By Geoffrey Cowan And David Westphal - Nieman Lab

Center on Communication Leadership & PolicyResearch Series: January 2010Public Policy and Funding the Newsby Geoffrey Cowan and David Westphal 2010 University of Southern California

Geoffrey CowanDavid WestphalAbout the AuthorsGeoffrey Cowan, director of the Center on Communication Leadership & Policy, dean emeritus of theUSC Annenberg School and USC University Professor, holds the Annenberg Family Chair inCommunication Leadership. Cowan served under President Clinton as the director of the Voice ofAmerica and director of the International Broadcasting Bureau. In other public service roles, he servedon the board of the Corporation of Public Broadcasting, chaired the Los Angeles commission thatdrafted the city’s ethics and campaign finance law, and chaired the California Bipartisan Commissionon Internet Political Practices.Cowan is the Walter Lippmann Fellow of the American Academy of Political and Social Scienceand an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He chairs the CaliforniaHealthcare Foundation board of directors and serves on the Human Rights Watch board, where he cochairs the communication committee. He previously was a fellow of the Shorenstein Center on thePress, Politics, and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. A graduate of HarvardCollege and Yale Law School, Cowan is an award-winning author, playwright and television producer.David Westphal, senior fellow with the Center on Communication Leadership & Policy, is executivein residence at the USC Annenberg School. Until joining USC in fall 2008 he was Washington editorof McClatchy Newspapers, the nation’s third largest newspaper company. Westphal joined McClatchyin 1995 as deputy bureau chief and was named bureau chief in 1998. With McClatchy’s purchase ofKnight Ridder in 2006, he became editor of the combined Washington bureaus and the McClatchyTribune News Service. Previously, he was managing editor of The Des Moines Register in Iowa for almostseven years. His newspaper career spanned nearly four decades.This project is made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York.The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Public Policy and Funding the NewsIntroductionby Geoffrey CowanAt a time when the financial model for newsis facing the greatest crisis in decades,the level of government funding for news organizations has been declining sharply. Unless a newapproach is created, that decline is likely toaccelerate. Yet most commentators, includingmembers of the press, seem unaware of the levelof government support that journalism hasenjoyed throughout our nation’s history, or of theways in which it is now disappearing. This reportbegins the process of documenting the cutbacksand presenting a possible policy framework forthe future.The sharpest cuts have come in the level ofpostal subsidies for news which have beenreduced by more than 80 percent over the lastfour decades. Thanks to the visionary leadershipof George Washington and James Madison,mailing costs were heavily subsidized by thegovernment for the first 180 years of our nation’shistory – from the Postal Act of 1792 to thePostal Reorganization Act of 1970. In 1970, thePostal Service subsidized 75 percent of the cost ofperiodical mailings. Today, the subsidy has fallento just 11 percent. In today’s dollars, that’s adecline from nearly 2 billion in 1970 to 288million today. Magazines that would still beprofitable under the arrangement established byour founders are now closing at a precipitous rate.Public and legal notices have also been animportant source of revenue for the publishingindustry throughout American history. Thanks tolegislation and regulations adopted at every levelof government, they remain a huge source ofrevenue today. They provide hundreds of millionsof dollars to periodicals ranging from local dailyand weekly papers to national publications such1as The Wall Street Journal. But inevitably they willbe reduced and eliminated, superseded byadvances in new technology. Cash-strappedgovernment agencies are asking courts andlegislative bodies to allow them to make theswitch to the Internet. Legislation to allow atransition to the Internet has been introduced inat least 40 states, and in some the switch to theWeb is under way. Arizona school districts, forexample, are now free to publish their yearlybudgets on their own Web sites, avoiding costlyplacement in local newspapers. PresidentObama’s Department of Justice recently proposeda similar transition. While lobbyists and lawyersfor some media companies are trying to blockthese changes, a day of reckoning is clearly on thehorizon. The loss in revenue will be substantial.Print publications of all kinds also benefitfrom a wide range of tax breaks that have beenspecifically designed to help news outlets. Thereare special tax provisions in the federal tax codeand in most states. Collectively, they account forhundreds of millions in lost tax revenues. Forexample, the federal tax code has provisions forthe special treatment of publishers’ circulationexpenditures as well as special rules for magazinereturns. Those two sections of the code accountfor a loss of 150 million in taxes – or a subsidy of 150 million for the industry. Tax breaks at thestate level, including favorable treatment ofnewsprint and ink, amount to at least 750million. The actual amount is probably muchhigher because many states don’t report separatedata for publishers. How long thosepreferences will persist is anyone’s guess.In a variety of ways, the government has alsohelped to assure the financial stability of broadcasting, cable and the Internet. Broadcasters weregiven their licenses for free; part of the trade-offfor a free license, however, was the explicitrequirement that the station use some of its

