Child Well-being In Rich Countries - Unicef-irc

UNICEFOffice of ResearchInnocenti Report Card 11Child well-beingin rich countriesA comparative overview

Innocenti Report Card 11 was written by Peter Adamson.The UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti would like to acknowledgethe generous support for Innocenti Report Card 11 provided by theAndorran and Swiss National Committees for UNICEF, and theGovernment of Norway.Any part of this Innocenti Report Card may be freely reproduced usingthe following reference:UNICEF Office of Research (2013). ‘Child Well-being in Rich Countries:A comparative overview’, Innocenti Report Card 11, UNICEF Office ofResearch, Florence.The Report Card series is designed to monitor and compare theperformance of economically advanced countries in securing therights of their children.In 1988 the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) established aresearch centre to support its advocacy for children worldwide and toidentify and research current and future areas of UNICEF’s work. Theprime objectives of the Office of Research are to improve internationalunderstanding of issues relating to children’s rights, to help facilitatefull implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Childsupporting advocacy worldwide. The Office aims to set out acomprehensive framework for research and knowledge within theorganization in support of its global programmes and policies. Throughstrengthening research partnerships with leading academic institutionsand development networks in both the North and South, the Officeseeks to leverage additional resources and influence in support ofefforts towards policy reform in favour of children.Publications produced by the Office are contributions to a global debateon children and child rights issues and include a wide range ofopinions. For that reason, some publications may not necessarily reflectUNICEF policies or approaches on some topics. The views expressedare those of the authors and/or editors and are published in order tostimulate further dialogue on child rights.Cover photo luxorphoto/Shutterstock United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), April 2013ISBN: 978-88-6522-016-0ISSN: 1605-7317UNICEF Office of Research – InnocentiPiazza SS. Annunziata, 1250122 Florence, ItalyTel: 39 055 2033 0Fax: 39 055 2033 220florence@unicef.orgwww.unicef-irc.org

UNICEFOffice of ResearchInnocenti Report Card 11Child well-beingin rich countriesA comparative overviewPART ONE presents a league table of child well-beingin 29 of the world’s advanced economies.PART TWO looks at what children say about theirown well-being (including a league table ofchildren’s life satisfaction).PART THREE examines changes in child well-beingin advanced economies over the first decade of the2000s, looking at each country’s progress ineducational achievement, teenage birth rates,childhood obesity levels, the prevalence of bullying,and the use of tobacco, alcohol and drugs.

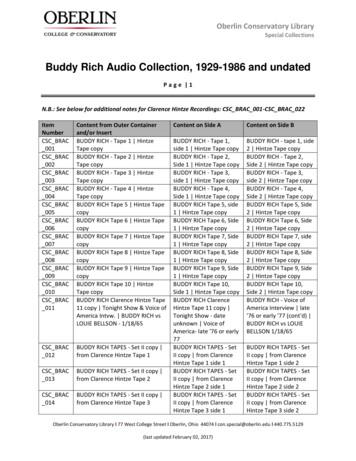

2I n n o c e n t iR e p o r tC a r dPART 1A league table of child well-beingThe table below ranks 29 developed countries according to the overall well-being of their children. Each country’s overall rank isbased on its average ranking for the five dimensions of child well-being considered in this review.A light blue background indicates a place in the top third of the table, mid blue denotes the middle third, and dark blue the bottom third.Overall well-beingDimension 1Dimension 2Dimension 3Dimension 4Dimension 5Average rank(all 5 dimensions)Materialwell-beingHealth andsafetyEducationBehavioursand risksHousing 12Slovenia12865212013France12.8101015131614Czech ed e23.4201928252526United via26.4282820282829Romania28.62929292729Lack of data on a number of indicators means that the following countries, although OECD and/or EU members, could not be included in the league tableof child well-being: Australia, Bulgaria, Chile, Cyprus, Israel, Japan, Malta, Mexico, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, and Turkey.1 1

