ACADEMIC ENTREPRENEURSHIP Bayh Dole Versus The Professor’s .

ACADEMIC ENTREPRENEURSHIPBayh‐DoleversusThe Professor’s PrivilegeThomas Åstebro, HEC Paris, KULeuvenSerguey Braguinsky, U MarylandPontus Braunerhjelm, KTH Royal Institute of TechnologyAnders Broström, KTH Royal Institute of Technology

What is the current thinking on university spin‐offs?Faculty should do more spin‐offsUniversities should spin off more start‐upsPolicies have been created to accomplish these goals:– Changes to laws to allow universities to take ownership and controlrights of academics’ IP Bayh‐Dole in U.S., copied by Denmark, Norway, Finland, Germany, Japan,China, and Belgium– Creation of TLOs to manage IP and stimulate spin‐offs– University funding of start‐ups– Academics (particularly in STEM fields) encouraged to create more spin‐offs– Spin‐off counts suggested to join bibliometric measures and externalfunding as criteria for evaluations of university performanceStill, university spin‐offs are rather few and far between

Swedish Political Context Professor’s Privilege in place since 1949– Professor own 100% of I.P.– Professor retain all control rights Politicians– Are concerned about the so called Swedish/European paradox– Have enviously observed “enormous success” of the post‐BDAcommercialization of research in the U.S.– Have twice debated in parliament whether to scrap the P.P. in favourof BDA legislation– Are aware that neighbours Denmark, Norway, Finland and Germanyhave converted to BDA– Fear that University Chancellors and Rectors, because universities bydefault have no stake in IPR, do not sufficiently strong promoteacademic entrepreneurship– Again consider repealing the P.P.

Recent time‐series evidenceChanging from Professor’s Privilege to Bayh‐Dolelegislation has– decreased academic patenting– decreased start‐ups– decreased university‐industry collaborationsignificantly in Denmark, Norway and Germany Czarnitzki et al., 2015; 2016; Hvide and Jones, 2015;Valentin and Lund‐Jensen, 2007

Do we have sufficient evidence? Are these studies assessing particular BDA implementationsor providing fundamental evidence on the effect of switchingIPR regimes? Are these studies capturing initial problems of institutionalimmaturity, while positive effects take more time tomaterialize?quality of coaching and support * university/TTO greed * intertia in achieving cultural shifts in academia

How can we further improve ourunderstanding of BDA vs PP ? We could wait for a switch in a country maintaining the PP but few remain, and even if one occurs we would have to waitseveral years to get our hands on appropriate data We could wait for longer time series which allow BDE institutions tomature but in the meantime, parallell development obscures our before‐after comparission We could also find a mature PP environment and compare it to amature BDA environment

Objective To compare U.S. vs Sweden on– The rate of STEM academic entrepreneurship– The earnings from commercialization One of the main differences: IPR regime. Cash‐flow rights and controlright are very different.Bayh‐Dole (42%) vs Professor’s Privilege (100%)– Expect higher absolute rate of academic entrepreneurship in the U.S.driven by difference in the general institutions of entrepreneurship– Expect higher relative rate of academic entrepreneurship in Swedendriven by PP / BDA differences– No strong prior expectation on U.S./Sweden differences in returns toentrepreneurshipBDA expected to trim the tail of entrepreneurship quality, but mayalso – depending on TTO incentives and quality – stimulate over‐entry

Why study the private returns toentrepreneurship? Making money is an important motivator for employmentchoices A relevant proxy for venture performance– allows us to pick up signs of over‐entry– has bearing on a discussion of the magnitude of social returns If the private returns to entrepreneurship are negative– we need theory going beyond income maximisation to explaintheir behavior– one might ask for policies to discourage such wasteful activities– but if social returns are clearly positive there is an argument forsubsidizing the expected losses of the agents (see Mansfield etal., 1977) If the returns are positive they need no subsidies

U.S. – Sweden InstitutionsMeasureIP regimeU.S.SwedenBayh-Dole30% ownership of IPProfessor’s Privilege100% ownership of IPTaxes/GDP (effective)25%45%University-industry collaborationHighHighLarge, public & private, largevarietySmall, public, little varietyDeregulatedComing down from heavyregulation35%-40%10%-15%Highest in world, skewModest, with wage compression6%5-7 %University SystemLabor MarketLabor turnoverAcademic EarningsPatenting / academic

