O Udans Gold Boom Is Changing Labour Relations In Lue Ile State

rift valley institute briefing paper March 2020 How Sudan’s gold boom is changing labour relations in Blue Nile state by Mohamed Salah and Enrico Ille Sudan’s Blue Nile state, which borders Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz region on its eastern side, and South Sudan’s Upper Nile region on its south-west frontier, has a long history of small-scale artisanal gold mining. Gold is found in the region’s hills and in the alluvial planes south of the Blue Nile. In Blue Nile, artisanal gold mining has historically been a communal or household activity—an additional means of income generation to supplement agriculture. However, a gold-rush in Sudan which began around a decade ago and intensified after the secession of South Sudan in 2011, has begun to change the relationship that communities in Blue Nile have with gold mining. r de lue B SENNAR Nil e SUDAN Damazin Damazin Tadamon Roseiris Roseiris Roseiris Dam Wad Al-Mahi Do Roseires Roseiris Reservoir l eib Inges sana Bout Belguwa Menza Almahal Maganza H i l l s Bao Guba Bulang Bakori BLUE NILE Qeissan Baw Qeissan Kurmuk NORTHERN UPPER NILE Kurmuk Ah m BENI SHANGUL-GUMUZ Sherkole Menge ETHIOPIA ar Assosa SOUTH SUDAN Yab u Gold markets—where gold is extracted from ore brought from the mines and sold— have become a central gathering point for different actors in the sector. These markets have brought significant changes to labour relations in the area: for instance, they have provided a new source of income for women and children. But gold extraction has also introduced new forms of damage to environment and health, and seems, overall, to maintain pre-existing socioeconomic hierarchies. N Din s Rift Valley Institute 2020 www.riftvalley.net Boundaries and names shown do not imply endorsement by the RVI or any other body MAPgrafix 2020 NILE Baw OROMIA 0 km 25 International boundary Nominal boundary SPLM/A-N presence State/region Locality Gold market Refugee camp State capital Main town Other town Selected road/track River/lake Base map data source: OpenStreetMap Expanding gold extraction Sudan’s country-wide gold-rush has expanded national interest in gold extraction into regions that had only local small-scale mining before, including Blue Nile. The state was previously the focus for mechanised agriculture after the construction of the Roseiris Dam in the 1960s and its heightening in the 2000s. Blue Nile later became embroiled in the conflict between the central government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North (SPLM-N), albeit now in a precarious standstill. In the meantime, gold mining has increased in the state. What was previously an activity limited to local residents now attracts miners from across the country (principally Darfur and Kordofan), and also from South Sudan and Ethiopia. Others have arrived from as far afield as West Africa. In the 2000s, North

and West Africa became attractive destinations for Sudanese miners, who brought back with them new knowledge and practices—such as the use of mercury in gold-washing. Other innovations came with the introduction of more affordable new technologies. For example, metal detectors were brought from the Gulf countries at the beginning of the gold rush, often by Sudanese working there. Most gold mining in Blue Nile remains artisanal. Mechanical tools, such as jackhammers, have been gradually introduced. While some miners still work with hammers, large, stationary or small, mobile ore crushers (known as mills) are also used to turn rocks and stones from the mines into dust, which can then be ‘washed’ to separate the heavier gold from the other material. Washing was previously done with pans of water—moving the pan around until the gold was separated. Now the dust is mostly treated with mercury in basins dug in the ground and covered with plastic sheets (see picture 1). Mercury is added to the dust and the gold dissolves into it. This mixture is then heated until the mercury vaporizes and the gold stays behind. The larger companies that operate in the area mostly work with tailings—the material left over after the initial processing of an ore. They take the dust that remains after artisanal gold washing has taken place and treat this with cyanide, which enables them to extract more gold. Fully industrial-scale mines are rare. Women washing gold in Belguwa market. Regulating the local gold economy In Sudan, the local gold markets are generally situated some distance from mines, and ideally far from residential areas. The markets are locations where miners, mill owners and workers, officials, company agents, investors, traders, grocery shop owners, tea sellers and other service providers meet. This Sudanese method of organizing of the gold sector seems to have influenced gold mining in other African countries. For example, in Morocco, some gold markets are organized in what is known as ‘the Sudanese model’. While some of Blue Nile’s gold markets have emerged informally, the largest in the government controlled areas of the state are organized by state agents who strive to regulate and profit from the sector through taxation. Gold markets have consequently become an important site where the relationship between citizens and state institutions is negotiated. This includes how taxation and public service provision relate to each other, and who controls different parts of the supply chain. Consequently, markets are usually avoided by those who wish to escape taxation and control. For this reason, much of the gold that is extracted in Blue 2 rift valley institute briefing paper march 2020