2Public Policy and Funding the Newsresources to provide news and information to theaudiences it served. Cable news channels are thedirect beneficiaries of FCC rules that allow cableoperators to bundle services, requiring every cablesubscriber to pay a fee to MSNBC, CNN and FoxNews – whether they want them or not. Thosesubscriber fees are more important than advertisements in funding the bottom line of all threecable news outlets. Until recently, none of theover-the-air broadcasters (including publicbroadcasting stations) received a single dollarfrom cable subscriber revenue. If the FCC hadfollowed the suggestion of former ChairmanKevin Martin, it would have adopted so-called ala carte cable rules that would have allowed eachcable subscriber to decide whether to pay for Foxor for MSNBC or for CNN. That change wouldhave had a dramatic impact on the businessmodel for cable news. As news migrates to broadband, it seems inevitable that the business modelfor those news outlets – and the assured stream ofsubscriber revenue – will change.Internet entrepreneurs have benefited fromthe huge federal investment in creating theInternet, and are about to benefit from billions inthe stimulus package that will be spent on broadband. By extending high-speed Internet to consumers who do not yet have it, the governmentwill be helping consumers migrate online at theexpense of conventional print and broadcast outlets. In addition, new media entrepreneurs,including many bloggers and news providers,benefit from the Internet Tax Moratorium, afederal law that, according to some estimates,reduces taxes by 3 billion a year.1 At some point,it seems likely that Congress will decide to tax theInternet.There are scores of other ways in which thegovernment helps to support the gathering anddissemination of news. The best-known forms ofsupport are the financing of public broadcastingCable news channels are thedirect beneficiaries of FCC rulesthat allow cable operators tobundle services, requiring everycable subscriber to pay a fee toMSNBC, CNN and Fox News– whether they want them or not.in the United States and of the Voice of America,Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and otheroutlets for audiences abroad. According to theCorporation for Public Broadcasting, about 1.14billion of the 2.85 billion spent on publicbroadcasting (or about 40 percent of the totalfunding for public broadcasting) comes from federal and state government sources. Much of thefunding for the major PBS news programs – the“NewsHour” and “Frontline” – comes from thegovernment, through the Corporation for PublicBroadcasting. The Corporation for PublicBroadcasting also provides special funds forprograms on urgent and controversial topics, suchas NPR’s coverage of the Iraq war.Some who read this report will feel that thegovernment does too much to support news andthat it should start at once to end those forms ofsupport that already exist. That group mayinclude people who are concerned about federaland state deficits, those who think the newsmedia is biased, and those who think that as amatter of principle and practice there should be afirm wall between the government and the newsmedia, much as there is a wall between churchand state.

