects that constitutethe domain and those that constitute the process exist inconstant interaction with one another during the delivery ofoccupational therapy services. Figure 1 representspractice and occupational science.Many contributors influence each cornerstone. Likethe cornerstones, the contributors are complementaryand interact to provide a foundation for practitioners.The contributors include, but are not limited to, thefollowing:aspects of the domain and process and the overarchingnClient-centered practicegoal of the profession as achieving health, well-being, andparticipation in life through engagement in occupation.nnClinical and professional reasoningCompetencies for practiceAlthough the figure illustrates these two elements indistinct spaces, in reality the domain and process interactnCultural humilitynin complex and dynamic ways as described throughoutthis document. The nature of the interactions isnEthicsEvidence-informed practiceimpossible to capture in a static one-dimensional image.nInter- and intraprofessional collaborationsLeadershipnLifelong learningCornerstones of Occupational Therapy PracticenThe transactional relationship between the domain andnMicro and macro systems knowledgeOccupation-based practiceprocess is facilitated by the occupational therapynpractitioner. Occupational therapy practitioners havedistinct knowledge, skills, and qualities that contribute to thenProfessionalismProfessional advocacynSelf-advocacysuccess of the occupational therapy process, described inthis document as “cornerstones.” A cornerstone can benSelf-reflectionTheory-based practice.nndefined as something of great importance on whicheverything else depends (“Cornerstone,” n.d.), and thefollowing cornerstones of occupational therapy helpdistinguish it from other professions:nCore values and beliefs rooted in occupation (Cohn,2019; Hinojosa et al., 2017)nKnowledge of and expertise in the therapeutic use ofoccupation (Gillen, 2013; Gillen et al., 2019)nProfessional behaviors and dispositions (AOTAn2015a, 2015c)Therapeutic use of self (AOTA, 2015c; Taylor, 2020).DomainExhibit 1 identifies the aspects of the occupationaltherapy domain: occupations, contexts, performancepatterns, performance skills, and client factors. Allaspects of the domain have a dynamic interrelatedness.All aspects are of equal value and together interact toaffect occupational identity, health, well-being, andparticipation in life.Occupational therapists are skilled in evaluating allThese cornerstones are not hierarchical; instead, eachaspects of the domain, the interrelationships among theaspects, and the client within context. Occupationalconcept influences the others.therapy practitioners recognize the importance and6The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/termsAOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENT7412410010p6

GUIDELINESExhibit 1. Aspects of the Occupational Therapy DomainAll aspects of the occupational therapy domain transact to support engagement, participation, and health. This exhibit does not implya hierarchy.OccupationsActivities of daily living (ADLs)Instrumental activities of dailyliving (IADLs)Health managementRest and sleepEducationWorkPlayLeisureSocial talfactorsPersonal Motor skillsProcess skillsSocial interaction skillsClient FactorsValues, beliefs,and spiritualityBody functionsBody structuresimpact of the mind–body–spirit connection onengagement and participation in daily life. Knowledge ofto a specific client’s engagement or context (Schell et al.,2019) and, therefore, can be selected and designed tothe transactional relationship and the significance ofmeaningful and productive occupations forms the basis forenhance occupational engagement by supporting thethe use of occupations as both the means and the endspatterns. Both occupations and activities are used asof interventions (Trombly, 1995). This knowledge setsoccupational therapy apart as a distinct and valuableinterventions by practitioners. For example, a practitionerservice (Hildenbrand & Lamb, 2013) for which a focus onthe whole is considered stronger than a focus on isolatedintervention to address fine motor skills with the ultimateaspects of human functioning.The discussion that follows provides a briefpreparing a favorite meal. Participation in occupations isexplanation of each aspect of the domain. Tables includedat the end of the document provide additionaldescriptions and definitions of terms.OccupationsOccupations are central to a client’s (person’s, group’s, orpopulation’s) health, identity, and sense of competenceand have particular meaning and value to that client. “Inoccupational therapy, occupations refer to the everydayactivities that people do as individuals, in families, and withcommunities to occupy time and bring meaning andpurpose to life. Occupations include things peopleneed to, want to and are expected to do” (WFOT, 2012a,development of performance skills and performancemay use the activity of chopping vegetables during angoal of improving motor skills for the occupation ofconsidered both the means and the end in theoccupational therapy process.Occupations occur in contexts and are influenced bythe interplay among performance patterns, performanceskills, and client factors. Occupations occur over time;have purpose, meaning, and perceived utility to the client;and can be observed by others (e.g., preparing a meal) orbe known only to the person involved (e.g., learningthrough reading a textbook). Occupations can involve theexecution of multiple activities for completion and canresult in various outcomes.The OTPF–4 identifies a broad range of occupationscategorized as activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumentalpara. 2).In the OTPF–4, the term occupation denotesactivities of daily living (IADLs), health management, restpersonalized and meaningful engagement in daily lifeevents by a specific client. Conversely, the term activityparticipation (Table 2). Within each of these nine broaddenotes a form of action that is objective and not relatedexample, the broad category of IADLs has specificand sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and socialcategories of occupation are many specific occupations. ForAOTA OFFICIAL DOCUMENTThe American Journal of Occupational Therapy, August 2020, Vol. 74, Suppl. 2Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 09/22/2020 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms77412410010p7