I n n o c e n t iR e p o r tC a r d1 13IntroductionThe league table opposite presentsthe latest available overview of childwell-being in 29 of the world’s mostadvanced economies.Five dimensions of children’s liveshave been considered: materialwell-being, health and safety,education, behaviours and risks, andhousing and environment. In total,26 internationally comparableindicators have been included in theoverview (see Box 1).The table updates and refines thefirst UNICEF overview of child wellbeing published in 2007 (ReportCard 7) .i Changes in child well-beingover the first decade of the 2000sare examined in Part 3.Key findings»»The Netherlands retains itsposition as the clear leader andis the only country ranked amongthe top five countries in alldimensions of child well-being.The Netherlands is also theclear leader when well-being isevaluated by children themselves– with 95% of its children ratingtheir own lives above the midpoint of the Life Satisfaction Scale(see Part 2).»»»The bottom four places in thetable are occupied by three ofthe poorest countries in thesurvey, Latvia, Lithuania andRomania, and by one of therichest, the United States.Overall, there does not appearto be a strong relationshipbetween per capita GDP andoverall child well-being. TheCzech Republic is ranked higherthan Austria, Slovenia higherthan Canada, and Portugalhigher than the United States.There are signs that thecountries of Central and EasternEurope are beginning to closethe gap with the moreestablished industrial economies(see Part 3).Change over a decadeAlthough changes in methods andstructure make it difficult to makecomparisons between the first twoissues of the UNICEF overview ofchild well-being (see Part 3) it isnonetheless clear that there havebeen some significant changes overthe first decade of the 2000s.»Overall, the story of the firstdecade of the 2000s is one ofwidespread improvement inmost, but not all, indicators ofchildren’s well-being. The ‘lowfamily affluence’ rate, the infantmortality rate, and the percentageof young people who smokecigarettes, for example, havefallen in every single country forwhich data are available.Data sources and background papersThe data sources used for this report are set out in the three backgroundpapers detailed below and available at http://www.unicef-irc.orgMartorano, B., L. Natali, C. de Neubourg and J. Bradshaw (2013). ‘Child Wellbeing in Advanced Economies in the Late 2000s’, Working Paper 2013-01.UNICEF Office of Research, f/iwp 2013 1.pdf»Four Nordic countries – Finland,Iceland, Norway and Sweden – sitjust below the Netherlands at thetop of the child well-being table.Martorano, B., L. Natali, C. de Neubourg and J. Bradshaw (2013). ‘Child Wellbeing in Economically Rich Countries: Changes in the first decade of the 21stcentury’, Working Paper 2013-02. UNICEF Office of Research, f/iwp 2013 2.pdf»Four southern European countries– Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain– are placed in the bottom half ofthe table.Bradshaw, J., B. Martorano, L. Natali and C. de Neubourg (2013). ‘Children’sSubjective Well-being in Rich Countries’, Working Paper 2013-03. UNICEFOffice of Research, f/iwp 2013 3.pdf