Public Policy and Funding the NewsWhile the authors of this report respect thesepoints of view, we have a different perspective.We think the press is vital to democracy.Washington and Madison were right when theyinsisted that the government fund a robust postalsystem, partly to deliver news to the nation’s farflung population, and they were right tocreate postal subsidies to assure that the publicwas informed. The authors of the FirstAmendment were right when they created adocument that banned any law “respecting”freedom of religion, but only banned laws that“abridge” freedom of the press. The foundersbelieved in laws that would enhance the press,including those providing for postal subsidies,public notices and other devices that would helpto ensure financial stability. The authors of theFederal Communications Act and the earlymembers of the FCC were right to require thatstations provide news and public affairs coveragein return for receiving a federal license to broadcast. Those who wrote the Public BroadcastingAct were correct when they found a way to fundpublic broadcasting, and the credibility of government-funded news on public radio and publictelevision stands as a testament to their wisdom.We live in an era of profound technologicalchange that threatens many forms of news media.We do not favor government policies that keepdying media alive. But we do believe thatduring this transition period, government shouldexplore new and enhanced ways to support theproduction of news and information, as it hasthroughout our nation’s history.When possible, we also think that:1. The government should find ways tomake sure that reporters, news organizations andother content creators are compensated for workthat might otherwise be stolen (which is onereason why the founders provided for copyrightlaws in the Constitution).3Government should explorenew and enhanced ways tosupport the production of newsand information, as it hasthroughout our nation’s history.2. Most government funding should beindirect, rather than direct (as it is through theCorporation for Public Broadcasting and throughparticipating public radio and television stations).3. Where possible it should be distributedaccording to a formula rather than as a directsubsidy for particular news outlets (as is the casewith tax breaks and postal subsidies).4. The government can play an importantrole by investing in technology and otherinnovations, as it did when it supported researchon transistors, on satellite technology, and on theInternet.Above all, we urge an honest debate thatrecognizes the vital role that the governmenthas played throughout our history and that itcontinues to play today. It would be a publictragedy to wake up one day and discover thatnews outlets are in even deeper trouble becausebillions of dollars of public support haddisappeared while no one was watching.

4Public Policy and Funding the NewsSome public agencies which have provideddirect or indirect support to news organizations

Public Policy and Funding the News5Research Findingsby David WestphalNews Media in CrisisMost people did not see the tidal wavecoming. In June 2006 McClatchypurchased Knight Ridder for 4.5 billion plus 2 billion in debt.2 It promptly sold off some ofKnight-Ridder’s biggest papers (Philadelphia,San Jose, St. Paul and Akron) to investors whoalso didn’t see it coming. The following year SamZell took his own ill-fated leap, acquiring TribuneCo. in a 13 billion deal financed almost entirelyby borrowed money. It would take only 12months for Zell to take Tribune into Chapter 11bankruptcy court.3 The hometown owners of thePhiladelphia Inquirer would make the same choicenot quite three months later.4 About the sametime a private equity firm, Avista CapitalPartners, which purchased the Minneapolis StarTribune from McClatchy, took that newspaperinto Chapter 11. (It emerged from bankruptcycourt eight months later.)5The speed with which these blockbusterdeals came back to haunt their buyers suggeststhe nightmarish conditions that have swampedthe newspaper industry in the last few years, andwreaked havoc as well at many magazines andbroadcast outlets. More than 100 newspapersshut down in 2009.6 Most were small, but somebig newspapers shuttered as well, including theRocky Mountain News and the Seattle PostIntelligencer. The casualty list is almost certain togrow.News businesses have always been susceptibleto the ups and downs of the economic cycle, sothe violent downturn of 2008 and 2009 wascertain to knock them for a loop. But that wasonly part of what was sending their stock prices,Bad times for ad revenuesNewspaper advertising revenue is in afree fall, down 27 percent between 2005and 2008—and the results from the firstnine months of 2009 are even worse.2005: 46.7 billion2006: 46.6 billion2007: 42.2 billion2008: 34.7 billion2009: 17.9 billion (thru 9/30)Source: Newspaper Association of Americarevenues and earnings into a tailspin. All legacymedia were buffeted by the rapid advance ofWeb-based and other digital technology thatincreasingly pulled consumers from traditionalmedia. In the case of newspapers, the Web’simpact was particularly brutal because it robbedthem of most of their classified ads, which by farwere their most profitable form of revenue. JeffreyKlein, a former top executive at the Los AngelesTimes, has said that in some years classified adsprovided all of the Times’ profit margin.These are among the numbers that haverocked the news business and eliminated tens ofthousands of jobs:

