Review Of Current And Planned Adaptation Action In Botswana

Review of Current andPlanned AdaptationAction in BotswanaCARIAA Working Paper #7Alec Crawford

CARIAA Working Paper #7Crawford, A. 2016. Review of current and planned adaptation action in Botswana. CARIAAWorking Paper no. 7. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada and UK Aid,London, United Kingdom. Available online at: www.idrc.ca/cariaaISSN: 2292-6798This CARIAA working paper has been prepared by the International Institute for SustainableDevelopment (IISD).About CARIAA Working PapersThis series is based on work funded by Canada’s International Development Research Centre(IDRC) and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) through theCollaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA). CARIAA aims tobuild the resilience of vulnerable populations and their livelihoods in three climate change hotspots in Africa and Asia. The program supports collaborative research to inform adaptation policyand practice.Titles in this series are intended to share initial findings and lessons from research andbackground studies commissioned by the program. Papers are intended to foster exchange anddialogue within science and policy circles concerned with climate change adaptation invulnerability hotspots. As an interim output of the CARIAA program, they have not undergone anexternal review process. Opinions stated are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflectthe policies or opinions of IDRC, DFID, or partners. Feedback is welcomed as a means tostrengthen these works: some may later be revised for peer-reviewed publication.ContactCollaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asiac/o International Development Research CentrePO Box 8500, Ottawa, ONCanada K1G 3H9Telephone: ( 1) 613-236-6163; Email: cariaa@idrc.caCreative Commons LicenseThis Working Paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 4.0 International License. Articles appearing in this publication may be freely quotedand reproduced provided that i) the source is acknowledged, ii) the material is not used forcommercial purposes, and iii) any adaptations of the material are distributed under the samelicense. 2016 International Development Research CentreCover photos:Top: PANOS/Jean-Leo DugastBottom: PANOS/Abbie Trayler-SmithLeft: Blane Harvey

CARIAA Working Paper #7AbstractClimate change presents a very real challenge to Botswana’s continued development andrelative prosperity. An increasing population and growing demand for water — fromresidential, commercial, and industrial sources, including mining — will interact withdeclining rainfall, rising temperatures, and increased rates of evapotranspiration across muchof the country to exacerbate water scarcity and other existing vulnerabilities. Botswana is lessvulnerable to the impacts of climate change than its neighbours due to its higher developmentstatus and associated readiness to address the impacts of climate change, rather than becauseof its level of exposure to climate change or its policy environment. Nevertheless, thecountry’s climate vulnerability is closely tied to its existing high level of water scarcity. Thegovernment of Botswana has identified five key sectors as particularly vulnerable: water,health, crops, grasslands and livestock, and forestry. However, the government does notconsider climate change a national priority, and the subsequent lack of guiding policy,legislation, and strategy on responding to the impacts of climate change, as well as a dearth ofadaptation programs and projects within the country, will only exacerbate existing andexpected climate-related threats. This report explores these issues in greater depth. It is onein a series of country reviews prepared to provide the Collaborative Adaptation ResearchInitiative in Africa and Asia with a snapshot of adaptation action in its countries ofengagement.iii

CARIAA Working Paper #7RésuméLes changements climatiques représentent un véritable obstacle au développement continu età la relative prospérité du Botswana. L’augmentation de la population et la hausse des besoinsen eau dans les zones résidentielles, commerciales et industrielles, notamment des besoins dusecteur minier, se heurtent à la baisse des précipitations, à la hausse des températures et à lahausse du taux d’évapotranspiration dans la quasi-totalité du pays, ce qui exacerbe la pénuried’eau et d’autres vulnérabilités existantes. Le Botswana est moins vulnérable aux effets deschangements climatiques que ses voisins en raison de son niveau de développement plusélevé et de sa disposition à s’attaquer aux effets des changements climatiques, plutôt que dufait de son niveau d’exposition aux changements climatiques ou de ses politiques. Cependant,la vulnérabilité du pays aux changements climatiques est étroitement liée à l’importantepénurie d’eau à laquelle il fait face actuellement. Le gouvernement du Botswana a déterminécinq principaux secteurs particulièrement vulnérables : l’eau, la santé, les cultures, lespâturages et l’élevage, et la foresterie. Cependant, le gouvernement ne considère pas leschangements climatiques comme une priorité nationale, et le manque de politique directrice,de législation et de stratégie de lutte contre les effets des changements climatiques qui endécoule, ainsi que l’absence de programmes et de projets d’adaptation dans le pays ne ferontqu’exacerber les menaces existantes et prévues liées au climat. Ce rapport examine cesquestions plus en détail. Cet examen fait partie d’une série d’examens des pays préparés dansle cadre de l’Initiative de recherche concertée sur l’adaptation en Afrique et en Asie quidonnent un aperçu des mesures d’adaptation dans les pays où elle est déployée.iv

