Romanian Grammar

Romanian Grammarby Dana Cojocaru SEELRC 2003

1Cojocaru Romanian Grammar0. INTRODUCTION0.1. Romania and the Romanians0.2. The Romanian language1. ALPHABET AND PHONETICS1.1. The Romanian alphabet1.2. Potential difficulties related to pronunciation and reading1.2.1. Pronunciation1.2.1.1. Vowels [ ǝ ] and [y]1.2.1.2. Consonants [r], [t] and [d]1.2.2. Reading1.2.2.1. Unique letters1.2.2.2. The letter i in final position1.2.2.3. The letter e in the initial position1.2.2.4. The ce, ci, ge, gi, che, chi, ghe, ghi groups1.2.2.5. Diphthongs and triphthongs1.2.2.6. Vowels in hiatus1.2.2.7. Stress1.2.2.8. Liaison2. MORPHOPHONEMICS2.1. Inflection2.1.1. Declension of nominals2.1.2. Conjugation of verbs2.1.3. Invariable parts of speech2.2. Common morphophonemic alternations2.2.1. Vowel mutations2.2.1.1. the o/oa mutation2.2.1.2. the e/ea mutation2.2.1.3. the ă/e mutation2.2.1.4. the a/e mutation2.2.1.5. the a/ă mutation2.2.1.6. the ea/e mutation2.2.1.7. the oa/o mutation2.2.1.8. the ie/ia mutation2.2.1.9. the â/i mutation2.2.1.10. the a/ă mutation2.2.1.11. the u/o mutation2.2.2. Consonant mutations2.2.2.1. the c/ce or ci mutation2.2.2.2. the g/ge or gi mutation2.2.2.3. the s/ş i mutation2.2.2.4. the st/şt i mutation2.2.2.5. the str/ştr i mutation2.2.2.6. the sc/şt i or e mutation2.2.2.7. the şc/şt e or i mutation2.2.2.8. the t/ţ i or e mutation2.2.2.9. the d/z i/â or ă mutation2.2.2.10. the z/j i mutation2.2.2.11. the l/Ø i mutation

22.2.2.12. the n/Ø i mutation3. NOMINALS3.1. Noun3.1.1. Gender of nouns in the singular3.1.1.1. Assigning gender3.1.1.1.1. Noun ending3.1.1.1.2. Lexical meaning3.1.1.1.3. The 'one-two' test3.1.2. Number3.1.2.1. Forming the plural3.1.2.1.1. Masculine: un – doi3.1.2.1.2. Feminine: o – două3.1.2.1.3. Neuter: un - două3.1.2.2. Plural endings3.1.2.2.1. The ending -i3.1.2.2.2. The ending -le / -ele3.1.2.2.3. The endings -e and -uri3.1.3. Case3.1.3.1. Case forms3.1.3.1.1. Declension with the indefinite article3.1.3.1.2. Declension with the definite article3.1.3.2. Accusative (direct object) with and without the preposition pe3.1.3.2.1. The direct object with pe3.1.3.2.2. The direct object without pe3.1.3.3. The accusative with other prepositions3.1.3.4. Genitive and dative cases3.1.3.4.1. Differentiating the genitive and dative3.1.3.4.1.1. The genitive3.1.3.4.1.2. The dative3.1.3.4.2. Proper names of persons in the genitive-dative3.1.3.5. Vocative3.1.3.5.1. Forming the vocative3.1.3.5.2. Usage of the vocative3.1.3.5.2.1. Adjective noun in the vocative3.1.3.5.2.2. Adjective possessive noun in the vocative3.2. Article3.2.1. The definite and the indefinite article3.2.1.1. The indefinite and the definite article in the singular3.2.1.1.1. Indefinite article3.2.1.1.2. Definite article3.2.1.2. The indefinite and the definite article in the plural3.2.1.2.1. Indefinite article3.2.1.2.2. Definite article3.2.1.3. Article usage and omission3.2.2. The demonstrative or adjectival article3.2.3. The possessive or genitival article3.3. Adjective3.3.1. Adjectival agreement3.3.1.1. Forming the feminine and the plural of the adjectives3.3.1.2. Four-form adjectives3.3.1.3. Three-form adjectives3.3.1.4. Two-form adjectives

