U.S.-South Korea Relations

U.S.-South Korea RelationsMark E. ManyinSpecialist in Asian AffairsEmma Chanlett-AverySpecialist in Asian AffairsIan E. RinehartAnalyst in Asian AffairsMary Beth NikitinSpecialist in NonproliferationWilliam H. CooperSpecialist in International Trade and FinanceFebruary 12, 2014Congressional Research Service7-5700www.crs.govR41481

Form ApprovedOMB No. 0704-0188Report Documentation PagePublic reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering andmaintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information,including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, ArlingtonVA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if itdoes not display a currently valid OMB control number.1. REPORT DATE3. DATES COVERED2. REPORT TYPE12 FEB 201400-00-2014 to 00-00-20144. TITLE AND SUBTITLE5a. CONTRACT NUMBERU.S.-South Korea Relations5b. GRANT NUMBER5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER6. AUTHOR(S)5d. PROJECT NUMBER5e. TASK NUMBER5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)Congressional Research Service,The Library of Congress,101Independence Ave, SE,Washington,DC,205409. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATIONREPORT NUMBER10. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S ACRONYM(S)11. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S REPORTNUMBER(S)12. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENTApproved for public release; distribution unlimited13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES14. ABSTRACT15. SUBJECT TERMS16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF:a. REPORTb. ABSTRACTc. THIS PAGEunclassifiedunclassifiedunclassified17. LIMITATION OFABSTRACT18. NUMBEROF PAGESSame asReport (SAR)3719a. NAME OFRESPONSIBLE PERSONStandard Form 298 (Rev. 8-98)Prescribed by ANSI Std Z39-18

U.S.-South Korea RelationsSummaryOverviewSouth Korea is one of the United States’ most important strategic and economic partners in Asia,and for the past five years relations between the two countries (known officially as the Republicof Korea, or ROK) have been arguably at their best state in decades. Members of Congress tendto be interested South Korea-related issues for a number of reasons. First, the United States andSouth Korea have been allies since the early 1950s. The United States is committed to helpingSouth Korea defend itself, particularly against any aggression from North Korea. The UnitedStates maintains about 28,500 troops in the ROK and South Korea is included under the U.S.“nuclear umbrella.” Second, Washington and Seoul cooperate over how to deal with thechallenges posed by North Korea. Third, South Korea’s emergence as a global player on anumber of issues has provided greater opportunities for the two countries’ governments,businesses, and private organizations to interact and cooperate with one another.Fourth, the two countries’ economies are closely entwined and are joined by the Korea-U.S. FreeTrade Agreement (KORUS FTA). South Korea is the United States’ sixth-largest trading partner.The United States is South Korea’s second-largest trading partner. In late 2013 and early 2014,South Korea took the first steps toward possible entry into the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership(TPP) free trade agreement negotiations.Strategic Cooperation and the U.S.-ROK AllianceDealing with North Korea is the dominant strategic element of the U.S.-South Koreanrelationship. Under South Korean President Park Geun-hye, who was inaugurated in February2013, Seoul and Washington have maintained tight coordination over North Korea policy, forgingin effect a joint approach that contains elements of pressure and engagement. For much of 2013,the two countries emphasized the former in the face of a series of provocative actions by NorthKorea. The Obama Administration has supported Park’s “trustpolitik” approach, under whichSeoul has proposed some modest confidence-building measures with and humanitarian assistanceto Pyongyang in order to build trust between the two sides. Thus far, Park has linked large-scaleaid to progress in the denuclearization of North Korea, the United States’ top priority. An issue forthe Obama Administration and Congress is to what extent they will support—or, not oppose—Park’s possible inter-Korean initiatives if they expand further.Since 2009, the United States and South Korea have accelerated steps to reform the U.S.-ROKalliance. Washington and Seoul have initiated plans to relocate U.S. troops on the Peninsula andboost ROK defense capabilities. Some Members of Congress have criticized the relocation, andPark and her predecessor have slowed significantly the planned defense budget increases.Provocations from North Korea have propelled more integrated bilateral planning for respondingto possible contingencies, for instance by adopting policies to respond more swiftly and forcefullyto attacks and by discussing improvements to the two countries’ respective missile defensesystems. In January 2014, the United States and South Korea came to a new five-year SpecialMeasures Agreement (SMA), under which Seoul will raise its host nation support payments forU.S. forces in Korea by 6%, to around 870 million per year.Congressional Research Service

