LangMag July06 36 37.qxd (Page 1)

Professional DevelopmentScaffolding SuccessFive Principles for Succeeding with Adolescent English Learners:An Interview with Aída WalquiAída Walqui, director of the TeacherProfessional Development Program atWestEd, is the author with Leo van Lier,Professor of Educational Linguistics at theMonterey Institute of International Studies, ofa new book addressing the education ofEnglish learners in middle school and highschool. Based on sociocultural theory, sociolinguistics, and classroom research, thebook, Scaffolding the Academic Success ofAdolescent English Language Learners: APedagogy of Promise, takes readers insidesome of the classrooms where Walqui andWestEd’s Quality Teaching for EnglishLearners (QTEL) project have worked to instillfive principles into the instruction that supports English learners.24In the interview below, Walqui explains theimportance of instructional principles forteachers’ increased professional expertiseand impact on their students’ learning.Additionally, excerpts from the book outlinethe five QTEL principles and how educatorscan recognize them in practice.Q: In your new book, you discuss why itis important for teachers to have explicit principles that guide their teaching. What in yourown teaching led you to this conclusion?Walqui: The richest professional experience I’ve had, one I continue to reflect onand learn from, was my time as a teacher atAlisal High School in Salinas, California.Intuitively, it was my style to challenge students, which also meant supporting them tohttp://www.languagemagazine.comrise to my expectations. For the most part Ifelt successful. I could see my studentsgrowing intellectually, socially, and linguistically. At the same time, I often made mistakes.So, I became metacognitive about my ownteaching. For example, I reflected on the wayI conducted lessons, why I did not follow thebook in a sequential way, why I needed todesign specific activities, and how the students responded — badly or well — to specific episodes of my teaching. I also visitedfellow teachers to observe their teaching, tolearn. Sometimes I would observe two different teachers who were both excellent buttheir teaching looked quite different, and Iwondered about that. Sometimes I wouldobserve a lesson focused on superficial ideasFebruary 2010

