HIV Provider Smoking Cessation - Veterans Affairs

HIV Provider Smoking Cessation Handbook A Resource for Providers

HIV Provider Smoking Cessation Handbook A Resource for Providers

Acknowledgements The provider manual HIV Provider Smoking Cessation Handbook and the accompanying My Smoking Cessation Workbook were developed by the HIV and Smoking Cessation (HASC) Working Group of the Veterans Affairs Clinical Public Health (CPH). The authors primary goal was to develop materials promoting smoking cessation interventions, based on published principles of evidence- and consensus-based clinical practice, for use by HIV-care providers treating HIV patients who smoke. With permission from Dr. Miles McFall and Dr. Andrew Saxon, several materials used in these publications were modified from smoking cessation workbooks they developed for providers of patients with post traumatic stress disorder as part of the Smoking Cessation Project of the Northwest Network Mental Illness Research, Education & Clinical Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System. The Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline (Fiore, 2000) and the treatment model described by Richard Brown (2003) provided the foundation for their work and therefore indirectly ours as well.1 Many thanks to Kim Hamlett-Berry, Director of the Office of Public Health Policy and Prevention of CPH, for supporting this project; Hannah-Cohen Blair and Michelle Allen, research assistants, for their help organizing materials; and Leah Stockett for editing the manual and the workbook. As well, the HASC Working Group: Ann Labriola, Pam Belperio, Maggie Chartier, Tim Chen, Linda Allen, Mai Vu, Hannah Cohen-Blair, Jane Burgess, Maggie Czarnogorski, Scott Johns, and Kim Hamlett-Berry. Brown, R. A. (2003). Intensive behavioral treatment. In D. B. Abrams, R. Niaura, R. Brown, K. M. Emmons, M. G. Goldstein, & P. M. Monti, The tobacco dependence treatment handbook: A guide to best practices (pp. 118-177). New York, NY: Guilford Press. 1 Fiore, M. C., Bailey, W. C., Cohen, S. J., Dorfman, S. F., Goldstein, M. G., Gritz, E. R., Heyman, R. B., Jaén, C. R., Kottke, T. E., Lando, H. A., Mecklenburg, R. E., Mullen, P. D., Nett, L. N., Robinson, L., Stitzer, M. L., Tommasello, A. C., Villejo, L., & Wewers, M. E. (2000). Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

Table of Contents I. HIV and Smoking.1 Scope of the Problem. 4 Benefits of Smoking Cessation in HIV-Infected Smokers. 5 The HIV Care Provider’s Role. 6 Challenges to Cessation in HIV-Infected Smokers. 7 II. Smoking Cessation Interventions. 15 Effectiveness of Smoking Cessation Interventions. 17 Starting a Smoking Cessation Program for HIV‑Infected Veterans. 18 Smoking Cessation Behavioral Interventions. 18 Identifying Reasons to Quit. 21 III. R eal‑time Scripts for Brief Smoking Cessation Interventions. 25 Approaching Your Patients about Smoking Cessation. 27 Addressing Patient Concerns. 28 IV. Medications for Smoking Cessation. 35 Nicotine Pharmacology. 38 Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT). 39 Bupropion. 44 Varenicline. 46 V. R elapse Prevention and Smoking Cessation Maintenance. 57 Smoking is a Chronic, Relapsing Disorder. 59 Management of Withdrawal Symptoms. 60 i

Appendices. 65 Appendix A. Sample Smoking Cessation Programs. 66 One-on-one counseling. 68 Group Counseling. 72 Telephone Counseling. 74 Appendix B. Evaluating Smoking Cessation Programs. 89 Appendix C. Educational Materials and Additional Resources for Patients. 91 Smoking and HIV Fact Sheet. 91 Web and Telephone Resources. 94 Appendix D. Educational Materials and Additional Resources for Providers. 96 The 5 A’s of Smoking Cessation Interventions. 96 The 5 R’s of Enhancing Motivation to Quit Tobacco. 97 Sample: Smoking Cessation Program Screening Form. 99 Sample: HIV Clinic Form.100 Web Resources and Online Trainings. 101 Appendix E. FAQs.103 ii