33.3.1.5. One-form adjectives3.3.2. The usage of the adjectives in pre-position3.3.3. Adjectival declension3.3.4. Degrees of comparison of the adjective3.3.4.1. The comparative degree3.3.4.1.1. The comparative of superiority3.3.4.1.2. The comparative of equality3.3.4.1.3. The comparative of inferiority3.3.4.2. The superlative degree3.3.4.2.1. The superlative relative of superiority3.3.4.2.2. The superlative relative of inferiority3.3.4.2.3. The superlative absolute3.3.4.3. Adjectives that do not form degrees of comparison3.4. Pronoun3.4.1. Personal pronouns3.4.1.1. The nominative case of the personal pronouns3.4.1.2. The accusative case of the personal pronouns3.4.1.2.1. Full and clitic forms of the accusative3.4.1.2.2. The personal pronoun used as a direct object3.4.1.3. The dative case of the personal pronouns3.4.1.3.1. Full and clitic forms of the dative3.4.1.3.2. The personal pronoun used as an indirect object3.4.1.4. Basic patterns of combining personal pronouns in the accusative / dative withverbs3.4.1.4.1. With the verb in the present indicative3.4.1.4.2. With the verb in the compound perfect3.4.1.4.3. With the verb in the future 1 indicative3.4.1.4.4. With the verb in the present subjunctive3.4.1.5. Differentiating the accusative and the dative unstressed personal pronouns3.4.1.6. Verbal constructions with personal pronouns in the accusative and dative3.4.1.7. Combinations of double personal pronouns (dative and accusative) with verbs3.4.1.7.1. With the present, compound perfect and future 1 indicative3.4.1.7.2. With the present subjunctive3.4.2. Pronouns of politeness3.4.2.1. The nominative case of the pronouns of politeness3.4.2.2. Declension of the pronouns of politeness3.4.3. Reflexive pronouns3.4.3.1. Clitic forms of the reflexive pronouns3.4.3.2. The long form of the reflexive pronouns3.4.4. Pronouns of reinforcement3.4.5. Possessive pronouns and pronominal adjectives3.4.5.1. The possessive pronominal adjectives in the nominative-accusative case3.4.5.2. The possessive pronouns in the nominative-accusative case3.4.5.3. The declension of the possessive pronominal adjectives3.4.5.4. The possessive value of the unstressed personal and reflexive pronouns in thedative3.4.6. Demonstrative pronouns and pronominal adjectives3.4.6.1. The demonstrative pronouns of proximity and remoteness in the nominative case3.4.6.2. The demonstrative pronouns of remoteness in the nominative case3.4.6.3. The demonstrative pronominal adjectives of proximity and remoteness3.4.6.4. The declension of the demonstrative pronouns / pronominal adjectives ofproximity and remoteness

43.4.6.5. The demonstrative pronouns and pronominal adjectives of differentiation andidentification3.4.6.5.1. The demonstratives of differentiation3.4.6.5.2. The demonstratives of identification3.4.7. Interrogative / relative pronouns and pronominal adjectives3.4.7.1 Relative pronouns vs. interrogative pronouns3.4.7.2. The interrogative pronouns cine and ce in the nominative3.4.7.3. The interrogative pronoun / pronominal adjective care in the nominative3.4.7.4. The declension of the interrogative pronouns / pronominal adjectives cine, ce andcare3.4.7.4.1. The interrogative pronoun cine3.4.7.4.2. The interrogative pronoun / pronominal adjective ce3.4.7.4.3. The interrogative pronoun / pronominal adjective care3.4.7.5. The relative pronoun / adjective care3.4.7.6. The relative pronouns cel ce / cel care3.4.7.7. The relative pronoun ceea ce3.4.8. Indefinite and negative pronouns3.4.8.1. The indefinite pronouns ceva, altceva and orice3.4.8.2. The indefinite pronouns cineva, altcineva and oricine3.4.8.3. The negative pronouns nimeni and nimic3.4.8.4. The indefinite pronouns / pronominal adjectives unul / un and altul / alt in thenominative case3.4.8.5. Indefinite and negative pronouns / pronominal adjectives based on unul / un in thenominative3.4.8.5.1. The indefinite pronoun / pronominal adjective vreunul / vreun3.4.8.5.2. The negative pronoun / pronominal adjective nici unul / nici un3.4.8.6. The declension of the indefinite pronouns / pronominal adjectives unul, vreunuland of the negative pronoun / pronominal adjective nici unul3.4.8.7. The indefinite pronoun / pronominal adjective altul / alt3.4.8.8. The indefinite pronouns / pronominal adjectives fiecare and oricare3.4.9. Reduplication of pronominal complements3.4.9.1. The double expression of the direct and indirect object3.4.9.1.1. The anticipation of the direct object3.4.9.1.2. The reiteration of the direct object3.4.9.1.3. The anticipation of the indirect object3.4.9.1.4. The reiteration of the indirect object3.5. Quantitative expressions and numerals3.5.1. Quantitative pronouns and adjectives3.5.1.1. The interrogative / relative pronoun / pronominal adjective cât in the nominativecase3.5.1.2. The indefinite pronoun / pronominal adjective atât in the nominative case3.5.1.3. The indefinite pronouns / pronominal adjectives oricât and câtva in the nominativecase3.5.1.4. The indefinite pronoun / pronominal adjective tot in the nominative case3.5.1.5. The declension of the quantitative pronouns / pronominal adjectives cât, atât,oricât, câtva and tot3.5.1.6. Adjectives of indefinite quantity3.5.2. Cardinal numerals3.5.2.1. The cardinal numerals from 0 to 103.5.2.2. The cardinal numerals from 11 to 193.5.2.3. The cardinal numerals from 20 to 993.5.2.4. The cardinal numerals 21, 22, ; 31, 32, ; 41, 42, ; etc.

