System Of Health Accounts (2011) And Health Satellite Accounts (2005 .

System of Health Accounts (2011)and Health Satellite Accounts(2005): Application in Low- andMiddle-Income CountriesIntroductionAccounting data on economic and financial resource flows within the healthsystem are critical to informing health and economic policy at both nationaland international levels. Information allows stakeholders to compare spendingacross time and against internal or international benchmarks for increasedtransparency and stronger decision making on resource allocation. It is alsoan essential input in effective planning and implementation of health programs.Statistics for analyzing performance are more important than ever before ascountries around the world pursue universal health coverage reforms to expandaffordable access to health care services, without risk of financial hardship, whilefacing real resource constraints in the aftermath of the global economic crisis.For the most part, institutions that produce accounting data in the health systemrecognize the advantages of creating methodological standards that ensurecomparability over time and internationally. However, countries vary widely in theirindividual health accounting histories as well as the level of demand for and capacityto produce these data. Additionally, stakeholders within countries have differentperspectives on the health system and thus have different specific data needs.Consequently, there has been some divergence in the approaches that countriesaround the world have taken to satisfying country-level health accounting needs.As the production and use of health accounting data continue to spread, countriesneed to understand how the approaches – their methods and data applications– fit their context and policy needs. Health stakeholders, including data usersand technical experts as well as data producers, should be informed about thecharacteristics common to all approaches as well as the relative value of each inanswering policy relevant questions.The purpose of this brief is to introduce non-technical policymakers and otherstakeholders to two prominent health accounting approaches: the System of HealthAccounts (SHA), developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation andDevelopment (OECD) and its partners, and the Health Satellite Accounts (HSA)developed by the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for the Americas(AMRO). The approaches are closely related to and must be understood in relationInsideIntroduction.1Background on Health Accounting.2Summary Comparison of theApproaches.4Conclusions.9Annex A. List of SHAand HSA Classifications andAccounts.10Annex B. Policy Applications.13References.16This brief was authored bySharon Nakhimovsky, Senior Analyst,Health Finance and Governanceproject; Patricia Hernandez-Peña,Researcher, Netherlands InterdisciplinaryDemographic Institute; Cornelius vanMosseveld, Health Economist, WorldHealth Organization; Alain Palacios ,Researcher and Health Accountant,Department of Health Economics,Ministry of Health, Chile for the HealthFinance and Governance project.

2to the System of National Accounts (“NationalAccounts”), the international framework foranalyzing economic information in a country.The SHA focuses on the health care goods andservices consumed by a country’s populationand illustrates the flows of resources used topurchase them, beginning with their financingorigins. The HSA focuses on the productionof those health care goods and services andreplicates the content of the National Accountsfor the health field, including the value added ofhealth care service production and the interactionof health resource flows with the rest of theeconomy.This brief compares the SHA and HSAapproaches to health accounting in terms oftheir objectives and content, standardization andscope, and data requirements. The purpose of thiscomparison is to communicate the main policyapplications of the data each approach producesas well as the primary factors determiningfeasibility and data quality. The comparison isby no means exhaustive. Rather, it is intendedto start a discussion to which non-experts cancontribute and from which they can gain furtherunderstanding.Background on HealthAccountingNational and health accounting have developedsignificantly in the last half century. Building onwork to increase international cooperation in theyears following the Great Depression and WorldWar II, upper-income countries experimentedwith health accounting while building internationalframeworks for national accounting. Momentumgrew in the 1970s and 1980s, with effortsculminating in the adoption of the third generationof the National Accounts in 1993 by the UnitedNations, International Monetary Fund, WorldBank, and others (Inter-Secretariat WorkingGroup on National Accounts 1993). This versionwas the first to provide guidelines1 for producingsector-specific “satellite accounts,” intended tocomplement the central framework so that itwould not be overburdened with sector-specificpolicy information. Examples of satellite accountsinclude those for health, tourism, culture, oil,environment, and education.In 2000, with accumulating experience in healthaccounting and growing interest in healthsystems, the OECD in collaboration with theEuropean Statistical Office proposed a differenttype of health accounting satellite. SHA 1.0(OECD 2000) was intended to provide countrieswith a standardized approach to and detailedclassifications for describing the health system.2It was based on methods applied in NationalAccounts, but departed in key ways in order tosatisfy characteristics of the health sector thatdiffer from other sectors of an economy. Mostnotably, the data in the SHA are structured toemphasize the flow of resources from origin toend use in a way that is relevant for health systemspolicymakers.In 2003, the World Health Organization, WorldBank, and United States Agency for InternationalDevelopment (USAID) published the Guideto producing national health accounts. This“Producer’s Guide” adapted the SHA approachSee National Accounts 1993 chapter XXI for these guidelines.In particular, the Harvard School of Public Health was active inpromoting health accounting, which they called National HealthAccounts, in a way that was then standardized with the publicationof SHA 1.0 in 2000 and the Producer’s Guide in 2003.12