U.S.-South Korea RelationsOn broad strategic matters in East Asia, while South Korean and U.S. perspectives overlap, thereare areas of significant differences. For instance, South Korea often hesitates to take steps thatantagonize China and has shown mistrust of Japan’s efforts to expand its military capabilities.Nuclear Cooperation AgreementIn 2013 the Obama and Park governments agreed to—and in January 2014 Congress voted tosupport—a two-year extension of a bilateral civilian nuclear agreement, which now will expire in2016. The two-year extension is considered a temporary solution to avoid any disruption tonuclear energy trade and provide more time for negotiations to continue. South Korea reportedlyhas requested that the new agreement include provisions that would allow for future uraniumenrichment and reprocessing in South Korea. The Obama Administration has resisted this change,which would pose challenges for U.S. non-proliferation policy.Congressional Research Service

U.S.-South Korea RelationsContentsDevelopments in Late 2013/Early 2014 . 1Cooperation over North Korea Policy . 1Nuclear Energy Cooperation Agreement . 3South Korea Expresses Interest in TPP . 3State of the Alliance. 5Background on U.S.-South Korea Relations . 5Overview . 5Historical Background. 8North Korea in U.S.-ROK relations . 8North Korea Policy Coordination . 8Inter-Korean Relations and Park Geun-Hye’s “Trustpolitik” . 9Deterrence Issues. 11Security Relations and the U.S.-ROK Alliance . 12Upgrades to the Alliance . 12U.S. Alliance and ROK Defense Reform Plans . 13South Korea’s Regional Relations . 19South Korea-Japan Relations . 19South Korea-China Relations . 21South Korea-Iran Relations . 22Economic Relations . 22South Korea’s Economic Performance. 24Nuclear Energy and Non-Proliferation Cooperation . 25Bilateral Nuclear Energy Cooperation . 25South Korean Nonproliferation Policy . 27South Korean Politics . 28A Powerful Executive Branch . 29Political Parties. 29Selected CRS Reports on the Koreas . 31South Korea . 31North Korea . 31FiguresFigure 1. Map of the Korean Peninsula . 7Figure 2. USFK Bases After Realignment Plan Is Implemented . 15Figure 3. Party Strength in South Korea’s National Assembly . 30TablesTable 1. Annual U.S.-South Korea Merchandise Trade, Selected Years. 23Congressional Research Service

U.S.-South Korea RelationsContactsAuthor Contact Information. 32Congressional Research Service

U.S.-South Korea RelationsThis report contains two main parts: a section describing recent events and a longerbackground section on key elements of the U.S.-South Korea relationship. The end of thereport provides a list of CRS products on South Korea and North Korea.Developments in Late 2013/Early 2014Since late 2008, relations between the United States and South Korea (known officially as theRepublic of Korea, or ROK) arguably have been at their best state since the formation of theU.S.-ROK alliance in 1953. Under South Korean President Park Geun-hye, who was inauguratedin February 2013, Seoul and Washington have continued the tight policy coordination over NorthKorea that existed between the Obama Administration and Park’s predecessor, Lee Myung-bak.Lee and Park both spoke before joint sessions of Congress, in October 2011 and May 2013,respectively. Although the overall U.S.-South Korean relationship is expected to remain healthyunder Park, she has hinted at policy moves that could test bilateral ties, particularly with respectto North Korea and the renewal of a U.S.-ROK civilian nuclear cooperation agreement.South Korea at a GlanceHead of State: President Park Geun-hye (electedDecember 2012; limited to one five-year term)Ruling Party: Saenuri (New Frontier) Party (NFP)Largest Opposition Party: Democratic Party (DP)Infant Mortality: 4.01 deaths/1,000 live births(U.S. 6.00)Fertility Rate: 1.24 children born/woman (U.S. 2.06)Literacy Rate: 98%Size: slightly larger than IndianaArable Land: 16.6%Population: 49 million (July 2013 est.) (North Korea 24.7 million)Ethnicity: homogenous (except for about 20,000 Chinese)Life Expectancy: 79.6 years (U.S. 78.49 yrs.; NorthKorea 69.2 yrs.)Nominal GDP: 1.6 trillion (2012 est.); world’s 13thlargest economy (U.S. 15.7 trillion; North Korea 40 billion)GDP Per Capita (Purchasing Power Parity): 32,400 (2012 est.) (U.S. 49,800; North Korea 1,800)Exports: 548.2 billion (2012 est.)Imports: 520.5 billion (2012 est.)Source: CIA, The World Factbook.Cooperation over North Korea Policy1Dealing with North Korea is the dominant strategic element of the U.S.-South Koreanrelationship. Park has said that her preferred policy toward to North Korea “entail[s] assuming atough line against North Korea sometimes and a flexible policy open to negotiations other times.”Some of the cooperative elements of Park’s approach toward North Korea could conflict withU.S. policy, due to an inherent tension that exists in the two countries’ views of Pyongyang: theUnited States’ predominant concern is North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction (WMD)programs, but the nuclear and long-range missile issues often competes with other issues, like1For more on North Korea issues, see CRS Report R41259, North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, andInternal Situation, by Emma Chanlett-Avery and Ian E. Rinehart; and CRS Report RL34256, North Korea’s NuclearWeapons: Technical Issues, by Mary Beth D. Nikitin.Congressional Research Service1