4I n n o c e n t i»Spain has slipped down therankings – from 5th out of 21countries in the early years ofthe decade to 19th out of 29countries in 2009/2010.»The United Kingdom has risenup the rankings from bottomplace (21st out of 21 countries)in 2000/2001 to a mid-tableposition today.Part 3 of this report examineschanges over the first decade ofthe 2000s in more detail.Measuring progress for childrenThe league table of child well-beingis designed to measure andcompare progress for childrenacross the developed world. Itspurpose is to record the standardsachieved by the most advancednations and to contribute to debatein all countries about how suchstandards might be achieved.As a moral imperative, the need topromote the well-being of childrenis widely accepted. As a pragmaticimperative, it is equally deservingof priority; failure to protect andpromote the well-being of childrenis associated with increased riskacross a wide range of later-lifeoutcomes. Those outcomes rangefrom impaired cognitivedevelopment to lower levels ofschool achievement, from reducedskills and expectations to lowerproductivity and earnings, fromhigher rates of unemployment toincreased dependence on welfare,from the prevalence of antisocialbehaviour to involvement in crime,from the greater likelihood of drugand alcohol abuse to higher levels ofteenage births, and from increasedhealth care costs to a higherincidence of mental illness.ii, iiiThe case for national commitmentto child well-being is thereforecompelling both in principle and inpractice. And to fulfil thatcommitment, measuring progressin protecting and promoting thewell-being of children is essential topolicy-making, to advocacy, to thecost-effective allocation of limitedresources, and to the processes oftransparency and accountability.International comparabilityThe measurement of child wellbeing, however, is a relatively newarea of study and the overviewpresented here remains a work inprogress. Chief among itslimitations is the fact thatinternationally comparable data onchildren’s lives are not sufficientlytimely. Between the collection ofdata in a wide variety of differentsettings and their publication inquality-controlled, internationallycomparable form the time-lag istypically two to three years. Thismeans that most of the statistics onchild well-being used in this report,though based on the latest availabledata, apply to the period 2009–2010. Such a delay would befrustrating at the best of times. Butthe last three years have been farfrom the best of times. Beginningin late 2008, economic downturnin many developed nations hasseen rising unemployment and fallsin government expenditures whichcannot but affect the lives of manymillions of children. Data from2009 and 2010 capture only thebeginning of this turbulence.Nonetheless, for the most part,the data used in this overview tracklong-term trends and reflect theresults of long-term investments inchildren’s lives. Average levels ofR e p o r tC a r d1 1school achievement, orimmunization rates, or theprevalence of risk behaviours,for example, are not likely to besignificantly changed in the shortterm by the recessions of the lastthree years.For the time being, it must beaccepted that data-lag is part ofthe entry price for internationalcomparisons of child well-being.And although national-levelmonitoring of children’s lives is themore important task, UNICEFbelieves that internationalcomparison can also play a part.It is international comparison thatcan show what is achievable in thereal world, highlight strengths andweaknesses in individual countries,and demonstrate that child wellbeing is policy-susceptible. And itis international comparison thatcan say to politicians, press andpublic everywhere – ‘This is howyour performance in protectingchildren compares with the recordof other nations at a similar levelof development.’Finally, any single overview of acomplex and multidimensionalissue carries a risk of hiding morethan it reveals. The following pagestherefore set out to make thisoverview of child well-being astransparent as possible byexamining each of its dimensionsin turn.

I n n o c e n t iR e p o r tC a r d1 15Box 1 How child well-being is measuredThe table below shows how the overview of child well-being has been constructed and sets out the full list ofindicators used. The score for each dimension has been calculated by averaging the scores for each component.Similarly, component scores are arrived at by averaging the scores for each indicator.DimensionsComponentsDimension 1Material well-beingFigure 1.0Monetary deprivationDimension 2Health and safetyFigure 2.0Health at birthDimension 3EducationFigure 3.0Relative child poverty rate1.1a1.1bChild deprivation rate1.2aLow family affluence rate1.2bInfant mortality rate2.1aLow birthweight rate2.1bPreventive health servicesOverall immunization rate2.2Childhood mortalityChild death rate, age 1 to 192.3Participation rate: early childhoodeducation3.1aParticipation rate: further education,age 15–193.1bNEET rate (% age 15–19 not ineducation, employment or training)3.1cAverage PISA scores in reading,maths and science3.2Being overweight4.1aEating breakfast4.1bEating fruit4.1cMaterial deprivationParticipationHealth behavioursRisk behavioursExposure to violenceDimension 5Housing and environmentFigure 5.0Figure no.Relative child poverty gapAchievementDimension 4Behaviours and risksFigure 4.0IndicatorsHousingEnvironmental safetyTaking exercise4.1dTeenage fertility 4.3aBeing bullied4.3bRooms per person5.1aMultiple housing problems5.1bHomicide rate5.2aAir pollution5.2b

