Online Communication And Adolescent Relationships

Online Communication and Adolescent RelationshipsOnline Communication and AdolescentRelationshipsKaveri Subrahmanyam and Patricia GreenfieldSummaryOver the past decade, technology has become increasingly important in the lives of adolescents.As a group, adolescents are heavy users of newer electronic communication forms such asinstant messaging, e-mail, and text messaging, as well as communication-oriented Internet sitessuch as blogs, social networking, and sites for sharing photos and videos. Kaveri Subrahmanyamand Patricia Greenfield examine adolescents’ relationships with friends, romantic partners,strangers, and their families in the context of their online communication activities.The authors show that adolescents are using these communication tools primarily to reinforceexisting relationships, both with friends and romantic partners. More and more they are integrating these tools into their “offline” worlds, using, for example, social networking sites to getmore information about new entrants into their offline world.Subrahmanyam and Greenfield note that adolescents’ online interactions with strangers, whilenot as common now as during the early years of the Internet, may have benefits, such asrelieving social anxiety, as well as costs, such as sexual predation. Likewise, the authors demonstrate that online content itself can be both positive and negative. Although teens find valuablesupport and information on websites, they can also encounter racism and hate messages.Electronic communication may also be reinforcing peer communication at the expense ofcommunication with parents, who may not be knowledgeable enough about their children’sonline activities on sites such as the enormously popular MySpace.Although the Internet was once hailed as the savior of education, the authors say that schoolstoday are trying to control the harmful and distracting uses of electronic media while childrenare at school. The challenge for schools is to eliminate the negative uses of the Internet and cellphones in educational settings while preserving their significant contributions to education andsocial connection.www.futureofchildren.orgKaveri Subrahmanyam is a professor of psychology at California State University–Los Angeles, and associate director of the Children’sDigital Media Center, UCLA/CSULA. Patricia Greenfield is a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California–LosAngeles and director of the Children’s Digital Media Center, UCLA/CSULA.VOL. 18 / NO. 1 / S PR ING 2008119

TKaveri Subrahmanyam and Patricia Greenfieldhe communication functions ofelectronic media are especiallypopular among adolescents.Teens are heavy users of newcommunication forms such asinstant messaging, e-mail, and text messaging,as well as communication-oriented Internetsites such as blogs, social networking, photoand video sharing sites such as YouTube,interactive video games, and virtual realityenvironments, such as Second Life. Questionsabound as to how such online communicationaffects adolescents’ social development, inparticular their relationship to their peers,romantic partners, and strangers, as well astheir identity development, a core adolescentdevelopmental task.In this article, we first describe how adolescents are using these new forms of electronicmedia to communicate and then present atheoretical framework for analyzing theseuses. We discuss electronic media and relationships, analyzing, in turn, relationshipswith friends, romantic partners, strangers,and parents. We then explore how parentsand schools are responding to adolescents’interactions with electronic media. Finally,we examine how adolescents are usingelectronic media in the service of identityconstruction.Adolescents have a vast array of electronictools for communication—among them,instant messaging, cell phones, and socialnetworking sites. These tools are changingrapidly and are just as rapidly becoming independent of a particular hardware platform.Research shows that adolescents use thesecommunication tools primarily to reinforceexisting relationships, both friendships andromantic relationships, and to check out thepotential of new entrants into their offlineworld.1 But while the Internet allows teens to12 0T HE F UT UR E OF C HI LDRE Nnourish existing friendships, it also expandstheir social networks to include strangers.The newly expanded networks can be usedfor good (such as relieving social anxiety) orfor ill (such as sexual predation). Althoughresearchers have conducted no rigorousexperiments into how adolescents’ wide useof electronic communication may be affectingtheir relationships with their parents, indications are that it may be reinforcing peer communication at the expense of communicationwith parents. Meanwhile, parents are increasingly hard-pressed to stay aware of exactlywhat their children are doing, with newerforms of electronic communication suchas social networking sites making it harderfor them to control or even influence theirchildren’s online activities. Schools too arenow, amidst controversy and with difficulty,trying to control the distracting uses of theInternet and other media such as cell phoneswhile children are at school. The challengefor parents and schools alike is to eliminatethe negative uses of electronic media whilepreserving their significant contributions toeducation and social connection.Electronic Media in the Service ofAdolescent CommunicationTo better understand how adolescents useelectronic media for communication, westart by describing the many diverse ways inwhich such communication can take place.Among youth today, the popular communication forms include e-mail, instant messaging,text messaging, chat rooms, bulletin boards,blogs, social networking utilities such asMySpace and Facebook, video sharing suchas YouTube, photo sharing such as Flickr,massively multiplayer online computer gamessuch as World of Warcraft, and virtual worldssuch as Second Life and Teen Second Life.Table 1 lists these communication forms, the