U.S.-South Korea Relationspromoting unification, for the top slot on South Korea’s list of priorities. Because inter-Koreanrelations have been so poor since 2008, such potential contradictions between U.S. and SouthKorean interests have not been exposed.Indeed, since Park’s inauguration, the two allies have continued the close cooperation on NorthKorea policy that was a hallmark of the relationship under Park’s predecessor, Lee Myung-bak(2008-2013). Both Seoul and Washington have emphasized deterrence in the face of a series ofactions by North Korea, including Pyongyang’s February 2013 nuclear test (its third since 2006),evidence of further progress in North Korea’s missile capabilities, and Pyongyang’s unusuallybellicose rhetoric threatening South Korea. Park has pledged to retaliate militarily if North Koreaattacks, as it did in 2010, and in 2013 Seoul and Washington ironed out a counter-provocationplan.2 With U.S. support, Park also refused to abide by North Korea’s terms for restarting theinter-Korean Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC), which ceased operation in early April 2013after Pyongyang withdrew the 50,000-plus North Korean workers employed at the complex.North Korea eventually relented, allowing the KIC to re-open in September 2013 and agreeing tosome of South Korea’s longstanding requests, such as allowing access to the Internet andadopting an electronic system to ease South Koreans’ entry into and out of the complex.Furthermore, Park repeatedly has identified North Korea’s refusal to dismantle its nuclearweapons program as a threat to South Korea and has linked large-scale aid to progress in thedenuclearization process.The experience of this close coordination in 2013 appears to have deepened the reservoir of trustbetween the two governments, to the point that the Obama Administration appears comfortablewith letting Park take the lead in trying to encourage more cooperative behavior from Pyongyang.She has called for creating a new era of peace on the Korean Peninsula and has proposed somemodest confidence-building measures with Pyongyang designed to build trust between the twosides. Most notably, as part of her “trustpolitik,” her government has delinked humanitarianassistance from other diplomatic developments, and has offered small-scale bilateral assistanceand allowed South Korean non-governmental groups to operate in North Korea. During periodswhen North Korea has moderated its behavior and reached out to South Korea, Park’sgovernment has tried to restart the program of temporary reunions for families separated since theKorean War ended in 1953.An issue for the Obama Administration and Congress is to what extent they will support—or, notoppose—Park’s possible inter-Korean initiatives. For instance, Park has indicated a desire tosomeday internationalize and expand the KIC, which several Members of Congress haveopposed. These moves could clash with legislative efforts in Congress to expand U.S. sanctionsagainst North Korea, such as H.R. 1771, the North Korea Sanctions Enforcement Act. Thus far,Administration officials have expressed support for Park’s trustpolitik approach. (For more oncooperation over North Korea, see the “North Korea in U.S.-ROK relations” section.)2In March 2010, a South Korean naval vessel sank in the Yellow Sea. Over 40 ROK sailors died. A multinationalinvestigation led by South Korea determined that the vessel was sunk by a North Korean submarine. In November ofthe same year, Yeonpyeong Island was attacked by North Korean artillery, which killed four South Koreans (twoMarines and two civilians) and wounded dozens.Congressional Research Service2

