CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 305 About Moral Issues .

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 305Thinking CriticallyAbout Moral Issues9Justify moraljudgmentsMake moralitya priorityPromotehappinessThe Thinker’s Guide toMoral Decision-MakingConsider theethic of justiceDiscover the“Natural Law”YourmoralcompassConsider theethic of careChoose to bea moral personDevelop aninformed intuitionAccept responsibility Houghton Mifflin305

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 306306Chapter 9Thinking Critically About Moral IssuesThe abilities that you develop as a critical thinker are designed to help you thinkyour way through all of life’s situations. One of the most challenging and complex of life’s areas is the realm of moral issues and decisions. Every day of your lifeyou make moral choices, decisions that reflect your own internal moral compass.Often we are not aware of the deeper moral values that drive our choices, and wemay even be oblivious to the fact that the choices we are making have a moral component. For example, consider the following situations: You consider purchasing a research paper from an online service, and youplan to customize and submit the paper as your own. As part of a mandatory biology course you are taking, you are required to dissect a fetal pig, something which you find morally offensive. A friend of yours has clearly had too much to drink at a party, yet he’s insisting that he feels sober enough to drive home. The romantic partner of a friend of yours begins flirting with you. You find yourself in the middle of a conversation with people you admire inwhich mean-spirited things are being said about a friend of yours. Although you had plans to go away for the weekend, a friend of yours isextremely depressed and you’re concerned about leaving her alone. A good friend asks you to provide some “hints” about an upcoming exam thatyou have already taken. You and several others were involved in a major mistake at work, and yoursupervisor asks you to name the people responsible. A homeless woman asks you for a donation, but you’re not convinced that shewill use your money constructively. Although you have a lot of studying to do, you had promised to participate ina charity walk-a-thon.These and countless other situations like them are an integral part of the choicesthat we face each day as we shape our lives and create ourselves. In each case, thechoices involved share the following characteristics: The choices involve your treatment of other people (or animals). There may not be one obvious “right” or “wrong” answer, and the dilemmacan be discussed and debated. There are likely to be both positive and/or negative consequences to yourselfor others, depending on the choices that you make. Your choices are likely to be guided by values to which you are committed andthat reflect a moral reasoning process that leads to your decisions. The choices involve the concept of moral responsibility.Critical thinking plays a uniquely central role in helping us to develop enlightened values, use informed moral reasoning, and make well-supported ethical Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 307What Is Ethics?307conclusions. Most areas of human study are devoted to describing the world andhow people behave, the way things are. Ethics and morality are concerned withhelping people evaluate how the world ought to be and what courses of actionpeople should take; to do this well, we need to fully apply our critical-thinking abilities. Thinking critically about moral issues will provide you with the opportunityto refine and enrich your own moral compass, so that you will be better equippedto successfully deal with the moral dilemmas that we all encounter in the course ofliving. As the Greek philosopher Aristotle observed:The ultimate purpose in studying ethics is not as it is in other inquiries, the attainment of theoretical knowledge; we are not conducting this inquiry in order toknow what virtue is, but in order to become good, else there would be no advantage in studying it.This was precisely how Socrates envisioned his central mission in life, to remindpeople of the moral imperative to attend to their souls and create upstanding character and enlightened values within themselves:For I do nothing but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, not to takethought for your persons or your properties, but first and chiefly to care about thegreatest improvement of your soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money,but that from virtue comes money and every other good of man, public as well asprivate. This is my teaching.What Is Ethics?Ethics and morals are terms that refer to the principles that govern our relationshipswith other people: the ways we ought to behave, the rules and standards that weshould employ in the choices we make. The ethical and moral concepts that we useto evaluate these behaviors include right and wrong, good and bad, just and unjust,fair and unfair, responsible and irresponsible.The study of ethics is derived from the ancient Greek word ethos, which refersto moral purpose or character—as in “a person of upstanding character.” Ethos isalso associated with the idea of “cultural customs or habits.” In addition, the etymology of the word moral can be traced back to the Latin word moralis, which alsomeans “custom.” Thus, the origins of these key concepts reflect both the private andthe public nature of the moral life: we strive to become morally enlightened people,but we do so within the social context of cultural customs.ethical, moral of or concerned with the judgment of the goodness or badness ofhuman action and characterEthical and moral are essentially equivalent terms that can be used interchangeably, though there may be shadings in meaning that influence which term is used.For example, we generally speak about medical or business “ethics” rather than Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 308308Chapter 9Thinking Critically About Moral Issues“morality,” though there is not a significant difference in meaning. Value is the general term we use to characterize anything that possesses intrinsic worth, that weprize, esteem, and regard highly, based on clearly defined standards. Thus, you mayvalue your devoted pet, your favorite jacket, and a cherished friendship, each basedon different standards that establish and define their worth to you. One of the mostimportant value domains includes your moral values, those personal qualities andrules of conduct that distinguish a person (and group of people) of upstandingcharacter. Moral values are reflected in such questions as Who is a “good person” and what is a “good action”? What can we do to promote the happiness and well-being of others? What moral obligations do we have toward other people? When should we be held morally responsible? How do we determine which choice in a moral situation is right or wrong, justor unjust?Although thinking critically about moral values certainly involves the moralcustoms and practices of various cultures, its true mandate goes beyond simpledescription to analyzing and evaluating the justification and logic of these moralbeliefs. Are there universal values or principles that apply to all individuals in allcultures? If so, on what basis are these values or principles grounded? Are someethical customs and practices more enlightened than others? If so, what are thereasons or principles upon which we can make these evaluations? Is there a“good life” to which all humans should aspire? If so, what are the elements ofsuch a life, and on what foundation is such an ideal established? These are questions that we will be considering in this chapter, but they are questions of suchcomplexity that you will likely be engaged in thinking about them throughoutyour life.Who is a moral person? In the same way that you were able to define the key qualities of a critical thinker, you can describe the essential qualities of a moral person.Thinking Activity 9.1WHO IS A MORAL PERSON?Think of someone you know whom you consider to be a person of outstandingmoral character. This person doesn’t have to be perfect—he or she doubtless hasflaws. Nevertheless, this is a person you admire, someone you would like to emulate. After fixing this person in your mind, write down this person’s qualities that,in your mind, qualify him or her as a morally upright individual. For each quality,try to think of an example of when the person displayed it. For example:Moral Courage: Edward is a person I know who possesses great moral courage.He is always willing to do