Tables and Figures Table 1. T he 5 A’s of Brief Smoking Cessation Interventions. 19 Table 2. Enhancing Motivation to Quit Tobacco. 21 Table 3. Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence. 28 Table 4. S ample Responses to Patients’ Concerns About Smoking Cessation. 29 Table 5. S ample Scripts for Brief Smoking Cessation Conversations Between Patients and Providers. 31 Figure 1. E fficacy of Medications for Smoking Cessation. 38 Table 6. M edications for Smoking Cessation Available Through the VA National Formulary. 48 Table 7. S moking Withdrawal Symptoms and Recommendations. 60 Table 8. E ight-Session Smoking Cessation Intervention Schedule. 71 Table 9: P MTTCC Script for Initial Call (20-30 minutes). 75 iii

I. HIV and Smoking 1

I. HIV and Smoking CHAPTER SUMMARY Scope of the problem The incidence of smoking in HIV-infected Veterans is high and likely underreported Tobacco dependence is a chronic disorder that often requires repeated intervention and multiple attempts to quit Overall health consequences of smoking for those with HIV disease are more severe: Greater probability of cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions Greater risk of AIDS and non AIDS‑related illnesses Smoking increases the all-cause mortality of HIV-infected current smokers Benefits of smoking cessation in HIV-infected smokers Smoking cessation can reduce and prevent many smoking-related health problems Smoking is the most clinically important modifiable cardiovascular risk factor for HIV-infected smokers HIV-related symptoms decrease as early as three months after smoking cessation Every attempt to quit improves probability of eventual success The HIV care provider’s role Address smoking at every visit. Effectiveness starts with the clinical routine of: Documenting a patient’s smoking status Advising patients to quit and inquiring about their readiness at every visit Approaching smoking as a chronic illness, which includes monitoring repeated quit attempts and relapses Counseling and prescribing a combination of two smoking cessation medications Help patients access comprehensive care to address co-morbidities hindering their ability to quit Utilize an integrated model of care and provide a consistent message about smoking 3

I. HIV and Smoking CHAPTER SUMMARY Utilize a team approach as it results in greater efficacy in long-term follow up and represcribing smoking cessation medications Challenges to smoking cessation in HIV-infected smokers Higher incidence of co-morbidities such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, other psychiatric conditions, and substance and alcohol abuse Complications related to smoking habits may be a more serious immediate risk than HIV disease itself Culture of smoking higher in the military and among Veterans SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM Impact of Smoking on Morbidity and Mortality Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the United States.1-2 It is a chronic disorder that often requires repeated interventions and multiple attempts to quit. For HIV-infected individuals, smoking has an even greater health impact than for smokers in the general population or HIV‑infected nonsmokers3-4: 4 HIV-infected smokers have a greater probability of non-AIDS related diseases such as cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions (pneumothorax, pneumonia, lung cancer) and non-AIDS cancers.3-7 HIV-infected smokers have more AIDS-related illness such as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, tuberculosis, and oral candidiasis.8-10 HIV-infected smokers may have a decreased response to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and more rapid progression to AIDS.11-12 There may be an association between smoking and immunologic and virologic failure.13 Cigarette smoking has been found to be an independent predictor of non-adherence to ART.14 Studies have shown that HIV-infected individuals, including Veterans, who are current smokers have a significantly higher all-cause mortality than those who never smoked.15-16