CARIAA Working Paper #7AcronymsBOCONGOBotswana Council of Non-Governmental OrganizationsCARIAACollaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and AsiaDFIDDepartment for International DevelopmentDMSDepartment of Meteorological ServicesHDRHuman Development ReportIPCCIntergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeCCADRRDWAIDRCIWRMclimate change adaptationdisaster risk reductionDepartment of Water AffairsInternational Development Research Centreintegrated water resources managementMEWTMinistry of Environment, Wildlife and TourismMoAMinistry of AgricultureMFDPND-GAINNDMONDPMinistry of Finance and Development PlanningNotre Dame Global Adaptation IndexNational Disaster Management OfficeNational Development PlanNPCWTNRCC National Portfolio Committee on Wildlife, Tourism, Natural Resources andClimate ChangeOECDOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentTITransparency InternationalSNCUNDPUNFCCCSecond National Communication to the United Nations FrameworkConvention on Climate ChangeUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations Framework Convention on Climate Changev

CARIAA Working Paper #7USAIDUnited States Agency for International Developmentvi

CARIAA Working Paper #7About the authorsAlec CrawfordAssociate, International Institute for Sustainable DevelopmentToronto, CanadaAlec Crawford is a researcher with the CARIAA-supported review of current and plannedadaptation in the CARIAA program’s countries of focus. His research examines the linksamong environmental change, natural resources, conflict and peacebuilding in fragile states.Contact: alec.crawford@iisd.cavii

CARIAA Working Paper #7AcknowledgementsI am grateful to Jo-Ellen Parry for her leadership and guidance in the development of thisreport, and to Anika Terton for her thorough research support. I also thank the CARIAA teamfor their input and feedback.viii

CARIAA Working Paper #7ContentsAbstract. iiiRésumé.ivSynopsis . xIntroduction . 4.2Current climate and projected changes . 2Current climate . 2Observed climate trends . 3Climate projections. 4Vulnerability to climate change . 4Development profile . 4Vulnerability of key sectors . 7Vulnerable regions and groups . 8Adaptation planning context . 9National-level development policy context . 10National-level climate policy context . 11Institutional structure for climate governance . 13National-level sectoral policies. 14Current and planned adaptation programs and projects . 16Adaptation projects and programs . 16Climate finance . 18Networks and communities of practice . 20Conclusions . 21Annexes . 23References . 31ix

CARIAA Working Paper #7Synopsis1Climaterisks Rising temperatures Uncertain changes inrainfall patternsKey sources ofvulnerabilityVulnerablesectorsIllustrative potential impacts onvulnerable sectorIllustrative adaptation priority adaptation measures in each sector (from SecondNational Communication)Water Increased water demand with hottertemperatures Decreased water supply, compoundedby increased demand due topopulation growth, economicdevelopment, and increasingtemperatures Decrease in annual dam yields Average increase in unmet waterdemand Declining levels of groundwater Health Shift in malaria band westwards andsouthwards Increased child morbidity andmortality with lack of fresh and cleanwater Implement malaria control programmes Control diarrheal diseases and integrate management of childhood infections Provide social safety nets for the health sector20%Crops Changes in growing season length Decreases in crop productivity Intensify national irrigation network Promote desalination, soil-water-cropmanagement strategies, rainwater40% Water scarcity, desert landscape Poor soil fertility High reliance on groundwater resourcesand low recharge rates Continued reliance on fuel wood forsignificant portion of energy resources Reliance on food imports for food security Economic reliance on water-intensive miningactivities High rates of HIV/AIDS infection High incidence of drought Relatively low levels of gender equityImplement water conservation measures, awareness campaignsDevelop national water conservation strategyAssess water resources and scarcityDevelop programs to protect urban poor from price increasesIncrease data availability/access and documentationDiversify and increase water resources for rural areasAdopt indigenous methods of water useImplement integrated water resources management strategies Diversify crops, improve crop varieties Develop early warning systems,emergency response planningProjectsinsector 140%Percentage of total identified discrete adaptation projects and programs based upon research undertaken as part of this review. Note that individual projects may address more than one sector.x

