Past And Present Conditions Along The Scenic Byway

past and Presentconditions alongthe scenic byway3

Historic laundress quarters at the American Camp unit of San Juan Island National Historical Park

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayThe distinctive Pacific Northwest Archipelago Experience.of the San Juan Islands begins with themarine passage across the Salish Sea.As the byway extends onto the islands,scenic country roads wind throughpicturesque landscapes, quaint villagesand hamlets, and other crossroadsand destinations. Visitors have manyopportunities to connect with the uniqueculture, history, and exquisite beauty ofthe marine and island environments thatare part of the byway experience.The islands have long been a haven forthose seeking an escape from the restof the world. Many places in the islandsattract guests throughout the year, butparticularly in the summer. Opportunitiesto be close to diverse naturalCorridor Management Planenvironments, from forests to beaches,and to view wildlife, from deer to orcawhales, are part of the allure of this place.The mild climate, abundant recreationoptions, and opportunities for peacefulrespite also attract people. It is no wonderthat many visitors fall in love with theislands and return time after time, somechoosing to make the San Juans theirpermanent or part-time home. Residentsof the islands include artists, pilots,shopkeepers, teachers, writers, peoplewho work in the fishing, agriculture, andtimber indutries, and others. The peopleof the islands whose families have livedhere throughout time, as well as thosewho call it home today, contribute muchto the rich story of this byway.Through understanding and exploringthe existing conditions in the San JuanIslands, unique resources of the bywaycan be identified, along with importantneeds. The existing physical conditions,history, and culture of the islandsintroduced in this section of the planset the stage for the byway’s story. Thissection also provides a review of existingplans and policies relevant to the SanJuan Islands Scenic Byway.3-1

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayNatural HistoryThe natural history of the islands, briefly summarized below,has influenced the spectacular scenic beauty and unique marineand geographic conditions that make the San Juans a worldclass destination.The San Juan Islands are thought to have originated as a resultof partial submergence of a mountain range that crosses thearea in a northwesterly direction. The islands and reefs representthe higher points in the range, while the valleys and ravines formthe channels and harbors. The Puget Trough, which lies betweenthe Cascade Mountains and the continental coast for the entirelength of Washington state, from Canada to Oregon, is the basinin which the San Juan Islands are located. The Puget Troughis a glaciated feature, and the submerged mountain rangewithin this basin that eventually became the islands may haveonce connected Vancouver Island to the mainland. During thePleistocene Ice Age, all of the islands were covered by glaciers.In some areas, the ice may have been more than one mile thick.The region’s highest peak, Mount Constitution on Orcas Island,bears glacial markings at its very top. The lowest point in theislands, a trench in Haro Strait, may have been carved out by theglaciers as well. Century by century, this huge ice sheet surgedand crunched southward over the top of what eventually becamethe San Juan Islands.Hiker gazing at the San Juan Islands from Orcas Island3-2Two distinct types of geologic landforms developed over millionsof years in the San Juans. The first consists of bedrock domesthinly covered with late Quaternary (glacial) sediments commonlyfound on San Juan and Shaw islands, as well as CypressSAN JUAN ISLANDS SCENIC BYWAY