6Public Policy and Funding the News Newspaper advertising revenue, down 9.4percent in 2007, dropped a dramatic 17.7 percentin 2008. The picture grew even worse in 2009,with ad revenue down 28 percent through thefirst three quarters.7 The decline of newspaper circulation alsoaccelerated, with the number of subscribersfalling below pre-World War II totals, when thecountry’s population was half that of today’s.8 Audiences for network evening news showsalso continued to slide, even in a robust presidentialelection year. The broadcast networks averaged 23million viewers in 2008. Less than two decadesearlier, the networks had double that audience,even with an overall population that was 20percent smaller.9 The major weekly news magazines alsoexperienced falling circulation, though not at thesteep levels of many newspapers. Newsweek wasdown 25 percent, and Time was off 18 percent,between 2002 and 2009. U.S. News & WorldReport discontinued weekly publication and shiftedits traditional news operations to the Web.10Economic recessions have often resulted innewsroom staff reductions, but this one took agigantic toll. Editors made round after round ofnewsroom cuts. Many who survived enduredwage freezes, or cuts, or mandatory furloughs, orall of the above. Vacations were reduced. Pensionswere eliminated; company matches on 401(k)plans were terminated. According to the Web sitePaper Cuts, newspapers eliminated nearly 15,000jobs in 2009.11 Not atypical was the experience ofthe Los Angeles Times, whose newsroom in 2009was less than half its size a decade earlier.Most publications also drastically reducednews pages. Editors trimmed stock listings andTV books years ago, but now they were forced toreduce or eliminate many of their prizedsections – books, arts, business, local news. Mostalso took a mighty whack at state, national andIt is possible to imagine a futurenews ecology that will be much,much richer than the one we areleaving behind. Yet it is unclearwhether that vision will reallyemerge, or if it does, how long itwill take to happen.foreign bureaus. Newhouse, Copley, MediaGeneral and Cox all shut down their Washingtonbureaus.12 Cox closed its foreign bureaus as well.Virtually every news organization that maintained a state capital presence pulled back.Statehouses like those in Denver and DesMoines, which once housed 25 to 35 reporterseach, were down to five or six.If this were the end of the story, some sort ofemergency federal response might be in order.But it is not. New news sources are emerging at arapid pace, from local community news sites toFacebook news groups to national investigativenonprofits. It is possible to imagine a future newsecology that will be much, much richer than theone we are leaving behind. Yet it is unclearwhether that vision will really emerge, or if itdoes, how long it will take to happen. In the shortrun, as news resources in legacy media continue toshrink, there are questions about Americans’ability to get critical news about the governmentand the world, and, at this moment of uncertainty,what role the government should play.

Public Policy and Funding the NewsThe Government and the News MediaThroughout American history, the federalgovernment has worn many hats in itsrelationship with the press and the news industry:watchdog of power among news business owners;consumer advocate championing the news andinformation needs of underserved or neglectedcommunities; affirmative action catalyst forextending employment and ownership opportunities to minorities and women; regulator of thepublic airwaves; and provider of both direct andindirect subsidies that have been important piecesof the news industry’s economic health.State and local governments have also hadbeen benefactors of the news business. Oftenthey have provided subsidies such as income taxdeductions and credits. Local municipalities haveallowed newspaper vendor boxes on city sidewalks, often charging no fee. In other cases thebenefits have been indirect. One example: Nearlyall states have enacted shield-law protectionfor reporters against prosecutors’ subpoenas,something the federal government has so fardeclined to replicate.This rich menu of news media policies,statutes and regulations has fluctuated significantlyover the course of the nation’s history, followingthe swings of political sentiment and technology7development. The ups and downs of local radionews are a case in point. For decades the FederalCommunications Commission required broadcasters to carry news programs as part of theirpublic-interest obligation, including programs aboutimportant local issues. But those requirementshave long since been eliminated. Today local radionews is a rare occurrence. All-news stations arepresent in most large metropolitan areas, but inmany small to mid-size cities, talk-radio programs,most of them syndicated national shows, are theonly remnant of the heyday of radio news.The government has had impact of thatmagnitude across a wide swath of Americanmedia, from the granting of licenses for radio andtelevision broadcasts worth billions of dollars, toinvestments in infrastructure and technology thathave expanded, and helped create, mass audiencesfor the news. A new burst of infrastructuredevelopment is currently under way, with thefederal government spending at least 7 billion toexpand and upgrade high-speed Internet acrossthe country. This massive bet on new media maywell be a smart investment that will producelong-term benefits for the nation’s news andinformation needs. But in the short run, at least, itwill work to the disadvantage of print publishersand broadcasters, who need time to make thetransition to digital platforms.“Take money from the government?I don’t like to let anyone else pick upthe check.”—Mizell Stewart III, editor of theEvansville (Ind.) Courier & Press,in a Jan. 11, 2009, editorial titled“Newspaper Bailout? No Thanks”