GUIDELINESoccupations that include grocery shopping and moneymanagement.When occupational therapy practitioners work withclients, they identify the types of occupations clientsengage in individually or with others. Differences amongBecause occupational performance does not exist in avacuum, context must always be considered. For example,for a client who lives in food desert, lack of access to agrocery store may limit their ability to have balance in theirperformance of IADLs such as cooking and groceryand multidimensional. The client’s perspective on how anshopping or to follow medical advice from health careprofessionals on health management and preparation ofoccupation is categorized varies depending on thatnutritious meals. For this client, the limitation is not caused byclient’s needs, interests, and contexts. Moreover, valuesimpaired client factors or performance skills but rather isshaped by the context in which the client functions. Thisclients and the occupations they engage in are complexattached to occupations are dependent on cultural andFor example, one person may perceive gardening ascontext may include policies that resulted in the decline ofcommercial properties in the area, a socioeconomic statusleisure, whereas another person, who relies on the foodthat does not enable the client to live in an area with accessproduced from that garden to feed their family orto a grocery store, and a social environment in which lack ofaccess to fresh food is weighed as less important than thesociopolitical determinants (Wilcock & Townsend, 2019).community, may perceive it as work. Additional examplesof occupations for persons, groups, and populations canbe found in Table 3.The ways in which clients prioritize engagement inselected occupations may vary at different times. Forexample, clients in a community psychiatric rehabilitationsetting may prioritize registering to vote during an electionseason and food preparation during holidays. The uniquefeatures of occupations are noted and analyzed byoccupational therapy practitioners, who consider allcomponents of the engagement and use them effectivelyas both a therapeutic tool and a way to achieve thetargeted outcomes of intervention.The extent to which a client is engaged in a particularoccupation is also important. Occupational therapypractitioners assess the client’s ability to engage insocial supports the community provides.Occupational therapy practitioners recognize thathealth is supported and maintained when clients are ableto engage in home, school, workplace, and communitylife. Thus, practitioners are concerned not only withoccupations but also with the variety of factors that disruptor empower those occupations and influence clients’engagement and participation in positive healthpromoting occupations (Wilcock & Townsend, 2019).Although engagement in occupations is generallyconsidered a positive outcome of the occupational therapyprocess, it is important to consider that a client’s historymight include negative, traumatic, or unhealthyoccupational participation (Robinson Johnson & Dickie,2019). For example, a person who has experienced aoccupational performance, defined as theaccomplishment of the selected occupation resulting fromtraumatic sexual encounter might negatively perceive andthe dynamic transaction among the client, their contexts,eating disorder might engage in eating in a maladaptiveand the occupation. Occupations can contribute to a wellbalanced and fully functional lifestyle or to a lifestyle that isway, deterring health management and physical health.In addition, some occupations that are meaningful to aout of balance and characterized by occupationaldysfunction. For example, excessive work withoutclient might also hinder performance in other occupationssufficient regard for other aspects of life, such as slee

concepts that ground occupational therapy practice and builds a common understanding of the basic tenets and visionoftheprofession.TheOTPF-4doesnotserveasa taxonomy, theory, or model of occupational therapy. By design, the OTPF-4 must be used to guide occupational therapy practice in conjunction with the knowledge and

(2008). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (2nd ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 625-683. American Occupational Therapy Association. (2013). Guidelines for Documentation of Occupational Therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67 (6), S32-S38. American Physical Therapy Association. (2009).

Occupational Therapy Occupational Therapy Information 29 Occupational Therapy Programs 30 Occupational Therapy Articulation Agreements 31 Occupational Therapy Prerequisites 33 Physical Therapy Physical Therapy Information 35 Physical Therapy Programs and Prerequisites 36 Physical Therapy Articulation Agreements 37 Physical Therapy vs .

1When the term occupational therapy practitioner is used in this document, it refers to both occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants (AOTA, 2015b). Occupational therapists are responsible for all aspects of occupational therapy service delivery and are accountable for the safety and effectiveness of the occupational therapy .

therapist or an occupational therapy assistant. (6) "Occupational therapy assistant" means a person licensed by the board as an occupational therapy assistant who assists in the practice of occupational therapy under the general supervision of an occupational therapist. Acts 1999, 76th Leg., ch. 388, Sec. 1, eff. Sept. 1, 1999. Sec. 454.003.

Both the Occupational Therapy Assistant program and Occupational Therapy Doctorate programs are housed in the Occupational Therapy Department. The Chair of the Occupational Therapy Department is Dr. M. Tracy Morrison, OTD, OTR/L who also serves as the Director of the Occupational Therapy Doctorate Program.

Documentation of occupational therapy services is necessary whenever professional services are provided to a client. Occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants1 determine the appropriate type of documentation structure and then record the services provided within their scope of practice. This document, based on the Occupational .File Size: 540KBPage Count: 9Explore furtherDocumentation & Reimbursement - AOTAwww.aota.orgNEW OT Evaluation and Reevaluation - AOTA Guidelinestherapylog.typepad.comWriting progress notes in occupational therapy jobs .www.aureusmedical.comDocumentation & Data Collection For Pediatric Occupational .www.toolstogrowot.comSOAP Note and Documentation Templates & Examples Seniors .seniorsflourish.comRecommended to you b

Created by the American Occupational Therapy Association- The first edition: 2002 The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, 3rd Edition: 2014 Evolution of The OT Practice Framework What we do (Domain)&

Accounting for Nature: A Natural Capital Account of the RSPB’s estate in England 77. Puffin by Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) 8. Humans depend on nature, not only for the provision of drinking water and food production, but also through the inspiring landscapes and amazing wildlife spectacles that enrich our lives. It is increasingly understood that protecting and enhancing the natural .