Experts In Patent Cases: Getting The Most Out Of Your Star .

Experts In Patent Cases: Getting The Most Out Of YourStar WitnessBy: Michelle M. Umberger and Christopher G. HanewiczAugust 2013

Michelle Umberger is a partner in the law firm of PerkinsCoie, LLP, where she practices intellectual propertylitigation. She has managed complex, high-stakes casesinvolving a wide range of technologies, including patentsrelating to disk drives, microprocessors, medical devices,antibody libraries, genetically-engineered plants andmechanical devices. She has represented establishedinternational companies, startups, and universities inpatent infringement, false patent marking, trademark,trade dress and unfair competition litigation. Ms.Umberger is a registered patent attorney.Christopher Hanewicz also is a partner in the law firm ofPerkins Coie, and has similarly focused his practice onpatent litigation, managing cases across a wide range ofindustries from sporting goods to disk drives to a methodof genotyping the hepatitis C virus. Mr. Hanewicz hasexperience across all of the major patent dockets,including extensive trial experience in the WesternDistrict of Wisconsin's “rocket docket.” He has gainedsubstantial expertise in managing damages issues tied topatent litigation, and has previously taught CLE courseson how to prosecute and defend lost profits andreasonable royalty cases.

TABLE OF CONTENTSI.Introduction . 1II.Selecting the Right Expert(s) . 1III.A.The Testifying Expert . 2B.Non-Testifying “Supporting” Experts . 5Fed. R. Civ. 26 Rules Governing InteractionsBetween Counsel and Experts . 5A.Testimony From “Non-Experts” . 6B.Cases Interpreting Rule 26(a)(2)(B) & (C). 7C.The Evolution of Expert Discovery . 8D.Cases Interpreting Discoverability UnderRule 26(b) . 12IV.Use of Experts in Claim Construction . 14V.Tools for Limiting or Striking Expert Testimony . 18A.The Federal Circuit’s Recent PrecedentSuggests Additional Avenues for ExcludingExpert Opinion . 19B.How and When to Move to Strike or LimitExpert Testimony . 231.Discrete motion to strike or limittestimony . 23i

C.2.Motion brought as part of summaryjudgment. 233.Motion brought in limineimmediately prior to trial orduring trial . 24A Motion to Strike or Limit ExpertTestimony Must Be Evaluated in Light ofOverall Trial Strategy . 25VI.Potential Safety Valve . 26VII.Conclusion . 27ii

I.IntroductionIn patent cases, as one respected district court judgenoted, “experts and lawyers end up playing the starringroles.” Illumina, Inc. v. Affymetrix, Inc., No. 09-C-277-bbc,2009 WL 3062786, at *2 (W.D. Wis. Sept. 21, 2009).Furthermore, “granting the status of expert cloaks [thatwitness] with some indicia of authority before the jury.” U.S.v. Wen Chyu Liu , 716 F.3d 159, 167 (5th Cir. 2013).Given the attention and weight that will be given tothe testimony of expert witnesses, it is no surprise thatlitigants expend vast resources in selecting, preparing andpresenting expert testimony in patent litigation. This articleis aimed at providing (1) a roadmap for some of the mostimportant issues that arise in the selection and use of bothtestifying and non-testifying experts; (2) an overview of theprovisions concerning discovery of expert work andcommunications; (3) the costs and benefits in using an expertas part of claim construction proceedings; and (4) the toolsavailable to litigants in limiting or striking portions of experttestimony prior to trial, including several recent FederalCircuit decisions that appear to have bolstered the likelyeffectiveness of such tools.II.Selecting the Right Expert(s)There are essentially three types of experts used inpatent infringement litigation: (1) testifying experts; (2) nontestifying experts, whose work/opinions will be relied uponby a testifying expert; and (3) non-testifying/consultingexperts. While the first two points below apply to all typesof experts to varying degrees, this section focuses on thetestifying expert.1

