Give Me Liberty 3rd Edition

C HAPTER 201919Schenck v. United States1920American Civil Liberties Unionestablished1921Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti1922Washington Naval ArmsConferenceHollywood adopts the HayscodeCable ActHerbert Hoover’s AmericanIndividualism1923Meyer v. Nebraska1924Immigration ActCongress grants all Indiansborn in the United StatesAmerican citizenship1925Scopes trialBruce Barton’s The ManNobody Knows1927Charles Lindbergh fliesnonstop over the Atlantic1927– President Coolidge vetoes1928 McNary-Haugen farm bill1928Claude McKay’s Home toHarlem1929Robert and Helen Lynd’sMiddletownStock market crashesSheppard-Towner Act of 1921repealed1930Hawley-Smoot Tariff1932Bonus march on WashingtonReconstruction FinanceCorporation organized

From Business Cultureto Great Depression:The Twenties, 1920–1932THE BUSINESS OF AMERICATHE CULTURE WARSA Decade of ProsperityA New SocietyThe Limits of ProsperityThe Farmers’ PlightThe Image of BusinessThe Decline of LaborThe Equal Rights AmendmentWomen’s FreedomThe Fundamentalist RevoltThe Scopes TrialThe Second KlanClosing the Golden DoorRace and the LawPluralism and LibertyPromoting ToleranceThe Emergence of HarlemThe Harlem RenaissanceBUSINESS AND GOVERNMENTThe Retreat from ProgressivismThe Republican EraCorruption in GovernmentThe Election of 1924Economic DiplomacyTHE BIRTH OF CIVILLIBERTIESThe “Free Mob”A “Clear and Present Danger”The Court and Civil LibertiesTHE GREAT DEPRESSIONThe Election of 1928The Coming of the DepressionAmericans and the DepressionResignation and ProtestHoover’s ResponseThe Worsening EconomicOutlookFreedom in the Modern WorldBlues, a 1929 painting by Archibald Motley Jr., depicts one side of the 1920s: dance halls,jazz bands, and drinking despite the advent of Prohibition.

F OCUS Q UESTIONS Who benefited and whosuffered in the new consumer society of the 1920s? In what ways did thegovernment promote business interests in the 1920s? Why did the protection ofcivil liberties gain importance in the 1920s? What were the majorflash points between fundamentalism and pluralism in the 1920s? What were the causesof the Great Depression,and how effective werethe government’sresponses by 1932? lIn May 1920, at the height of the postwar Red Scare, police arrested twoItalian immigrants accused of participating in a robbery at a SouthBraintree, Massachusetts, factory in which a security guard was killed.Nicola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, an itinerantunskilled laborer, were anarchists who dreamed of a society in whichgovernment, churches, and private property had been abolished. Theysaw violence as an appropriate weapon of class warfare. But very littleevidence linked them to this particular crime. One man claimed to haveseen Vanzetti at the wheel of the getaway car, but all the other eyewitnessesdescribed the driver quite differently. Disputed tests on one of the sixbullets in the dead man’s body suggested that it might have been fired froma gun owned by Sacco. Neither fingerprints nor possession of stolen moneylinked either to the crime. In the atmosphere of anti-radical and antiimmigrant fervor, however, their conviction was a certainty. “I havesuffered,” Vanzetti wrote from prison, “for things that I am guilty of. I amsuffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have sufferedbecause I was an Italian, and indeed I am an Italian.”Although their 1921 trial had aroused little public interest outside theItalian-American community, the case of Sacco and Vanzetti attractedinternational attention during the lengthy appeals that followed. Therewere mass protests in Europe against their impending execution. In theUnited States, the movement to save their lives attracted the support of animpressive array of intellectuals, including the novelist John Dos Passos,the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Felix Frankfurter, a professor atHarvard Law School and a future justice of the Supreme Court. Inresponse to the mounting clamor, the governor of Massachusettsappointed a three-member commission to review the case, headed byAbbott Lawrence Lowell, the president of Harvard University (and formany years an official of the Immigration Restriction League). Thecommission upheld the verdict and death sentences, and on August 23,1927, Sacco and Vanzetti died in the electric chair. “It is not everyprisoner,” remarked the journalist Heywood Broun, “who has a presidentof Harvard throw the switch for him.”The Sacco-Vanzetti case laid bare some of the fault lines beneath thesurface of American society during the 1920s. The case, the writerEdmund Wilson commented, “revealed the whole anatomy of Americanlife, with all its classes, professions and points of view and . . . it raisedalmost every fundamental question of our political and social system.” Itdemonstrated how long the Red Scare extended into the 1920s and howpowerfully it undermined basic American freedoms. It reflected the fiercecultural battles that raged in many communities during the decade. Tomany native-born Americans, the two men symbolized an alien threat totheir way of life. To Italian-Americans, including respectable middle-classorganizations like the Sons of Italy that raised money for the defense, the