Professional Developmentor a lesson where a student’s role was limitedto listening to the teacher or filling in worksheets. It was clear to me that these wereexamples of poor teaching. But what guidedmy ability to make decisions about the valueof those classes?I realized the importance of being explicitabout my theory of teaching and learning. Ifound that I could abstract principles fromconcrete instances of teaching to tease outguiding characteristics. By being explicit aboutwhat to me constituted accomplished teaching, I could talk about it with colleagues, elaborate on it, evaluate it, and continuously refineit. I came to see carefully elaborated principlesas the cornerstone of informed practice, andthe way we grow as teachers.Q: How did you arrive at the five principlesthat guide WestEd’s QTEL project? (See thebox on page 26 Principles and Goals forSucceeding with English Language Learners.)Walqui: In 2003, my teammates in theQTEL program and I started to work in NewYork City. Our main charge was to developthe expertise of district colleagues who wouldbe the professional developers and coachesof teachers who worked with EnglishLearners. We needed guidelines to help focuson what we considered the essentials ofteaching English Learners.Based on our experiences observing classes, we described what we knew about thecharacteristics of good teaching. We thensorted out specific descriptors and categorized them. For example, we agreed thatgood teaching engaged students in establishing connections between and across keyideas of the theme being learned; then wesorted out “connections,” “engagement,” and“key ideas.” We further sorted “connections”and “key ideas” together, into a category thatgrew and eventually became our principlerelated to “academic rigor.” We sorted “engagement” into a category that grew and becameour principle related to “quality interactions.” Inthis way, we arrived at five principles that wecould explicitly unpack. We also comparedthem to other principles available in the literature to see what kinds of organizers othereducators had used, what lenses they hadbrought to their work that we might be missing. In the process, we especially liked theFebruary 2010principles from the Productive Pedagogies inQueensland, Australia, and their concept ofrich tasks. “Tasks” became an important wayfor us to organize our ideas about our principle related to “quality curriculum.”Our principles have resulted in a public document about quality education that providesteachers with a clear focus for designing andenacting instruction; for collaborating with others; and for assessing, independently and jointly, the development of their expertise to workwith English Learners and all other students.In 2004, working in collaboration withOfelia García, who was then a professor atTeachers College, we designed an observational instrument based on the QTEL principles and their operationalization. The principles and the instrument point in the samedirection: It is a teacher’s job to take theimmense potential that students bring to theclassroom and transform it into reality by scaffolding students’ access to the high-challengetasks teachers invite them to engage in.Q: Is there one principle that you want tomake a special case for, one that might bethe key to working with English Learners?Walqui: The centerpiece of our work is theprinciple related to “quality interaction,”because it subsumes all that we believe isessential for learning. If a teacher can designactivities that help students interact aroundkey ideas — connecting them, critiquingthem, building on them, using them to solveproblems — then although the focus is on theinteraction, all other principles are equallyinvolved and students are constructing andgenerating new knowledge.Q: How do you hope readers will respondto the ideas you offer below and in yourbook?Walqui: I know sometimes teachers thinkthat theory is not relevant to them, that whatthey need to become better teachers is moreideas to improve their practice. However, Iagree with the psychologist Kurt Lewin:“There is nothing more practical than a goodtheory.” Theories help us describe and understand what we do, they can help us establishsolid principles and practices, and they giveus a sense of strength, focus, and direction.In accomplished teaching, theory and practiceare le One:Sustain Academic RigorThe fact that learners are learning Englishdoes not mean they are incapable of tacklingcomplex subject matter concepts in this newlanguage. Simply put: Do not dumb down theacademic challenge for English languagelearners. Instead, support them so that theycan access and engage with high-level subject matter content.The first goal in sustaining academic rigoris to promote deep disciplinary knowledge:What are the key ideas in a subject area, thedeep connections between and across factsrelated to those core ideas, the basic conceptual structure of the discipline, the processesvalued in the field, and the preferred ways ofexpressing them? This kind of search for integration and connection may have beenuncommon in teachers’ own training andpractice (Elmore, 1996), so it requires teachers’ critical reflection on their own experiencesas learners, to reconceptualize disciplinaryknowledge, to rethink how to support students’ understanding of core disciplinaryideas and processes, and to socialize learnersinto the discipline (Shulman, 1987). Teacherssustain academic rigor by keeping the focusclear: main themes appear time and again, asleitmotifs, and each time they reappear, students’ understanding should deepen.Two other goals for sustaining academicrigor — to engage students in generative disciplinary concepts and skills and to engage students in generative cognitive skills (higher-orderthinking) — can be illustrated with a simpleexample. English language learners need to beinvited to combine ideas, to synthesize, tocompare and contrast, and so forth. It’s truethat, in many cases, they may not have the language to do so on their own, but if providedwith useful expressions and carefully guidedchoices, they can begin to apprentice into thelanguage and make sense of the concepts.This should happen even in the beginning ESLclass. If students can say, “This is a square,”and, “That is a triangle,” they can also behelped to understand and say, “This figure is asquare because it has four sides, while that figure is a triangle because it has three sides.”The idea that teachers can focus theirinstruction on central ideas and deepen stu-25

