Regulation Of Water Supply And Sanitation In Bank Client Countries

Public Disclosure Authorized DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized WATER GLOBAL PRACTICE Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries A Fresh Look Public Disclosure Authorized Discussion Paper of the Water Supply and Sanitation Global Solutions Group, Water Global Practice, World Bank NOVEMBER 2018 Yogita Mumssen, Gustavo Saltiel, Bill Kingdom, Norhan Sadik, and Rui Marques

About the Water Global Practice Launched in 2014, the World Bank Group’s Water Global Practice brings together financing, knowledge, and implementation in one platform. By combining the Bank’s global knowledge with country investments, this model generates more firepower for transformational solutions to help countries grow sustainably. Please visit us at www.worldbank.org/water or follow us on Twitter at @WorldBankWater.

Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries A Fresh Look Discussion Paper of the Water Supply and Sanitation Global Solutions Group, Water Global Practice, World Bank NOVEMBER 2018 Yogita Mumssen, Gustavo Saltiel, Bill Kingdom, Norhan Sadik, and Rui Marques

2018 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Please cite the work as follows: Mumssen, Yogita, Gustavo Saltiel, Bill Kingdom, Norhan Sadik, and Rui Marques. 2018. “Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries: A Fresh Look.” World Bank, Washington, DC. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org. Cover design: Jean Franz, Franz & Company, Inc.

Contents Acknowledgments v vii Abbreviations Executive Summary 1 Objectives of this Discussion Paper 1 Background 1 WSS Regulation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 1 Regulatory Objectives 2 Regulatory Forms 2 Regulatory Functions 3 Strengthening Regulation: The Way Forward 5 Notes 7 Chapter 1 Introduction Chapter 2 An Overview of Traditional WSS Regulatory Models and Applicability for Low- and Middle-Income Countries 9 11 Note 17 Chapter 3 3.1 Regulation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: View from Key Literature Regulatory Objectives 19 19 3.2 Regulatory Forms 22 3.3 Regulatory Functions 26 3.4 Aligning Institutions and Incentives with the Enabling Environment 33 Notes 36 Chapter 4 WSS Regulation in Practice in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 37 4.1 Regulatory Objectives 37 4.2 Regulatory Forms 38 4.3 Regulatory Functions 44 4.4 Aligning Institutions and Incentives with the Enabling Environment 60 Notes 63 Chapter 5 Prioritizing Key Challenges of WSS Regulation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 5.1 65 Context Matters 65 5.2 Regulatory Objectives 66 5.3 Regulatory Forms 66 Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries iii

5.4 Regulatory Functions 66 5.5 Regulation Fit for Purpose: What Does it Take? 68 5.6 Strengthening Regulation: The Way Forward 70 Notes 73 Appendix A 75 Appendix B 77 References 95 Boxes 2.1. Approach to Water Sector Regulation in New South Wales 15 3.1. Link between WSS Regulation and WRM 23 4.1. Effectiveness of Multisector Regulators: Inconclusive Evidence 43 4.2. Regulation of Quality of WSS Services in the State of Ceará, Brazil 52 4.3. 57 Pro-Poor Mechanisms in LMICs Figures 3.1. Schematic Aligning Institutions and Incentives for WSS Services 34 4.1. Regulatory Domains in WSS in South Africa 45 4.2. Senegalese WSS Regulation by Contract 53 4.3. 60 Interlinkages between Policy, Institutions, and Regulation Tables 1.1. Range of WSS Regulatory Frameworks in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 3 2.1. Traditional Regulatory Models in Selected OECD Countries 13 3.1. Range of WSS Regulatory Frameworks in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 25 4.1. Incidence of Independent WSS Regulators in Low- and Middle-Income Countries 40 4.2. Examples of Regulatory Arrangements in Selected Countries 46 4.3. 56 Summary of Stakeholder Engagement Practices in Latin America 4.4. Summary of Approaches in Regulation of On-Site Sanitation in Select Low- and Middle-Income Countries 59 4.5. Transparency Practices in the Regulatory Agencies of Latin America 62 5.1. Regulatory Assessment Tools and Guidelines 73 A.1. Performance Management Implemented by Regulators in Latin America 75 A.2. Subsidization Mechanisms in Latin American Countries and the Role of Regulators 76 B.1. 77 iv Typology of WSS Regulatory Frameworks and Tools in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries

Acknowledgments T his discussion paper is a product of the World discussion paper were Yogita Mumssen, Gustavo Bank Water Global Practice’s Global Study on Saltiel, Bill Kingdom, Norhan Sadik, and Rui Marques. Policy, Institutions, and Regulatory Incentives This work was carried out under the general direction for Water Supply and Sanitation Service Delivery, and and guidance of Maria Angelica Sotomayor and Bill forms part of the Water Supply and Sanitation Global Kingdom. The team is also grateful for the comments Solutions Group (WSS GSG) agenda. This work was and suggestions from Alexander Bakalian, Chloe Oliver financed by the World Bank’s Global Water Security and Viola, Daniel Camos Daurella, Katharina Gassner, and Sanitation Partnership and the Swiss State Secretariat Oscar Pintos. The team would like to acknowledge the for Economic Affairs (SECO). valuable inputs and support provided by Pascal Saura, This discussion paper was prepared by a team led by Yogita Mumssen and Gustavo Saltiel. Authors of the Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries Berenice Flores, Clémentine Marie Stip, Ilan Adler, and Pinki Chaudhuri. v

Abbreviations AIAS Administration for Water Supply and Sanitation Infrastructure (Administracao De Infra-Estruturas de Agua E Saneamento; Mozambique) AMCOW African Ministers Council on Water ARCE Regulatory Agency of Delegated Public Services of the State of Ceará (Agência Reguladora de Serviços Públicos Delegados do Estado do Ceará, Brazil) ARESEP Regulatory Authority of Public Services (Autoridad Reguladora de los Servicios Públicos, Costa Rica) AySA Argentina Water and Sanitation Utility (Agua y Saneamientos Argentinos, Argentina) ARR annual revenue requirement BSWSC Bauchi State Water Supply Company (Nigeria) CA concession agreements CAPEX capital expenses CBO community-based organization CCG customer challenge group CLTS community-led total sanitation CRA Water Regulatory Council (Conselho de Regulação de Águas; Mozambique) CRA National Water Regulatory Commission (Comisión de Regulación de Agua Potable y Saneamiento Básico, Colombia) CU commercialized utility DCM decision of the council of ministers DMF delegated management framework DPWA Department of Public Works and Highways DTF devolutionary trust fund ENRESP Public Services Regulatory Authority (Ente Regulador de Servicios Publicas; Salta, Argentina) EPI economic policy instrument ERSAR Water and Waste Services Regulation Authority (Entidade Reguladora dos Servicos de Aguas e Residuos; Portugal) ESC Essential Services Commission (Australia) EU European Union Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries vii

EWRA Egypt Water Regulatory Authority EWURA Energy and Water Utilities Regulatory Authority (Tanzania) FCS fragile and conflict affected states FINDETER Financial Development Territorial SA (Financiera del Desarrollo Territorial SA; Colombia) GP global practice IBNET international benchmarking network IBT increasing block tariffs IDT institutional diagnostic tool IEG independent evaluation group IRAR Institute for Regulation of Water and Waste (Instituto Regulador de Águas e Resíduos; Portugal) IPART Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (Australia) JVA Jordan Valley Authority KPI key performance indicator LG local government LGU local government unit LICs low-income countries LMICs low- and middle-income countries (authors combine LIC, LMIC and MIC) LWUA Local Water Utilities Administration (Philippines) MDG millennium development goal MWSS Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage Services (Philippines) NGO non-governmental organization NPG new public governance NRC National Regulatory Council (Australia) NRW non-revenue water NPM new public management NSW New South Wales NWASCO National Water Supply and Sanitation Council (Zambia) NWP national water policy viii Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries

NWRB National Water Regulatory Board (Philippines) O&M operation and maintenance OBA output-based aid ODA official development assistance ODI outcome delivery incentive OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Ofwat Water Services Regulation Authority (England and Wales) ONEA National Water and Sanitation Utility (Office National de L’Eau et de L’Assainissement; Burkina Faso) OPDM Public Decentralised Municipal Agency (Organismo Público Descentralizado Municipal; Mexico) OPEX operating expenses PBC performance-based contracting PBF performance-based financing PBGS performance-based grant system PC performance commitment PDAM local government-owned WSS utility (Perusahaan Daerah Air Minum; Indonesia) PENSAAR Strategic Plan for Water Supply and Sanitation Sector (Plano Estratégico para o Setor de Abastecimento de Água e Saneamento de Águas Residuais, Portugal) PIR policies, institutions and regulation PLANSAB National Basic Water and Sanitation Plan (Plano Nacional de Saneamento Básico, Brazil) PPP public-private partnership PPWSA Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority (Cambodia) PSP private sector participation PUC public utility commission PURC Public Utilities Research Center PWA Palestinian Water Authority PWRF Philippines Water Revolving Fund RBF results-based financing RIA regulatory impact analysis Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries ix