8Public Policy and Funding the NewsOften journalists themselves aren’t aware ofhow much the legacy news businesses havebenefited – and continue to benefit – from thesupport of government at all levels. “Take moneyfrom the government?” wrote Mizell Stewart III,editor of the Evansville (Ind.) Courier & Press. “Idon’t like to let anyone else pick up the check.”13Similarly, Thomas Pounds, president andpublisher of the Toledo Free Press, wrote of agovernment bailout for the news media: “Not 1cent of government money should be spent.”14It’s true that the United States governmenthas never supported news-gathering to the extentsome countries have. Government support forAmerican public broadcasting, for example,amounts to cents on the dollar compared to manyEuropean and Asian countries. The same is truefor government support of newspapers. In 2009,for example, French President Nicolas Sarkozyannounced that free, one-year newspapersubscriptions would be given to those reachingtheir 18th birthdays – an initiative that is close tounthinkable in the United States. France also isweighing a proposal to tax Internet portals likeGoogle to even the playing field between Internetaggregators and news content providers.At the same time, it’s not true that the U.S.government doesn’t spend money supportingAmerican news business. It has always providedsignificant financial support. What’s salient nowis that those investments are in decline.As the news industry wavers,government support declinesThe late 1960s marked a high-water mark forthe government’s financial support for thenews business. At the time, the postal service wassubsidizing about three-fourths of the mailingcosts of newspapers and news magazines, at a costof about 400 million a year (nearly 2 billion inPostal subsidies plummetAs Postal Service subsidies for mailednewspapers and magazines decline 1967: 1.97 billion2006: 288 millionSources: U.S. Postal Service, Congressional Research Service(Note: Figures expressed in 2009 dollars.) publishers now shoulder nearly all costsof mailing newspapers and magazines.Subsidy level1971: 75 percent2006: 11 percentSource: U.S. Government Printing Officetoday’s dollars). This benefit, in combination withother government supports such as tax breaks andpaid public notices, amounted to a substantialfinancial boon for American news publishers. ThePostal Reorganization Act of 1970 marked a turningpoint. The landmark legislation immediatelyreduced publishers’ mailing subsidy by about half,and ever since, government’s financial support forthe commercial news business has been falling.Today, as many newspapers struggle for survival,the government appears certain to reduce itssupport still further by moving public notices tothe Web.These declines have not been a result of aconcerted policy to reduce government subsidiesand other financial support for the newsbusiness. Rather, they emerged from governmentfunding problems and from the development oftechnology that paved the way for reduced