U.S.-South Korea RelationsNuclear Energy Cooperation AgreementIn April 2013, the United States and South Korea announced that they had agreed to a two-yearextension of the existing bilateral civilian nuclear cooperation agreement, also known as a 123agreement, which was due to expire in March 2014.3 In January 2014, Congress passed S. 1901,which authorized the extension. For years, talks between South Korea and the United States werenot able to resolve disagreement over how to treat fuel-making technologies in a renewed accord,and therefore the two countries decided to allow for more negotiating time. The two-yearextension is considered a temporary solution to avoid any disruption to nuclear trade. A lapsecould have affected exports of U.S. nuclear materials and reactor components to Korea, and couldpotentially affect ongoing construction of South Korean reactors in the United Arab Emirates, forwhich U.S. companies are providing components and services.One point of disagreement in the renewal process is whether South Korea will press the UnitedStates to include a provision that would allow for the reprocessing of its spent fuel. The SouthKorean government is reportedly also seeking confirmation in the renewal agreement of its rightto enrichment technology. The current U.S.-Korea nuclear cooperation agreement, as with otherstandard agreements,4 requires U.S. permission before South Korea can reprocess U.S.-originspent fuel, including spent fuel from South Korea’s U.S.-designed reactors.5 The issue hasbecome a sensitive one for many South Korean officials and politicians, who see it as a matter ofnational sovereignty. The United States has been reluctant to grant such permission due toconcerns over the impact on negotiations with North Korea and on the nonproliferation regimeoverall. Through reprocessing, spent fuel can be used to make reactor fuel or to acquireplutonium for weapons. For many years, the United States and South Korea have worked on jointresearch and development projects to address spent fuel disposition, including joint research onpyro-processing, a type of spent fuel reprocessing. In October 2010, the two countries began a 10year, three-part joint research project on pyro-processing that includes joint research anddevelopment at Idaho National Laboratory, development of international safeguards for thistechnology, economic viability studies, and other advanced nuclear research includingalternatives to pyro-processing for spent fuel disposal.6 (For more on the negotiations and thedebate over U.S.-ROK civilian nuclear cooperation, see the “Nuclear Energy and NonProliferation Cooperation” section below.)South Korea Expresses Interest in TPPIn the fall of 2013, after months of speculation, the South Korean government signaled its“interest” in joining the twelve-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement3“123” refers to section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act (as amended). Full text of the agreement is available inlinefiles/Korea South 123.pdf.4CRS Report RS22937, Nuclear Cooperation with Other Countries: A Primer, by Paul K. Kerr and Mary Beth D.Nikitin.5Under the 1978 Nuclear Nonproliferation Act, consent rights apply to material originating in the U.S. or material thathas been fabricated into fuel or irradiated in a reactor with U.S. technology. The majority of South Korea’s spent fuelwould need U.S. consent before it could be reprocessed.6“Discussions on Korea-U.S. Joint Research on Fuel Cycle,” Press Release, Ministry of Education, Science andTechnology, Republic of Korea, April 18, 2011; “S. Korea, U.S. Agree to Start Joint Study on Nuclear FuelReprocessing,” Yonhap, April 17, 2011.Congressional Research Service3