CARIAA Working Paper #7harvesting, treated wastewater toaddress water scarcity Promote zero tillage to improve soilstructure Improve access to farm inputs andcredit, improve agricultural extensionservices Fence grazing areas for individuals orgroups Match livestock breeds to the localenvironment Diversify farm produceGrasslandsandLivestock Shift toward undesirable plants Increased livestock morbidity duringincreasingly frequent drought events Feed animals during drought (vs.grazing) Implement vaccination programs Move cattle to better pastures Introduce drought- and diseasetolerant livestock breedsForestry Thorn and shrub savannahs to expandat the expense of grasslands andmoister forests and wetlands Use less-preferred alternatives, non-indigenous supplements in the face of reducedforest products------Particularly vulnerable regionsParticularly vulnerable groupsStatus of climate governance (policies,institutions) Arid and semi-arid lands Rural populations Climate change policy and strategy beingdraftedxi

CARIAA Working Paper #7IntroductionBotswana is a sparsely populated, landlocked country in southern Africa bordered by Namibia tothe north and west, South Africa to the south, and Zimbabwe to the east.2 Most of the country isdefined as arid or semi-arid and is inhospitable to human settlement; the sands of the KalahariDesert cover three-quarters of Botswana’s land area. The Okavango River, flowing from theAngolan Highlands, floods the northwest of the country from March to August each year to form theOkavango Delta, one of the world’s largest inland deltas (see Figure 1).Since achieving independence from the British in 1966, Botswana has enjoyed decades of stablecivilian rule and democratic elections, and today boasts the highest levels of human development insub-Saharan Africa (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2014). It has achieved, or ison track to achieve, most of its Millennium Development Goals, lagging only in the areas ofimproving maternal health and reducing child mortality. The economy continues to grow at astrong pace (5.8% per year in 2015, according to the World Bank). This growth is underpinned byBotswana’s rich mineral resource deposits, in particular its large diamond reserves (the world’slargest diamond mine is inBotswana).Botswana is less vulnerable to theimpacts of climate change than itsneighbours and more ready toaddress these impacts. This is inpart a function of the country’sdevelopment status and associatedlevel of adaptive capacity, ratherthan a reflection of its exposure toclimate change or its policyenvironment. Nevertheless, climatechange presents a very realchallenge to Botswana’s continueddevelopment and relativeprosperity. Its vulnerabilities areclosely tied to the country’s existinghigh level of water scarcity. Anincreasing population andincreasing demand for water —from residential, commercial andFigure 1 – Ecoregions of Botswana. (Map courtesy of theindustrial sources, including miningUniversity of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at— will interact with decliningAustin)rainfall, rising temperatures, andincreased rates of evapotranspiration across much of the country to exacerbate water scarcity and2Botswana also shares a very short border of a few hundred metres with Zambia in the north, at Kazungula on the Zambezi River.1