I. HIV and Smoking ART has changed the prognosis for HIV-infected individuals from a fatal diagnosis to a manageable chronic illness.17-18 HIV-infected patients who adhere to ART are less likely to die from AIDS-related illnesses than from non‑AIDS‑related disease.18 Efforts to improve the health status and quality of life of individuals living with HIV is one of the highest treatment priorities. Such efforts need to include strategies for effective smoking cessation counseling and treatment.3,18 Incidence of Cigarette Smoking in the U.S. HIV-infected Population and HIV-infected Veterans Approximately 20% of the general U.S. population over 18 years old is a current smoker.19 The incidence of HIV-infected current smokers is thought to be much higher: HIV-infected individuals are 2-3 times more likely to be smokers than those who do not have the disease, with prevalence of smoking in the general HIV-infected population reported between 40-70%.20-23 The incidence of smoking in HIV-infected Veterans is also high and likely underreported. According to 2010 VHA reports of the 25,000 Veterans with HIV in VA care, 47% have smoked cigarettes at some time and approximately 25% are current smokers. However, self-report surveys indicate that more than 70% of these Veterans have smoked at some time and 46-51% are current smokers. These percentages may be even higher for combat Veterans.24-27 BENEFITS OF SMOKING CESSATION IN HIV-INFECTED SMOKERS Smoking cessation can reduce and reverse many of the well-known negative effects of tobacco use.28 There are also specific benefits for HIV-infected patients who quit smoking: Cigarette smoking is the most important modifiable cardiovascular risk factor among HIV-infected patients, more so even than the use of lipid‑lowering drugs or ART.29 The risk of cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients decreases with increased time since smoking cessation.30 The evaluation of a smoking cessation program at a 3-month follow up found that HIV-related symptom burden decreased as the amount of time without smoking increased.31 Every attempt to quit improves the probability of eventual success. 5

I. HIV and Smoking Effective Smoking Cessation Strategies Effective smoking cessation treatments that can significantly increase rates of long-term abstinence have been developed and tested.1,32 Patient success in quitting and staying smoke-free can be dramatically increased by implementing interventions that: Increase patient and staff awareness and education Use smoking cessation counseling plus smoking cessation medication Use two, rather than one, forms of smoking cessation medication Consistently identify (through documentation in the Computerized Patient Record System [CPRS]) and treat smokers Integrate smoking cessation into primary care THE HIV CARE PROVIDER’S ROLE HIV care providers have been slow to routinely assess their patients’ smoking status and monitor their quit attempts when compared to general primary care providers.22,33-34 In a study of VA HIV care providers35 they were: Less likely to identify their patients as current smokers Had lower confidence in their ability to influence the smoking habits of patients in their care Less likely to recognize current smoking in patients who reported dyspnea/cough, or with smoking-related diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, and bacterial pneumonia In an informal survey of providers at clinics for HIV-infected Veterans and studies of HIV care providers, it was shown that fewer than 50% of these providers followed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update (Clinical Practice Guideline) of providing patients with smoking cessation interventions such as counseling, referring them to a cessation program, or providing them with cessation medications.22,25,35 What We Can Do for HIV-infected Patients Who Smoke Researchers cite the importance of developing smoking cessation strategies specifically for HIV-infected smokers.36-38 Studies have shown the efficacy of integrating smoking cessation counseling into primary care and into clinics serving special populations such as those with PTSD and HIV disease.39-43 HIV 6

I. HIV and Smoking care providers can play a key role in helping their HIV patients quit smoking by: Recommending quitting, assessing readiness to quit, giving patients information about the risk of smoking and HIV disease and smoking cessation materials and monitoring quit attempts and smoking relapses. Smokers cite a physician’s advice to quit as an important motivating factor for attempting to quit.28 Administering two smoking cessation medications in combination with counseling. Assisting patients in resolving co-morbidities that may hinder their ability to quit smoking. Making referrals to specialists (e.g., mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, social workers) as needed. Re-prescribing smoking cessation medications after relapse. CHALLENGES TO CESSATION IN HIV-INFECTED SMOKERS HIV-infected individuals who smoke have a higher incidence of co-morbidities such as PTSD, depression and other psychiatric conditions, as well as substance and alcohol abuse.44-49 Some providers are hesitant to attempt smoking cessation in patients with serious co-morbidities, while others and some HIV‑infected smokers have misconceptions about the impact of light smoking in those with HIV disease. Several studies suggest that smoking cessation is possible in populations with serious co-morbidities, including HIV-infected individuals. For Veterans with PTSD who smoke, an integrated model of smoking cessation with primary care providers and staff that provided consistent care was found to be effective and superior to standard‑of‑care smoking cessation programs given separately from the primary care clinic.40,42 Studies in populations with psychiatric disorders and depression suggest at least moderate efficacy of smoking cessation and little evidence of exacerbation of these disorders.50-51 Approximately half of alcohol dependent individuals are daily smokers and a number of studies have evaluated concurrent treatment of nicotine dependence and alcohol use disorders.52 Overall, evidence indicates that smoking cessation interventions for individuals with alcohol use disorders are effective and have no detrimental effects on abstinence from alcohol.53 Study results are 7