Online Communication and Adolescent RelationshipsTable 1. Online Communication Form, Electronic Hardware That Supports It, and Function of theCommunication FormCommunication FormElectronic Hardware That Supports ItFunctions EnabledE-mailComputers, cell phones,Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs)Write, store, send, and receive asynchronous messages electronically; can include attachments of word documents, pictures, audio,and other multimedia filesInstant messagingComputers, cell phones, PDAsAllows the synchronous exchange of private messages with anotheruser; messages primarily are in text but can include attachments ofword documents, pictures, audio, and other multimedia filesText messagingCell phones, PDAsShort text messages sent using cell phones and wireless hand-helddevices such as the Sidekick and Personal Digital AssistantsChat roomsComputersSynchronous conversations with more than one user that primarilyinvolve text; can be either public or privateBulletin boardsComputersOnline public spaces, typically centered on a topic (such as health,illnesses, religion), where people can post and read messages;many require registration, but only screen names are visible (suchas www.collegeconfidential.com)BlogsComputersWebsites where entries are typically displayed in reverse chronological order (such as www.livejournal.com); entries can be either publicor private only for users authorized by the blog owner/authorSocial networkingutilitiesComputersOnline utilities that allow users to create profiles (public or private)and form a network of friends; allow users to interact with theirfriends via public and private means (such as messages, instantmessaging); also allow the posting of user-generated content suchas photos and videos (such as www.myspace.com)Video sharingComputers, cell phones,cameras with wirelessAllows users to upload, view, and share video clips (such as www.YouTube.com)Photo sharingComputers, cell phones,cameras with wirelessAllows users to upload, view, and share photos (such as www.Flickr.com); users can allow either public or private accessMassively multiplayerComputersonline computer games(MMOG)Online games that can be played by large numbers of players simultaneously; the most popular type are the massively multiplayer roleplaying games (MMORPG) such as World of WarcraftVirtual worldsOnline simulated 3-D environments inhabited by players who interactwith each other via avatars (such as Teen Second Life)Computerselectronic hardware that supports them, andthe functions that they make possible.Although table 1 lists the various forms ofelectronic hardware that support the different communication forms, these distinctionsare getting blurred as the technologyadvances. For instance, e-mail, which wasoriginally supported only by the computer,can now be accessed through cell phones andother portable devices, such as personaldigital assistants (PDAs), Apple’s iPhone, theSidekick, and Helio’s Ocean. The same is truefor functions such as instant messaging andsocial networking sites such as MySpace.Other communication forms such as YouTubeand Flickr are similarly accessible on portabledevices such as cell phones with cameras andcameras with wireless. Text messagingcontinues to be mostly the province of cellphones although one can use a wired computer to send a text message to a cell phone.As more phones add instant messagingservice, instant messaging by cell phone isalso growing in popularity.2 Although teensuse many of these types of electronic hardware to access the different online communication forms, most research on teens’ use ofelectronic communication has targetedcomputers; where available, we will includeVOL. 18 / NO. 1 / S PR ING 2008121