6I n n o c e n t iR e p o r tC a r d1 1Dimension 1 Material well-beingFigure 1.0 An overview ofchildren’s material well-beingNetherlandsFinlandThe league table of children’s materialwell-being shows each country’sperformance in relation to the averagefor the 29 developed countries underreview. The table is scaled to showeach country’s distance above orbelow that iaThe length of each bar shows eachcountry’s distance above or below theaverage for the group as a whole. Theunit of measurement is the ‘standarddeviation’ – a measure of the spreadof scores in relation to the ed KingdomCanadaCzech talySpainSlovakiaUnited .0-0.50.00.51.01.5Assessing material rivationIND I C ATOR SRelative child poverty rate (% of children livingin households with equivalent incomes below50% of national median)Child poverty gap (distance between nationalpoverty line and median incomes of householdsbelow poverty line)Index of child deprivation (% of children lackingspecific items)Family affluence scale (% of children reportinglow family affluence)

I n n o c e n t iR e p o r tC a r d1 17Children’s material well-beingThe table opposite (Figure 1.0)presents an overview of children’smaterial well-being in developedcountries. Overall, it suggests thatmaterial well-being is highest inthe Netherlands and in the fourNordic countries and lowest inLatvia, Lithuania, Romania and theUnited States.Two components of material wellbeing have been considered inarriving at this overview – relativeincome poverty and materialdeprivation. The strengths andweaknesses of both measures werediscussed in detail in the previousreport in this series (Report Card 10)ivwhich argued that both measures arenecessary to achieve a rounded viewof children’s material well-being.Relative poverty:child poverty ratesTwo separate indicators havebeen used to measure monetarydeprivation. They are the relativechild poverty rate (Figure 1.1a) andthe ‘child poverty gap’ (Figure 1.1b).The relative child poverty rate showsthe proportion of each nation’sFigure 1.1a Relative child poverty rates% of children aged 0–17 living in households with equivalent incomesbelow 50% of national h RepublicUnited ted StatesRomaniaCyprusMaltaAustraliaNew ZealandJapanBulgariaCountries with grey bars have not beenincluded in the ranking tables, or in theoverall league table of child well-being,as they have data for fewer than 75% ofthe total number of indicators used.0children living in households wheredisposable income is less than 50%of the national median (after takingtaxes and benefits into accountand adjusting for family size andcomposition). This is the definitionof child poverty used by themajority of the world’s developedeconomies. Broadly speaking, itshows the proportion of childrenwho are to some significant extent5101520Findings»Finland is the only country with a relative child poverty rate of lessthan 5% and heads the league table by a clear margin of more thantwo percentage points.»The countries in the top half of the league table all have relative childpoverty rates of less than 10%.»Four southern European countries – Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain –have child poverty rates higher than 15% (along with Latvia, Lithuania,Romania and the United States).25

8I n n o c e n t iGap between the poverty line and the median income of thosebelow the poverty line – as % of the poverty adaUnited KingdomCzech toniaSlovakiaRomaniaItalyIrelandLithuaniaUnited StatesSpain1 1Relative poverty:the poverty gapThe relative child poverty rates inFigure 1.1a show what percentageof children live below each nation’srelative poverty line. But they revealnothing about how far below thatline those children are beingallowed to fall. To gauge the depthof relative child poverty, it is alsonecessary to look at the ‘childpoverty gap’ – the distance betweenthe poverty line and the medianincomes of those below the line.Figure 1.1b shows this ‘childpoverty gap’ for each country.Considering ‘rate’ and ‘gap’ togethershows six countries in the bottomthird of both tables. They are Italy,Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Spainand the United States. By contrast,there are also six countries thatfeature in the top third of bothtables – Austria, Finland,Netherlands, Norway, Sloveniaand Sweden.CyprusMaltaAustraliaNew ZealandJapanBulgaria0510152025303540Findings»C a r dexcluded from the advantages andopportunities which most childrenin that particular society wouldconsider normal.Figure 1.1b Child poverty gaps»»R e p o r tHungary and Luxembourg have the smallest child poverty gaps.Denmark is an exception among Nordic countries in having a high childpoverty gap (almost 30%). Only a small proportion of Danish children(6.3%) fall below the country’s relative poverty line; but those who do,fall further below than in most other countries.Several countries have allowed the child poverty gap to widen to morethan 30%. They are Bulgaria, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Romania,Slovakia, Spain and the United States.What this means for the childrenof Spain or the United States, forexample, is that 20% or more fallbelow the relative poverty line andthat, on average, they fall almost40% below that line. In theNetherlands or Austria, on the otherhand, 6% to 8% of children fallbelow the relative poverty line and,on average, they fall approximately16% below.Taken together, these two childpoverty indicators – the rate and thegap – make up the relative incomecomponent of children’s materialwell-being.