Nile is not distributed through official channels, but finds its way to international markets through a variety of different routes through the Horn of Africa and across the Red Sea towards the Gulf countries. Blue Nile state has a mix of informal and regulated markets—Belguwa, Maganza, Bulang and Bakori—not including those situated in SPLM-N-held areas. The largest of these is Belguwa in Wad El-Mahi Locality, which is used regularly by about 10,000 miners. While gold mining was historically a communal affair here, in 2016 the Sudanese Mineral Resources Company (SMRC)—the main governmental regulator of the sector—started to take control and introduced taxes and other levies on ore brought to the gold market. The expectation among the miners was that SMRC would provide reciprocal services, such as health services or technical support, in exchange for the taxes they collected. But these expected services were slow to arrive. The SMRC presence came in the form of a combination of geologists and national security agents. It was unclear to local citizens whether it was a provider of state services, a regulator charged with improving dangerous labour practices, or an extension of the armed forces that dominate gold mining in other parts of the war-ravaged state. Suspicions and underlying tensions came to the fore in late 2018 when the Blue Nile state government doubled the tax from 10 to 20 percent on gold after washing. The miners refused the tax and in February 2019 protesters burnt the offices of the SMRC and national security in Belguwa. The legislative council of the state reacted and fixed the tax at 120 SDG per sack of ore brought to the market, rather than taking a percentage of profits as before. However, more tensions occurred with residents of the settlements around Belguwa. Investors linked to the Bashir regime had started—often in joint ventures with foreign investors—to establish factories where gold was extracted using cyanide, which caused major environmental damage in the area. Their close connection with governmental and private security forces—employed to secure the mining areas—gave them little regard for the harm their operation was doing to local communities. But when the rule of Omar Al-Bashir came to an end in April 2019 after months of popular protests, local communities saw an opportunity to assert their demands on state-linked companies’ mining practices. At the end of April 2019, people living around Belguwa set fire to one of the gold processing factories. The state’s responses was initially harsh. Factory workers who had been cooperating with the protesters were fired, and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) moved in, arresting protesters and closing the local market. The military took control of the area, and the factories continued to operate under the auspices of SAF’s industrial business, the Military Industrial Corporation (MIC). But when the market was reopened a few months later, SMRC started to introduce some services, such as an ambulance, and applied more pressure on companies in the area to respect corporate social responsibility. This appears to have contributed to a reduction in direct tensions between citizens and military personnel in the market and may lead to a new and improved era of state-citizen relations. Women and children in the labour market The gold market in Belguwa is situated in an area where women play an important role in the mining process, both collecting ore and washing the gold. Historically in Sudan this role was not unusual. Along the Blue Nile valley and its tributaries gold washing was an activity that women would do in addition to agriculture and small livestock herding. But, in most other parts of Sudan—particularly Darfur, North Kordofan, Northern State, River Nile State and Red Sea State—the recent gold rush has been exclusive to men. Female miners have become a rarer phenomenon, mostly limited to Blue Nile and South Kordofan. In these areas, women are most visibly involved in the collection of stones and washing of gold-bearing dust, although some also own mine shafts where they will occasionally employ men as workers. Others will collect stones and dust around abandoned mining shafts (see Picture 2), partly crushing and washing the ore locally, partly bringing what they collected to the market to process it there. how sudan’s gold boom is changing labour relations in blue nile state 3