U.S.-South Korea Relationstalks.7 The economic size and strategic importance of TPP would expand significantly if SouthKorea—East Asia’s third largest economy—enters the negotiations. One of Park’s top policyagendas is reviving the country’s economy. To this end, her government has initiated a tradestrategy of entering into more FTAs, thereby making South Korea into a “linchpin” of acceleratedeconomic integration.8 South Korea is negotiating a number of FTAs, including bilateral oneswith China, Canada, and Australia, as well as a trilateral agreement with China and Japan. TheObama Administration has “welcomed” Korea’s interest in joining the talks, though United StatesTrade Representative (USTR) officials also have indicated they will place priority on concludingan agreement with the existing members before agreeing to the entry of any new countries.Obama Administration officials also have said that their consultations over South Korea joiningthe TPP will include discussions over U.S. concerns that Seoul has not adequately implementedparts of the 2011 South Korea-US Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). Specifically, USTRofficials reportedly have identified as problematic South Korea’s imposition of a new automobileemissions tax, maintenance of barriers to cross-border transfers of financial data, and creation ofnew measures to verify the country of origin for imports such as orange juice and automobiles.9The current 12 TPP countries must reach unanimous agreement on South Korea’s entry beforeSeoul can join, and in December 2013 Korea began holding preliminary consultations with TPPmembers. The next formal step for South Korea to enter the TPP would be for the South Koreangovernment to formally announce that it is seeking to participate. Following this move, if Seoulreaches agreements with the 12 members over the terms of its entry, they would officially inviteSouth Korea to join and also initiate their domestic notification procedures. In the case of theUnited States, this latter would involve notifying Congress of an intention to enter into FTAnegotiations with South Korea after a period of 90 days.Ultimately, Congress must approve implementing legislation if a completed TPP agreement—with or without South Korea—is to apply to the United States. Additionally, during the TPPnegotiating process, Congress has a formal and informal role in influencing U.S. negotiatingpositions, including through the process of granting new trade promotion authority (TPA) to thePresident. TPA, which expired in 2007, is the authority that Congress gives to the President tonegotiate trade agreements that would receive expedited legislative consideration. In January2014, legislation to renew TPA was introduced in the House (H.R. 3830) and in the Senate (S.1900).10 (For more on U.S.-South Korean economic relations, see the “Economic Relations”section.)7The TPP negotiating parties are Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru,Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. For more on the TPP, see CRS Report R42694, The Trans-PacificPartnership (TPP) Negotiations and Issues for Congress, coordinated by Ian F. Fergusson.8Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy Press Release 436, “Korea Outlines New Trade Policy Direction,” June 25,2013.9USTR, “Statement by U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman on Korea’s Announcement Regarding the TransPacific Partnership,” November 29, 2013; World Trade Online, “U.S. Will Press Seoul on Origin Checks, DataTransfers, Auto NTBs: Cutler,” December 12, 2013.10For more on TPA, see CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in TradePolicy, by William H. CooperCongressional Research Service4

U.S.-South Korea RelationsState of the AllianceSince 2009, the two sides have accelerated steps to transform the U.S.-ROK alliance, broadeningit from its primary purpose of defending against a North Korean attack to a regional and evenglobal partnership. Joint statements issued from a series of high-level meetings emphasized thecommitment to modernize and expand the alliance while reaffirming the maintenance of currentU.S. troop levels on the peninsula and the U.S. security guarantee to protect South Korea. Spurredby violent attacks from North Korea in 2010, the alliance partners agreed on a “CounterProvocation Plan” and then sharpened the agreement by developing a “Tailored DeterrenceStrategy against North Korean Nuclear and Other WMD Threats.” A high-level joint statement inOctober 2013 committed both sides to improving their missile defense systems.Despite these indicators of strength, the alliance faces a host of significant challenges in themonths and years ahead. The political atmospherics of the alliance have been positive, but theconservative Park and Lee governments have slowed significantly the defense budget increasesplanned under the earlier, progressive Roh Moo-hyun Administration (2003-2008). The twocountries also must make decisions about the realignment of U.S. forces within Korea, a processthat Congress has followed closely because of concerns about the cost. A 2007 agreement totransfer wartime operational control (Opcon) from U.S. to ROK forces by 2015 has resurfaced asa point of controversy. Reportedly, the South Korean defense establishment wants to delay theOpcon transfer to a later year, when the ROK military is better prepared to handle the commandresponsibilities in the event of war with North Korea.11 In addition, the planned realignment of allU.S. forces from bases near the de-militarized zone (DMZ) border with North Korea to basesfarther south is under review. The commander of U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) has indicated thatsome “residual” staff may continue to fulfill the so-called “tripwire” function of U.S. forcesstationed near the DMZ.12In January 2014, the two sides agreed to terms for the next five-year Special Measures Agreement(SMA), under which South Korea offsets some of the costs of stationing U.S. forces in Korea.Under the new agreement, which is subject to approval by the Korean National Assembly, Seoulwill raise its contribution by 6% to 867 million in 2014 and then increase its annual payments atthe rate of inflation. The new SMA also makes U.S. use of South Korean funds more transparentthan in the past, in response to South Korean criticism, though opposition lawmakers are notwholly satisfied with the new arrangement. (For more on alliance issues, including congressionalactions, see the “Security Relations and the U.S.-ROK Alliance” section.)Background on U.S.-South Korea RelationsOverviewWhile the U.S.-South Korea relationship is highly complex and multifaceted, five factorsarguably drive the scope and state of relations between the two allies:11Craig Whitlock, “Handover of U.S. Command of South Korean Troops Still Under Debate,” Washington Post,September 29, 2013.12Ser Myo-ja, “USFK May Keep Tripwire Function,” Korea JoongAng Daily, November 26, 2013.Congressional Research Service5