53.5.2.5. The cardinal numerals 100 and 1.0003.5.2.6. The cardinal numerals 1.000.000 and 1.000.000.0003.5.2.7. Compound cardinal numerals over 1003.5.2.8. The genitive and the dative of the cardinal numerals3.5.3. Other types of numerals3.5.3.1. The distributive numeral3.5.3.2. The collective numeral3.5.3.3. The adverbial numeral3.5.3.4. The multiplicative numeral3.5.3.5. The fractional numeral3.5.4. The numerical approximation3.5.5. Ordinal numerals3.5.5.1. Forming the ordinal numerals3.5.5.2. Declension of ordinal numerals3.5.5.3. The usage of the ordinal numerals4. VERB4.1. Introduction to the verb4.1.1. Basic information about verb and conjugation4.1.2. Identifying the conjugation of a verb4.1.3. The infinitive4.1.4. The past participle4.1.5. Auxiliaries used to form the compound tenses4.1.6. Infixes4.1.7. Verbal homonyms and homographs4.1.7.1. Verbal homonyms4.1.7.2. Verbal homographs4.1.8. Forming the negative of the verbs4.1.9. The interrogative of the verbs4.2. Personal moods4.2.1. The indicative4.2.1.1. The present indicative4.2.1.1.1. The present indicative of the verbs in -a (1st conjugation)4.2.1.1.1.1. Model 1 – without infix4.2.1.1.1.1.1. Stem of the infinitive ending in a consonant4.2.1.1.1.1.2. Stem ending in a consonant r / l4.2.1.1.1.1.3. Stem ending in -i after vowel4.2.1.1.1.1.4. The verb a întârzia4.2.1.1.1.1.5. The verb a continua4.2.1.1.1.2. Model 2 – with the infix -ez-/-eaz4.2.1.1.1.2.1. Stem ending in a consonant, including r/l4.2.1.1.1.2.2. Stem ending in c/g4.2.1.1.1.2.3. Stem ending in -i4.2.1.1.2. The present indicative of the verbs in -ea (2nd conjugation)4.2.1.1.3. The present indicative of the verbs in -e (3rd conjugation)4.2.3.1.1.3.1. Stem ending in a consonant, other than -n4.2.3.1.1.3.2. Stem ending in -n4.2.3.1.1.3.3. Stem ending in a consonant r/l4.2.3.1.1.3.4. Stem ending in a vowel4.2.1.1.4. The present indicative of the verbs in -i (4th conjugation)4.2.1.1.4.1. Model 1 – without infix4.2.1.1.4.1.1. Stem of the infinitive ending in a consonant, other than-n