Women working in gold mines, close to Belguwa market. Women’s work is often considered by their male counterparts as ‘light work’ or opportunistic benefit from ‘real mining’—an effort that garners small amounts of gold dust and low profits. The stones and dust they gather is called rutuut (also the name for gold obtained from this effort). At gold markets around Belguwa this has meant that local officials often act leniently with women miners and do not make them pay taxes to enter the markets. Some women have benefitted from this by helping male miners to avoid paying taxes on the ore that they have collected by transporting it into the market, claiming that they have mined it themselves. This arrangement shows that a reciprocal relationship between the miners and the authorities–-in which miners pay taxes and receive services in return—is far from consolidated. It is also an example of short-term economic empowerment, but those who benefit are unlikely to transition into a new socio-economic status. A closer look at the health consequences of gold extraction also shows that any economic benefit is likely to be offset by the negative physical consequences of involvement in the sector. This also applies to the children who find some economic opportunities in the gold market. Many can be observed around the stone crushers collecting dust, which they then wash with water or mercury (see Picture 3). At first glance this appears to be an extension of the duties that the region’s children assume in their early years, which also includes helping in the fields and taking care of livestock. But many of the children in the gold market are from families that have been broken by displacement and abandonment. Gold is a short-term remedy that partially tackles economic hardship, but daily exposure to toxic chemicals and dust, without any form of protective equipment, causes physical damage that will have a more lasting effect. 4 rift valley institute briefing paper march 2020

A boy collecting dust next to a stone mill, Belguwa market. Several boys interviewed in the market fled war in different areas of Sudan. Some of them self-financed their schooling in Belguwa, paying the fees and other expenses with money from rutuut gold collected from dust around the mines. Conclusion Over a decade since the start of Sudan’s gold boom, assessing how it has affected people living and working in mining areas is a challenge. Gold markets, such as those in Belguwa, show how labour relations are constantly shifting as new arrangements emerge with new opportunities. But these shifts can be doubleedged: while gold mining may open new economic options for some, it also risks the health of many involved, particularly those working at the rougher end of a still weakly regulated industry. At the same time, state-citizen relations are being negotiated through seemingly trivial details such as the tax to be paid for a sack of ore. The fact that these taxes and levies are not always accepted, and are sometimes openly challenged, shows that the legitimacy and control of state agents in these areas is far from settled. In these times of national political change, the government’s capacity to establish generally acceptable and economically just policies of natural resource extraction is still low. How far this can be achieved—in Blue Nile and more widely—will be a key dynamic as Sudan’s political transition plays out across the country. Credits This briefing was written by Mohamed Salah and Enrico Ille. This briefing is a product of the X-Border Local Research Network, a component of DFID’s Cross- Border Conflict—Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) programme, funded by UKaid from the UK government. The programme carries out research work to better understand the causes and impacts of conflict in border areas and their international dimensions. It supports more effective policymaking and development programming and builds the skills of local partners. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. The Rift Valley Institute works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright Rift Valley Institute 2020. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). how sudan’s gold boom is changing labour relations in blue nile state 5

Sudan's Blue Nile state, which borders Ethiopia's Benishangul-Gumuz region on its eastern side, and South Sudan's Upper Nile region on its south-west frontier, has a long history of small-scale artisanal gold mining. Gold is found in the region's hills and in the alluvial planes south of the Blue Nile. In Blue Nile, artisanal gold .