Who benefited and who suffered in the new consumer society of the 1920s?819A 1927 photograph shows Nicola Saccoand Bartolomeo Vanzetti outside thecourthouse in Dedham, Massachusetts,surrounded by security agents andonlookers. They are about to enter thecourthouse, where the judge willpronounce their death sentence.outcome symbolized the nativist prejudices and stereotypes that hauntedimmigrant communities. To Dos Passos, the executions underscored thesuccess of the anti-radical crusade: “They are stronger. They are rich. Theyhire and fire the politicians, the old judges, . . . the college presidents.” DosPassos’s lament was a bitter comment on the triumph of pro-businessconservatism during the 1920s.In popular memory, the decade that followed World War I is recalled asthe Jazz Age or the Roaring Twenties. With its flappers (young, sexuallyliberated women), speakeasies (nightclubs that sold liquor in violation ofProhibition), and a soaring stock market fueled by easy credit and a getrich-quick outlook, it was a time of revolt against moral rules inheritedfrom the nineteenth century. Observers from Europe, where classdivisions were starkly visible in work, politics, and social relations,marveled at the uniformity of American life. Factories poured outstandardized consumer goods, their sale promoted by national advertisingcampaigns. Conservatism dominated a political system from whichradical alternatives seemed to have been purged. Radio and the moviesspread mass culture throughout the nation. Americans seemed to dressalike, think alike, go to the same movies, and admire the same largerthan-life national celebrities.Many Americans, however, did not welcome the new secular, commercial culture. They resented and feared the ethnic and racial diversity ofAmerica’s cities and what they considered the lax moral standards ofurban life. The 1920s was a decade of profound social tensions—betweenrural and urban Americans, traditional and “modern” Christianity, participants in the burgeoning consumer culture and those who did not fullyshare in the new prosperity.