64.2.1.1.4.1.2. Stem ending in -n4.2.1.1.4.1.3. Stem ending in a vowel, mostly -u4.2.1.1.4.2. Model 2 – with the infix -esc-/-eşt4.2.1.1.4.2.1. Stem ending in a consonant4.2.1.1.4.2.2 Stem ending in a vowel, mostly -u4.2.1.1.5. The present indicative of the verbs in -î (4th conjugation)4.2.1.1.5.1. Model 1 – without infix4.2.1.1.5.2. Model 2 – with the infix -ăsc-/-ăşt4.2.1.1.6. The present indicative of irregular verbs4.2.1.1.7. Using the present indicative4.2.1.2. The compound perfect indicative4.2.1.2.1. Forming the compound perfect indicative4.2.1.2.2. Using the compound perfect indicative4.2.1.3. The imperfect indicative4.2.1.3.1. Forming the imperfect indicative4.2.1.3.2. Using the imperfect indicative4.2.1.4. The simple perfect indicative4.2.1.4.1. Forming the simple perfect indicative4.2.1.4.2. Using the simple perfect indicative4.2.1.5. The pluperfect indicative4.2.1.5.1. Forming the pluperfect indicative4.2.1.5.2. Using of the pluperfect indicative4.2.1.6. The future indicative4.2.1.6.1. Forming the futures of the indicative4.2.1.6.1.1. Forming the future 1 indicative4.2.1.6.1.2. Forming the future 2 indicative4.2.1.6.1.3. Forming the future 3 indicative4.2.1.6.2. Using of the future indicative4.2.1.7. The future perfect indicative4.2.1.7.1. Forming the future perfect indicative4.2.1.7.2. Using the future perfect indicative4.2.1.8. The future in the past indicative4.2.1.8.1. Forming the future in the past indicative4.2.1.8.2. Using the future in the past indicative4.2.2. The imperative4.2.2.1. Forming the imperative4.2.2.2. Combining the imperative with clitic pronouns4.2.3. The subjunctive4.2.3.1. The present subjunctive4.2.3.1.1. Basic rules of forming the present subjunctive4.2.3.1.1.1. Forming the present subjunctive, 3rd person singular and plural,of the regular verbs4.2.3.1.1.2. The present subjunctive of the irregular verbs4.2.3.1.2. Using the present subjunctive4.2.3.2. The past subjunctive4.2.3.2.1. Forming the past subjunctive4.2.3.2.2. Using the past subjunctive4.2.3.3. Structures with the verb a putea4.2.4. The optative-conditional4.2.4.1. The present optative-conditional4.2.4.1.1. Forming the present optative-conditional4.2.4.1.2. Using the present optative-conditional

74.2.4.2. The past optative-conditional4.2.4.2.1. Forming the past optative-conditional4.2.4.2.2. Using the past optative-conditional4.2.5. The presumptive4.2.5.1. The present presumptive (forms and usage)4.2.5.2. The present progressive presumptive (forms and usage)4.2.5.3. The past presumptive (forms and usage)4.3. Non-personal moods4.3.1. The infinitive4.3.2. The past participle4.3.3. The gerund4.3.3.1. Forming the gerund4.3.3.2. Using the gerund4.3.4. The supine4.4. Voice4.4.1. Reflexive voice4.4.1.1. Reflexive verbs4.4.1.2. Semantic identity / non-identity of homonym verbs in the active and reflexivevoice4.4.2. Passive voice4.5. Impersonal and unipersonal verbs5. ADVERB5.1. Identifying and forming adverbs5.2. Adverbs with specific morphological functions5.3. Interrogative / relative adverbs5.4. Adverbial structures and phrases5.5. Semantic groups of adverbs5.6. Degrees of comparison of the adverb5.6.1. The comparative degree5.6.1.1. The comparative of superiority5.6.1.2. The comparative of equality5.6.1.3. The comparative of inferiority5.6.2. The superlative degree5.6.2.1. The superlative relative of superiority5.6.2.2. The superlative relative of inferiority5.6.2.3. The superlative absolute5.6.3. Adverbs that do not form degrees of comparison6. PREPOSITION6.1. Basic features of the prepositions6.2. Prepositions and cases6.2.1. Prepositions that require the accusative6.2.2. Prepositions that require the genitive6.2.3. Prepositions that require the dative6.3. Semantic structures with prepositions6.3.1. Various relations created with prepositions6.3.2. The usage of prepositions in structures indicating time and space6.4. Polysemous prepositions7. CONJUNCTION7.1. Basic features of the conjunctions7.2. Conjunctions of coordination7.2.1. The conjunctions şi and iar7.2.2. The conjunctions dar / însă and ci

87.2.3. Correlative conjunctions of coordination7.3. Conjunctions of subordination7.3.1. Conjunctions of subordination used as grammatical markers7.3.2. Semantically specialized conjunctions of subordination7.3.3. Correlative conjunctions of subordination8. INTERJECTION8.1. Basic features of the interjections8.2. Reactive interjections8.3. Communicative interjections8.4. Imitative interjectionsBibliography