what he believes to be the right thing, even if his pointof view is unpopular with the other people involved. Although he may endure Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 309What Is Ethics?309criticism for taking a principled stand, he never compromises and instead calmlyexplains his point of view with compelling reasons and penetrating questions.If you have an opportunity, ask some people you know to describe their idea of amoral person, and compare their responses to your own.For millennia, philosophers and religious thinkers have endeavored to developethical systems to guide our conduct. But most people in our culture today have notbeen exposed to these teachings in depth. They have not challenged themselves tothink deeply about ethical concepts, nor have they been guided to develop coherent,well-grounded ethical systems of their own. In many cases people attempt to navigate their passage through the turbulent and treacherous waters of contemporary lifewithout an accurate moral compass, relying instead on a tangled mélange of childhood teachings, popular wisdom, and unreliable intuitions. These homegrown andunreflective ethical systems are simply not up to the task of sorting out the moralcomplexities in our bewildering and fast-paced world; thus, they end up contributing to the moral crisis described in the following passage by the writer M. Scott Peck:A century ago, the greatest dangers we faced arose from agents outside ourselves:microbes, flood and famine, wolves in the forest at night. Today the greatestdangers—war, pollution, starvation—have their source in our own motives and sentiments: greed and hostility, carelessness and arrogance, narcissism and nationalism.The study of values might once have been a matter of primarily individual concernand deliberation as to how best to lead the “good life.” Today it is a matter of collective human survival. If we identify the study of values as a branch of philosophy, thenthe time has arrived for all women and men to become philosophers—or else.How does one become a “philosopher of values”? By thinking deeply and clearlyabout these profound moral issues, studying the efforts of great thinkers through theages who have wrestled with these timeless questions, discussing these concepts withothers in a disciplined and open-minded way, and constructing a coherent ethicalapproach that is grounded on the bedrock of sound reasons and commitment to thetruth. In other words, you become a philosopher by expanding your role as a critical thinker and extending your sophisticated thinking abilities to the domain ofmoral experience. This may be your most important personal quest. As Socratesemphasized, your values constitute the core of who you are. If you are to live a lifeof purpose, it is essential that you develop an enlightened code of ethics to guide you.Thinking Activity 9.2WHAT ARE MY MORAL VALUES?You have many values—the guiding principles that you consider to be mostimportant—that you have acquired over the course of your life. Your values dealwith every aspect of your experience. The following questions are designed to elicit Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 310310Chapter 9Thinking Critically About Moral Issuessome of your values. Think carefully about each of the questions, and record yourresponses along with the reasons you have adopted that value. In addition, describeseveral of your moral values that are not addressed in these questions. A sample student response is included below. Do we have a moral responsibility toward less fortunate people? Is it wrong to divulge a secret that someone has confided in you? Should we eat meat? Should we wear animal skins? Should we try to keep people alive at all costs, no matter what their physical ormental condition? Is it wrong to kill someone in self-defense? Should people be given equal opportunities, regardless of race, religion, or gender? Is it wrong to ridicule someone, even if you believe it’s in good fun? Should you “bend the rules” to advance your career? Is it all right to manipulate people into doing what you want if you believe it’sfor their own good? Is there anything wrong with pornography? Should we always try to take other people’s needs into consideration when weact, or should we first make sure that our own needs are taken care of? Should we experiment with animals to improve the quality of our lives?I do believe that we have a moral obligation to those less fortunate than us. Whycan a homeless person evoke feelings of compassion in one person and complete disgustin another? Over time, observation, experience, and intuition have formed the cornerstones of my beliefs, morally and intellectually. As a result, compassion and respect forothers are moral values that have come to characterize my responses in my dealingswith others. As a volunteer in an international relief program in Dehra Dun, India, I wasassigned to various hospitals and clinics through different regions of the country. InDelhi, I and the other volunteers were overwhelmed by the immense poverty—thousandsof people, poor and deformed, lined the streets—homeless, hungry, and desperate.We learned that over 300 million people in India live in poverty. Compassion, asBuddhists describe it, is the spontaneous reaction of an open heart. Compassion forall sentient beings, acknowledging the suffering and difficulties in the world aroundus, connects us not only with others but with ourselves.After you have completed this activity, examine your responses as a whole. Dothey express a general, coherent, well-supported value system, or do they seemmore like an unrelated collection of beliefs of varying degrees of clarity? Thisactivity is a valuable investment of your time because you are creating a recordof beliefs that you can return to and refine as you deepen your understanding ofmoral values. Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 311Your Moral Compass311Your Moral CompassThe purpose of the informal self-evaluation in Thinking Activity 9.2 is to illuminateyour current moral code and initiate the process of critical reflection. Which ofyour moral values are clearly articulated and well grounded? Which are ill definedand tenuously rooted? Do your values form a coherent whole, consistent with oneanother, or do you detect fragmentation and inconsistency? Obviously, constructing a well-reasoned and clearly defined moral code is a challenging journey. But ifwe make a committed effort to think critically about the central moral questions,we can make significant progress toward this goal.Your responses to the questions in Thinking Activity 9.2 reveal your current values. Where did these values come from? Parents, teachers, religious leaders, andother authority figures have sought to inculcate values in your thinking, but friends,acquaintances, and colleagues do as well. And in many cases they have undoubtedlybeen successful. Although much of your values education was likely the result ofthoughtful teaching and serious discussions, in many other instances people may Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 312312Chapter 9Thinking Critically about Moral Issueshave bullied, bribed, threatened, and manipulated you into accepting their way ofthinking. It’s no wonder that our value systems typically evolve into a confusingpatchwork of conflicting beliefs.In examining your values, you probably also discovered that, although you hada great deal of confidence in some of them (“I feel very strongly that animals shouldnever be experimented on in ways that cause them pain because they are sentientcreatures just like ourselves”), you felt less secure about other values (“I feel it’s usually wrong to manipulate people, although I often try to influence their attitudesand behavior—I’m not sure of the difference”). These differences in confidence arelikely related to how carefully you have examined and analyzed your values. Forexample, you may have been brought up in a family or religion with firmly fixedvalues that you have adopted but never really scrutinized or evaluated, wearingthese values like a borrowed overcoat. When questioned, you might be at a loss toexplain exactly why you believe what you do, other than to say, “This is what I wastaught.” In contrast, you may have other values that you consciously developed, theproduct of thoughtful reflection and the crucible of experience. For example, doingvolunteer work with a disadvantaged group of people may have led to the conviction that “I believe we have a profound obligation to contribute to the welfare ofpeople less fortunate than ourselves.” Houghton Mifflin