System of Health Accounts (2011) and Health Satellite Accounts (2005): Application in Low- and Middle-Income Countriesto the developing-country context – a “how to”version of SHA called National Health Accounts(NHA) that increased the approach’s utility andstandardization in low-income and middle-incomecountries.At the same time, AMRO was developing anotherversion of a National Accounts health sectorsatellite. Like SHA 1.0, the HSA differs from theNational Accounts in key ways to reflect healthspecific realities, but unlike SHA 1.0, it does notsignificantly diverge from the data structure ofthe National Accounts; the HSA complementsthe National Accounts, by replicating the latterapproach for the health branch to provide moredetails on the use of health care by the country’spopulation. Several countries (e.g. France, theNetherlands, and the United States) had usedthis type of approach to health accounting evenbefore the satellite approach to sector-specificaccounting was proposed in 1993. Building off thisexperience, in 2005, the Satellite Health AccountManual (Pan American Health Organization 2005)standardized the concepts and definitions used inthe HSA. Figure 1 displays the timeline nationaland health accounting development since thepublication of the 1993 National Accounts.Further developments in health accountinghave taken place throughout the past decade.In response to issues identified by practitionersof the aforementioned approaches and totrends in economies, health systems, andaccounting methods, leaders in both nationaland health accounting updated the internationalmethodological standards in National Accounts2008 (Inter-Secretariat Working Group onNational Accounts 2009) and SHA 2011 (OECDet al. 2011). AMRO is currently updating itssatellite to reflect the National Accounts2008 framework. Other approaches to healthaccounting have emerged as well, includingUNAIDS’ National AIDS Spending Assessment(NASA), the World Bank’s Public ExpenditureReview (PER), and the Clinton Health AccessInitiative’s (CHAI) Resource Mapping Tool.Figure 1. Timeline of Development of National and Health Accounting ApproachesSource: Authors3

4Summary Comparison ofthe ApproachesPurpose and ContentBecause both the SHA and HSA analyze pasttrends in health spending in order to informa country’s policy making, there is substantialoverlap in their objectives and in the informationthey capture. However, this fact hides realdifferences in the focus and content of theapproaches. SHA: The primary objective of the SHA isto guide health systems policy making, andespecially to enable allocation of healthresources in close alignment with health systemstrategies and objectives. To this end, the SHAorganizes data in a way that documents theflow of funding, from origin to destination,for the health care goods and services thatare consumed by a country’s residents.Documentation of this flow allows the SHA tofocus on the interaction between the user andthe health system as well as distribute healthexpenditure in various, policy-relevant ways.3 Itsmain purposes are to inform decision makingin the health system, including budgetingand strategic planning, and to propose aninternationally comparative framework forhealth expenditure data. HSA: The primary objective of the HSA isto inform public policies and decision makingon programs and projects related to thehealth sector and link the health branch tomacroeconomic growth and developmentin the economy.4 To do this, the HSA appliesthe structure of the 1993 National Accountsframework, with its macroeconomic focus,to health information. By examining theDistributions of current health spending relate to aspects suchas providers, factors of provision, and different aspects of thepopulation, such as demographic, socioeconomic, geographicallocation, and disease supplemented by a classification for capitalgoods.4To a large extent, the HSA does macro and meso analysis, whichmeans that it has a broader scope – including that of the SHAbut going beyond it. These aims serve policymakers primarilyin macroeconomic areas (and who are familiar with NationalAccounts indicators) and in the health system.3production of health care goods and servicesand documenting the health care goods andservices that the country’s residents consume,the HSA provides selected information onthe interaction between the health sector andthe rest of the economy. This informs healthsector planning and broadens policymakers’understanding of the contribution of the healthsystem to national development.While the two approaches collect and analyzesimilar information, their different foci mean thatthey handle information differently. Specifically,they organize information about the financing,production, and use of health goods and servicesdifferently and in varying levels of detail. Financing of services: One objective ofthe SHA is to describe the complex financialarrangements and interactions between variousactors in a country’s health system. The SHAuses a series of classifications to show howresources are collected and then managedand allocated to providers through “financingschemes” for the goods and services used byindividual households or larger populationgroups. For example, one flow may show atransfer of funds from the Ministry of Financeto the Ministry of Health which then, throughgovernment programs, purchases the inpatientcare of urban residents at public hospitals.5Tracking these flows of resources can informpolicy analysis and the planning and budgetingprocess.The HSA communicates health financinginformation differently6,7. The main table forthis information in the HSA is the Financing ofNational Health Expenditure, which, unlike theSHA, does not distinguish between the ultimatesources of health funds and the managementof those funds. The HSA does contain the5The flow described in this section could also be broken down inother ways (e.g. by factors of provision or disease) using the SHA toprovide additional policy-relevant information.6In the SHA, financing is crucial and a main axis in reporting tables.In the HSA, financing is not prioritized as in the SHA.7For non-market producers, financing in the HSA correspondsto social contributions and transfers. In most cases, the financingmechanisms of insurers (e.g. social contributions or premiums andcost-sharing) can be clearly identified for the HSA. However, this isnot the case with all providers, the financing for which then needsto be derived from the Supply and Use Tables in National Accounts.