90. INTRODUCTION0.1. Romania and the RomaniansRomania (official name România) is an East European country located in the geographic center of the Europeancontinent, on 43 37'07'' and 48 15'06'' north latitude and 20 15'44'' and 29 41'24'' east longitude. The 45th parallel oflatitude north (midway between the Equator and the North Pole) crosses Romania 70 km (43.4 miles) north of thecapital of the country, Bucharest, and the meridian 25 longitude east (midway between the Atlantic coast and theUral Mountains) runs 90 km (55.8 miles) west of Bucharest.Romania borders on the Republic of Moldova to the northeast and east (681.3 km – 422.4 miles), Ukraine to the northand east (649.4 km – 402.6 miles), Bulgaria to the south (631.3 km – 391.4 miles), Serbia to the southwest (546.4 km– 338.7 miles), and Hungary to the west (448 km – 277.7 miles). The total area of the country is 237.5 sq. km (91.699sq. miles).Romania is divided almost equally into mountains (31%), hills and plateaus (36%) and plains (33%). The central areaof the country, the Transylvanian plateau (Podişul Transilvaniei), is surrounded by the Carpathian Mountains (MunţiiCarpaţi), with the highest peak Moldoveanul (2,543 m – 8,341 ft). The mountains slope into hilly regions whichdescend gradually into plains. The natural southern border of Romania is the Danube river (Dunărea). The DanubeDelta (Delta Dunării) is almost entirely on Romanian territory. The length of Romania's Black Sea (Marea Neagră)coast (to the east) is 234 km (145.08 miles).The climate is temperate continental; there are oceanic influences from the west, Mediterranean influences from thesouthwest, and excessive continental influences from the northeast.The government is a constitutional republic with a multiparty parliamentary system and a bicameral Parliament. Thenational flag is composed of three equal vertical stripes: blue, yellow and red (beginning from the flagpole). Thenational seal represents an eagle on a light blue shield, holding a cross in its beak and a sword and scepter in its claws.The coat of arms includes the symbols of the historical provinces – Walachia (Ţara Românească), Moldavia(Moldova), Transylvania (Transilvania), Banat (Banat) and Dobrudja (Dobrogea). The national holiday (since 1990)is December 1, the anniversary of the 1918 union of all Romanians into a single state. The State anthem is a historicpatriotic song composed by Anton Pann, with lyrics by Andrei Mureşanu, "Awake, Ye, Romanian" (Deşteaptă-te,române).The population of Romania is 22.4 million (1999). Most of the inhabitants (89.5) are Romanians, 7.1% areHungarians, 1.7% Gypsies, 0.5% Germans. Other ethnic groups are: Ukrainians, Russians, Serbs, Croats, Turks,Tartars, Slovaks, Bulgarians, Jews, Czechs, Poles, Greeks, Armenians. About 8 million Romanians live abroad. Theurban population represents 55% of the inhabitants.There are 15 religious denominations officially acknowledged in Romania. The most comprehensive are: theRomanian Orthodox Church (86.8%), the Roman Catholic Church (5.0%), the Reformed Church (3.5%), theRomanian Church United with Rome / the Greek-Catholic Church (1.0%), the Pentecostal religion (1.0%), theChristian Baptist religion (0.5%), the Unitarian Church (0.3%), the Seventh-Day Adventist religion (0.3%), theEvangelical Church of Augustan Confession (0.2%), the Muslim religion (0.2%), the Evangelical SynodoPresbyterian Church (0.1%), the Christians of Old Rite (0.1%), and the Mosaic religion (0.1%).The main administrative units in Romania are the county (judeţ), the town (oraş) and the commune (comună). Thereare 41 counties plus the capital city, which has a county status, 262 towns, of which 80 are municipalities, and 2,687communes with 13,285 villages. The capital of Romania is Bucharest, a municipality divided into six administrative