Kaveri Subrahmanyam and Patricia Greenfieldfindings based on other technologies, such ascell phones.Adolescents are using these differentcommunication forms for many different purposes and to interact with friends,acquaintances, and strangers alike. Teens useinstant messaging mainly to communicatewith offline friends.3 Likewise they use socialnetworking sites to keep in contact with theirpeers from their offline lives, both to makeplans with friends whom they see often andto keep in touch with friends whom they seerarely.4 They use blogs to share details ofeveryday happenings in their life.5Cell phones and text messaging have alsobecome an important communication toolfor teens. Virgin Mobile USA reports thatmore than nine of ten teens with cell phoneshave text messaging capability; two-thirds usetext messaging daily. Indeed, more than halfof Virgin’s customers aged fifteen to twentysend or receive at least eleven text messagesa day, while nearly a fifth text twenty-onetimes a day or more. From October throughDecember 2006, Verizon Wireless hosted17.7 billion text messages, more than doublethe total from the same period in 2005.Adolescents use cell phones, text messaging,and instant messaging to communicate withexisting friends and family.6 Using these toolsto keep in touch with friends is a departurefrom the early days of the Internet, whencontact with strangers was more frequent.But the trend is not surprising given thatyouth are more likely to find their friends andfamily online or with cell phones today thanthey were even five or ten years ago.7Although teens are increasingly using theseelectronic communication forms to contactfriends and family, the digital landscapecontinues to be populated with anonymous12 2T HE F UT UR E OF C HI LDRE Nonline contexts such as bulletin boards, massively multiplayer online games (MMOG),massively multiplayer online role playinggames (MMORPG), and chat rooms whereusers can look for information, find support,play games, role play, or simply engage inconversations. Investigating how technologyuse affects adolescent online communicationrequires taking into account both the activities and the extent of anonymity afforded byan online context, as well as the probability ofcommunicating with strangers compared withfriends in that context.Privacy measures have givenadolescent users a great dealof control over who viewstheir profiles, who views thecontent that they upload,and with whom they interacton these online forums.Electronic communication forms also differboth in the extent to which their content ispublic or private and in the extent to whichusers can keep content private. Public chatrooms and bulletin boards are perhaps theleast private. Screen names of users arepublicly available, although users choosetheir screen names and also whether theirprofile is public or private. Of course, privateconversations between users are not publiclyavailable, and such private messages are typically restricted to other users who have alsoregistered. This restriction precludes lurkersand others not registered with the site fromprivately contacting a user. Communicationthrough e-mail, instant messaging, and textmessaging is ostensibly the most private.

Online Communication and Adolescent RelationshipsAlthough e-mails and transcripts of instantmessaging conversations can be forwardedto third parties, they still remain among themore private spaces of the Internet.For communication forms such as blogs andsocial networking utilities, users have complete control over the extent to which theirentries or profiles are public or private. Blogentries and MySpace profiles, for instance,can be either freely accessed on the Web byanyone or restricted to friends of the author.Recently, MySpace has restricted the abilityof users over age eighteen to become friendswith younger users. Facebook gives users avariety of privacy options to control theprofile information that others, such asfriends and other people in their network,can see. For example, users can blockparticular people from seeing their profile orcan allow specific people to see only theirlimited profile. Searches on the Facebooknetwork or on search engines reveal only auser’s name, the networks they belong to, andtheir profile picture thumbnail. Facebookused to be somewhat “exclusive,” in thatmembers had to have an “.edu” suffix on theire-mail address; the idea was to limit the siteto college and university students. Thatrequirement, however, has recently changed,making Facebook less “private” and morepublic. Most photo sharing sites allow usersto control who views the pictures that theyupload; pictures can be uploaded for publicor private storage and users can control whoviews pictures marked private. YouTube, avery public communication forum, allowsregistered users to upload videos andunregistered users to view most videos; onlyregistered viewers can post comments andsubscribe to video feeds.Finally, although online games and virtualworlds are public spaces, users must beregistered and often must pay a subscriptionfee to access them; users create avatars oronline identities to interact in these worldsand have the freedom to make them resemble or differ from their physical identities.Some virtual worlds such as Second Life arerestricted to people older than eighteen;Teen Second Life is restricted to usersbetween thirteen and seventeen. Severalcontrols have been put in place to protectyouth in these online contexts. One suchcontrol for Teen Second Life is the verification of users, which requires a credit card orPaypal account. Another control is the threatof losing one’s privileges in the site; forinstance, underage users found in the mainarea are transferred to the teen area andoverage users found in the teen area arebanned from both the teen and main areas.These privacy measures have given adolescent users a great deal of control over whoviews their profiles, who views the contentthat they upload, and with whom theyinteract on these online forums. And youngusers appear to be using these controls. Arecent study of approximately 9,000 profileson MySpace found that users do not disclosepersonal information as widely as many fear:40 percent of profiles were private. In factonly 8.8 percent of users revealed their name,4 percent revealed their instant messagingscreen name, 1 percent included an e-mailaddress, and 0.3 percent revealed theirtelephone number.8 As dana boyd points out,however, an intrinsic limitation of privacy inelectronic communication is that words canbe copied or altered and shared with otherswho were not the intended audience.9Further research is needed to learn how thisfeature affects social relationships.Privacy controls on networking sites alsomean that adolescents can restrict parentalVOL. 18 / NO. 1 / S PR ING 2008123