CARIAA Working Paper #7other existing vulnerabilities. The government has identified five key sectors as particularlyvulnerable: water, health, crops, grasslands and livestock, and forestry. But a lack of guiding policy,legislation, and strategy on responding to the impacts of climate change, as well as a dearth ofadaptation programs and projects within the country, will further exacerbate existing and expectedclimate-related threats.These issues are explored in greater depth within this report, which provides an overview ofcurrent and planned adaptation action in Botswana. It is one in a series of country reviewsprepared to provide the Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA)with a picture of the policies, programs, and projects designed and implemented specifically toaddress the current and projected impacts of climate change in its countries of engagement. Jointlyfunded by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) and theInternational Development Research Centre (IDRC), CARIAA aims to help build the resilience ofvulnerable people to climate change in three hot spots in Africa and Asia: semi-arid areas, deltas inAfrica and South Asia, and glacier- and snow-fed river basins in the Himalayas. To achieve this goal,CARIAA is supporting four consortia to conduct high-calibre research and policy engagementactivities that will inform national and sub-national planning processes in 17 countries, includingBotswana.This report begins by describing Botswana’s current and projected exposure to climate risks.Section 3 outlines the factors that increase the vulnerability of Botswana and its people to climatechange, describing the country’s current development status and the potential implications of thesechanges for key sectors. Section 4 provides an overview of the critical policies and plans shapingBotswana’s efforts to address climate change adaptation (CCA) at the national and sub-nationallevels. Section 5 describes the scale, type, and focus of current and planned adaptation-focusedprograms and projects in Botswana, as well as the level of adaptation finance flowing into thecountry, to assess the status of efforts to address the country’s critical adaptation priorities. Section6 provides a profile of in-country efforts to advance adaptation learning and knowledge sharing, asreflected in the presence of networks and communities of practice active in this field. The paperconcludes with an assessment of the general status of adaptation planning at the national and subnational levels in Botswana.1. Current climate and projected changesThis section provides an overview of the climate risk context in Botswana, beginning with a generaldescription of the country’s current climate and eco-climatic zones, followed by discussions ofobserved trends and projected changes to its climate over the remainder of this century.1.1 Current climateBotswana has a subtropical climate that is largely defined by relatively low levels of precipitation.Most of the country is categorized as arid or semi-arid; much of it is desert and receives on averageless than 250 mm of rainfall annually. Temperature and rainfall tend to vary on annual, decadal,and multi-decadal timescales across the region, with rainfall the more variable of the two: annual2

CARIAA Working Paper #7rainfall in the centre of the country can swing from less than 100 mm in the driest years to morethan 300 mm in the wettest (Daron, 2014). The wettest part of the country is the northeast, whichreceives on average 500 mm of rain (Department of Meteorological Services [DMS], n.d; Ministry ofEnvironment, Wildlife and Tourism [MEWT], 2012). Rain typically falls in the austral summermonths, between November and March, with precipitation levels peaking in January. The dryseason, when little to no rain falls, runs from May to August (DMS, n.d.). The vast majority of thecountry’s precipitation falls in erratic, unpredictable, and localized thunderstorms. Summertemperatures range from 18oC to 32oC in January, but they can climb as high as 42oC; in thewinter, they average 21oC (July) but can dip down to 5oC (DMS, n.d.). The south and southwestexperience the lowest temperatures. This temperature range is indicative of the country’s desertecosystem, which means that temperature variations can be significant through the day, with hotdays and cooler nights (DMS, n.d.). The primary factors affecting the climate across the southernAfrica region include altitude (Botswana is on a plateau, with an average altitude of 1,000 m); thewarm Indian and cool South Atlantic oceans; the migration of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone,which largely dictates the timing and magnitude of summer rains; and the location of dominantatmospheric high- and low-pressure systems (Daron, 2014).1.2 Observed climate trendsTemperatures in Botswana have increased across all seasons and regions since 1963.Temperatures in the interior have increased between 1.6oC and 2.0oC over the past 50 years, beingmost pronounced during the dry season (MEWT, 2012). The number of cold days and nights hasdecreased, while the number of warm days and nights has increased. Drought and flooding are bothmost common in northern Botswana, which typically has been the wettest part of the country(MEWT, 2012). This region saw a decrease in summer rainfall between 1963 and 2012 (Daron,2014).Temperatures in Botswana are expected to continue to increase in the years ahead (Daron, 2014):according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Fifth Assessment Report, “itis virtually certain that there will be more frequent hot and fewer cold temperature extremes overmost land areas on daily and seasonal timescales as global mean temperatures increase” (IPCC,2013). Modeling by the IPCC for southern Africa suggests that temperatures could rise by 1.1oC by2035 (ranging from 0.6oC to 1.6oC), 2.5oC by 2065 (from 1.7oC to 3.4oC), and 4.5oC by 2100 (from3.3oC to 6.3oC) (Christensen et al., 2013, p. 14SM-36).3 The country’s Second NationalCommunication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (SNC) supportsthis trend: it expects temperatures to increase by an average of 2oC across the country by 2030,with warming most pronounced over the Kalahari in the west (MEWT, 2012).4 An increase intemperature will increase evapotranspiration across the country, which is expected to placeadditional stress on already vulnerable systems (Daron, 2014).These projections represent a 50% likelihood of occurrence, using 39 global models and the Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5scenario and against a baseline period of 1986 to 2005.4 This projection was calculated using the MAGICC/SCENGEN climate model.33