Liftcrane Boom Capacities 888 SERIES 2 Boom No. 22EL 179,100 Lb. Crane Counterweight 44,000 Lb. Carbody Counterweight 360 Degree Rating Meets ANSI B30.5 Requirements Oper. Rad. Feet Boom Ang. Deg. Boom Point Elev. Feet Boom Capacity Crawlers Retracted Pounds Boom Capacity Crawlers Extended Pounds 100 Ft. Boom *b *b *b * * * * Oper. Rad. Feet .

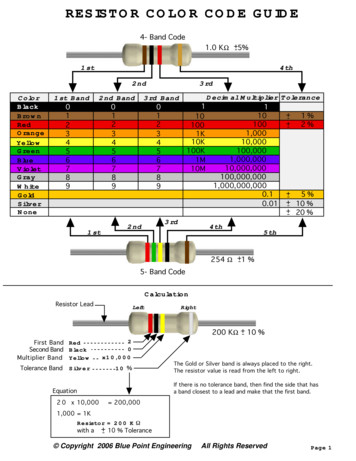

.56 ohm R56 Green Blue Silver.68 ohm R68 Blue Gray Silver.82 ohm R82 Gray Red Silver 1.0 ohm 1R0 Brown Black Gold 1.1 ohm 1R1 Brown Brown Gold 1.5 ohm 1R5 Brown Green Gold 1.8 ohm 1R8 Gray Gold 2.2 ohm 2R2 Red Red Gold 2.7 ohm 2R7 Red Purple Gold 3.3 ohm 3R3 Orange Orange Gold 3.9 ohm 3R9 Orange White Gold 4.7 ohm 4R7 Yellow Purple Gold 5.6 ohm 5R6 Green Blue Gold 6.8 ohm 6R8 Blue Gray Gold 8 .

Gold 6230 2.1 20 27.5 10.4 Y 125 Gold 6226 2.7 12 19.25 10.4 Y 125 Gold 6152 2.1 22 30 10.4 Y 140 Gold 6140 2.3 18 25 10.4 Y 140 Gold 6130 2.1 16 22 10.4 Y 125 Gold 5220 2.2 18 24.75 10.4 Y 125 Gold 5218R 2.1 20 27.5 10.4 Y 125 Gold 5218 2.3 16 22 10.4 Y 105 Gold 5217 3 8 11 10.4 Y 115 Gold 5215 2.5 10 13.75 10.4 Y 85 Gold 5120 2.2 14 19 10.4 Y .

Level Crossing controlled by Flashing Lights and Half -Boom Gates. Level Crossing controlled by Flashing Lights and Four Quadrant Half -Boom Gates. In this Standard the term Half-Boom Gate shall be synonymous with the terms Boom Barrier or Boom Gate. Four quadrant gates shall refer to application of half boom barriers arranged to

Link‐Belt Cranes 218 HSL Main Boom Working Range Diagram 40' TO 230' TUBE BOOM Notes: 1. Boom geometry shown is for unloaded condition and crane standing level on firm supporting surface. Boom deflection, subsequent radius, and boom angle change must be accounted for when applying load to hook. 2.

v1.0 March 8, 2017 3 Boom Hoist Rope drum and its drive, or other mechanism, for controlling the angle of a lattice boom crane. Boom Length The distance along a straight line through the centreline of the boom foot pin to the centreline of the boom head sheave shaft, measured along the longitudinal axis of the boom.

SPECIFICATIONS Type Crawler mounted, Lattice boom, Hydraulic controlled Maximum lift capacity 320,000 lbs (145,200 kg) @ 15’ operating radius (50’ boom) Basic boom length 50’ (15.2 m) Maximum boom length 250’ (76.2 m) Basic boom & jib length 90’ 40’ (27.4 m 12.2 m) Maximum boom & jib length 200’ 100’ (61.0 m 30.5 m) .

By engaging with and completing the BSc degree in Chemistry the graduate is exposed to an internationally-renowned research school and undertakes an individual research project within a dynamic research group. In so doing, they develop: The application of knowledge and understanding gained throughout the curriculum to the solution of qualitative and quantitative problems of a familiar and .