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayView of the Cattle Point landscape and the south end of Lopez IslandIsland (in Skagit County). The secondtype, found on the islands of Lopez,Waldron, and Decatur, is composed ofbedrock buried beneath sediments morethan 300 feet thick in places. Neitherformation is exclusive to any singleisland. Portions of Orcas, Lopez, andWaldron islands have surface exposuresof bedrock, and parts of Orcas andSan Juan islands have thick glacialdeposits. Most of the intermontanevalleys and lowland areas of the islandsexpress a low, rolling topography andare underlain by a few feet to severalhundred feet of glacially-derived sand,gravel, and clays associated with theadvance and recession of the latestcontinental glaciers that rode over thearea from the north and east. This isin sharp contrast to the mountainousterrain dominated by bedrock at or nearthe land surface.Corridor Management PlanDistinctive glacial erratics can be foundin fields and forests across the islands.There are even places like the CattlePoint Interpretive Center where groovescan be seen from granite boulders(originally from the Canadian Rockies)that were dragged across native basaltlayers during the glacial era.ClimateThe climate of the San Juan Islands is mild,with about half the average annual rainfallas the Seattle area to the southeast and anaverage of 247 days with sunshine each year.The climate is influenced by themountains on the Olympic Peninsula tothe southwest and Vancouver Island tothe west and northwest. These influencescreate a “rain shadow” effect producingless rainfall and more sunny days in theSan Juans than many other areas in theregion. Precipitation at sea level increasesfrom south to north in the islands as therain shadow influence dissipates. Forexample, the average annual precipitationat the south end of Lopez Island is 19inches, while the northern portion ofOrcas Island receives 30 inches averageannual precipitation. Precipitation alsoincreases with higher elevation producinga maximum average annual precipitationof 45 inches on Mount Constitution.The maritime air surrounding the islandsalso moderates the climate. Summersare relatively short, cool, and dry, andwinters are mild and moderately drywhen compared to other areas in thePacific Northwest. However, when cold,arctic air funnels down the Fraser RiverValley from Canada, winter temperaturescan drop dramatically. Average hightemperatures in the summer are in the low70s (Fahrenheit), occasionally peaking inthe mid-80s. Average lows in the winterrange in the high 30s, at times dipping intothe low 30s/high 20s. Snow sometimesfalls on the islands in winter, typically onceor twice a year with accumulations of notmore than one or two inches.3-3

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayNatural ResourcesThe natural characteristics of the SanJuan Islands are extraordinary. Elevationand topography, soils, marine conditionsand hydrology, vegetation, diverseecosystems, and wildlife/marine life aresummarized below.Elevation andTopographyAbrupt changes in elevation occurthroughout the San Juan Islands andsurrounding waters. The maximumheight above sea level is found on MountConstitution with an elevation of 2,409feet. The deepest sounding recorded inthe area occurs in Haro Strait near StuartIsland, with a depth of 1,356 feet belowsea level. As such, the San Juan Islandregion presents an extreme relief of3,765 feet. The topography throughoutthe islands is diverse, with rolling terrainand valleys between low hills in manyareas. There are also areas of steepterrain as well as flatter or moderatelysloped prairies and pasture lands.On Orcas Island, about one-third of the57 square miles of the island is above3-4View of Clark Island and other small islands in the archipelago from the top of Mount Constitution at Moran State Park500 feet in elevation, and about 14percent is above 1,000 feet. Glacialinfluences in the terrain are evidentthroughout the islands. For example,Orcas Island is nearly cut into two islandsby a narrow fjord-like harbor known asEast Sound, which opens towards thesouth and merges with Lopez Sound.SoilsSoils in the San Juan Islands region arehighly variable. Nearly one hundredtypes have been defined and described.They are typically rocky, coarse-textured,extremely well drained, and poor innutrients. In many areas the soil layeris very thin. However, a few soil types,such as those filling low-lying out-washbasins, are composed of extremely finesand and clay. Most wetland areas inthe San Juan Islands are underlain withthese types of soils. The availabilityof clay soils has led to various potteryoperations around the islands.Marine Conditionsand HydrologyMarine conditions include the saltwaterenvironments. Kelp and eelgrass beds,spawning beaches, enclosed bays androcky reefs provide diverse habitats fordifferent life stages of many species ofmarine life. The marine environment isfragile, subject to many influences in waterSAN JUAN ISLANDS SCENIC BYWAY