Professional DevelopmentPrinciples and Goals for Succeeding with English Language LearnersPrinciplesGoalsSustain Academic RigorPromote deep disciplinary knowledgeEngage students in generative disciplinary conceptsand skillsEngage students in generative cognitive skills(higher-order thinking)Hold High ExpectationsEngage students in tasks that provide high challengeand high supportEngage students (and teachers) in the developmentof their own expertiseMake criteria for quality work clear to allEngage Students in QualityInteractionsEngage students in sustained interactions withteacher and peersFocus interactions on the construction of knowledgeSustain a Language FocusPromote language learning in meaningful contextsPromote disciplinary language useAmplify rather than simplify communicationsAddress specific language issues judiciouslyDevelop Quality CurriculumStructure opportunities to scaffold learning,incorporating the goals above 2010 WestEddents’ understanding over time also dispenses with the common complaint that it is notpossible to teach everything in the curriculum. The point is, no one should try. It’s notgood pedagogy. If students understand thecentral concepts that make up the core of adiscipline and the main ways these conceptsare interrelated, they will then be able toanchor and build other understandings; theywill generate new knowledge.Principle Two:Hold High ExpectationsIn the classic study of the “Pygmalion effect”(Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1966), teacherswere given a list of students whose IQ testssupposedly showed they were about to enteran intellectual “spurt;” teachers paid thesemore “promising” students more attention,and the students performed better thanexpected. However, what the teachers didnot know was that the students had beenassigned to the list on a purely random basis.In other words, the differences in the students’ performance were based purely onthe teacher’s treatment, which, in turn, wasbased on the teacher’s expectations as26derived from the fictitious list. This study, andothers like it, should serve as a powerfulreminder of the influence of expectations onperformance, in both the long and shortterm. If we (as individual teachers, as aschool system, or as a nation) treat Englishlanguage learners as incapable of succeeding academically, or, worse, if we regardthem as somehow deficient (lazy, unintelligent, or whatever), then these students mustfight against vastly increased odds.However, it won’t be enough to swap lowexpectations for high expectations if we don’talso provide the high levels of support thatwe know English language learners will need.This is distinct from differentiating instructionin ways that attempt to address students’diverse needs by creating separate lessonplans for English language learners, nativespeakers of English, struggling readers, andso on. The QTEL approach is to differentiatewithin the same complex activities. The goalis to engage all students in the same tasks,designed with the same objectives, to provide high challenge and high support regardless of students’ differences. For example, ajigsaw project can be structured to involvehttp://www.languagemagazine.comsmall groups in addressing the same topic(brain function, say) with the same questions,but the subtopics (different cases of braininjury) and level of the reading assignmentscan be differentiated. What is not differentiated is the task itself or the core concepts. Insuch a jigsaw project, every student is carefully assigned to two different kinds ofgroups: an “expert” group and a “base”group. First, in expert groups, students worktogether to become expert about their particular subtopic. Then, in base groups, studentsfrom different expert groups meet toexchange and compare what they learned —about the same core concept.In the example above, the structure of theactivity clearly communicates that all students are considered capable of learning thesame ideas and that all students are expected to grow intellectually. (Conversely, givingstudents different tasks that do not appear tobe of equal importance communicates thatthe teacher may not believe all members ofthe class community can achieve.)It almost goes without saying that if weare going to have high expectations for students, they need to have clear understandingof what those expectations are and the criteria by which they will be assessed. Theexplicitness of these criteria enables studentsto self-monitor and correct and, thus, toimprove their own performances. Rubrics areone straightforward way to communicateexpectations. Additionally, rubrics supportstudents in developing the importantmetacognitive skill of self-assessment.Principle Three:Engage English Language Learnersin Quality InteractionsHere is the principle that QTEL has found tobe the key to all work with English learners.By our definition, quality interactions focus onthe sustained joint construction of knowledge. In some instances the interactions arebetween the teacher and learner; many othertimes, the teacher designs and monitorsinteractions that take place among students.We want all students, and English learners inparticular, to construct new knowledge byengaging in interactions that pursue understanding, enhance it, problematize1 centralideas, propose counter arguments, debate,and reach some sort of conclusion.Consider, for example, the interactionsincluded here on this page from a highFebruary 2010