CARIAA Working Paper #71.3 Climate projectionsIt is more difficult to forecast precipitation for the country due to the combination of climaticfactors that contribute to the region’s existing climate variability. As reported in its SNC, thegovernment expects total annual rainfall to increase in the south, the country’s driest region, and todecrease in the north and east, those areas that historically have received more precipitation. Daron(2014) notes, however, that it is difficult to forecast expected changes in Botswana’s precipitationlevels due to historically inconsistent patterns for rainfall in the region; most models cannot agreeon the direction or magnitude of rainfall changes by mid-century. It is likely, however, that multidecadal variability in rainfall patterns will continue (Daron, 2014). As a result of predictedtemperature increases, the government expects droughts to increase in frequency and severity,particularly by 2080 to 2100, with the largest changes experienced in western and northernBotswana (MEWT, 2012).2. Vulnerability to climate changeThe vulnerability of Botswana’s population, its economy, and its environment to climate change willbe determined by the nature of the changes to which they are exposed and by national capacities tomanage, recover from, and adapt to these changes. This section introduces and explores theeconomic, political, demographic, social, and environmental factors within Botswana that influenceits adaptive capacity. It also includes an assessment of the implications of these changes for keyeconomic sectors within Botswana.2.1 Development profileBotswana is categorized as a country that has achieved a level of medium human development; aspresented in Table 1, in the most recent Human Development Report of the United NationsDevelopment Programme (UNDP), the country ranked 109th out of 187 countries (UNDP, 2014).This makes Botswana the most developed country in continental sub-Saharan Africa. The countryachieved the Millennium Development Goal of halving its population living in conditions of extremehunger and poverty in 2007. It has also achieved, or is likely to achieve, its targets for universalprimary education, promoting gender equality, combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases,ensuring environmental sustainability, and developing a global partnership for development(UNDP, 2012). Where Botswana continues to lag is in efforts to reduce child mortality rates and toimprove maternal health (UNDP, 2012).Botswana is one of the world’s most sparsely populated countries, with a population of just 2million that is growing at a rate of 0.9% per year (UNDP, 2014). Nearly two-thirds of the populationlives in Botswana’s cities, which is in part a function of the country’s environment: nearly threequarters of Botswana is covered by the inhospitable sands of the Kalahari Desert. Population istherefore concentrated away from the desert in the east of the country. Life expectancy at birth is64.4 years, which is a considerable achievement given that just 10 years earlier, Batswana wereexpected to live an average of 41.4 years (UNDP, 2004; 2014). This low life expectancy was a resultof the fact that HIV/AIDS has hit Botswana particularly hard; the country has one of the world’s4

CARIAA Working Paper #7highest rates of infection, at 23% of the adult population, trailing only Swaziland and Lesotho(UNDP, 2014). Improvements in life expectancy are a testament to the country’s response strategyto the health crisis. The median age for Batswana is 22.8 years, and children are in school for anaverage of 8.8 years, four years longer than the average for sub-Saharan Africa (UNDP, 2014).Botswana’s economy is growing at a healthy rate of 5.8% per year (World Bank, 2015). Grossnational income per capita is US 14,792 (in 2011 dollars, adjusted for purchasing power parity),though it should be noted that there is a significant gap in income across gender lines: grossnational income per capita for women is US 11,491, while for men it is US 18,054 (UNDP, 2014). Interms of contribution to GDP, the economy is dominated by the mining sector, particularly theextraction of the country’s extensive diamond deposits: diamonds account for one-third of thecountry’s GDP, 70–80% of export earnings, and one-third of government revenues (CIA, 2014). Thisdependence on a single luxury export makes Botswana vulnerable to global economic downturns.The mining sector also extracts copper, nickel, potash, coal, iron ore, and silver (CIA, 2014).Other important economic sectors include tourism, financial services, subsistence farming, andcattle raising (CIA, 2014). Only 0.7% of Botswana’s land is arable, and a negligible amount isirrigated; what agriculture exists is typically rain-fed, and the country depends heavily on foodimports (MEWT, 2012). The main constraints to the agricultural sector are poor soils, inadequateeconomic infrastructure, scarce water resources, and recurrent drought (MEWT, 2012).Nevertheless, 41% of the rural population depends on subsistence agriculture for its income, with afocus on sorghum, corn, and millet (MEWT, 2012; Statistics Botswana, 2014). According to the mostrecent population and housing census, 30% of Batswana households receive their income from oneor more agricultural or livestock activities (Statistics Botswana, 2014). Livestock is a morestrategically and culturally important sector than crop production, with animals widely held for inkind income (Adaptation Learning Mechanism, 2009; MEWT, 2012).Much of Botswana’s success can be attributed to its political stability; development gains have notbeen reversed by conflict or instability, and the country has enjoyed almost five uninterrupteddecades of civilian leadership and democratic elections since independence in 1966 (CIA, 2014).The head of state is President Ian Khama, who is currently serving his second term. One area inwhich Botswana’s parliamentary democracy lags is the number of elected female parliamentarians;women take up just 7.9% of seats in Botswana’s parliament, which is well below average for subSaharan Africa (21.7%) and is among the lowest rates in the world (UNDP, 2014). Botswana islisted as clean on Transparency International (TI)’s 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index, ahead ofSpain, Portugal, and Poland (TI, 2014). Finally, the country is curr