10zones (sectoare), with a population of 2.07 million (1999). Bucharest is located in the Romanian Plain (CâmpiaRomână), along the river Dâmboviţa. Bucharest first appears in a written document in 1459, when it is mentioned asthe city of residence of Vlad the Impaler (Vlad Ţepeş, also known as Dracula). Bucharest became the capital ofRomania in 1862. Other important cities in Romania are: Iaşi (population: 348,000), Constanţa (346,000), ClujNapoca (334,000), Timişoara (333,000), Galaţi (329,000), Braşov (319,000), Craiova (313,000).Romania lies in the East European time zone (GMT 2 hours), in the same time zone as Finland, Greece, Israel,Egypt and the Republic of South Africa. The metric system has been in use since 1866. The national currency inRomania is leu, plural lei, ROL on international markets ( 1 32,000 lei as for February 2004). The domesticconvertibility of the leu was introduced in November 1991.0.2. The Romanian languageThe official language of Romania is Romanian, an Indo-European, neo-Latin language, the easternmost representativeof the family of Romance languages. In terms of sonority, Romanian is very similar to Italian. The Romanianlanguage is the result of the evolution of the Latin spoken in Dacia and Moesia after they were conquered andcolonized by the Roman Empire. The lands north of the Danube, inhabited by Dacians, were conquered in the 2ndcentury, but the territories south of the Danube had already been occupied two centuries before. The populationsliving around the Danube used similar dialects to communicate, and their material and spiritual were very close inmany ways. The Roman colonists spoke the vernacular version of Latin called Vulgar Latin, which differed fromcultivated Latin. The province of Dacia was colonized rapidly, and Latin proved to be strong enough to dissolve andassimilate the native dialects. Rapid Romanization, early Christianity, the day-to-day life that continued in Dacia afterthe withdrawal of the Roman administration in 271 – all these elements prove that the transformation of Latin into anew language began very soon after the Romans started the colonization of the lands of Dacians, when the symbiosisbetween the conquerors and the local population became real. This was a very long process, and it is difficult to statewhen exactly it was completed. Most specialists agree that in the 10th century Romanian as a language with its owndistinctive features was already in use.Over the centuries, the new language experienced numerous external influences, mostly at the lexical level. At thegrammatical level, Romanian is one of the most conservative Romance languages, which is due to the fact that thespeakers belonged to a marginal area, isolated from the rest of the Romance world. Some scholars consider Romanianthe most "pure" Romance language in terms of grammar, i.e. the closest to Latin. However, the nature of thislanguage, especially its vocabulary, has been shaped by various historical influences. Romanian has assimilatedSlavic, Hungarian, Turkish, and neo-Romance elements.The grammatical structure and the basic word stock of the Romanian language have been inherited from Latin. As inall the other Romance languages, in Romanian there is a substratum (i.e. those elements of the native dialects whichwere incorporated into the Vulgar Latin) and a superstratum (i.e. the new elements that penetrated the new Romanianlanguage as a result of the invasions of the migratory peoples). In Romanian, the substratum is Dacian, and thesuperstratum is mostly Slavic. The elements of the substratum are difficult to identify, since there are no reliablesources. The criteria linguists unanimously accept would be the comparison with the Albanian language, consideredto be the direct continuation of the Thracian dialects. Linguists have studied the Romanian language in comparisonwith other Balkan languages, especially Albanian, in an attempt to find words of Dacian origin. Some 160 such wordshave been identified, among them terms related to the human body, family relationships, pastoral activities,agriculture, viticulture, pisciculture, etc.Contacts with the Slavic dialects date back to the 6th or 7th century. The Slavic dialects influenced Romanian, sincethe local population and the newcomers engaged in cohabitation. Two things suggest that when the Slavic elementbegan to influence Romanian, the latter was already a language in its own right. Firstof all, Romanian morphologypreserved almost unaltered its Latin structure. Second, certain phonetic laws typical for Latin did not operate on thenew lexical elements coming from the Slavic superstratum.

11It is important to mention that Romanian did not experience the influence of classical Latin, as other Romancelanguages did. In the Catholic areas (Italy, France, Spain), Latin was the language of culture and religion, whileSlavonic was used in the Orthodox Church and in the administration of the Romanian States. Until the 19th century,Romanian texts were also written in Cyrillic, with adjustments for certain phonetic features of Romanian. It istherefore not surprising that at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century there emerged amongRomanian intellectuals a strong reaction against the Slavic elements present in the language. A process of systematicre-Latinization of Romanian begun, mainly supported by Romanian writers. As a result, a massive amount of termsborrowed from other Romance languages penetrated Romanian. Linguistic research shows that 20% of the Romanianvocabulary is inherited from Latin, 14% are Slavic borrowings (Old Slavic, Bulgarian, Serb, Croatian, Ukrainian,Russian), 2.37% Greek borrowings, 2.17% Hungarian borrowings, 3.7% Turkish, 2.3% Germanic, 38.4% French,2.4% by borrowings from the classic Latin, 1.7% borrowings from Italian. There are many elements in Romanianwhose origin cannot be established precisely. The most intense and active influence in Romanian today, as in otherEuropean and especially East European countries and languages, is that of American English.