Public Policy and Funding the Newssupport. Nevertheless, the impact is clear. At atime when news businesses are fighting tosurvive, the government has been reducing longstanding forms of support. Unless it changescourse, that support is likely to continue declining.Postal ratesLong before the United States was founded,the Postal Service was subsidizing the newsbusiness. It was in good measure the free-mailingprivileges conferred by many postmasters thatallowed a robust network of colonial newspapersto emerge. George Washington wanted all newspapers, in fact, to have 100 percent subsidizedmailing costs. The Postal Act of 1792 rejectedthe idea of a total subsidy, but it codified highlysubsidized and extremely low rates.What brought a halt to publishers’ receiving75 percent discounts on their mailed newsproducts was the financial crisis that engulfed thePostal Service in the late 1960s. Congresseventually decided to turn the post office into aquasi-private enterprise, to reduce the level ofgovernment support and to get out of the ratemaking business. Thus was the Postal RegulatoryLegal notices have beenespecially important to weeklyand other community newspapers. Their trade association,the National NewspaperAssociation, estimated in 2000that public notices accounted for5 to 10 percent of all communitynewspaper revenue.9Commission created in 1970, charged withensuring that periodicals, along with all otherclasses of mail, cover the “direct and indirectpostal costs attributable to that class or type.”Over the next four decades that principle wouldeat deeper and deeper into the historical subsidies enjoyed by news publishers. In one recentround of rate increases, small news magazineswere particularly hard-hit. Former publisherVictor Navasky said The Nation’s mailing costsshot up 500,000 in a single year – and came ata time when the magazine was already losingmore than 300,000 a year.Today, publishers’ discounts for their printednews products are down to 11 percent – less thanone-sixth of the level four decades earlier. Almostall of this benefit today goes to magazines.Meanwhile, newspapers’ total-market-coverageadvertising products are charged at rates thatexceed postal service costs by 300 million. Withthe Postal Service facing a 2010 deficitestimated at 7 billion, prospects appear high thatnewspaper and news magazines will continue toexperience increasingly higher rates.Public noticesLike postal subsidies, paid public notices tracetheir American origins to colonial days. Andlike postal subsidies, public notices mandated bythe government have been a critical component ofeconomic stability for newspapers. Yet they arealmost certain to shrink drastically as a source ofhigh-margin revenue for the commercial media.Governments at all levels are beginning to switchtheir public notices to the Web, a move that atbest means sharply reduced billings for publishers,and at worst means they could lose the businessaltogether.Public notices are government-required

10Public Policy and Funding the Newsannouncements that give citizens informationabout important activities. In most cases government mandates these notices of itself or ofsubordinate governments; in other cases theyestablish publication requirements for privatesector concerns. Typical public-notice laws applyto public budgets, public hearings, governmentcontracts open for bidding, unclaimed property,and court actions such as probating wills andnotification of unknown creditors. Public agencieshave required paid publication of this kind ofinformation for decades as a way to ensure thatcitizens are informed of critical actions.Historically, these fine-print notices havebeen a lucrative business for newspaper publishers,and have touched off heated bidding wars forgovernment contracts. Legal notices have beenespecially important to weekly and othercommunity newspapers. Their trade association,the National Newspaper Association, estimatedin 2000 that public notices accounted for 5 to 10percent of all community newspaper revenue.While other forms of advertising haveplummeted, public notices have been a bright spotfor publishers. Although small newspapers are thechief beneficiaries of public notices, nearly allnewspapers benefit to some extent. The Wall StreetJournal, for example, has a contract with thegovernment to print seized-property notices. In afour-week study, we discovered that thegovernment was the top purchaser, by columninches, of ad space in the Journal. It’s a business thenewspaper would like to expand. In 2009 it wasbattling with Virginia-area papers to get its regionaledition certified to print local legal notices.But the era of big money in public noticeswill almost certainly fade away. Proposals havebeen introduced in 40 states to allow local andstate agencies to shift publication to the Web, insome cases to the government’s own Web sites.Responding to The Wall Street Journal’s efforts toget a share of the public-notice revenue inVirginia, a circuit court judge in Norfolk said it“may be an opportune time for the GeneralAssembly to revisit the issue of notice bypublication in light of the variety of electronicmeans of mass communication available.” Themedia industry has beaten down many of theseinitiatives so far, but in a clear indication of futuretrends, the shift is beginning to happen. TheObama administration’s Justice Departmentannounced in 2009 that it would move federalasset forfeiture notices to the Web, saving 6.7million over five years.State and federal tax breaksAlso likely to decline are some of the taxbreaks given to news publishers, particularlythose tied to sales and use tax breaks fornewsprint, ink and other print-related expensesthat are becoming a smaller part of the publishingbusiness. All told, federal and state tax lawsforgive more than 900 million annually in taxesrelated to newspapers and magazines. Print publications received about 150 million in federal taxbreaks in the 2008 fiscal year – favorable rules forexpensing circulation expenditures (worth about 100 million) and special treatment of magazinereturns (worth about 50 million).Most of the money from tax breaks comes atthe state level. An analysis of tax data publishedin 37 of the 50 states showed that newspapers andmagazines received state tax breaks of nearly 800million in 2008. The largest amount, 625 million,is for a tax exemption on