820Ch. 20 From Business Culture to Great DepressionTHE BUSINESS OF AMERICATHE BUSINESS OF AMERICAAAdvertisements, like this one for arefrigerator, promised that consumer goodswould enable Americans to fulfill theirhearts’ desires.The spread of the telephone networkhastened the nation’s integration andopened further job opportunities forwomen. Lewis Hine photographed thistelephone operator in the 1920s.DECADEOFPROSPERITY“The chief business of the American people,” said Calvin Coolidge, whobecame president after Warren G. Harding’s sudden death from a heartattack in 1923, “is business.” Rarely in American history had economicgrowth seemed more dramatic, cooperation between business and government so close, and business values so widely shared. After a sharp postwarrecession that lasted into 1922, the 1920s was a decade of prosperity.Productivity and economic output rose dramatically as new industries—chemicals, aviation, electronics—flourished and older ones like food processing and the manufacture of household appliances adopted HenryFord’s moving assembly line.The automobile was the backbone of economic growth. The most celebrated American factories now turned out cars, not textiles and steel as inthe nineteenth century. Annual automobile production tripled during the1920s, from 1.5 to 4.8 million. General Motors, which learned the secret ofmarketing numerous individual models and stylish designs, surpassedFord with its cheap, standardized Model T (replaced in 1927 by the ModelA). By 1929, half of all American families owned a car (a figure not reachedin England until 1980). The automobile industry stimulated the expansion of steel, rubber, and oil production, road construction, and other sectors of the economy. It promoted tourism and the growth of suburbs(already, some commuters were driving to work) and helped to reduce ruralisolation.During the 1920s, American multinational corporations extended theirsway throughout the world. With Europe still recovering from the GreatWar, American investment overseas far exceeded that of other countries.The dollar replaced the British pound as the most important currency ofinternational trade. American companies produced 85 percent of theworld’s cars and 40 percent of its manufactured goods. General Electric andInternational Telephone and Telegraph bought up companies in othercountries. International Business Machines (IBM) was the world’s leader inoffice supplies. American oil companies built new refineries overseas.American companies took control of raw materials abroad, from rubber inLiberia to oil in Venezuela.One of the more unusual examples of the global spread of American corporations was Fordlandia, an effort by the auto manufacturer Henry Ford tocreate a town in the heart of Brazil’s Amazon rain forest. Ford hoped tosecure a steady supply of rubber for car tires. But as in the United States,where he had compelled immigrant workers to adopt American dress anddiet, he wanted to bring local inhabitants up to what he considered theproper standard of life (this meant, for example, forbidding his workersfrom using alcohol and tobacco and trying to get them to eat brown riceand whole wheat bread instead of traditional Brazilian foods). Eventually,the climate and local insects destroyed the rubber trees that Ford’s engineers, lacking experience in tropical agriculture, had planted much tooclose together, while the workers rebelled against the long hours of laborand regimentation of the community.

Who benefited and who suffered in the new consumer society of the 1920s?ANEWSOCIETYDuring the 1920s, consumer goods of all kinds proliferated, marketed bysalesmen and advertisers who promoted them as ways of satisfyingAmericans’ psychological desires and everyday needs. Frequently purchased on credit through new installment buying plans, they rapidlyaltered daily life. Telephones made communication easier. Vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and refrigerators transformed work in the homeand reduced the demand for domestic servants. Boosted by Prohibition andan aggressive advertising campaign that, according to the company’s salesdirector, made it “impossible for the consumer to escape” the product, CocaCola became a symbol of American life.Americans spent more and more of their income on leisure activitieslike vacations, movies, and sporting events. By 1929, weekly movie attendance had reached 80 million, double the figure of 1922. Hollywood filmsnow dominated the world movie market. Movies had been producedearly in the century in several American cities, but shortly before WorldWar I filmmakers gravitated to Hollywood, a district of Los Angeles,attracted by the open space, year-round sunshine for outdoor filming, andvaried scenery. In 1910, two French companies, Pathé and Gaumont, hadbeen the world’s leading film producers. By 1925, American releases outnumbered French by eight to one. In the 1920s, both companies abandoned film production for the more profitable business of distributingAmerican films in Europe.Radios and phonographs brought mass entertainment into Americans’living rooms. The number of radios in Americans’ homes rose from 190,000in 1923 to just under 5 million in 1929. These developments helped to create and spread a new celebrity culture, in which recording, film, and sportsstars moved to the top of the list of American heroes. During the 1920s,more than 100 million records were sold each year. RCA Victor sold somany recordings of the great opera tenorEnrico Caruso that he is sometimescalled the first modern celebrity. Hewas soon joined by the film actorCharlie Chaplin, baseball player BabeRuth, and boxer Jack Dempsey. OrdinaryAmericans followed every detail oftheir lives. Perhaps the decade’s greatestcelebrity, in terms of intensive presscoverage, was the aviator Charles Lindbergh, who in 1927 made the first solononstop flight across the Atlantic.André Siegfried, a Frenchman whohad visited the United States four timessince the beginning of the century, commented in 1928 that a “new society” hadcome into being, in which Americansconsidered their “standard of living” a“sacred acquisition, which they willdefend at any price.” In this new “massDuring the 1920s, radio penetratedvirtually the entire country. In thisphotograph, a farmer tunes in to aprogram while milking his cow.821