I. HIV and Smoking mixed regarding optimal timing of smoking cessation interventions for alcohol use disordered individuals.54-55 Smoking status should be addressed for all individuals with alcohol use disorders and the following recommendations have been proposed:52,56 Smoking cessation interventions should be offered to all alcohol use disorder patients who smoke A menu of options about how and when to stop should be offered Timing of smoking cessation interventions (concurrent versus delayed) should be based on patient preference HIV-infected patients and their providers should know that the complications of their smoking habit may be a more serious risk to them than their HIV disease especially if patients are compliant with ART and otherwise well. Light smoking is dangerous to the health of those who smoke. The Surgeon General’s report on how tobacco causes diseases documents in great detail how both direct smoking and secondhand smoke causes damage not only to the lungs and heart, but to every part of the body.57 Researchers found that inhaling cigarette smoke from one cigarette causes immediate changes to the lining of blood vessels and that light smoking may be almost as detrimental as heavy smoking. Though the Department of Defense and the VA Veterans Health Administration have worked hard to reduce tobacco use, smoking remains widespread and deeply rooted in military culture and among Veterans.58 In one study, HIV‑infected Veterans who smoked were shown to socialize with other smokers to a greater extent than with non-smokers.25 Smoking cessation strategies need to continue to focus on changing the culture of smoking and find alternative and more positive forms of social interactions for Veterans that exclude tobacco use. 8

I. HIV and Smoking References: 1. Fiore, M. C., Jaén, C. R., Baker, T. B., Bailey, W. C., Benowitz, N. L., Curry, S. J., Dorfman, S. F., Froelicher, E. S., Goldstein, M. G., Healton, C. G., Henderson, P. Nez, Heyman, R. B., Koh, H. K., Kottke, T. E., Lando, H. A., Mecklenburg, R. E., Mermelstein, R. J., Mullen, P. D., Orleans, C. Tracy, Robinson, L., Stitzer, M. L., Tommasello, A. C., Villejo, L., & Wewers, M. E. (2008, May). Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Retrieved from http://www.healthquality. va.gov/tuc/phs 2008 full.pdf 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Tobacco use—Targeting the nation’s leading killer. At a Glance. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ /Tobacco AAG 2011 508. pdf 3. Aberg, J. A. (2009). Cardiovascular complications in HIV management: Past, present and future. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 50(1), 54-64. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2746916/?tool pubmed 4. Palella, F. J., Jr., Baker, R. K., Moorman, A. C., Chmiel, J. S., Wood, K. C., Brooks, J. T., Holmberg, S. D., & HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. (2006). Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: Changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 43(1), 27-34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16 5. Savès, M., Chêne, G., Ducimetière, P., Leport, C., Le Moal, G., Amouyel, P., Arveiler, D., Ruidavets, J. B., Reynes, J., Bingham, A., Raffi, F., & French WHO MONICA Project and the APROCO (ANRS EP11) Study Group. (2003). Risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection compared with the general population. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 37(2), 292-298. Retrieved from http://cid. oxfordjournals.org/content/37/2/292.long 6. Metersky, M. L., Colt, H. G., Olson, L. K., & Shanks, T. G. (1995). AIDS-related spontaneous pneumothorax: Risk factors and treatment. Chest, 108(4), 946951. Retrieved from 6.long 7. Arcavi, L., & Benowitz, N. L. (2004). Cigarette smoking and infection. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(20), 2206-2216. Retrieved from http:// archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/164/20/2206 8. Miguez-Burbano, M. J., Ashkin, D., Rodríguez, A., Duncan, R., Pitchenik, A., Quintero, N., Flores, M., & Shor-Posner, G. (2005). Increased risk of Pneumocystis carinii and community-acquired pneumonia with tobacco use in HIV disease. International Journal of Infectious Disease, 9(4), 208-217. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2004.07.010 9. Patel, N., Talwar, A., Reichert, V. C., Brady, T., Jain, M., & Kaplan, M. H. (2006). Tobacco and HIV. Clinics in Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 5(1), 193-207. doi: 10.1016/j.coem.2005.10.012 10. Palacio, H., Hilton, J. F., Canchola, A. J., & Greenspan, D. (1997). Effect of cigarette smoking on HIV-related oral lesions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology, 14(4), 338-342. 9