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayand on land. Habitat destruction caused by shoreline development,overfishing, and the introduction of invasive, non-native speciesreduce the diversity and integrity of marine ecosystems. Becausemarine and upland ecosystems are connected, every local propertyand business owner has a role in determining the health of themarine ecosystem. Given these concerns, several organizationsand agencies joined together to designate a Marine StewardshipArea and develop a Marine Management Workbook for thatarea. The workbook is designed to help local island communitiesand others identify sites for marine stewardship and applymanagement strategies. The Marine Stewardship Area wasofficially adopted by San Juan County in 2004.The average water temperatures in the seas surrounding the SanJuan Islands are fairly cold, ranging from 44ºF in the winter to51ºF at the height of summer, in August. During periods of springtides there can be a 13-foot tidal difference within a six-hourduration. Such a large variation in water levels is the result ofnearly constant movement of a huge volume of water, creatingstrong and sometimes dangerous currents throughout the region.The great blue heron is commonly seen across the islands.Corridor Management PlanOver11,000 years ago, the final melting of the glacierssupercharged this area with groundwater. All available undergroundspaces were filled as meltwater percolated as deeply as possibleinto cracks, pores, and pockets within the bedrock. Today, all ofthe “resupply” or “recharge” of this groundwater comes fromlocal rainfall. About two-thirds of the precipitation returns to theatmosphere by evapotranspiration. The remaining one-third runsoff in small creeks, with the total runoff varying across the islandsproportionately to precipitation. The most runoff is dischargedfrom creeks in the Mount Constitution area of Orcas Island.3-5

Madrona trees line the rocky shores of San Juan Island

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayStreamflow in the San Juan Islands is intermittent. The highestdischarges occur from December through February, and usually verylittle to no flow occurs from late May or early June to late Octoberor mid-November. Runoff is directly dependent upon precipitation,which varies with distance from the Olympic Mountains (the rainshadow effect) and relative relief within individual watersheds.Lakes and ponds are found throughout the islands. SummitLake, Mountain Lake, and Cascade Lake on Orcas Island receiverunoff from the area around Mount Constitution, which is thewettest area in San Juan County. Summit Lake is formed by asmall concrete dam at its southeast end. Water released from thisreservoir flows into Mountain Lake.Although surface water runoff in the San Juans is low compared to otherareas in western Washington, surface water ponding of runoff in lakes,reservoirs, and dug pits is the primary source of drinking, irrigation,and stock water. Trout Lake and Briggs Pond on San Juan Island supplydomestic water for the Town of Friday Harbor and Roche Harbor,respectively. Rosario on Orcas Island uses Cascade Lake. The Olgaand Doe Bay water systems also on Orcas, depend on Mountain Lake.Eastsound uses Purdue Reservoir as a back up for well-water sources.Wells in San Juan County are generally produced from two majoraquifer types: glacial/interglacial aquifers and bedrock aquifers.Aquifers are geologic zones where groundwater is found and canbe extracted. Most wells in the County obtain water from bedrockaquifers. Generally, groundwater flows radially outward from thecenters of the islands toward the shorelines. Because of a highratio of shoreline length to land area in the San Juans, there is anappreciable flow of groundwater seaward.Corridor Management PlanDiverse Ecosystems and VegetationA diverse range of ecosystems exist in the San Juan Islands,including marine and coastal environments such as reefs andbeaches, as well as inland wetlands and bogs, prairies, riparianareas, upland forests, and more. Ecosystems are drier at lowerelevations and southward, and wetter at higher elevations andnorthward. The interplay of latitude, elevation, and patchworksoil types creates a great variety of microhabitats and plantcommunities. Several important habitats and ecosystems arehighlighted below. Although the scenic byway only extends acrosstwo islands, there are 176 islands and reefs at high tide and 743at low tide in the archipelago. San Juan County has more than408 miles of rocky and sandy waterfront, with more shorelinethan any other county in the nation and a little less than 20percent of the total shoreline in the Salish Sea.Eelgrass habitat is particularly important in the San Juan Islandsbecause all 22 populations of Puget Sound Chinook Salmon(now listed as an endangered species) use the San Juans to growbigger and stronger before their journey into the open ocean.Eelgrass habitat areas also provide shelter, feeding and rearingrefuges for crab, rock fish, herring, sea anemones, marine worms,snails, limpets, other sealife and fish, and birds. Eelgrass bedshave been in dramatic decline due to mooring buoys and otherstructures, as well as shoreline alterations such as bank armoring.Shoreline vegetation benefits the marine ecosystem by providingshade for spawning fish. A recent study reported by the SanJuan Initiative showed that 88 percent of the 1977 forest coverremains along shorelines of the islands. However, the greatestlosses of forest cover in the islands overall have occurred along3-7