I n n o c e n t iR e p o r tC a r d1 1Material deprivation:the Child Deprivation Index9example, does not mean thatchildren’s actual living standards arelower in Canada (only that a greaterproportion of Canadian children livein households where disposableincome is 50% of the median). Inorder to arrive at a more completepicture of child poverty, a measureof actual material deprivation hastherefore also been included.Relative income measures, however,have little to say about the

Any part of this Innocenti Report Card may be freely reproduced using the following reference: UNICEF Office of Research (2013). ‘Child Well-being in Rich Countries: A comparative overview’, Innocenti Report Card 11, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence. The Report Card series is designed to monitor and compare the performance of economically advanced countries in securing the rights of .

Care needed: (check all that apply) Child #1 Child #2 Child #3 Child #4 Child #5 Preferred Location (Zip Code other than home) Full day Part day Evenings Overnight Weekends Special Needs: Child #1 Child #2 Child #3 Child #4 Child #5 Limited English Child Protective Services Severely Handicapped

Robert T. Kiyosaki & Sharon L. Lechter Rich Dad Poor Dad What the Rich Teach Their Kids About Money that the Poor and Middle Class Do Not Rich Dad’s CASHFLOW Quadrant Rich Dad’s Guide to Financial Freedom Rich Dad’s Guide to Investing What the Rich Invest In that the Poor and Middle Class Do Not Rich Dad’s Rich Kid Smart Kid

Best-selling Books by Robert T. Kiyosaki Rich Dad Poor Dad What the Rich Teach eir Kids About Money at the Poor and Middle Class Do Not Rich Dad s CASHFLOW Quadrant Guide to Financial Freedom Rich Dad s Guide to Investing What the Rich Invest in at the Poor and Middle Class Do Not Rich Dad s Rich Kid Smart Kid

like my child-Exactly like my child) My child enjoys sharing his/her things with others. My child does nice things for others without being asked. (Strongly agree-Strongly disagree) When my child helps out a friend, he/she expects something in return. If needed, my child is willing to he

BUDDY RICH/MEL TORME @ Palace Theater, Cleveland OH 10/25/77 Tape 1 COPY BUDDY RICH/MEL TORME @ Palace Theater, Cleveland, OH 10/25/77 tape 1, side 1 COPY BUDDY RICH/MEL TORME tape 1 cont'd COPY CSC_BRAC _031 BUDDY RICH BIG BAND 1.w/Mel Torme @ Palace Thtr, Cleve, Oh 10/25/77 tape 2 2. Jacksonville Jazz 10/14/83 COPY BUDDY RICH/MEL

belonged to my rich dad. My poor dad often called my rich dad a "slum lord" who exploited the poor. My rich dad saw himself as a "provider of low income housing." My poor dad thought my rich dad should give the city and state his land for free. My rich dad wanted a good price for his land. 5

Child: The United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child defines a child as a human being younger than 18, unless majority under the law applicable to the child is attained earlier. Child abuse: Child abuse is any deliberate behavior or

2 Hennepin County Child Well-Being annual report: 2021 Introduction Since 2017, the Child Well-Being Advisory Committee has supported an ongoing transformation of county services and supports for children and families. This work started in the child protection system, with six major system improvement recommendations