Ch. 20 From Business Culture to Great Depression822THE BUSINESS OF AMERICAElectric washing machines and Hoovervacuum cleaners (demonstrated by asalesman) were two of the homeappliances that found their way into manyAmerican homes during the 1920s. Thewoman on the right is a cardboard cutout.civilization,” widespread acceptance of going into debt to purchase consumer goods had replaced the values of thrift and self-denial, central tonineteenth-century notions of upstanding character. Work, once seen as asource of pride in craft skill or collective empowerment via trade unions,now came to be valued as a path to individual fulfillment through consumption and entertainment.THEFigure 20.1 HOUSEHOLD1009080ity70tric6050elecPercentage of households having an applianceAPPLIANCES, 1900–193040telephoneerleanm c achineuuvaching FPROSPERITY“Big business in America,” remarked the journalist Lincoln Steffens, “is producing what the socialists held up as their goal—food, shelter, and clothingfor all.” But signs of future trouble could be seen beneath the prosperity ofthe 1920s. The fruits of increased production were very unequally distributed. Real wages for industrial workers (wages adjusted to take account ofinflation) rose by one-quarter between 1922 and 1929, but corporate profitsrose at more than twice that rate. The process of economic concentrationcontinued unabated. A handful of firms dominated numerous sectors ofthe economy. In 1929, 1 percent of the nation’s banks controlled half of itsfinancial resources. Most of the small auto companies that had existed earlier in the century had fallen by the wayside. General Motors, Ford, andChrysler now controlled four-fifths of the industry.At the beginning of 1929, the share of national income of the wealthiest5 percent of American families exceeded that of the bottom 60 percent.A majority of families had no savings, and an estimated 40 percent of thepopulation remained in poverty, unable to participate in the flourishingconsumer economy. Improved productivity meant that goods could beproduced with fewer workers. During the 1920s, more Americans workedin the professions, retailing, finance, and education, but the number ofmanufacturing workers declined by 5 percent, the first such drop in thenation’s history. Parts of New England were already experiencing the

Who benefited and who suffered in the new consumer society of the 1920s?823chronic unemployment caused by deindustrialization. Many of theregion’s textile companies failed in the face of low-wage competition fromsouthern factories, or shifted production to take advantage of the South’scheap labor. Most advertisers directed their messages at businessmen andthe middle class. At the end of the decade, 75 percent of American households still did not own a washing machine, and 60 percent had no radio.THEFA R M E R S’PLIGHTNor did farmers share in the decade’s prosperity. The “golden age” ofAmerican farming had reached its peak during World War I, when the needto feed war-torn Europe and government efforts to maintain high farmprices had raised farmers’ incomes and promoted the purchase of moreland on credit. Thanks to mechanization and the increased use of fertilizerand insecticides, agricultural production continued to rise even when government subsidies ended and world demand stagnated. As a result, farmincomes declined steadily and banks foreclosed tens of thousands of farmswhose owners were unable to meet mortgage payments.For the first time in the nation’s history, the number of farms and farmersdeclined during the 1920s. For example, half the farmers in Montana losttheir land to foreclosure between 1921 and 1925. Extractive industries, likemining and lumber, also suffered as their products faced a glut on the worldmarket. During the decade, some 3 million persons migrated out of ruralareas. Many headed for southern California, whose rapidly growing economy needed new labor. The population of Los Angeles, the West’s leadingindustrial center, a producer of oil, automobiles, aircraft, and, of course,Hollywood movies, rose from 575,000 to 2.2 million during the decade,largely because of an influx of displaced farmers from the Midwest. Wellbefore the 1930s, rural America was in an economic depression.Farmers, like this family of potato growersin rural Minnesota, did not share in theprosperity of the 1920s.