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayarmored banks of shorelines. This hasaltered beach environments and resultedin a loss of shading, leaf litter, andother organic material important to theshoreline habitat.created concerns about potential impactsto shoreline habitats. Of the 4.5 miles offeeder bluffs in the San Juan Initiative’sstudy area, 30 percent were found tohave been armored.Rocky shores make up between 50 to 60percent of San Juan Islands’ shoreline.These areas may have kelp beds orrockfish habitats that require clean waterand nutrients from adjacent lands.Feeder bluffs replenish beach environmentswith sand and gravel constantly beingtransported by currents, tides, and waves.Feeder bluffs are important contributors tobeach habitats where there are spawningforage fish, as well as bedding material foreelgrass beds. Armoring and altering offeeder bluffs throughout the islands haveSandy beaches throughout the islandsprovide important habitat for sand lanceand surf smelt, which are forage fish anda basic food source for many species.Sandy beaches serve as incubators forthese species’ eggs. Research has shownthat shoreline armoring has a directimpact on forage fish.Open, rocky outcrops with rocky knollsand steep slopes are a commonfeature, and plant communities inthis terrain are survivors of extremeconditions. Lichens and mosses surviveon bare rock, and grasses and herbsare common in pockets that retainsome soil and moisture.Old growth snag at English Camp3-8Example of rocky shores in the San Juan IslandsCamas flower at San Juan Island National Historical ParkSAN JUAN ISLANDS SCENIC BYWAY

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y waySince the region’s islands were exposed tothe air by receding glaciers (estimated tohave occurred about 11,000 to 13,000years ago), there has been continuouscolonization by plants and animalsnew to the area. Some have flourished,while others unable to compete or find asupportive niche have vanished.Due to their isolation relative to themainland, some long established plantand animal species are becominguniquely diverse. For example, a studyof the rare brittle cactus in westernWashington has revealed the apparentbiogeographic development of at leastfour different island “morphs” of thisplant. On some islands the spines arelarger and differently colored from theaverage individual. On other islands thepads have a new shape and color.Wetlands on the islands range fromlimited emergent wet meadows to freshwater marshes and open water lakes.At the head of some shallow baysand lagoons, small estuaries and saltmarshes of incredible productivity exist.Naturally-occurring land cover in theSan Juan Islands includes second-Corridor Management PlanDrift log on Cattle Point Beach3-9

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y waygrowth conifer forests, hardwood forests, scrub and shrub plantcommunities, and open prairies. Rock outcrops and beaches arenon-vegetated land cover types that also occur naturally on theislands. Over 800 kinds of vascular plants have been catalogedin the San Juan Islands, two-thirds of which are native.Due to conditions and influences unique to the San Juan Islands,ecosystems, vegetation, and the mix of wildlife using these areasfor habitat can be distinctive from other places in Puget Soundand the surrounding region. For example, forests in San JuanCounty are much drier than those of the mainland Puget lowland.Many forested areas are lacking in underbrush and have anopen canopy and park-like appearance. Douglas fir dominatesin most areas but varies substantially in growth habit dependingon environmental conditions. Forest character in the San JuanIslands changes from site to site as a result of wind, sunlight, soiltype and depth, topography and moisture, as well as humanmanagement. Stands of large virgin timber, some over 300years old, still exist in isolated pockets among the islands withexceptionally large specimens of Douglas fir, western red cedar,Sitka spruce, and big leaf maple. Other native trees such aswestern hemlock, grand fir, Pacific yew, and shore pine also exist.The lime industry that flourished at the turn of the century relied ontimber as fuel for kilns. This had a devastating effect on the forestsof the islands. There are very few old growth areas left on SanJuan Island, but some areas exist on Orcas Island.Open prairies create a patchwork across the islands thatcontrasts with the forests. The prairies are typically found on thesouth sides of the islands and are well-drained sites subject to3-10Walking trail through dense forest near Beaverton Valley Road on San Juan IslandSAN JUAN ISLANDS SCENIC BYWAY