I. HIV and Smoking 11. Feldman, J. G., Minkoff, H., Schneider, M. F., Gange, S. J., Cohen, M., Watts, D. H., Gandhi, M., Mocharnuk, R. S., & Anastos, K. (2006). Association of cigarette smoking with HIV prognosis among women in the HAART era: A report from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. American Journal of Public Health, 96(6), 1060-1065. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC1470629/?tool pubmed 12. Neiman, R. B., Fleming, J., Coker, R. J., Harris, J. R., & Mitchell, D. M. (1993). The effect of cigarette smoking on the development of AIDS in HIV-1seropositive individuals. AIDS, 7(5), 705-710. 13. Royce, R. A., & Winkelstein, W., Jr. (1990). HIV infection, cigarette smoking and CD4 T-lymphocyte counts: Preliminary results from the San Francisco Men’s Health Study. AIDS, 4(4), 327-333. 14. Shuter, J., & Bernstein, S. L. (2008). Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10(4), 731-736. doi: 10.1080/14622200801908190 15. Lifson, A. R., Neuhaus, J., Arribas, J. R., van den Berg-Wolf, M., Labriola, A. M., Read, T. R., & INSIGHT SMART Study Group. (2010). Smoking‑related health risks among persons with HIV in the strategies for management of antiretroviral therapy clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1896-1903. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC2936972/?tool pubmed 16. Crothers, K., Goulet, J. L., Rodriguez-Barradas, M. C., Gibert, C. L., Oursler, K. A., Goetz, M. B., Crystal, S., Leaf, D. A., Butt, A. A., Braithwaite, R. S., Peck, R., & Justice, A. C. (2009). Impact of cigarette smoking on mortality in HIV-positive and HIV-negative veterans. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(3 Suppl), 40-53. Retrieved from http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3118467/?tool pubmed 17. Mocroft, A., Ledergerber, B., Katlama, C., Kirk, O., Reiss, P., d’Arminio Monforte, A., Knysz, B., Dietrich, M., Phillips, A. N., Lundgren, J. D., & EuroSIDA study group. (2003). Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: An observational study. The Lancet, 362(9377), 22-29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13802-0 18. Niaura, R., Shadel, W. G., Morrow, K., Tashima, K., Flanigan, T., & Abrams, D. B. (2000). Human immunodeficiency virus infection, AIDS, and smoking cessation: The time is now. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 31(3), 808‑812. Retrieved from g 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011, Sept. 9). Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking amount adults aged 18 years --- United States, 2005—2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(35), 1207-1212. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6035a5. htm?s cid mm6035a5 w 20. Kwong, J., & Bouchard-Miller, K. (2010). Smoking cessation for persons living with HIV: A review of currently available interventions. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 21(1), 3-10. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.03.007 21. Mamary, E. M., Bahrs, D., & Martinez, S. (2002). Cigarette smoking and the desire to quit among individuals living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 16(1), 39-42. doi: 10.1089/108729102753429389 10