Kaveri Subrahmanyam and Patricia Greenfieldaccess to their pictures, profiles, and writings.In fact, on Facebook, even if teens give theirparents access to their profiles, they can limitthe areas of their profile that their parentscan view. We recently conducted a focusgroup study that revealed that some teensmay go as far as to have multiple MySpaceprofiles, some of which their parents canaccess, others of which they cannot, and stillothers that they do not know exist. Monitoring and controlling youth access to thesecommunication forms is growing ever morechallenging, and it is important for parents toinform themselves about these online formsso they can have meaningful discussionsabout them with their adolescents.One key question for research is whetherthese new online communication forms havealtered traditional patterns of interactionamong adolescents. Is time spent in onlinecommunication coming at the expense of timespent in face-to-face communication? Or istime spent online simply substituting for timethat would have been spent on the telephonein earlier eras? Research has shown that overthe past century adolescence has becomemore and more separated from adult life; mostadolescents today spend much of their timewith their peers.10 An equally importantquestion is whether adolescents’ onlinecommunication is changing the amount andnature of interactions with families andrelatives. Research has not yet even consistently documented the time spent by adolescents in different online communicationvenues. One difficulty in that effort is that themultitasking nature of most online communication makes it hard for subjects to provide arealistic estimate of the time they spend ondifferent activities. Recall errors and biasescan further distort estimates. Researchers havetried to sidestep this problem by using diarystudies and experience-sampling methods in12 4T HE F UT UR E OF C HI LDRE Nwhich subjects are beeped at various pointsthroughout the day to record and study theiractivities and moods. But current diary studiesof teen media consumption do not address thequestions of interest here. The rapidly shiftingnature of adolescent online behavior alsocomplicates time-use studies. For instance, onthe blogging site Xanga, an average user spentan hour and thirty-nine minutes in October2002, but only eleven minutes in September2006. Similarly, recent media reports suggestthat the once-popular Friendster andMySpace sites have been supplanted byFacebook among adolescents.11 These shifts inpopularity mean that data on time usagequickly get outdated; clearly new paradigmsare needed to study these issues.Theoretical FrameworkOur theoretical framework draws on JohnHill’s claim that adolescent behavior is bestunderstood in terms of the key developmentaltasks of adolescence—identity, autonomy,intimacy, and sexuality—and the factors, suchas pubertal and cognitive changes, and thevariables, such as gender and social class, thatinfluence them.12 Extending his ideas, wepropose that for today’s youth, media technologies are an important social variable andthat physical and virtual worlds are psychologically connected; consequently, the virtualworld serves as a playing ground for developmental issues from the physical world, such asidentity and sexuality.13 Thus understandinghow online communication affects adolescents’ relationships requires us to examinehow technology shapes two important tasks ofadolescence—establishing interpersonalconnections and constructing identity.Electronic Media andRelationshipsEstablishing interpersonal connections—both those with peers, such as friendships

Online Communication and Adolescent Relationshipsand romantic relationships, and those withparents, siblings, and other adults outsidethe family—is one of the most importantdevelopmental tasks of adolescence.14 Aselectronic media technologies have becomeimportant means of communicating withothers, it is important to consider them in thecontext of the interpersonal relationships inadolescents’ lives. Two themes have frameddiscussions of adolescent online communication and relationships. One is concern aboutthe nature and quality of online and offlinerelationships. The other is how online communication affects adolescents’ relationshipsand well-being and whether the effects arepositive or negative. We next address theseissues. Although research on adolescencehas historically not considered relationshipswith strangers, we include that relationshiphere, as the Internet has opened up a worldbeyond one’s physical setting.Electronic Media and Relationshipswith FriendsWe first examine the role of electronic mediain youth’s existing friendships. One study ofdetailed daily reports of home Internet usefound that adolescents used instant messagingand e-mail for much of their online interactions; they communicated mostly with friendsfrom offline lives about everyday issues suchas friends and gossip.15 Another study foundthat teens use instant messaging in particular as a substitute for face-to-face talk withfriends from their physical lives.16 Accordingto this study, conducted in 2001–02, teensfeel less psychologically close to their instantmessaging partners than to their partners inphone and face-to-face interactions. Teensalso find instant messaging less enjoyablethan, but as supportive as, phone or face-toface interactions. They find instant messagingespecially useful to talk freely to members ofthe opposite gender. The authors of the studyspeculate that teens have so wholly embracedinstant messaging despite its perceivedlimitations because it satisfies two importantdevelopmental needs of adolescence—connecting with peers and enhancing theirgroup identity by enabling them to joinoffline cliques or crowds without their moreformal rules.Although social networking sites are alsoused in the context of offline friendships,this is true mostly for girls. The 2006 Pewsurvey study on social networking sites andteens found that girls use such sites to reinforce pre-existing friendships whereas boysuse them to flirt and make new friends.17Text messaging on cell phones has recentlybecome popular among U.S. teens; they arenow following youth in the United Kingdom,Europe, and Asia who have widely adoptedit and enmeshed it in their lives. Adolescentsexchange most of their text messages withtheir peers.18 To study the communicativepurposes of text messaging, one study askedten adolescents (five boys and five girls) tokeep a detailed log of the text messages thatthey sent and received for seven consecutivedays. Analysis of the message logs revealedthree primary conversation threads: chatting (discussing activities and events, gossip,and homework help), planning (coordinatingmeeting arrangements), and coordinatingcommunication (having conversations abouthaving conversations). The teens ended mosttext conversations by switching to anothersetting such as phone, instant messaging, orface-to-face.19Effects of electronic communication onfriendships. How does adolescents’ electroniccommunication with their friends affecttheir friendship networks and, in turn, theirwell-being? According to a 2001 survey bythe Pew Internet and American Life Project,VOL. 18 / NO. 1 / S PR ING 2008125