824Ch. 20 From Business Culture to Great DepressionTHEIMAGEOFTHE BUSINESS OF AMERICABUSINESSEven as unemployment remained high in Britain throughout the 1920s, andinflation and war reparations payments crippled the German economy,Hollywood films spread images of “the American way of life” across theglobe. America, wrote the historian Charles Beard, was “boring its way” intothe world’s consciousness. In high wages, efficient factories, and the massproduction of consumer goods, Americans seemed to have discovered thesecret of permanent prosperity. Businessmen like Henry Ford and engineerslike Herbert Hoover were cultural heroes. Photographers like Lewis Hine andMargaret Bourke-White and painters like Charles Sheeler celebrated thebeauty of machines and factories. The Man Nobody Knows, a 1925 best-sellerby advertising executive Bruce Barton, portrayed Jesus Christ as “the greatestadvertiser of his day, . . . a virile go-getting he-man of business,” who “pickedtwelve men from the bottom ranks and forged a great organization.”After the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, discussed in Chapter 18, John D.Rockefeller himself had hired a public relations firm to repair his tarnishedimage. Now, persuaded by the success of World War I’s Committee onPublic Information that it was possible, as an advertising magazine put it,to “sway the minds of whole populations,” numerous firms establishedpublic relations departments. They aimed to justify corporate practices tothe public and counteract its long-standing distrust of big business.They succeeded in changing popular attitudes toward Wall Street.Congressional hearings of 1912–1914 headed by Louisiana congressmanArsène Pujo had laid bare the manipulation of stock prices by a Wall Street“money trust.” The Pujo investigation had reinforced the widespread viewRiver Rouge Plant, by the artist CharlesSheeler, exemplifies the “machine-ageaesthetic” of the

1919 Schenck v. United States 1920 American Civil Liberties Union established 1921 Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti 1922 Washington Naval Arms Conference Hollywood adopts the Hays code Cable Act Herbert Hoover’s American Individualism 1923 Meyer v. Nebraska 1924 Immigration Act Congress grants all Indians

century American poet Samuel Francis Smith wrote the now familiar words: My country, ‘tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty, Of thee I sing POEMS ON LIBERTY: Reflections for Belarus. (Liberty Library. XXI Century). — Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, 2004.— 312 pp. Translation Vera Rich Editor Alaksandra Makavik Art Director Hienad ź .

WAS Liberty images on Docker Hub for Development use Latest WAS V8.5.5. Liberty driver WAS Liberty V9 Beta with Java EE 7 Dockerfiles on WASdev GitHub to: Upgrade the Docker Hub image with Liberty Base or ND commercial license Build your own Docker image for Liberty (Core, Base or ND)

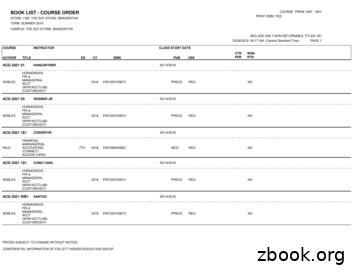

give me liberty!: an american history (fifth brief edition) (vol. 1) 5th 9780393616217 nort req no foner give me liberty: brief (v1)(w/access) (v1) 5th 2017 9780393614152 w. w. req no amh 1020 01 kennedy 05/14/2018 foner give me liberty! brief (w/access code) (v2) 5th 2017 9780393614169 nort req no amh 1020 03 kennedy 05/14/2018 foner give me .

RP 2K, Second Edition RP 2L, Third Edition RP 2M, First Edition Bul 2N, First Edition RP 2P, Second Edition RP 2Q, Second Edition RP 2R, First Edition RP 2T, First Edition Bul 2U, First Edition Bul 2V, First Edition Spec 2W, First Edition RP 2X, First Edition, with Supp 1 Spec 2Y, First Edition

nomic liberty and liberty in general came into being. But again, the theme of liberty was a multifaceted one in the writings of the period. While many authors saw a mutually supportive relation-ship between the growth of commerce and the spread of liberty (de la Court, Trenchard and Gordon in their Cato’s Letters,and Hazeland

Aug 19, 2016 · Liberty may be placed on Tier 1 Liberty and issued a Tier 1 Liberty card. Officers and E-6s and above may be placed on Tier 1 Liberty and issued a Tier 1 Liberty card after completion of the check-in process and command validation that all training requirements are complete. Tier 1 L

all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word "freedom" (amagi), or "liberty." It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project,

all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word "freedom" (amagi), or "liberty." It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project,