121. ALPHABET AND PHONETICS1.1. The Romanian alphabetThe Romanian writing system uses the Latin alphabet, with 5 additional letters formed with diacritics: Ă, ă; â; Î, î; Ş,ş; Ţ, ţ. In reading and writing Romanian, the general rule is that one letter corresponds to one sound. There are,however, some situations in which several letters correspond to one sound, or several sounds to one letter.The letters and their names in Romanian are:A, a (a); Ă, ă (ă); â (â din a); B, b (be), C, c (ce); D, d (de), E, e (e); F, f (fe / ef); G, g (ghe / ge); H, h (ha / haş); I, i(i); Î, î (î din i); J, j (je), K, k (ka de la kilogram), L, l (le / el); M, m (me / em); N, n (ne / en); O, o (o); P, p (pe); R,r, (re / er); S, s (se / es); Ş, ş (şe); T, t (te); Ţ, ţ (ţe); U, u (u); V, v (ve); X, x (ics); Z, z (ze / zet).The letters correspond to sounds as follows :LetterA, aĂ, ăSoundExamples[a]; vowel, central, open, slightly cap head, masă table, palatrounded; similar to a in fatherpalace,magazinstore,pijama pajamas[ ə ]; vowel, central, half-open, măr apple, masă table,pătrat square, capăt end,slightly rounded; similar to a inpăcăleală hoaxabout, or to e(r) in fathervowel,central,close, mână hand, când when,â – this letter does not [y];occur in word-initial unrounded; it is pronounced bătrân old, pâine bread,orword-final somewhat like the sound [ ə ], but cântând singingpositionsfarther back and higher, like asound between i and uB, b[b]; consonant, plosive, bilabial, barcă boat, bine good, bradfir tree, bluză blouse, absolutvoiced; like b in barabsoluteC, c1. when followed bya, ă, â, o, u, orconsonants, or in finalposition2. in the groups che,chi3. in the groups ce, ci[k]; consonant, plosive, velar, cap head, cămaşă shirt,voiceless; like c in carcântec song, corp body,actor actor, acru sour[k’]; consonant, plosive, palatal, chenar border, rachetăvoiceless; like k in keen or kennel rocket,chitarăguitar,achiziţie acquisition[t ]; consonant, affricate, pre- cer sky, a face to do, afacerepalatal, voiceless; like ch in business, cine who, circcircus, aici here, ciorbă sourchartersoup

13D, d[d]; consonant, plosive, dental, da yes, adesea often, adresăvoiced; similar to d in dare, but address, a admira to admire,dental, not alveolaradversar opponent, cândwhen[e] vowel, front, half-open,E, e1. all the positions, unrounded; similar to e in send; inexcept the one below some situations (some personalpronouns and forms of the verba fi to be, inherited from Latin) inword-initial position, it is precededby the semivowel [j]2. pre-vocalic, non- [e] semivowel, front, half-open,syllabicunroundedF, fG, g1. when followed bya, ă, â, o, u, orconsonants, or finalposition2. in the groups ghe,ghi3. in the groups ge, gielefant elephant, bere beer,regulă rule, avere fortune,cerere requesteu I, ei they, este isa bea to drink, a vedea to see,teamă fear[f]; consonant, fricative, labio- far lighthouse, floare flower,dental, voiceless; like f in farafacere business, praf dust[g]; consonant, plosive, velar, gard fence, găină hen, gândvoiced; like g in garment or thought, gură mouth, graddegree, glumă joke, fag beechgradetree[g’]; consonant, plosive, palatal, gheţar glacier, îngheţată icevoiced; like g in get or gift, but cream, ghid guide, ghindămore palatalacorn, unghie finger nail[ dʒ ]; consonant, affricate, pre- gen gender, ager quick, amerge to walk, gin gin,palatal, voiced; like j in jobmagician magician, a fugi torunH, h[h]; consonant, fricative, laryngeal, hainăcloth,hotărârevoiceless; like h in hidecision,hranăfood,autohton nativeI, i1. in initial positionbefore a consonant; inmedial position, infinal position whenstressed and after thegroups cl, cr, dr, str,ştr2. in initial positionbefore a vowel, infinal position after avowel3. in final positionafter consonants, nonsyllabic[i]; vowel, front, close, unrounded; inimă heart, milion million, alonger than the short i in win and iubi to love, a orbi to blind,shorter than the long i in deepmândri proud (m., pl.),albaştri blue (m., pl.)[i]; semi-vowel, front, close, iarnă winter, iepure rabbit, aunrounded; like y in yes or in boy iubi to love, convoi convoy,evantai fan, pui chicken[i]; short semivowel, front, close,unrounded, indicating the palatalor palatalized character of theprevious consonantunchi uncle, albi white (m.,maci poppy flowers,dragi dear (m., pl.), calmicalm (m., pl.), ani years, paşipl.),