RoA return on assets RPI retail price index SABESP The State Water Utility of Sao Paolo (Companhia de Saneamento Básico do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil) SDE Senegalese Water (Senegalaise des Eaux, Senegal) SDG sustainable development goal SECO Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SIM service incentive mechanism SISS Superintendence of Sanitary Services (Superintendencia de Servicios Sanitarios, Chile) SLG service level agreement SNIS National Information System for WSS (Sistema Nacional de Informacoes Sobre Saneamento, Brazil) SOE state-owned enterprise SONES National Water Company of Senegal (Société Nationale des Eaux du Sénégal) SSPD Superintendence of Public Services (Superintendencia de Servicios Publicos Domiciliarios, Colombia) SUNASS National Water and Sanitation Sector Regulator (Superintendencia Nacional de Servicios de Saneamiento, Peru) SWC Sydney Water Company SWSC Swaziland Water Services Corporation TPA traditional public administration TRASS Administrative Court for Complaints Resolution; Peru TTL task team leader UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund URSEA Energy and Water Utilities Regulator (Unidad Reguladora de Servicios de Energía y Agua, Uruguay) USO universal service obligations WACC weighted average cost of capital WASH water supply, sanitation, and hygiene WASREB Water Sector Regulatory Board (Kenya) WDR World Development Report WICS Water Industry Commission for Scotland x Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries

WRA Water Regulatory Authority (Albania) WRM water resource management WSRC Water Sector Regulatory Council (Palestine) WSSRC Water Supply and Sanitation Regulatory Commission (Bangladesh) WSS water supply and sanitation WSS GSG Water Supply and Sanitation Global Solutions Group WWGs water watch groups ZINWA Zimbabwe National Water Authority Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries xi

Executive Summary Objectives of this Discussion Paper This discussion paper is a supplement to the 2018 World Bank global study Aligning Institutions and Incentives for Sustainable Water Supply and Sanitation (WSS) Services, recently published by the World Bank’s the competing interests of the various stakeholders. Economic regulation refers to the “setting, monitoring, enforcement and change in the allowed tariffs and service standards for utilities” (Groom et al., 2006). Water Global Practice. The Global Study promotes The United Kingdom and Australia both established holistic approaches in shaping WSS sector policies, independent regulators in the 1980s and 1990s as institutions and regulation by considering the wider part of a package of reforms built around privatiza- political economy and governance framework to tion or commercialization. Regulation of private util- incentivize sustainable actions. ities has existed for many decades in the United In particular, this paper examines how lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs)1 can successfully establish or improve regulation of the WSS sector by taking into account political, legal, and institutional States, while contract regulation has historically predominated in France and Spain. These international reforms of WSS services often inspired similar models of regulation in LMICs. realities. Rather than importing “best practice” models Yet, the context for regulation in LMICs was much dif- from OECD (or broadly, upper-income) countries, ferent from where the models originated—in terms of experience has emphasized the importance of devel- access, quality of service, data availability, human oping “best fit” regulatory frameworks that are aligned capacity, governance and institutional context, to with the policy and institutional frameworks of a name a few. Regulatory initiatives in OECD countries LMIC’s WSS sector. This ensures that new regulations were also built on foundations such as trusted institu- are embedded within the country’s broader political tions, well-defined property rights, and a formal sys- economy and governance frameworks. tem This paper does not seek to offer definitive conclusions, rather it provides suggestions on the way forward, along with a phased approach to regulatory reform. Importantly, it sheds light on the issues that warrant further investigation to determine the future of WSS regulation in LMICs. of contract and corporate law, creating predictability and stability for investors. In LMICs legal and administrative institutions are less developed, with weaker enforcement, transparency, and accountability, and local history, customs, and traditions that can play a significant role in determining reform outcomes. Background WSS Regulation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Regulation is a policy intervention that aims to pro- For regulations to be effective, their goals, form, and mote sector goals in the public interest – balancing function must align with the country’s established Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries 1