General Methodology Lots of things vary between Sweden and the U.S. We try to difference those out Entrepreneurship rates: Difference‐in‐Difference– Rate of entrepreneurship by academics (a)– Rate of entrepreneurship by non‐academics with similar Ph.D.’s (b)– Difference between (a/b) between U.S. and Sweden Earnings: Triple s by academics (a)Earnings by same academics after becoming entrepreneurs (b)Earnings by non‐academics with similar Ph.D.’s (c)Earnings by same non‐academics after becoming entrepreneurs (d)Difference between (a/b) – (c/d) between U.S. and Sweden

Data Statistics Sweden Register data All individuals with a Ph.D. in STEM (Medicine, Natural Science or Engineering)who during 1999‐2008 were employed at a Swedish university. Removed all above60 years of age.– 278 individuals leaving a Swedish university to become full‐time entrepreneurs. Add those who left academia to work full‐time for a new small company ( 10employees) founded in the year they left academia– Add 200 individuals– 25% of these were verified owners of the firms they worked in 2,720 year‐observations U.S. SESTAT survey data 322 similarly defined STEM individuals making the transition1,045 year‐observations for 1993, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2003, and 2006 Differences across countries have to be done with t‐tests

Variables Annual income from the Swedish tax register. Surveyself‐reported income from U.S. SESTAT– Wages, business earnings Employed at university, or employed by themselves /own a business and work full‐time there Socio‐demographic background; field of Ph.D., foreignborn, gender, marital status, years since Ph.D., years atlast employer, tenure‐track position University quality: [R&D intensity (R&D/employee) orNRC score]

RESULTS:Entry into EntrepreneurshipMeasureBi-annual non-acadentrepreneurshiprateBi-annual academicentrepreneurshiprateRelative entry rateU.S.Sweden4.0%2.5%0.9%1.1%25%44%

Linear Probability of EntrepreneurshipPanel ineering.009***(.003)Foreign ars Experience.002***(.000).003**(.002)Years last employer-.002***(.000)-.005**(.002)Tenure track 002)University quality-.003***(.001).003**(.001)No observations29,65268,746**significant at 1% level, * significant at 5% level.

PRELIMINARY RESULTSPrivate Returns Estimation Difference individual‐fixed estimator on sample who becomeentrepreneursyit Eit ( X it ) i t itEYXθτ 1 for years when entrepreneur, 0 elselog(earnings)covariatesindividual‐fixed effectstime‐fixed effectsEstimate the effect of covariates on the difference in income betweenentrepreneurship and employment for a given individualSince we cannot put both samples together, we compare estimates of βacross the two samples, and β for academic entrepreneurs with β forPh.D.’s not originating from university employment

DensityLog(Earnings) Density0100000200000300000Salary (1993 US dollars)movers to entrepreneurship400000stayers in academiaNegative earnings comparisson500000

Log(Earnings) DensityDensityprior to moving for those who moveversus those who stay05000001000000Salary (1993 US dollars)movers to entrepreneurshipstayers in academiaStayers are on average better paid1500000

Log(Earnings) DensityDensitybefore and after movingonly for those moving0200000400000Salary (1993 US dollars)Before entrepreneurship600000In entrepreneurship800000

Returns to Academic EntrepreneurshipFixed effects paneldata icineEnt*EngineeringEnt*Foreign bornEnt*MaleEnt*MarriedEnt*Years ExperienceEnt*Years at last employerEnt*Tenure TrackEnt*University QualityNumber observations1,016**significant at 1% level, * significant at 5% level.N/A.068(.064)2,578

Next step Use coarsened exact matching to reducepotential imbalance in covariates betweenentrepreneurs and the control group Estimate yit Eit ( Xit ) A( lEit ) i t it Test against omitted variable bias

Main ResultsMeasureU.S.SwedenBi-annual academic entrepreneurship rate0.9%1.1%Bi-annual non-acad. entrepreneurship rate4.0%2.5%Relative entry rate25%44%Earnings difference academics to entr-15.1%-9.7%Earnings difference non-academics to entrepreneurs-16.0%-12.1%Two-year failure rate40%46%Non-academic failure raten.a.32%Percent returning to academia33%61%

Summary of Findings There is a higher relative rate of entry into entrepreneurship byacademics in Sweden than in the U.S.For academics, entrepreneurship does not pay well– Returns between 10% to 15% lower than staying employed– Income risk is three times higherAcademics in less attractive employment positions are more likely thanothers to become entrepreneurs – with lower wage, and not on tenure track position but fare equally well in entrepreneurshipEntrepreneurship spells are very short– over 40% exit within two years– many – in particular in Sweden – return to academia