A. The Testifying ExpertConflicts. A threshold issue with all experts is theabsence of conflicts. Career testifying experts will be able torun conflicts checks and alert you to any issues prior toretention. Experts with little or no litigation experience willneed more hand-holding and guidance in this regard. Youwill be required to exercise caution and diligence inuncovering potential conflicts (while avoiding any breachesof confidentiality) and guiding the expert as to how bestresolve issues that are not necessarily disqualifying.1Qualifications in the relevant field of art. Often thefirst use of an expert is to help counsel understand thetechnology at issue. This job may carry over to the judge andultimately the jury. Thus, a preliminary requirement is thatthe potential expert have the knowledge and backgroundnecessary to perform this job. Beyond this, the expert shouldhave a resume that permits testifying at trial as to theparticular technology at issue (i.e., avoid being excludedfrom trial) and, ideally, qualifications in the relevant fieldsuch that the jury is suitably impressed with his or hercredentials—can counsel credibly refer to the expert inclosing as “eminently qualified and recognized in theirfield”?Experience as testifying expert. There may be greatvalue in retaining an expert with experience acting in thisrole in litigation in general and in patent cases in particular.Such experience translates into efficiencies throughout thecase—less time spent explaining the process of litigation and1For a recent discussion of the type of conflict that may disqualify anexpert based on a conflict with the opposing side, and citation to anumber of prior relevant cases, see Return Mail, Inc. v. U.S., 107 Fed.Cl.459, 461 (Fed.Cl.,2012) (denying motion to disqualify expert witness).2

the expert’s role as well as conveying the demands put ontheir time—such as the time it takes to draft an expert report,prepare for deposition, etc. Testifying at trial gives theexpert a comfort level in the courtroom (and can providecounsel with insight from those involved in prior cases as tohow that expert might perform at trial). One can groom anovice expert, but it takes a leap of faith at the time ofretention that the person will morph into the type of expertthat will serve your client well—that the individual will benot only objective and assertive (bringing value to the casethrough careful thought and questioning of the issues), butwill become an advocate for the positions that you ultimatelydevelop together.Presentation skills/personality. Unless your client hasindicated that your particular matter is not going to trial (or itis highly likely to be decided on summary judgment), thelikeability factor is going to come into play with any jury.The jury must be able to understand, and more importantly,believe in your expert. This requires the ability to teach aswell as to inspire confidence. Characteristics to look for: Confidence without arroganceConviction with humilityCredibility (affecting sincerity and certainty ofpositions)RelatabilityAbility to teachAbility to create and relate useful analogies fordifficult technical conceptsAbility to withstand examination/scrutinySense of humorWhile one can name many other personality traits thattend to make a witness appear credible, in the end this3

assessment will come down to the judgment of counsel.Therefore, counsel should be extremely wary of selecting anytestifying expert without an in-person interview, preferablywith more than one trial team member present. Whilephone/video conferences can convey knowledge, experienceand clarity of speech, and recommendations can provideother counsel’s insight into how that witness performed inthe past, only you know the particulars of your case, yourjudge and, most importantly, your jury pool. If you are notfamiliar with the latter, local counsel input should be soughtand their advice carefully considered.In regard to the selection of testifying experts, theideal candidate has both impeccable qualifications in therelevant art and excellent presentation skills. Often times,however, counsel is faced with candidates who are strong inone area, but lacking in the other. While a minimal level ofskill in both categories is a must, the question then becomeswhich is the deciding factor. Many courts allow multipletechnical experts to give opinions on the various liabilityissues that can arise in patent cases, recognizing differentskill sets may come into play and, moreover, that the entiretechnical workload may be too burdensome for oneindividual to carry. In that instance, you may choose toretain two (or more) experts, allocating and dividing issues toplay on the strengths of each—one bringing the charm, theother the ideal technical resume. Counsel can let thecharisma of one expert play to the jury, while simultaneouslybeing able to leverage the detailed analysis and technicalcompetence of the other.In courts where repetition and duplication is strictlypoliced, counsel will need to carefully carve out discretetopics for multiple experts. Even when that is done, somejudges are so strict on efficiency and avoiding cumulativetestimony before the jury that only one technical expert will4