System of Health Accounts (2011) and Health Satellite Accounts (2005): Application in Low- and Middle-Income Countriesinformation on the flow of financing for healthgoods and services that a country’s residentsconsume, but additional data must be pulledfrom other tables and accounts to completethe picture. The SHA ultimately gives a moredetailed presentation of the financing flowsthat deliver the health care goods and servicesconsumed – important in an era when healthfinancing systems are becoming more andmore complex.SHA also compiles the value of inputs likepharmaceuticals for patient care. However, theSHA remains focused on the health system – itdoes not further break down the productionof those pharmaceuticals, or other inputs tocare.10 Use of health care: In addition to healthfinancing, the SHA also focuses on compilingand analyzing the types of goods and servicesused by the population and the groups withinthe population who benefit from them.These groups may be defined according todemographic, geographic, socio-economic, andepidemiological characteristics. For example,given sufficient data, the SHA can provideinformation on how much spending went towomen as opposed to men, to rural groups asopposed to urban ones, to low-income groupsas opposed to high-income groups, and toHIV/AIDS as opposed to non-communicablediseases. The HSA also conducts this type ofanalysis, but not in the same degree of detail asthe SHA.11 Production of health care goods andservices: The HSA provides extensiveinformation on the flow of inputs8 used toproduce the health care goods and servicesthat are consumed at home or abroad, orinvested to benefit the country’s economicproductivity over many years. The HSAcompiles information on the inputs used by theproducers of health care goods and services(within the health sector), as well as at leastsome of the entities involved in the productionof those inputs (not necessarily within thehealth sector). For example, pharmaceuticalsare an input to patient care delivered ata health facility; their production involvesother inputs: the labor of chemical engineers,electricity, and so forth. The analysis of theproduction process includes estimating thevalue added – that is, the difference betweenthe total value of all the goods produced,including those that are exported to othercountries, and the total value of the inputs usedto make them.9 This detailed breakdown ofinformation links the health sector to the restof the economy, which can inform economywide planning for national development. TheHSA contributes this additional information onhealth care production, which links the healthbranch to the rest of the economy (or at leastselected components).Like the HSA, the SHA analyzes the inputsused to produce health care goods andservices. To continue the example above, the“Inputs” are goods and services that are used up in the processof producing other goods and services.9This is true except when prices are not available for the goodsand services. In that case, analysts use data on the cost of inputs toestimate the production, with the assumption that the productionis equal to the sum of inputs.8To summarize, both the SHA and HSA arepolicy tools that support the health system bydocumenting health spending, but differ in theirapproach and areas of focus. These differencesmanifest in differences in data structure as well aspolicy application. See Annex A for more detailon the classifications and accounts that make upthe two approaches and Annex B for more detailon their policy application.Standardization and ScopeThis section compares the standardization andIn addition to the analysis of inputs to production described inthis section, the SHA and HSA both analyze the providers usedto deliver goods and services. The two approaches use a similarclassification, but the SHA’s provider classification is more detailedand allows for a subtle analysis of the structure of their healthsystem.11The analysis of consumption in the HSA links the goods andservices produced to their consumption by institutional sectors(households, government, corporations, including insurance, nonprofit institutions serving households, and foreign institutions). Thisanalysis in the HSA also links the goods and services to variousagents which finance them. Some agents, notably the government,purchase services on behalf of households, who ultimately benefitfrom those services along with those purchased directly orthrough other means.105