Inferences The market for academic entrepreneurship seemsprivately risky, but liquid and highly mobile Professors respond to economic incentives Signs of over‐entry in both the U.S. and Sweden?– Financial encouragement of academic entrepreneurshipbeyond existing efforts needs to make plausible substantialsocial returns In both countries there is selection from the bottom ofthe ability distribution– Stimulating younger, tenure‐track academics shouldproduce greater marginal benefits for society than generalincentives for all academics Consulting and advisory roles may be more efficientthan full‐time efforts

Policy Advice Abolishing the Professor’s Privilege in Sweden wouldlikely lead to less – not more – academicentrepreneurship Consider improving the screening process to supportfewer academic entrepreneurs but with higherquality projects, or more loose affiliations (not full‐time) to business Do not expect great economic outcomes fromacademic entrepreneurs

EXTRA

Returns to non‐AcademicEntrepreneurshipFixed effects paneldata reign s at lastemployerEnt*Tenure TrackEnt*UniversityQualityNumber observationsLegend: **significant at 1% level, * significant at 5% level.Sweden

What are the private benefits? The private returns to entrepreneurship turnout to be negative, between ‐5% to ‐15% peryear (e.g. Hamilton, 2000; Woodward andHall, 2013)– People would be better off remaining employed

– The rate of STEM academic entrepreneurship – The earnings from commercialization One of the main differences: IPR regime. Cash‐flow rights and control right are very different. Bayh‐Dole (42%) vs Professor’s Privilege (100%) – Expect higher absolute rate of academic entrepreneurship in the U.S.

Academic entrepreneurship: time for a rethink? 9 As academic entrepreneurship has evolved, so too must scholarly analysis of academic entrepreneurship. There has been a rise in scholarly interest in academic entrepreneurship in the social sciences (e.g., economics, sociology, psychology, and political science) and several fields of business

To define the entrepreneurship. To explain the significance of Entrepreneurship. To explain the Entrepreneurship Development. To describe the Dynamics of Entrepreneurship Development. 1.1 Need and significance of Entrepreneurship Development in Global contexts It is said that an economy is an effect for which entrepreneurship is the cause.

harborfreight.com 4,500 4,000 20,000 900 tool retailer 1977 Eric Smidt CEO (800) 444-3353 Dole Food Co. Inc. One Dole Drive Westlake Village 91362 dole.com 4,5001 4,507 NA NA fresh fruit and vegetable producer 1851 David Murdock CEO, Chairman (818) 879-6600 5 Wonderful Co. 11444 W. Olympic B

dianne's/alden merrell desserts reynolds food packaging discovery products corporation reynolds metro diversified ceramics corporation rich products corporation-dry dole c-store rich products corporation-frozen dole foodservice frozen richardson brands company dole packaged foods richardson brands company dominex richelieu foods don miguel ricola

the alternative to frontrunner Hillary Clinton. But he pulled out of the race just weeks after establishing a formal exploratory committee in late 2006. A Bayh town meeting in New Hampshire had been completely overshadowed by Barack Obama’s first trip to the Granite State. Bayh, ever

Grimaldi et al. (2011) define academic entrepreneurship as efforts to commercialize innovations developed by academic scientists. –Includes: startups, patenting, licensing, university-industry partnerships We observe two forms of academic entrepreneurship: –New firms with the academic scientist as a founder (not only through TTO)

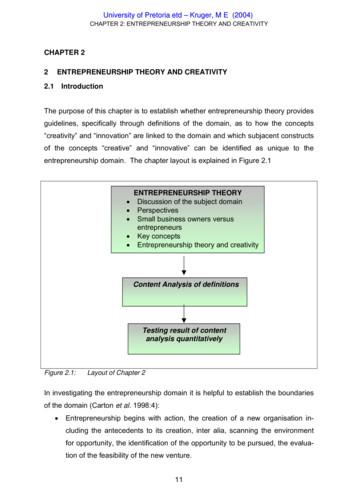

CHAPTER 2: ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY AND CREATIVITY ctives. epreneurs. reneurship. 3:49). thought on the meaning of entrepreneurship. One group focused on the characteris-tics of entrepreneurship (e.g. innovation, growth, uniqueness) while a second group focused on the outcomes of entrepreneurship (e.g. the creation of value).

Attila has been an Authorized AutoCAD Architecture Instructor since 2008 and teaching AutoCAD Architecture software to future architects at the Department of Architectural Representation of Budapest University of Technology and Economics in Hungary. He also took part in creating various tutorial materials for architecture students. Currently he .