Kaveri Subrahmanyam and Patricia Greenfield48 percent of online teens believe that theInternet has improved their relationshipswith friends; the more frequently they usethe Internet, the more strongly they voicethis belief. Interestingly, 61 percent feel thattime online does not take away from timespent with friends.20One recent study appears to support adolescents’ self-reported beliefs about how theInternet affects their friendships. A surveystudy of preadolescent and adolescent youthin the Netherlands examined the linkbetween online communication and relationship strength.21 Eighty percent of thosesurveyed reported using the Internet tomaintain existing friendship networks.Participants who communicated more oftenon the Internet felt closer to existing friendsthan those who did not, but only if they wereusing the Internet to communicate withfriends rather than strangers. Participantswho felt that online communication was moreeffective for self-disclosure also reportedfeeling closer to their offline friends thanadolescents who did not view online communication as allowing for more intimate selfdisclosure.Whereas survey participants who used instantmessaging communicated primarily withexisting, offline friends, those who visitedchat rooms communicated with existingfriends less often. This pattern makes sensebecause chat is generally a public venueproviding wide access to strangers and littleaccess to friends, whereas instant messaging is primarily a private medium. But theresearch leaves unanswered the question ofwhether chat decreases communication withexisting friends or whether teens with weakerfriendship networks use chat more. Theauthors completed their survey before socialnetworking sites had become popular in the12 6T HE F UT UR E OF C HI LDRE NNetherlands; only 8 percent of their respondents used the most popular Dutch socialnetworking site. The study did not assess therelationship between the use of social networking sites and existing friendships.Researchers have uncovered some evidencethat the feedback that teens receive in socialnetworking may be related to their feelingsabout themselves. A recent survey of 881Dutch adolescents assessed how using afriend networking site (CU2) affected theirself-esteem and well-being.22 The study’sauthors concluded that feedback from the siteinfluenced self-esteem, with positive feedbackenhancing it and negative tone decreasing it.Although most adolescents (78 percent)reported receiving positive feedback always orpredominantly, a small minority (7 percent)reported receiving negative feedback alwaysor predominantly. The study, however, wasbased entirely on participants’ self-assessments as to the kind of feedback theyreceived; there was no independent assessment of whether it was positive or negative. Itis impossible to tell whether negative feedback per se reduced self-esteem or whetherparticipants with lower self-esteem typicallyperceived the feedback they received as morenegative, which in turn caused a further dip intheir self-esteem. Nor did the analysis takeinto account whether friends or strangersprovided the feedback.Even when adolescents are communicatingwith their friends, social networking sitessuch as MySpace may by their very nature betransforming their peer relations. These sitesmake communication with friends public andvisible. Through potentially infinite electroniclists of friends and “friends of friends,” theybring the meaning of choosing one’s socialrelationships to a new extreme. They havethus become an essential part of adolescent