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y waydrying winds and exposure to the sun.Garry oak, Rocky Mountain juniper andPacific madrona are able to anchor inthe thin soils in these areas.Prairies were once fairly common inthe Puget Sound and Salish Sea regions.As glaciers retreated, grasses and otherprairie plants were first to colonize thelandscape. Exposure to harsh conditionsof direct summer sun, drying effects ofwind, and low precipitation in the "rainshadow" of the Olympic Mountainsallowed the prairies to thrive intact.But landscapes constantly evolve inresponse to climate change, geologicprocesses, and human impact. In theSan Juan Islands, when Europeansbrought livestock and started cultivatingthe land, they upset the delicatebalance created by native peoples,who routinely set the prairie on fire inorder to maintain and enhance thegrowth of camas, a diet staple, andmaintain the prairie ecosystem overall.Settlers introduced invasive, nonnative plants that choked out nativeprairie plants and animals such as theEuropean rabbit, which has transformedacres of delicate native wildflowers intobarren landscapes.Corridor Management PlanThese types of influences have affectednatural prairie ecosystems throughoutPuget Sound and Washington, and as aresult only three percent of the historicextent of Washington’s prairies stillremain intact. The other 97 percent havebeen destroyed or heavily altered.The Garry oaks/prairie ecosystem isunique and supports a number of rare anddiverse species. In the San Juan Islands,Garry oaks fall at the northern limit ofthe species’ range with many speciesfound here that are scarce elsewhere.Remnant patches of the Garry oaks/prairie ecosystem exist at the AmericanCamp and English Camp units of the SanJuan Island National Historical Park, aswell as elsewhere in the islands. Prairiesspan nearly half the acreage at AmericanCamp, from the bluffs along South Beachto the south-facing slopes of MountFinlayson. When American naturalistC.B.R. Kennerly explored San Juan Islandin 1860, his British and American hoststook him to see “Oak Prairie,” the only oakA view of Mount Baker and Griffin Bay from the prairie at American Camp3-11

Wildflowers color the serene prairie landscape.

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayCalifornia buttercups sprawling over the Garry oak/prairie ecosystemcommunity he recorded during his explorations of the San JuanGulf archipelago in 1857-1860. According to contemporarymaps, Oak Prairie was located at the head of San Juan Valley inwhat was (and is) plainly a seasonal wetland with deep alluvialsoils. Today, oak prairies are found on Waldron and Samishislands, as well as other locations in the county.of the San Juan Islands include Idaho fescue, blue wild rye, andAlaska onion grass.The Garry oaks/prairie ecosystem often support or co-exist with rarespecies of plants such as California buttercup, golden paintbrush(listed as a threatened species by the Washington Department ofFish and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife), white meconella, erectpygmyweed, common blue-cup, Nuttall’s quillwort, rosy owlclover,coast microseris, white-top aster and annual sandwort. Garry oakcommunities also can include more common colorful species suchas white fawn lilies, camas, chocolate lilies, and brodeaias. Thepredominant grass species found in the prairies and grasslandsThe Gary oaks/prairie ecosystem also supports wildlife such asthe island marble butterfly, moss elfin butterfly, streaked hornedlark, purple martin, and Townsend's vole.Corridor Management PlanMany of these species are culturally significant to native peoples.For example, Camas is considered to be the most important“root” food to Coast Salish peoples.The National Park Service (NPS) and other land managers aretaking steps to restore prairies in the islands. The goal is to restoreprairie communities dominated by native grasses and plants thatsupport habitat for native wildlife and rare species. This goal is alsocompatible with NPS goals for cultural landscape preservation.3-13

The red fox is a non-native species introduced to San Juan Island in the 20th century. Photo by Julia Vouri, taken at San Juan Island National Historical Park