Professional Developmentschool ESL classroom. Students are beginning a linguistics unit and have investigatedseveral questions about language, includingwhether animals have language.Throughout this discussion, students’ sustained interactions build toward coherenceand jointly constructed understanding. Insummarizing the discussion, the teacheralerts students to the academic sophistication of their work together and provides away for them to think about the origins oftheir arguments in the fields of linguistics andzoology. For an observer of this classroom,the interactions between teacher and students and among students clearly meet thedefinition of “high quality.”Principle Four:Sustain a Language FocusTeaching a class with English LanguageLearners means that every lesson, regardlessof the subject area, becomes a language lesson to some extent. The teacher has to takeinto account that English language learnersnot only need to cope with the cognitiveaspects of a lesson, but also will strugglewith language issues — with grammar andvocabulary, listening comprehension, takingnotes, and so on. Even for English LanguageLearners who have a good level of oral proficiency in everyday communication and conversation, the academic language of disciplinary discourse almost always presents problems.However, a focus on language does nothave to be in the form of grammar rules ormemorization of vocabulary. Nor does itrequire simplification of the often-complexlanguage of academic disciplines. The bestapproach to sustaining a language focus insubject matter classes incorporates threegoals: to focus on language issues in meaningful contexts and activities, to amplify students’ access to the academic language theyneed to learn, and to focus judiciously onexplicit language issues.Meaningful contexts begin at the genrelevel. All students should be helped todeconstruct disciplinary genres: What is thepurpose of this text? What do I know aboutthe structure of this type of text? What tendsto come first, follow, and then conclude it?What patterns of academic language use aretypical (e.g., describing, explaining, justifying)? What kind of language is typical (e.g.,connectors, preferred verb tenses, nominalFebruary 2010Student 1: I found from my research that animal communication is not a language.Animal communication is different from the human communication because, in case ofdolphins, they communicate through ultrasonic pulses that cannot be heard by thehuman ear.Student 2: She says that animal communication is not a language. It IS a language,that’s what I think. Because they communicate with each other.Student 1: But they don’t think.Student 2: A characteristic in the language, you can have words, sounds, and everything.Student 1: But they don’t have words. They don’t say “mama.”Student 2: In animal language are some of the characteristics that you said are there,so.it is a language.Teacher:Julio is arguing very strongly that animal communication is a form of, islanguage. Lavinia’s saying it’s not. What do you think would be a way to help themresolve that argument in their writing?Student 1: Similarities in the.I mean they have sound, both of them. Because we havesound and animals have sound, but they don’t have lexis, they don’t have grammar.Student 3: I hear people say that animals they understand everything, but only thingthey don’t do is they don’t speak. So, that’s the only thing (inaudible) they understandlike humans do.Student 4: Look, if you want to say, “Excuse me” (makes sound of clearing his throatto demonstrate that sounds can replace words to communicate), “huh, huh.”Student 1: They don’t say, “Excuse me.”Student 4: Same thing, sound.Teacher:Hold on, hold on. Angela has something.Student 5: What I want to say, because they don’t talk, but they communicate bydoing signs, so they do not need to speak to communicate to others. So I think that’s alanguage.Teacher:A lot is going to depend on how you define language, okay? You candefine it in such a way as to exclude what animals do; you can define it in a very broadway, as a system of communication that includes everything. You are going to find linguists and zoologists who disagree. And if you get interested, I can give you somereadings that were in the journal Science last year, people arguing back and forth, calling one another names because they disagreed on this issue.(DeFazio and Walqui, 2001)izations)? Formulaic expressions, too, can beseen as a particular aspect of genre, as specific ways to conduct academic discussions,report laboratory findings, or present an historical claim, for example.Teaching with a language focus alsomeans recognizing concepts and terms thatwill need to be amplified for English learners.Even more important is recognizing andamplifying learners’ access to concepts, withlanguage as the touchstone. “Short” circuits,for example, will need to be read about, discussed, drawn, discussed, constructed, discussed, and so forth.It is not always the teacher who focuseson language in subject matter classes, ofcourse. Learners will often take the initiativehttp://www.languagemagazine.comas they engage with challenging texts andactivities. When they encounter particularproblems that need to be resolved, they willnaturally focus on language and attempt tofigure out how to assign meaning and makesense of the subject matter. The teacher —and other learners — need to understandthat learners can often find the solution totheir linguistic problems by discussing themwith each other or by targeted guidance fromtheir teacher (see, for example, Donato,1994; Brooks, Donato, and McGlone, 1997;and Swain