Climate change presents a very real challenge to Botswana's continued development and relative prosperity. An increasing population and growing demand for water — from . Botswana's rich mineral resource deposits , in particular its large diamond reserves (the world's largest diamond mine is in Botswana). Botswana is less vulnerable to the

Planned and Emergency Utility Outage Guidelines Facilities Management - Planned and Emergency Utility Outage Guidelines Page 3 of 12 Issued: July 12, 2010 Revised: May 1, 2011 Revised: December 17, 2012 PLANNED OUTAGES: Planned outages shall include all repair projects with enough lead time to allow

Pentera, Inc., is the leading full-service boutique planned giving marketing communications firm, with offices in Indianapolis, Boston, and New York. Pentera was founded in 1975 by renowned planned giving pioneer and expert Andre R. Donikian, JD. Pentera's current CEO, national planned giving marketing expert Claudine A. Donikian, JD,

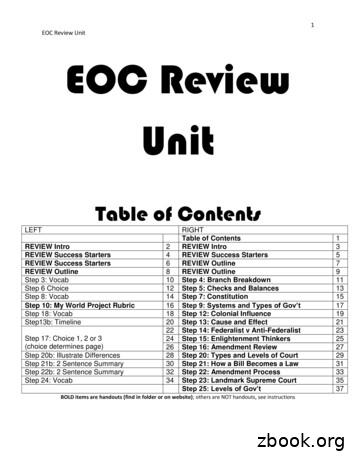

1 EOC Review Unit EOC Review Unit Table of Contents LEFT RIGHT Table of Contents 1 REVIEW Intro 2 REVIEW Intro 3 REVIEW Success Starters 4 REVIEW Success Starters 5 REVIEW Success Starters 6 REVIEW Outline 7 REVIEW Outline 8 REVIEW Outline 9 Step 3: Vocab 10 Step 4: Branch Breakdown 11 Step 6 Choice 12 Step 5: Checks and Balances 13 Step 8: Vocab 14 Step 7: Constitution 15

as in a campaign. Instead, a planned gift is usually a donation made from the assets accumulated over a person's lifetime, and it is most often a contribution to an endowment. For some donors, a planned gift is part of an overall estate plan, which they have developed with a tax, legal and/or financial professional, since planned giving tools

Article 9: La Jolla Planned District ("La Jolla Planned District" added 3-27-2007 by O-19595 N.S.; effective 4-26-2007.) . Community Resource -Community resources are visual, cultural, archaeological, architectural, and historical focal points within a community

FACT:Although Planned Parenthood health centers comprised 10% of the country's safety-net centers that offered family planning care in 2010, they served 36% of patients served by such centers. In 21 percent of counties with a Planned Parenthood health center, Planned Parenthood was the only safety-net family planning provider; and in

Table PR4: Acute Diagnosis Categories (Version 2.1 - General Population) 15 Table PR1: Procedure Categories that are Always Planned (Version 2.1 - THA/TKA Population) 20 . We based the planned readmission algorithm on three principles: 1. A few specific , limited types of care are always considered planned (obstetrical delivery, .

suffering planned giving budget decreases. That's an increase of 14% over a 30-day period. 79% Percentage of nonprofits that are moving forward with planned giving marketing Despite fundraisers' initial trepidation, donors' response to planned giving marketing has been overwhelmingly positive. 28%