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayWildlife/Marine LifeThe diverse ecosystems and habitatsin the San Juan Islands support anabundance of wildlife, including marinelife and fish. The marine habitatsare home to species of salmon, orca‘killer,’ gray, and Minke whales, Dall’sporpoise, steller sea lions, river and seaotters, lingcod, 26 species of rockfish,and approximately 150 species ofmarine birds.There are three resident orca whale pods(J, K & L) that inhabit the waters, mostfrequently April through September. Asubspecies of the resident orcas calledtransients, which are smaller in size, alsoinhabit the area and are seen year-round.The Salish Sea orcas of the San JuanIslands are officially known as SouthernResidents, and this distinct populationwas listed for protection under thefederal Endangered Species Act in late2005. The population experienced analarming decline of almost 20 percentfrom 1996 to 2001, when only 79animals were counted. At its peak in the1990s, the population was as high as97 animals. The National Oceanic andAtmospheric Administration (NOAA)Corridor Management PlanOrca whales off San Juan IslandFisheries Service has been studyingthe population, and their research hasconfirmed that the availability of prey,pollution, and effects from vessels andsounds are major threats to the whales'health, as well as the whales' inherentlysmall population size.NOAA Fisheries Service has releaseda recovery plan for the region's orcawhales. NOAA has stated that recoveryof the region's iconic marine mammalswill be a long-term effort requiringcommunity support to help restore thepopulation to healthy levels. The planidentifies ongoing conservation programsand calls for action in a variety of areas,including improving availability ofprey by supporting salmon restorationin the region, reducing pollution andcontamination, and monitoring the effectsof vessel traffic and underwater noise.Over 291 species of birds overallhave been recorded in the San JuanArchipelago, and it is one of the mostimportant regional locations for breeding,migrating and wintering of seabirds.3-15

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayThe habitats of the San Juan Islands support one of the largestbald eagle populations in the lower United States. There aremore nesting pairs in San Juan County, 89 at last count, thanthere are in any other county in the state. One of the pairs hasbeen nesting above American Camp since 1995.The islands also host a rare golden eagle population. Otherbirds of distinction found in the area include loons, vultures,herons, peregrine falcon, merlin, purple martin, trumpeter swans,Cooper’s hawk, and the marbled murrelet. Each year at EnglishCamp, an osprey pair establishes a nest in a snag above theparade grounds. Visitors can track the progress of the young viaa bird scope. Steller’s jay was once found on San Juan Island,but post 1930 their distribution has largely been restricted toOrcas Island for unknown reasons.American bald eagle3-16Twenty-four different terrestrial mammal species, includingriver otter, mink, and Columbia black-tailed deer, are foundin San Juan County. Deer populations in the islands vary bysize and coloring. Deer on Orcas Island are typically smallerwith more mottled white markings. Rabbits and foxes, bothnon-native species, can be seen in the open prairies of theislands. As mentioned previously, the European rabbits’ damageto the natural prairie and grasslands has been a significantconcern. Small mammals include the white-footed deer mouse,Townsend’s vole, shrews, and other species. The northern flyingsquirrel was confirmed present on San Juan Island in 1995.Some sources suggest that this species and the Douglas squirrel(only found recently on Orcas Island and not elsewhere in theSan Juans) were introduced to the islands. The eastern graysquirrel and eastern fox squirrel have also been found on OrcasSAN JUAN ISLANDS SCENIC BYWAY

pa s t a n d p r e s e n t c o n d i t i o n s a l o n g t h e s c e n i c b y wayIsland, as well as on nearby Crane Island, but are not typicallyfound elsewhere. Beavers are found in some parts of OrcasIsland and have been present on San Juan and Lopez in thepast. Amphibians and reptiles that may be observed in the SanJuans are the rough-skinned newt, red-legged frog, western toad,and northern alligator lizard. These species, as well as manybirds and freshwater fish, rely heavily on the wet woodlands andriparian habitats scattered across the islands.Several wildlife species in the San Juan Islands and surroundingwaters are at risk, including orca whales (listed as endangeredas discussed above), as well as Chinook salmon (threatened),coho salmon (species of concern), steelhead (threatened),Bocaccio rockfish (endangered), Cherry Point herring (currentlyunlisted but of concern locally) and canary and yelloweye rockfish(threatened). Several organizations and agencies have beenworking to improve nearshore habitat important for forage fishand salmon, such as eelgrass beds, canopy kelp areas, andshallow protected bays where smelt, sand lance, herring, andother species that are prey for salmon exist.Island marble butterflyCorridor Management PlanDeer on San Juan IslandOther species of concern include the bald eagle, peregrinefalcon, northern goshawk, northern sea otter, northwesternpond turtle, olive-sided flycatcher, Oregon vesper sparrow,valley silverspot butterfly, Pacific lamprey, river lamprey, westerntoad, both the long-eared and long-legged myotis, and PacificTownsend's big eared bat.The island marble butterfly, a unique sub-species of the largemarble found east of the Cascades, is another example of aspecies at risk in the San Juan Islands. The species, known forits beautiful creamy white coloring with green marbling on theunderside of its wings has been listed for possible designationas endangered, threatened, or sensitive. Once common in opengrasslands and woodlands, the island marble was believed extinctfor decades until one small population was found on San JuanIsland in 1998. More recently, the island marble has been foundinhabiting small areas on San Juan Island and Lopez Island.These are the only places in the world that this tiny creature isknown to exist! Local