6scope of the SHA and HSA approaches in thecontext of other national and health accountingapproaches. For this discussion, “standardization”refers to the level of alignment between themethods, definitions, and boundaries of theapproach – which must be clearly defined –and those of the National Accounts. As wasdiscussed earlier, the National Accounts is theinternational standard for analyzing economicinformation in a country, and is comprehensivein its representation of all activities and actorswithin and between sectors of the economy.Standardization allows for consistent applicationacross countries and over time. The NationalAccounts produces critical macroeconomicindicators such as gross domestic product (GDP),which, when combined with well-aligned healthaccounting data, can produce other importantmacro indicators such as health spending as apercentage of GDP. Alignment with NationalAccounts thus implies additional analytical poweras well as international standardization.The “scope” of the approaches is the degree towhich the approach tracks public and/or privatespending and the areas or sub-areas (such as HIV)of the health system being studied. Tracking bothpublic and private sectors is necessary for a truepicture of a country’s health spending becauseprivate health spending represents a substantialamount, if not the majority, of health spending inmany countries. In particular, household outof-pocket spending is often a large componentof private spending in low- and middle-incomecountries, and it is becoming the target of effortsto improve financial protection and equityin access; hence, it is an important indicatorto track. Moreover, understanding privatespending in relation to total spending on healthis essential for stakeholders inside and outsidethe government interested in comprehensive,evidence-based planning for the health sector. Asfor whether health or one of its sub-areas, suchas HIV, is covered, all approaches have analyticaladvantages for their target audiences.One notable commonality for the SHA and theHSA approaches is that they are both explicitlyaligned with the National Accounts in theircapacity as satellites. As also discussed earlier,sub-analyses of the National Accounts detailthe economic and financial resource flows ina priority sector such as education, health, ortourism without overburdening the NationalAccounts’ central framework. National Accountssatellites can adjust the National Accounts’accounting principles and estimation methods inorder to accommodate the economic and financialprofile of the particular sector, and generate theinformation stakeholders need, while maintaininglinkages with the central framework. In thisway, National Accounts satellites for the healthsector can address health policy needs whileensuring alignment with National Accounts. Bothapproaches make these changes, detailing them instatistical manuals that substantiate their overallrelationship with the National Accounts and allowfor consistent international application.While standardization is important, it is alsoworth noting that the SHA and the HSA, as wellas the National Accounts, allow for adaptingthe approach to the country context in termsof country-specific policy needs and statisticalsystem capacity. For example, the NationalAccounts encourages countries to completethe core analysis, and then to select additionalcomponents that are most relevant and feasiblefor them to complete. The SHA and the HSAalso are explicitly open to countries applying theapproaches in a flexible way. This flexibility isreflected in reports that display different levels ofaggregation and grouping of the data. That beingsaid, the closer country data adhere to the SHAstandard, the more meaningful are comparisonsacross countries and time.In fact, the SHA and HSA are the only two widelyused approaches that are both aligned with theNational Accounts and cover both public andprivate spending on health as well as the healthsector as a whole. Table 1 shows several otherprominent health accounting methodologies usedin the health sector and their standardizationand scope dimensions. While the list is notcomprehensive, it represents the most widelydiscussed and used health accounting approachesglobally.UNAIDS’ NASA, for example, is also based onthe National Accounts and covers both public andprivate spending, but like the Expenditure Analysis