be permitted. In that instance, counsel may face a choicebetween charisma and competence. In that instance, onemust look at the particulars of their case and determine whichfactor has more importance. For example, in a case wherevalidity is strongly challenged, it may be that technicalexpertise is of higher value. An expert discussing whatwould or would not be obvious in the art is open to effectiveattack if that expert was not in the art at the relevant timeperiod or is not intimately familiar with the industry.B. Non-Testifying “Supporting” ExpertsThere may be instances in which the knowledge ofyour “main”/testifying expert needs to be supplemented. Inthat instance, you may choose to use one in the art who canprovide information and, more commonly, perform anytesting that might support the opinions of your testifyingexpert. This supporting expert must have the particulartechnical skill set and means to fill this role and need nothave the presentation skills that one looks for in a testifyingexpert. That said, the supporting expert/consultant must befully competent, diligent and thorough in his or her work. Inaddition, the support experts cannot be meek or overlyhumble—they must have full confidence in their results andopinions as well as the ability to skillfully defend that workin deposition or, potentially, trial. Unlike testifying experts,arrogance is rarely a problem.III.Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 Rules Governing InteractionsBetween Counsel and ExpertsFor cases filed on or after December 1, 2010, newfederal rules regarding expert discovery apply.2 While the2Most courts have considered the new rules to apply to cases pending asof December 1, 2010. However, for cases in the midst of discovery at thetime of transition to the 2010 rules, those courts not applying the new5

new rules have been in place for some – albeit brief – time,an understanding the current rules is aided by looking at howthe Rules were most recently amended.A. Testimony From “Non-Experts”Before discussing the treatment of testifying expertsunder the new rules, a note about individuals who may becalled to testify but have not been specifically retained toprovide expert testimony is in order. For these experts, theproponent of the testimony must disclose to other parties: (i) the subject matter on which the witness isexpected to present evidence under FederalRule of Evidence 702, 703 or 705; and (ii) a summary of the facts and opinions towhich the witness is expected to testify.Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(C).rules outright have handled them in a variety of ways depending upon theparticulars of the case. See CIVIX-DDI, LLC v. Metro. Reg’l Info. Sys.,Inc., No. 2:10cv433, 2011 WL 922611 (E.D. Va. Mar. 8, 2011). Becausethe case had commenced before the December 1, 2010 effective date ofthe Rule 26 amendments, the parties filed a joint motion seeking anexpress ruling that amended Rule 26(b)(4) governed discovery in thecase. The court ruled that since discovery had not commenced until wellafter the effective date of the revision and the parties had ampleremaining time to conduct discovery, application of the amended rule wasjust and practicable. See also Daugherty v. Am. Express Co., No. 3:08CV-48, 2011 WL 1106744 (W.D. Ky. Mar. 23, 2011). The court foundthat it was “just and practicable” to apply the 2010 amendments to Rule26(b)(4) to the case, even though it had commenced in federal court onJanuary 17, 2008 and discovery had been originally set to close onDecember 1, 2010. Thus, documents containing communicationsbetween the expert and Plaintiff’s attorney were privileged. The court didnot provide express reasoning for why application of the revised Rulewas “just and practicable.”6

While this type of “expert” testimony is encounteredfrequently in product liability and personal injury litigation(e.g., in the case of treating physicians or government orinsurance accident investigators), it is less clear when thisrule would apply in patent infringement cases. The mostlikely type of witness in a patent case would be an employeeof the party who will give technical testimony but whose jobis not to give such testimony (i.e., the employee was notretained specifically to give expert testimony).B. Cases Interpreting Rule 26(a)(2)(B) & (C) Chesney v. TN Valley Authority, Nos. 3:09–CV–09,3:09–CV–48, 3:09–CV–54, 3:09–CV–64, 2011 WL2550721 (E.D. Tenn. Jun. 21, 2011).The court denied plaintiff’s motion to excludedefendant’s expert witnesses for failure to provide expertreports as required by Rule 26(a)(2)(B) and/or to providea summary of the facts and opinions to which eachwitness was expected to testify as required by Rule26(a)(2)(C)(ii). Because defendant’s witnesses wereparticipants in the events triggering the litigation, andbecause they were scientists and engineers who had usedtheir “specialized knowledge” in the course of theiremployment duties, they were witnesses for the purposesof Rule 26(a)(2)(C)(ii). Moreover, the disclosuresprovided for each witness, stating the witnesses’ name,position, address and a summary of the expected expertand factual testimony, complied with Rule 26(a)(2)(C). Carrillo v. Lowe’s HIW, Inc., No. 10cv1603–MMA(CAB), 2011 WL 2580666 (S.D. Cal. Jun. 29, 2011).The court ruled that the physicians who treated theplaintiff after an accident on the defendant’s premises,and who he designated as “retained” expert witnesses inhis disclosures, were actually non-retained expert7