14steps, fraţi brothersvowel,central,close, înger angel, întâmplareÎ, î – this letter occurs [y];at the beginning or at unrounded; the same sound as for happening, a coborî tothe end of a word, i.e. âmultîndrăgitdescend,belovedin initial or finalposition, as well as atthe beginning of thesecond component ofa compound wordJ, j[ ʒ ]; consonant, fricative, pre- jad jade, joi Thursday, ajutorhelp, bagaj luggagepalatal, voiced; like s in pleasureK, k – this letter [k], [k’]; consonant, plosive

3.4.3.2. The long form of the reflexive pronouns 3.4.4. Pronouns of reinforcement 3.4.5. Possessive pronouns and pronominal adjectives 3.4.5.1. The possessive pronominal adjectives in the nominative-accusative case 3.4.5.2. The possessive pronouns in the nominative-accusative case 3.4.5.3. The declension of the posse

ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC Folk music is the oldest form of Romanian musical creation, characterized by great vitality; it is the defining source of the cultured musical creation, both religious and lay. Conservation of Romanian folk music has been aided by a large and enduring audience, and

Grammar Express 79 Center Stage 79 Longman Advanced Learners’ Grammar 80 An Introduction to English Grammar 80 Longman Student Grammar of Spoken & Written English 80 Longman Grammar of Spoken & Written English 80 Grammar Correlation Chart KEY BOOK 1 BOOK 2 BOOK 3 BOOK 4 BOOK 5 BOOK 6 8. Grammar.indd 76 27/8/10 09:44:10

IV Grammar/Comp Text ABeka Grammar 10th Grade 5.00 IV Grammar/Comp Text ABeka Grammar 10th Grade 5.00 Grammar/Composition IV ABeka Grammar 10th Grade 3.00 Workbook - Keys ABeka Grammar 12th Grade 10.00 Workbook VI-set ABeka Grammar 12th Grade 20.00 Daily Grams Gra

1.1 Text and grammar 3 1.2 Phonology and grammar 11 1.3 Basic concepts for the study of language 19 1.4 The location of grammar in language; the role of the corpus 31 2 Towards a functional grammar 37 2.1 Towards a grammatical analysis 37 2.2 The lexico-grammar cline 43 2.3 Grammaticalization 46 2.4 Grammar and the corpus 48 2.5 Classes and .

TURKISH GRAMMAR UPDATED ACADEMIC EDITION 2013 3 TURKISH GRAMMAR I FOREWORD The Turkish Grammar book that you have just started reading is quite different from the grammar books that you read in schools. This kind of Grammar is known as tradit ional grammar. The main differenc

Grammar is a part of learning a language. Grammar can be resulted by the process of teaching and learning. Students cannot learn grammar without giving grammar teaching before. Thornbury (1999) clarifies that grammar is a study of language to form sentences. In this respect, grammar has an important role in sentence construction both i.

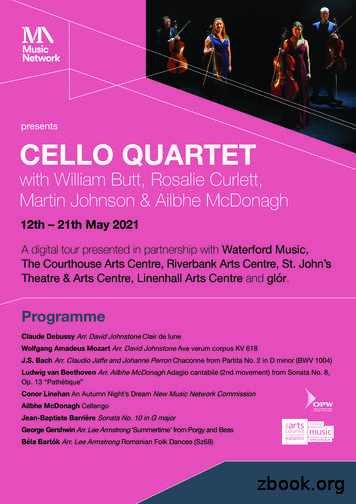

Romanian Folk Dances (Sz68) 1. Jocul cu bâta (Stick dance) 2. Brâul (Sash Dance) 3. Pe loc (Stamping Dance) 4. Buciumeana (Horn (Bucium) Dance) 5. Poarga Româneascã (Romanian Polka) 6. Mãruntel (Fast Dance) Composed for solo piano in 1915 and orchestrated for chamber ensemble in 1917, Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances are based on .

PHONETIC TRAPS FOR ROMANIAN SPEAKERS OF ENGLISH IN MEDICAL COMMUNICATION Patricia SERBAC . chapter about the difficulties of German speakers to pronounce the English interdentals (as the German language also lacks them), but is perfectly valid also for Romanian speakers. PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION AND TRANSLATION STUDIES, 8 / 2015 83