Principle Two: Hold High Expectations . to pro-vide high challenge and high support regard-less of students’ differences. For example, a jigsaw project can be structured to involve small groups in addressing the

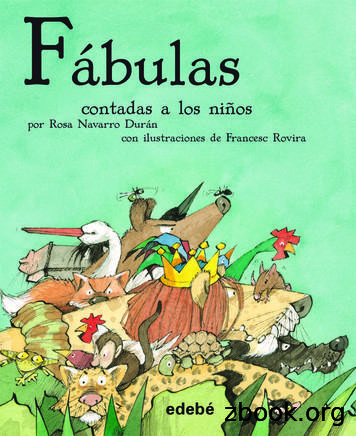

fabulas.qxd:Leyendas_Becquer_CAT.qxd 26/4/10 15:22 Página 14. 15 No hay que imitar a la cigarra ya que siempre llega el in-vierno en la vida y nos falta lo que despreciamos otro tiempo. Pero tampoco se debe ser tan poco caritativo como la hormiga, porque compartir las cosas da mucho gusto.

46672ffirs.qxd:Naked Conversations 3/26/08 1:36 AM Page iv. Dedicated to our families, friends, and the bloggers we have yet to meet. 46672ffirs.qxd:Naked Conversations 3/26/08 1:36 AM Page v. About the Authors Darren Rowse is t

LAURA NAPRAN has a Ph.D. in medieval history from University of Cambridge (Pembroke) and is an independent scholar. . The manuscripts xxviii Editions and translations xxx . Places xxxviii CHRONICLE OF HAINAUT 1 Bibliography 183 Index 199 COH-Prelims.qxd 11/15/04 5:56 PM Page v. COH-Prelims.qxd 11/15/04 5:56 PM Page vi. For Norm Socha COH .

ADVANCED ENGINEERING MATHEMATICS By ERWIN KREYSZIG 9TH EDITION This is Downloaded From www.mechanical.tk Visit www.mechanical.tk For More Solution Manuals Hand Books And Much Much More. INSTRUCTOR’S MANUAL FOR ADVANCED ENGINEERING MATHEMATICS imfm.qxd 9/15/05 12:06 PM Page i. imfm.qxd 9/15/05 12:06 PM Page ii. INSTRUCTOR’S MANUAL FOR ADVANCED ENGINEERING MATHEMATICS NINTH EDITION ERWIN .

processes that have marked the human occupation and transformation of the landscape. (Joanna Dean’s chapter, which follows this one, reinforces this point by looking at urban forests in Toronto.) ch12.qxd 12/28/07 4:08 PM Page 214. By examining stages in the creation of water networks and green spaces in Montreal from the 1850s to the 1910s, we will see changes in how natural elements were .

USER GUIDE TOASTER PAGE 2 840141600 ENv01.qxd 3/31/06 2:06 PM Page 1. 2 Dear Toaster Owner, Congratulations on your purchase. The Hamilton Beach . Assistance and Service 840141600 ENv01.qxd 3/31/06 2:06 PM Page 5. 6 Parts and Features 1. Food Slots with Guides 2.

MICROECONOMICS FIFTH EDITION DAVID A. BESANKO Northwestern University, Kellogg School of Management RONALD R. BRAEUTIGAM Northwestern University, Department of Economics with Contributions from Michael J. Gibbs The University of Chicago, Booth School of Business FM.qxd 10/5/13 1:36 AM Page i

paper no.1( 2 cm x 5 cm x 0.3 mm ) and allowed to dry sera samples at 1: 500 dilution and their corresponding at room temperature away from direct sun light after filter paper extracts at two-fold serial dilutions ranging that stored in screw-capped air tight vessels at – 200C from 1: 2 up to 1: 256.