U.S.-South Korea Relations the challenges posed by North Korea, particularly its weapons of massdestruction programs and perceptions in Washington and Seoul of whether theKim Jong-un regime poses a threat, through its belligerence and/or the risk of itscollapse; the growing desire of South Korean leaders to use the country’s middle powerstatus to play a larger regional and, more recently, global role; China’s rising influence in Northeast Asia, which has become an increasinglyintegral consideration in many aspects of U.S.-South Korea strategic andeconomic policymaking; South Korea’s transformation into one of the world’s leading economies—with astrong export-oriented industrial base—which has led to an expansion of tradedisputes and helped drive the two countries’ decision to sign a free tradeagreement; and South Korea’s continued democratization, which has raised the importance ofpublic opinion in Seoul’s foreign policy.Additionally, while people-to-people ties generally do not directly affect matters of “high”politics in bilateral relations, the presence of over 1.2 million Korean-Americans and thehundreds of thousands of trips taken annually between the two countries has helped cement thetwo countries together.Members of Congress tend be interested in South Korea-related issues because of bilateralcooperation over North Korea, a desire to oversee the management of the U.S.-South Koreaalliance, South

(2008-2013). Both Seoul and Washington have emphasized deterrence in the face of a series of actions by North Korea, including Pyongyang’s February 2013 nuclear test (its third since 2006), evidence of further progress in North Korea’s missile capabilities, and Pyongyang’s unusually bellicose rhetoric threatening South Korea.

·Hyun Chang Lee, Wonkwang University, Korea ·Chul Hong Kim, Chonnam National University, Korea ·Seong Kwan Lee, Kyunghee University, Korea ·Jung Man Seo, Korea National University of Welfare, Korea ·Jun Hyeog Choi, Kimpo College, Korea ·Young Tae, Back, Kimpo College, Korea ·Kwang Hyuk Im, PaiChai University, Korea

North Korea became a Communist state under the influence of the Soviet Union while South Korea allied themselves with the United States and became a republic. Military confrontations continued along the border and in 1950, North Korea attacked South Korea. The U.N. sent military support to South Korea while China did the same in North Korea.

Korea University Business School Fact Sheet for Student Exchange Program Contact Mailing Address International Office Korea University Business School A304, Korea University Business School Main Building 145 Anam-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, Korea 02841 Telephone & Fax Tel: 82-2-3290-5362 Fax: 82-2-3290-5368 Websites Korea University korea.ac.kr

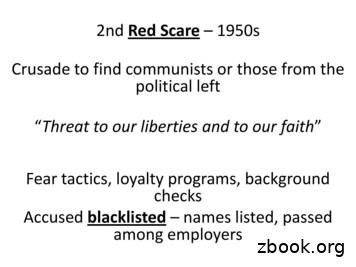

Red Scare political cartoons . Korean War (June 1950-July 1953) Japan controlled Korea – after WW2, Korea divided at 38th parallel USSR - North Korea US – South Korea June 25, 1950 – N. Korea invaded S. Korea . UN and US sends troops – Truman appoints General

KOREA PHARM 2014 10(Tue.) 13(Fri.) June 2014 KINTEX, KOREA KOREA PHARM, Korea's representing Pharmaceutical Exhibition On behalf of Organizer, we cordially invite you to KOREA PHARM 2014 to be held on June 10 13,

History of Water Sommelier Certification. To be Water Sommelier in South Korea. Water Sommelier History in Korea - For increasing tap water drinking rate, K-Water which is Korea Water Resource Government Corporation got help from KISA (Korea International Sommelier Association) and made water sommelier education course in 2011

Seoul National University Seoul, South Korea jaeminyoo@snu.ac.kr Yejun Soun Seoul National University DeepTrade Inc. Seoul, South Korea sony7819@snu.ac.kr Yong-chan Park Seoul National University Seoul, South Korea wjdakf3948@snu.ac.kr U Kang Seoul National University DeepTrade Inc. Seoul, South Korea ukang@snu.ac.kr ABSTRACT

ABR ¼ American Board of Radiology; ARRS ¼ American Roentgen Ray Society; RSNA ¼ Radiological Society of North America. Table 2 Designing an emergency radiology facility for today Determine location of radiology in the emergency department Review imaging statistics and trends to determine type and volume of examinations in emergency radiology Prepare a comprehensive architectural program .