System of Health Accounts (2011) and Health Satellite Accounts (2005): Application in Low- and Middle-Income CountriesTable 1. Scope of the SHA and HSA Compared to Other Prominent Health Accounting ApproachesNational Accountsbased?All Sectors Covered?All Health AreasCovered?SHAYesYesYesHSAYesYesYesNASAYesYesNo, HIV onlyExpenditure AnalysisNoYesNo, HIV onlyPERNoNo,public sector onlyYesResource Mapping ToolNoYesYesApproachconducted by the President’s Emergency Plan ForAIDS Relief, only covers HIV spending. The WorldBank’s PER covers all health areas, but is not basedon the National Accounts and covers only publicexpenditure. Finally, the CHAI Resource MappingTool covers public and private spending on healthas well as all health areas, but is not based on theNational Accounts.The SHA and HSA have both been used by a widerange of countries. The SHA has wider usage,both geographically and by country income level– France (GDP per capita of US 39,772 in 2012),Democratic Republic of Congo (GDP per capitaof US 262)12 , and more than 100 other countriesin Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas usethe approach. Also, the latest version of SHAwas developed through a consensual processled by OECD, EUROSTAT, and WHO in whichhealth accountants representing all regions inthe world agreed on what and how to measurehealth expenditure, and in this way is consideredby many to be the international standard forhealth accounting. To date, the HSA has beenused primarily in the Latin America and Caribbeanregion. However, interest in it has sparkedrecently in other parts of the world such as China,which conducted its own version of the HSA.While the SHA and HSA are both closely alignedwith the National Accounts, they differ in thatonly the HSA is a full satellite that contains all12Income per capita data come from the World Bank 2014.components of the National Accounts, i.e.,including a description of the production of healthcare goods and services and the value added thatit generates. The SHA is not a full satellite, but itdoes contain additional components – notably toanalyze the use of health care – which allows it tofocus on generating policy-relevant informationfor health system professionals to a greater extentthan the HSA.13Data RequirementsGiven the similar scope, the two approaches usemany of the same types of data. The discussionbelow describes some of the primary data sourcesand data collection methods used to informestimates for the two approaches.Public Sector: Both approaches requireexecuted budgets as well as administrative recordson assets and capital formation from governmentagencies, of all levels, that spend on health.Even though the HSA is closely aligned with the NationalAccounts, its indicators do not have extensive applicability to healthsystem policy making. While the SHA is partially aligned with theNational Accounts, its indicators are more usable in health systempolicy making.137

8The quality of public sector estimates, in bothapproaches, depends on the organization anddetail of these budgets and records. When theorganization and detail of the sources do notalign with the classifications of the approaches,the health accounting team needs to makeassumptions in order to complete the estimations,thus reducing the power and accuracy of theestimations. As countries make health accountinga routine part of governmental operations,accounting teams can work with budgeting andaccounts teams to improve the compatibility ofpublic sector sources with the approaches, thusimproving the quality of the estimations andultimately advancing health systems governancestructures. Because both approaches are linkedwith National Accounts, improving compatibilitywith one approach will likely also improvecompatibility with the other, though some specificaspects may vary.Private Sector: Private expenditure datarequired for both approaches come frominstitutions – donors, non-governmentalorganizations (NGOs), insurance companies, andemployers, as well as private providers – and fromhouseholds. The more data are available throughroutine systems (survey and information systemdata), the less ad hoc primary data collection isnecessary for health accounting. Moreover, itis likely, with routine systems, that the healthaccounting estimates will be of better quality andmore routinely completed. Countries vary in theamount of applicable routine systems and surveydata available. The challenge in many low- andmiddle-income countries is that these availabledata are often insufficient to complete theestimation for the approaches.In response to this challenge, application of theSHA in low- and middle-income countries typicallyinvolves appreciable primary data collection togather both institutional and household data onprivate health expenditure. Private institutionaldata are gathered from financiers such as donors,NGOs, employers, and insurance companies.HSA estimations conducted in data-poor settingswill sometimes use SHA-like methods for thecollection of these data, within the context ofapplying national accounting methods to the healthsector.14Methods for gathering information on householdspending – often the largest component of privatehealth expenditure – will vary with the type ofavailable data. Best practice for estimating privatehousehold spending with the SHA, based on datafrom upper middle- and high-income countries,involves identifying challenges for estimating eacharea of spending (e.g., spending at hospitals and onpharmaceuticals) and developing a measurementstrategy to tackle them one by one through theintegration of data from different sources (e.g.,providers, financiers, and households) (RannanEliya and Lorenzoni 2010).15In some low- and middle-income countries,however, identifying even one of these datasources can be a resource-intensive exercise.In these cases, SHA estimation may involveconducting nationally representative householdsurveys to gather households’ health expenditureinformation. These data may also be collectedby integrating a module on health expenditureinto other household surveys. In other cases,routine household budget surveys can be used tocomplete these estimations. Still, all householdsurveys of health expenditures have intrinsicmeasurement challenges that may make it difficultto estimate accurately.16 Thus, when rigorouscentral National Accounts data are available,whereby household budget survey data have beencross-checked in a sophisticated way, the SHA aswell as the HSA will use those data to inform theestimates of household spending.Because of its basis in national accounting methods, the HSArequires the skills of national accountants, and in several LatinAmerican countries (e.g., Brazil, Ecuador, and Mexico) the HSA isdeveloped by National Statistical Institutes that also produce theNational Accounts. The highly technical nomenclature used in theHSA also contributes to this need for developed skills in nationalaccounting.15This process involves the “triangulation,” or cross-checking andvalidation, of data from different sources (both supply and demand).16In addition to measurement challenges, the high cost of welldeveloped household surveys in low-income countries and thefact that they are conducted infrequently are the primary driver ofinstitutionalization of health accounting.14