support are the financing of public broadcasting in the United States and of the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and other outlets for audiences abroad. According to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting,about 1.14 billion of the 2.85 billion spent on public broadcasting (or about 40 percent of the total

Bellamy Young Ben Feldman Ben McKenzie Ben Stiller Ben Whishaw Beth Grant Bethany Mota Betty White Bill Nighy Bill Pullman Billie Joe Armstrong Bingbing Li Blair Underwood . David Koechner David Kross David Letterman David Lyons David Mamet David Mazouz David Morrissey David Morse David Oyelowo David Schwimmer David Suchet David Tennant David .

the newsletter for the cowan avenue elementary school community volume 61 issue 2 april 2007 Cowan Avenue is extremely pleased to announce that local children's book illustrator, Diane Greenseid, will be visiting our school on Friday, April 20th for two spe-cial student presentations. Ms. Greenseid grew up in Los Angeles, became

Geoffrey Smedley fonds. - 1951-2017. 3.71 m of textual records and other materials. Biographical Sketch Canadian sculptor Geoffrey Smedley was born in London, England in 1927, and studied at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College in London. He served in the British

School of Economics, Russian Federation Andrew Ainsworth, The University of Sydney, Australia Andrew Urquhart, University of Southampton, UK Anmar Pretorius, North-West University, South Africa Antonio David, IMF International Monetary Fund, USA Arash Aloosh, Neoma Business School, France Arnold R. Cowan, Iowa State University & Cowan

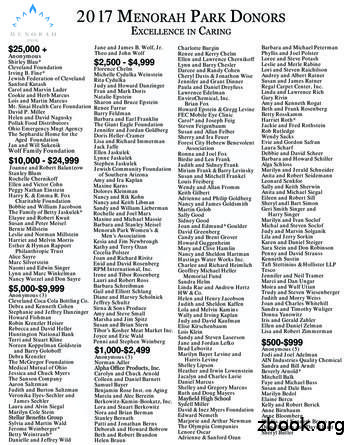

Stanley Coben Howard Cohen. Lottie Cohn Lynne and Philip Cohen. Nan Cohen and Daniel Abrams Lisa and Don Cohen. Nehemia Cohen . Maxine Cooper-Brand Miriam and Ronald Coppel. Coronet Vicki Coss. Elizabeth and Larry Coven Sara and Brad Coven. Erica and Greg Cowan Marcy and Richard Cowan. Maria Coyle Julie and Jeffrey Cristal. Michael Cristal .

Many biochemical tests were unique and tested different from Cowan and Steel, 2005; after confirmation of the S. pyogenes isolates identity by PCR, four of these isolates were positive to V.P. test, while S. pyogenes is negative accord-ing to Cowan and Steel [5]. Also, 17 (23.6%) isolates was Argenine hydrolysis test negative unlike what .

offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Use of Thesis This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. However the literary . to my family – Ruth, Alexandra, Elliot and Elizabeth. I did this for them. The influence of business i

The standards are neither curriculum nor instructional practices. While the Arizona English Language Arts Standards may be used as the basis for curriculum, they are not a curriculum. Therefore, identifying the sequence of instruction at each grade - what will be taught and for how long- requires concerted effort and attention at the local level. Curricular tools, including textbooks, are .