I. HIV and Smoking 22. Tesoriero, J. M., Gieryic, S. M., Carrascal, A., & Lavigne, H. E. (2010). Smoking among HIV positive New Yorkers: Prevalence, frequency, and opportunities for cessation. AIDS and Behavior, 14(4), 824-835. doi: 10.1007/ s10461-008-9449-2 23. Drach, L., Holbert, T., Maher, J., Fox, V., Schubert, S., & Saddler, L. C. (2010). Integrating smoking cessation into HIV care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(3), 139-140. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0274 24. Justice, A. C., Dombrowski, E., Conigliaro, J., Fultz, S. L., Gibson, D., Madenwald, T., Goulet, J., Simberkoff, M., Butt, A. A., Rodriquez‑Barradas, M. C., Gibert, C. L., Oursler, K. A., Brown, S., Leaf, D. A., Goetz, M. B., & Bryant, K. (2006). Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS): Overview and description. Medical Care, 44(8 Suppl 2), S13–S24. Retrieved from 2/?tool pubmed 25. Reisen, C., Bianchi, F. T., Cohen-Blair, H., Liappis, A. P., Poppen, P. J., Zea, M. C., Benator, D. A., & Labriola, A. M. (2011). Present and past influences on current smoking among HIV-positive male veterans. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13(8), 638-645. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr050 26. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2009, December). The state of care for Veterans with HIV/AIDS. Retrieved from asp 27. Crothers, K., Goulet, J. L., Rodriguez-Barradas, M. C., Gibert, C. L., Oursler, K. A., Goetz, M. B., Crystal, S., Leaf, D. A., Butt, A. A., Braithwaite, R. S., Peck, R., & Justice, A. C. (2009). Impact of cigarette smoking on mortality in HIV-positive and HIV-negative veterans. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(3 Suppl), 40-53. Retrieved from http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3118467/?tool pubmed 28. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. (1990). The health benefits of smoking cessation [DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 90-8416]. Retrieved from http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBCT.pdf 29. Grinspoon, S., & Carr, A. (2005). Cardiovascular risk and body-fat abnormalities in HIV-infected adults. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(16), 48-62. Retrieved from http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/ NEJMra041811 30. Petoumenos, K., Worm, S., Reiss, P., de Wit, S., d’Arminio Monforte, A., Sabin, C., Friis-Møller, N., Weber, R., Mercie, P., El-Sadr, W., Kirk, O., Lundgren, J., Law, M., & D:A:D Study Group. (2011). Rates of cardiovascular disease following smoking cessation in patients with HIV infection: Results from the D:A:D study(*). HIV Medicine, 12(7), 412-421. doi: 10.1111/j.14681293.2010.00901.x 31. Vidrine, D. J., Arduino, R. C., & Gritz, E. R. (2007). The effects of smoking abstinence on symptom burden and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21(9), 659-666. doi: 10.1089/ apc.2007.0022 32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1992). Public health focus: Effectiveness of smoking-control strategies -- United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 41(35), 645-647, 653. Retrieved from http://www. cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00017511.htm 11

I. HIV and Smoking 33. Fultz, S. L., Goulet, J. L., Weissman, S., Rimland D., Leaf, D., Gibert, C., Rodriquez-Barradas, M. C., & Justice, A. C. (2005). Differences between infectious diseases-certified physicians and general medicine-certified physicians in the level of comfort with providing primary care to patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 41(5), 738-743. Retrieved from http://cid. oxfordjournals.org/content/41/5/738.long 34. Crothers, K., Goulet, J. L., Rodriguez-Barradas, M. C., Gibert, C. L., Butt, A. A., Braithwaite, R. S., Peck, R., & Justice, A. C. (2007). Decreased awareness of current smoking among health care providers of HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(6), 749-754. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2219870/?tool pubmed 35. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Public Health Strategic Health Care Group. (2011, January). Survey of HIV-care providers. 36. Nahvi, S., & Cooperman, N. A. (2009). Review: The need for smoking cessation among HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(3 Suppl), 14-27. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2704483/?tool pubmed 37. Gritz, E. R., Vidrine, D. J., & Fingeret, M. C. (2007). Smoking cessation a critical component of medical management in chronic disease populations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(6 Suppl), S414-S422. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.013 38. Borrelli, B. (2010). Smoking cessation: Next steps for special populations research and innovative treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(1), 1-12. doi: 10.1037/a0018327 39. Goldstein, A., Gee, S., & Mirkin, R. (2005, Spring). Tobacco dependence program: A multi-faceted systems approach to reduce tobacco use among Kaiser Permanente members in northern California. The Permanente Journal, 9(2), 9-18. Retrieved from http://www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/PDF/ Spring2005.pdf 40. McFall, M., Saxon, A. J., Thompson, C. E., Yoshimoto, D., Malte, C., Straits‑Troster, K., Kanter, E., Zhou, X. H., Dougherty, C. M., & Steele, B. (2005). Improving the rates of quitting smoking for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(7), 1311-1319. Retrieved from http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/article. aspx?volume 162&page 1311 41. Thompson, R. S., Michnich, M. E., Friedlander, L., Gilson, B., Grothaus, L. C., & Storer, B. (1988). Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions integrated into primary care practice. Medical Care, 26(1), 62-76. 42. McFall, M., Saxon, A. J., M