Online Communication and Adolescent Relationshipspeer social life while leading to a redefinitionof the word “friend.” A recent focus groupstudy of MySpace on a college campus foundthat most participants had between 150and 300 “friends” on their MySpace site.23Friends’ photos and names are displayed onusers’ profiles, and each profile includes a listof “top” friends, ranging from a “top four”to a “top twenty-four.” Such public displayof best friends seems a potentially transformative characteristic of a social networkingsite. But how does making (and not making)someone’s “top” friends list affect adolescentrelationships and self-esteem? This is animportant question for future research in thearea of adolescent peer relations.Initial qualitative evidenceis that the ease of electroniccommunication may bemaking teens less interestedin face-to-face communicationwith their friends.Other technologies clearly form barriersagainst all face-to-face communication. Walking through an unfamiliar university campusrecently, one of us had difficulty getting theattention of students hooked up to iPods toget directions to a particular building. Initialqualitative evidence is that the ease of electronic communication may be making teensless interested in face-to-face communicationwith their friends.24 More research is neededto see how widespread this phenomenon isand what it does to the emotional quality ofa relationship.Electronic media and bullying. The newsmedia are increasingly reporting thatadolescents are using electronic technologiessuch as cell phones, text messages, instantmessages, and e-mail to bully and victimizetheir peers. In a 2005 survey conducted in theUnited Kingdom, 20 percent of the 770respondents, aged eleven to nineteen,reported being bullied or receiving a threatvia e-mail, Internet, chat room, or text, and 11percent reported sending a bullying orthreatening message to someone else. Textbullying was most commonly reported, with14 percent reporting being bullied by mobiletext messaging. Bullying in Internet chatrooms and through e-mails was reported by 5percent and 4 percent of the sample, respectively. A new form of harassment appears tobe emerging through cell phone cameras: 10percent reported feeling embarrassed,uncomfortable, or threatened by a picturethat someone took of them with a cell phonecamera. The majority of the respondentsreported knowing the person who bullied orthreatened them.25Similar trends have been found in the UnitedStates. The second Youth Internet Safety Survey (YISS-2) conducted in 2005 found that9 perc

online contexts such as bulletin boards, mas-sively multiplayer online games (MMOG), massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPG), and chat rooms where users can look for information, find support, play games, role play, or simply engage in conversations. Investigating h

Development plan. The 5th "Adolescent and Development Adolescent - Removing their barriers towards a healthy and fulfilling life". And this year the 6th Adolescent Research Day was organized on 15 October 2021 at the Clown Plaza Hotel, Vientiane, Lao PDR under the theme Protection of Adolescent Health and Development in the Context of COVID-19.

Adolescent & Young Adult Health Care in Texas A Guide to Understanding Consent & Confidentiality Laws Adolescent & Young Adult Health National Resource Center Center for Adolescent Health & the Law March 2019 3 Confidentiality is not absolute. To understand the scope and limits of legal and ethical confidentiality protections,

for Adolescent Substance Use Disorder Zachary W. Adams, Ph.D., HSPP. Riley Adolescent Dual Diagnosis Program. Adolescent Behavioral Health Research Program. Department of Psychiatry. . NIDA Principles of Adolescent Substance Use Disorder Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. www.drugabuse.gov.

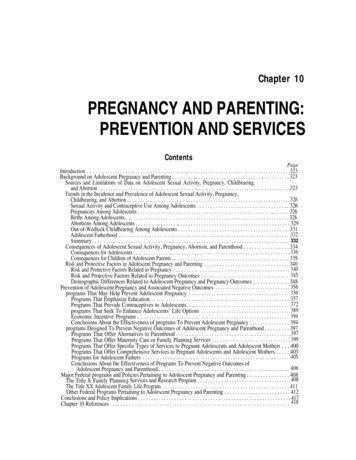

associated with adolescent pregnancy and parenting, and major Federal policies and programs pertaining to adolescent pregnancy and parenting. The chapter ends with conclusions and policy implications. Background on Adolescent Pregnancy and Parenting Sources and Limitations of Data on Adolescent Sexual Activity, Pregnancy, Childbearing, and Abortion

theoretical models. Child and adolescent mental health encompasses a large area and it is difficult to fully explore them all within the confines of a chapter; so some areas have a larger focus here than others. CHILD AND ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEALTH: A STRATEGIC VIEW Child and adolescent mental health is a relatively new psychiatric healthcare .

Fellowship Program. Fellows in the Reproductive Endocrinology Fellowship at Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC also participate in the pediatric and adolescent gynecology sessions. CLINICAL ACTIVITIES T he Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine provides a diverse program of primary care and consultative adolescent medicine.

He is a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, Adult Psychiatrist and Pediatrician, who has for over 20 years passionately pursued the vision, design, development and delivery of innovations in technology, education . This presentation will review adolescent development, highlight research about the impact of social media on adolescent wellbeing .

child relationship into emerging adulthood (Nelson and Padilla-Walker (2013). Parental . involvement. in an adolescent's life, characterised by investment of time and resources into an adolescent's school and leisure activities , is predictive of positive adolescent