institutional framework, and consider the realities of sector already exists, the policy objective may relate its political economy. Otherwise, governments may more to efficient service delivery, environmental merely create the illusion of reform. This is often goals, and accessing commercial finance. In LMICs, described as “isomorphic mimicry,” referring to when the government’s objectives may be similar but pri- governments suggest reform but do not necessarily oritized in a different order, or else be completely implement it, for example by only making changes in unrelated. the external form of policies and/or organization rather than their actual functions. For example, some common regulatory objectives for the WSS sector in LMICs include: Perhaps the biggest challenge to successfully importing regulation models from OECD countries to LMICs derives from significant differences in ownership and legal structures. WSS providers in LMICs are dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or are run by municipal governments, whereas private operators or ring-fenced corporatized SOEs domi- Increasing access, especially to peri-urban and rural areas, and to poor and vulnerable groups; Improving quality of service delivery; Improving efficiency of service providers; and Securing access to capital markets for sector financing. nate OECD c ountries. The incentive mechanism is quite different between public and private operators: Private utilities. The ability of a private operator to finance itself and provide fair returns to shareholders is of critical importance. This provides private utilities with clear incentives to improve efficiency, deliver on improvements demanded by customers, and expand networks to new customers. Regulatory Forms Over the past few decades, LMICs have predominantly imported or designed new WSS regulations in the form of a dedicated sector regulatory agency, often with aspirations of independence. But the most effective regulatory forms in these countries have been varied, and depend on a multitude of factors, including the country’s legal system, sector policies, governance structure, the extent of SOEs and municipal-run utility services. Financial sus- decentralization, and whether national SOEs already tainability is balanced with stated or unstated social exist. and political objectives and weak accountability. Incentives are less clear and often lead to low levels of service quality, coverage, efficiency, and financial sustainability. Regulatory Objectives Moreover, LMICs often confront distinct challenges in terms of limited administrative capacity and budgetary resources. Factors such as poorly trained staff; insufficient information; lack of financial resources; inadequate civil service rules; and unrealistic time constraints can all impact the capacity of A government’s broader policy objectives deter- regulators to effectively implement their mandated mines what role regulation will play in achieving responsibilities. In the absence of institutionalized them, so gaining clarity on sector objectives is a crit- coordination mechanisms, there is an increased risk ical first step. Policy objectives in OECD countries of duplicating roles, and sometimes a lack of clarity may be quite different from those in LMICs. In the regarding institutional mandates and policies (see former case, where universal coverage for the WSS table 1.1). 2 Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries

TABLE 1.1. Range of WSS Regulatory Frameworks in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Regulatory Frameworks Description Sector Specific WSS regulator mandated to oversee private and public service providers. Roles and responsibilities may National or State include issuing licenses, setting and monitoring performance standards, setting tariffs, ensuring consumer Regulator protection, performing audits, evaluating business plans, building capacity, and reporting regularly to government authorities. Sector-specific regulators operate across a vast number of countries including Colombia, Egypt, Mozambique, and Peru. In large federal countries where WSS services and regulation are at the state level, the national regulatory model outlined above can be replicated at the state level. Multi-Sector Regulator Multisector regulation provides scale economies, consistent regulatory processes, and knowledge exchange between different sectors. Although the multisector regulator might avoid regulatory capture by a specific sector; certain sectors may not receive sufficient attention. Ghana has an established multisector regulator responsible for oversight of energy and water sectors. Tanzania, Angola and Cape Verde have similar regulators, with varying degrees of success. In Brazil, 14 states have established multisector public services regulators which include, besides the water sector, also the transportation and energy sectors. Self-Regulation at the This takes many forms but essentially the public entity providing the service (municipal department, agency, Municipal Level corporation) is overseen by the municipal, council, or a designated governing board. In some cases, a municipally owned ring-fenced corporation is responsible for service delivery, and oversight is carried out by the board of directors. The board represents the municipality and has the power to approve tariffs. Managerial authority is delegated to the CEO of the utility, and oversight is undertaken by a municipal governing board. Cambodia offers an example of selfregulation whereby policy making, service delivery, and regulatory functions are implemented by the PPWSA. Government Traditional form of WSS regulation through the same ministry (or Secretary of State) that develops policy and Department operates water systems. Regulation by Contract Performance contracts between the government and a private entity responsible for O&M of the WSS facilities. Monitoring entity performs functions similar to that of a regulator, although with significantly less professional support staff and discretion. Burkina Faso implements a performance contract arrangement between the service supplier and the government. The contract specifies performance targets such as expansion of services to informal areas. Regulatory Functions mobilize finance for improving coverage or quality Regulators can use numerous tools to incentivize WSS service providers to achieve sector objectives. The of service. Regulators can help improve this situation in several ways: effectiveness of these tools, however, primarily a. Build a solid analytical foundation. This entails plac- depends on the degree to which they are aligned with ing an initial focus on quality regulation until the and responsive to the sector’s policy and institutional required financial data and capacity levels are met framework. Key regulatory functions and their associ- by utilities. In Colombia, the government focused ated tools and approaches found in LMICs include initially on acquiring unit costs and standardizing improving financial sustainability; improving service the accounting norms used by utilities. This enabled provider it to introduce efficiencies to fully reflect operational performance; increasing accountability, transparency, and consumer voice; and pro-poor regulation. Improving Financial Sustainability costs first and then increasingly investments. b. Financial modeling underpins effective tariff setting. Burkina Faso successfully implemented a financial model agreement with a private utility company If a service provider is financially weak then it can- that is stipulated in a performance-based manage- not properly operate and maintain its assets, nor ment contract. Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries 3