System of Health Accounts (2011) and Health Satellite Accounts (2005): Application in Low- and Middle-Income CountriesIn addition to institutional and householdexpenditure data, completing the HSA also requiresgathering data on the production of health caregoods and services in the private sector. HSAestimates on private production in the health sectorcan be based on the central National Accounts,especially the Supply and Use Table (see AnnexA for more information), as well as businesssurveys that are conducted regularly and includehealth sector businesses in their sample. In somecountries, however, National Accounts systems arenot up to date, or do not include a rigorous Supplyand

of SHA 1.0 in 2000 and the Producer's Guide in 2003. . and Health Satellite Accounts (2005): Application in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 3 to the developing-country context - a "how to" version of SHA called National Health Accounts (NHA) that increased the approach's utility and . methodological standards in National Accounts .

chart of accounts from a legacy system. You first need to create a new company database with a user-defined chart of accounts. You can also use DTW to add accounts to an existing chart of accounts, including a chart of accounts based on the default localization template. Use

Accounts receivable 100 Sales 100 Accounts Receivable Allowance for Doubtful Accounts Beg. 500 25 Beg. End. 600 25 End. Sale 100 Slide 7-22 UCSB, Anderson Accounting for A/R and Bad Debts Collected of 333 on account ? Cash 333 Accounts receivable 333 Accounts Receivable Allowance for Doubtful Accounts Beg. 500 25 Beg. End.

Accounts Branch Sh. Ajay Bartwal JDFCCA (Accounts Dte) Room No. 417 Rly. No. (030) 47018 P&T (011) 23047044 ajay.bartwal@gmail.com 2 ACCOUNTS Sh. Sudhir Kumar Pay & Accounts Officer Room No. 21, Ground Floor Rly. No. (030) 43655, 45301 P&T (011)23388674 sudhir.kumar1708@gov.in Accounts Branch Sh. Ajay Bartwal JDFCCA (Accounts Dte)

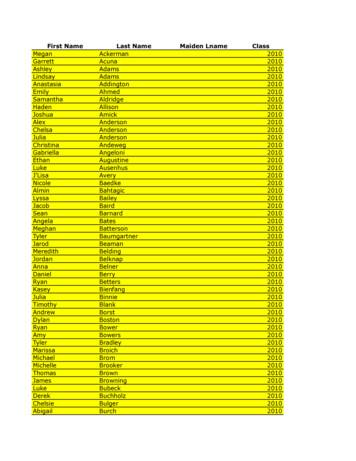

Ashley Harris 2010 Blake Hartsook 2010 Denira Hasanovic 2010 Ella Heinicke 2010 Amber Heller 2010 . Ryan Coulson 2011 Dellanie Couture 2011 Emily Coy 2011 Allison Crist 2011 Kerrigan Crotts 2011 . Alexandra Hawks 2011 Trevor Heglin 2011 Marisa Heisterkamp 2011 Brett Heitkamp 2011 Caleb Helscher 2011

Because every business transaction affects at least two accounts, our accounting system is known as a double-entry system. (You can refer to the company's chart of accounts to select the proper accounts. Accounts may be added to the chart of accounts when an appropriate account cannot be found.)

1. Creating H.O.D accounts 2. Can reset the password of the H.O.D accounts in-case it is forgotten. Actions to be performed by the “H.O.D Accounts” After creating the H.O.D accounts by the principal of the college, the credentials will be securely communicated by the

Context Business financial accounts and national accounts have been harmonized and aligned in order for business accounts to feed into the statistical production process of the System of National Accounts. With more and more businesses beginning to undertake sustainability accounting and reporting, there is now an opportunity to align business sustainability accounts, as they pertain to .

Tourism and Hospitality Terms published in 1996 according to which Cultural tourism: General term referring to leisure trav el motivated by one or more aspects of the culture of a particular area. ('Dictionary of Travel, Tour ism and Hospitality Terms', 1996). One of the most diverse and specific definitions from the 1990s is provided by ICOMOS (International Scientific Committee on Cultural .