CH09.qxd 11/3/07 5:15 AM Page 313Your Moral Compass313In short, most people’s values are not systems at all: they are typically a collectionof general principles (“Do unto others . . .”), practical conclusions (“Stealing iswrong because you might get caught”), and emotional pronouncements(“Euthanasia is wrong because it seems heartless”). This hodgepodge of values mayreflect the serendipitous way they were acquired over the course of your life, andthese values likely comprise the current moral compass that you use to guide yourdecisions in moral situations, even though you may not be consciously aware of it.Your challenge is to create a more refined and accurate compass, an enlightened system of values that you can use to confidently guide your moral decisions.One research study that analyzed the moral compasses that young people use toguide their decision-making in moral situations asked interviewees, “If you wereunsure of what was right or wrong in a particular situation, how would you decidewhat to do?” (Think about how you would respond to this question.) According tothe researcher, here’s how the students responded: I would do what is best for everyone involved: 23 percent. I would follow the advice of an authority, such as a parent or teacher: 20 percent. I would do whatever made me happy: 18 percent. I would do what God or the Scriptures say is right: 16 percent. I would do whatever would improve my own situation: 10 percent. I do not know what I would do: 9 percent. I would follow my conscience: 3 percent.Each of these guiding principles represents a different moral theory that describesthe way people reason and make decisions about moral issues. However, moralvalues not only describe the way people behave; they also suggest that this is the waypeople ought to behave. For example, if I say, “Abusing children is morally wrong,”I am not simply describing what I believe; I am also suggesting that abusing childrenis morally wrong for everyone. Let’s briefly examine the moral theories representedby each of the responses just listed.I Would Follow My ConscienceWe could describe this as a psychological theory of morality because it holds thatwe should determine right and wrong based on our psychological moral sense. Ourconscience is that part of our mind formed by internalizing the moral values wewere raised with, generally from our parents but from other authority figures andpeers as well. If that moral upbringing has been intelligent, empathic, and fairminded, then our conscience can serve as a fairly sound moral compass to determine right and wrong. The problem with following our conscience occurs when themoral values we have internalized are not intelligent, empathic, or fair-minded. For