c. Assess creditworthiness. In Kenya, the regulator requirements, and monitoring and auditing arrange- prepared 43 shadow credit ratings to inform inves- ments. Risks remain in relation to contract enforce- tors of the risk of investing in Kenyan WSS utilities. ment, risk management, and risk sharing. This played a key role in facilitating increased access to commercial finance for utilities. d. Corporatization. This enables the introduction of performance-based remuneration for staff and man- d. Attract private sector investment. Securing private agers and facilitates results-based approaches. sector investment is unlikely without improved Uganda provides an interesting example of using a financial corporate charter with clear KPI targets and incen- sustainability through regulation. Colombia’s tariff reforms were to a large degree effective in stimulating private sector participation. e. Client and service provider contracts. Such contracts allow for clearer performance improvement targets Improving Service Provider Performance Monitoring the performance of WSS service delivery by utilities can help improve performance when linked to some form of reward or penalty, even if it is simply shining the light on good or poor performers, known as sunshine regulation. LMICs use a multitude of performance management tools with varying degrees of success, including: a. Benchmarking. This creates the potential for incen- to be set. For example, in Brazil all state companies have contracts with municipalities, which are the owners of the assets. In Argentina, the state-run utility Agua y Saneamientos (AySA) and most other utility companies have contracts with provinces that are the owners of the WSS facilities. Increasing Accountability, Transparency, and Consumer Voice tives to improve performance through associated Regulators play an instrumental role in establishing rewards and penalties. A prerequisite for bench- consumer protection and engagement practices that marking is the establishment of a reliable data col- support improved accountability and transparency in lection system. In Peru, weighted performance service provision. A variety of successful mechanisms indicators are calculated to a single performance are used across LMICs, ranging from Water Watch score. In Chile, performance results are reflected in Groups (WWGs) comprised of local volunteers in procedure for setting tariffs. Zambia to public hearing and consultation processes b. Licensing. This allows regulators to monitor agreed upon service standards. In Albania, the Water Regulatory Authority is responsible for ensuring service providers meet stipulated service standards. formance indicators (KPIs) can be used that are used widely across Latin America. Pro-Poor Regulation Instruments that can i ncentivize expanded access include: c. Performance- and results-based contracts. Key perin public-public or public-private contracts to improve performance. In Burkina Faso, the government implemented three-year contract plans with twenty 4 tives for public utilities. a. Universal service standards. This involves setting clear access targets with enforceable penalties should targets be unmet. b. Provision of output-based aid (OBA): Regulation (by to thirty KPIs for technical, financial, and commer- contract, agency, or other) could allow for cial performance. Performance contracts are most performance-based instruments such as OBA to effective when they include simple agreements, subsidize, for example, the costs of installing clear responsibilities, realistic targets, reporting water connections for the poor, a p ractice used Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries

in institutional and administrative capacities, and its many countries including Colombia, Kenya, legal and regulatory frameworks. Morocco, the Philippines, and Uganda. This supports incentive policies while insuring—through appropriate financial modeling—the sustainability of the c. Understand the political economy of the country and sector. This requires identifying how the public interventions. sector has developed over time, including cultural influences and attitudes toward WSS services. c. Differentiated service standards and alternative service providers. For example, in 2003, Zambia estab- d. Design interventions that are fit for purpose. This lished the Devolutionary Trust Fund (DTF) to ensures that interventions are not overly complex improve WSS coverage in peri-urban and low- income for the given context and capacities. areas, administered by a regulatory agency called the National Water Supply and Sanitation Council e. Provide sufficient capacity support. This ensures that reform objectives are realized. Capacity building (NWASCO). The DTF targets low-cost, high-impact projects such as water kiosks, water meters, and improvements on pipelines and sewerage pipes. should be informed by realities on the ground. f. Ensure there is sufficient financial capacity. Doing so will sustain results and guarantee the human d. Social tariffs. In cases where low-income households resources required to implement the desired already have access to services, regulators might interventions. implement social tariff schemes to secure affordability of services for the poor. One common example is Though literature on WSS sector regulation in LMICs the “life line scheme,” implemented with varying holds off on providing a template for reform, it often success. Regulators could also provide targeted recommends a set of principles for effective regulation subsidies through direct transfers. that are commonly followed by better-performing Strengthening Regulation: The Way Forward regulatory frameworks: Any regulatory model must be fit for purpose and custom experiences where political entities who are bound and political economy. This requires regulators and ser- by a strong legal framework have successfully imple- vice providers to learn, adapt, and improve over time. require the following broader institutional reform considerations: a. Identify key reform drivers. These are

for Water Supply and Sanitation Service Delivery, and forms part of the Water Supply and Sanitation Global Solutions Group (WSS GSG) agenda. This work was financed by the World Bank's Global Water Security and Sanitation Partnership and the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO). This discussion paper was prepared by a team led by

PART I : WATER SUPPLY ENGINEERING Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1-1. General 1-2. Need to protect water supplies 1-3. Water supply schemes 1-4. Project drawings 1-5. Report of water supply scheme/project 1-6. Importance of water supply project 1-7. Layout of water supply project QUESTIONS 1 Chapter 2 QUANTITY OF WATER 2-1. Data to be collected 2-2 .

Regulation 5.3.18 Tamarind Pulp/Puree And Concentrate Regulation 5.3.19 Fruit Bar/ Toffee Regulation 5.3.20 Fruit/Vegetable, Cereal Flakes Regulation 5.3.21 Squashes, Crushes, Fruit Syrups/Fruit Sharbats and Barley Water Regulation 5.3.22 Ginger Cocktail Regulation 5.3.23 S

2. An overview of urban water supply in india 3. Governance and regulation 4. Key public sector programmes 5. Public private partnership (PPP) projects in urban water supply 6. Service delivery levels and benchmarks 7. Water quality 8. Water resourcing issues 9. Key challenges for urban poor 10. Reforms in urban water supply References

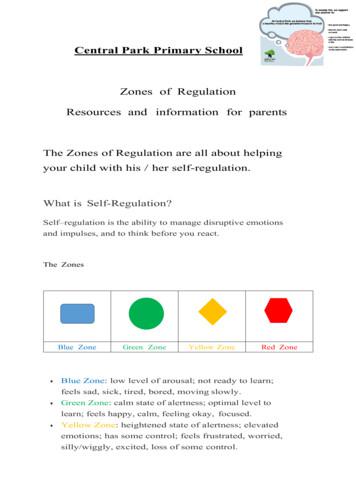

Zones of Regulation Resources and information for parents . The Zones of Regulation are all about helping your child with his / her self-regulation. What is Self-Regulation? Self–regulation is the ability to manage disruptive emotions and impulses, and

Regulation 6 Assessment of personal protective equipment 9 Regulation 7 Maintenance and replacement of personal protective equipment 10 Regulation 8 Accommodation for personal protective equipment 11 Regulation 9 Information, instruction and training 12 Regulation 10 Use of personal protective equipment 13 Regulation 11 Reporting loss or defect 14

The Rationale for Regulation and Antitrust Policies 3 Antitrust Regulation 4 The Changing Character of Antitrust Issues 4 Reasoning behind Antitrust Regulations 5 Economic Regulation 6 Development of Economic Regulation 6 Factors in Setting Rate Regulations 6 Health, Safety, and Environmental Regulation 8 Role of the Courts 9

Water Re-use. PRESENTATION TITLE / SUBTITLE / DATE 3. Water Scarcity. Lack of access to clean drinking water. New challenges call for new solutions Water Mapping: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Reclaim Water resources Water Fit for Purpose Water resources Tap Water Waste water Cow Water Rain water Others WIIX Mapping True Cost of Water

Turn "OFF" electrical supply to the water heater. FIGURE 1. 2. Open a nearby hot water faucet until the water is no longer hot. When the water has cooled, turn "OFF" the water supply to the water heater at the water shut-off valve or water meter. FIGURE 2. 3. Attach a hose to the water heater drain valve and put the other