Table 9: PMTTCC Script for Initial Call (20-30 minutes).75. 1 I. HIV and Smoking. 3 I. HIV and Smoking CHAPTER SUMMARY Scope of the problem The incidence of smoking in HIV-infected Veterans is high and . Smoking cessation can reduce and reverse many of the well-known negative effects of tobacco use.28 There are also specific benefits for .

Smoking Cessation . Smoking cessation can have an immediate impact on the economic and public health consequences of tobacco use. This chapter examines current evidence for cessation support and best practices and their implementation in countries around the world. Specifically, the chapter discusses the following topics:

Mosby’s Nursing Consult - Smoking Cessation o Thompson: Mosby’s Clinical Nursing, 5th ed. o Primary Care, 4th ed. Buttaro o ExitCare Patient Education Handouts Smoking Cessation Smoking Cessation – Tips for Success Approved by: Patient Education

Public Health England - Stop smoking services: models of delivery . The National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training - Very Brief Advice training module . NHS RightCare - Smoking cessation decision aid Effectiveness of a hospital -initiated smoking cessation programme: 2- year health and healthcare outcomes : NHS London Clinical Senate -

The ABC approach does not replace specialist smoking cessation treatment. Smoking cessation specialists, such as Quitline staff, Aukati Kai Paipa kaimahi, and health care workers who have bee

smoking cessation programs. Taped support messages are also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Quit Programs, Counseling and Support Groups Smoking cessation programs are designed to help smokers recognize and cope with problems they face when they are trying to quit. They also offer emotional support and encouragement.

smoking cessation programs. Taped support messages are also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Quit Programs, Counseling and Support Groups Smoking cessation programs are designed to help smokers recognize and cope with problems they face when they are trying to quit. They also offer emotional support and encouragement.

Before we get into the detail there are some commonalities of all stop smoking medicines that you need to know. Stop smoking medicines increase quit rates All stop smoking medicines increase the chances of stopping smoking for good. Smokers should be encouraged to use one of the licensed stop smoking medicines to aid them in stopping smoking.

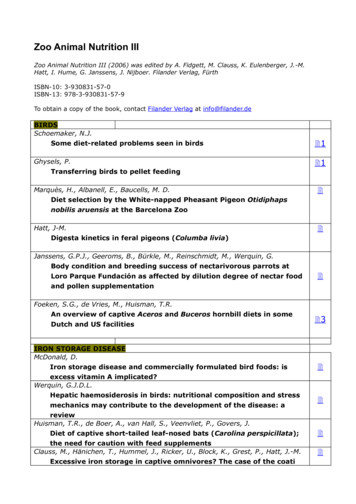

Zoo Animal Nutrition III (2006) was edited by A. Fidgett, M. Clauss, K. Eulenberger, J.-M. Hatt, I. Hume, G. Janssens, J. Nijboer. Filander Verlag, Fürth ISBN-10: 3-930831-57-0 ISBN-13: 978-3-930831-57-9 To obtain a copy of the book, contact Filander Verlag at info@filander.de BIRDS Schoemaker, N.J. Some diet-related problems seen in birds 1 Ghysels, P. Transferring birds to pellet feeding 1 .