flaws. Nevertheless, this is a person you admire, someone you would like to emu-late. After fixing this person in your mind, write down this person’s qualities that, in your mind, qualify him or her as a morally upright individual. For each quality, try to think of an example of when the person displayed it. For example:

taining that metric after a specific period of time. Since the IWC ISSO had Establishing a Metrics Management System 197 1It is assumed each function costs time, money, and use of equipment to perform. Ch09.qxd 6/7/03 4:14 PM Page 197

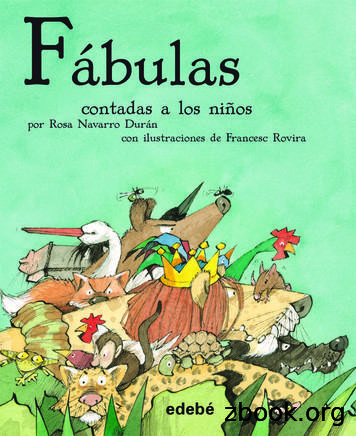

fabulas.qxd:Leyendas_Becquer_CAT.qxd 26/4/10 15:22 Página 14. 15 No hay que imitar a la cigarra ya que siempre llega el in-vierno en la vida y nos falta lo que despreciamos otro tiempo. Pero tampoco se debe ser tan poco caritativo como la hormiga, porque compartir las cosas da mucho gusto.

46672ffirs.qxd:Naked Conversations 3/26/08 1:36 AM Page iv. Dedicated to our families, friends, and the bloggers we have yet to meet. 46672ffirs.qxd:Naked Conversations 3/26/08 1:36 AM Page v. About the Authors Darren Rowse is t

LAURA NAPRAN has a Ph.D. in medieval history from University of Cambridge (Pembroke) and is an independent scholar. . The manuscripts xxviii Editions and translations xxx . Places xxxviii CHRONICLE OF HAINAUT 1 Bibliography 183 Index 199 COH-Prelims.qxd 11/15/04 5:56 PM Page v. COH-Prelims.qxd 11/15/04 5:56 PM Page vi. For Norm Socha COH .

Note that the sale manager’s proposed accounting is an example of “cookie jar” reserves, as discussed in Chapter 4. By writing the inventory down to an unsupported low value, the company can report higher gross profit and net income in subsequent periods when the inventory is sold.

chapter, organize your notes under the appropriate tabs. Chapter 9 Forces influence the motion and properties of fluids. MHR 333 Effects on fluids of Force Pressure Heat NL8 U2 CH09.indd 333 11/5/08 4:04:36 PM

Risk of Orthostatic Intolerance During Re-exposure to Gravity 9-4 I. PRD Risk Title: Risk of Orthostatic Intolerance During Re-Exposure to Gravity Description: Postflight orthostatic intolerance, the inability to maintain blood pressure while in an upright position, is an establish

Python Programming, 2/e 27 . The University of Western Australia Comparing Algorithms ! To determine how many items are examined in a list of size n, we need to solve for i, or . ! Binary search is an example of a log time algorithm – the amount of time it takes to solve one of these problems grows as the log of the problem size. Python Programming, 2/e 28 n 2i in log 2. The University of .