past and present conditions along the scenic byway of the San Juan Islands begins with the marine passage across the Salish Sea. As the byway extends onto the islands, scenic country roads wind through picturesque landscapes, quaint villages and hamlets,

The passive gerund can have two forms : present and past. The present form is made up of being the past partiilicipleof themainverb,and the past form ismadeup of having been the past participle of the main verb. Present: being the past participle Past: having been the past participle

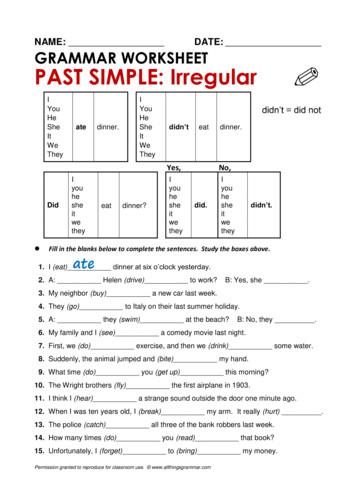

WORKSHEET 5 : Past form of verb “ To Be “ WORKSHEET 6 : Past form of verb “ To Be “ WORKSHEET 7 : Simple Past Tense . WORKSHEET 8 : Simple Past and Past Continuous . WORKSHEET 9 : Simple Past and Past Continuous . WORKSHEET 10 : Present Perfect Tense . WORKSHEET 11 : Present Perfect Tense vs Present Perfect Continuous

Textbook: R. Murphy, English Grammar in Use, B1-B2, Cambridge University Press Present and past: Present continuous (I am doing) Present simple (I do) Present continuous and present simple 1 (I am doing and I do) Present continuous and present simple 2 (I am doing and I do) Past simple (I did) Past continuous (I was doing)

Present Continuous Present Continuous: Spelling U7 Simple Present vs. Present Continuous: Non-Action Verbs Simple Present vs. Present Continuous: Yes/No Questions U8 Future: Will and Be going to Future: Yes/No Questions with Will and Be going to U9 Simple Past Simple Past: Spelling of Regular Verbs U10 Simple Past: Irregular Verbs U11 Can and .

1 the past tense of write _ 2 the past tense of begin _ 6 last year he _ football 7 the past tense of watch _ 10 the past tense of rain _ 12 the past tense of eat _ 13 the past tense of stand _ 14 the past tense

A regular verbforms its past and past participle by adding –d or –ed to the base form. BASE FORM use pick PRESENT PARTICIPLE [is/are] using [is/are] picking PAST used picked PAST PARTICIPLE [has/have] used [has/have] picked EXERCISE A Supply the present participle,past,and past

Verb "to be" in Present and Past Simple Tense 18 15. Verb "to have" in Present and Past Simple Tense 19 16. Verbs in Present Simple Tense 20 17. Present Simple Continuous 21 18. Do - Verb 22 19. Did - Verb 23 20. Regular Verbs in Past and Perfect Simple Tense 24 21. Irreguar Verbs in Past and Perfect Simple Tense 25 - 26

on criminal law reforms which I had begun in 2001 when still working as an attorney. Observing the reforms in action and speaking with judges and lawyers not only helped to inform my own work, but also helped me to see how legal reform operates in a