witnesses under Rule 26(a)(2)(C). However, because theplaintiff had not provided a summary of the facts andopinions to be presented at trial by the physicians, theirtestimony was limited to that of percipient witnesses andcould not extend to matters beyond the treatment theyrendered to the plaintiff. Graco, Inc. v. PMC Global, Inc., No. 08-1304(FLW), 2011 WL 666056 (D.N.J. Feb. 14, 2011).None of plaintiff’s four “Employee OpinionWitnesses” regularly provided expert testimony as part oftheir job duties and therefore were not subject to Rule26(a)(2)(B)’s requirements. Defendant, however, wasentitled to a disclosure stating the subject matter and asummary of the facts and opinions proffered by theEmployee Opinion Witnesses pursuant to Rule26(a)(2)(C). Downey v. Bob’s Discount Furniture Holdings, 633F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2011).In a footnote, the court noted that although it hadreviewed the lower court’s decision in light of Rule 26(a)as it existed at the time of trial, the December 1, 2010revisions support distinguishing on-the-scene expertsfrom those hired in anticipation of testimony for thepurposes of Rule 26(a)(2).C. The Evolution of Expert DiscoveryThe biggest changes in the Federal Rules in 2010affecting patent experts come in the area of expert discovery.Experts and attorneys no longer have to stipulate aroundobligations to produce draft reports or communicationsbetween experts or take extreme measures to avoid creatingdiscoverable work product (e.g. notes, draft reports8

(protected by Rule 26(b)(4)(B) or communications betweenexperts and attorneys (protected by Rule 26(b)(4)(C))). Thechanges enhance the ability of experts to “collaborate withcounsel to develop and refine theories and opinions.”3 Thenew rules are also intended to save resources by deterringopposing counsel from probing into expert-attorney workproduct, which (for better or worse) means the attorney cantake a more open and active role in drafting expert reports.Below is a summary of the salient areas of change in2010, the former rule, the new rule and the relevant AdvisoryCommittee Notes. In many instances, counsel may befamiliar with this structure as parties in the past have oftenagreed to these types of conditions at the outset of the case,either as part of a joint pretrial statement or protective order.Area ofChangeFormer RuleCurrent �witnessesCreated “atension that []sometimesprompted courtsto require reportsunder Rule26(a)(2)(B) evenfrom witnessesexempted fromthe reportrequirement.”AdvisoryRequiresdisclosure ofsubject matter oftestimony withsummary of factsand opinions.Rule26(a)(2)(C).Mandates that asummary of thefacts and opinionsto be presented attrial by any nonretained expertmust bedisclosed, but afull expert reportis not required.“This disclosureis considerably3Patrice Schiano & Thomas E. Hilton, Comments of the AmericanInstitute of Certified Public Accountants on Proposed Amendments toRule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Feb. 17, 2009, at ocuments/FRCPFinal.pdf.4See Fed. R. Civ. P. 26, Adv. Committee’s Notes (2010).9

Area ofChangeFormer RuleCurrent RuleCommittee Notes.Drafts ofreportsThe old rule wasthat, absent theparties’agreement to thecontrary, alldrafts shared withcounsel weresubject todiscovery.Communications withcounselCommunicationsbetween expertsand counsel werediscoverable.10AdvisoryCommitteeNotes4less extensivethan the reportrequired by Rule26(a)(2)(B).”Drafts of reportsor disclosuresfrom testifyingexperts are nolonger subject todiscoveryregardless of theform in whichthe draft regardless of theform of thecommunications,subject to threeexceptions: (i)compensation;(ii) facts or datathe expertconsidered informingopinions; and(iii)communicationsthat identifyassumptionsDiscovery“regarding draftexpert reports ordisclosures, ispermitted only inlimitedcircumstancesand by courtorder.”“The addition ofRule 26(b)(4)(c)is designed toprotect counsel’swork product andensure thatlawyers mayinteract withretained expertswithout fear ofexposing thosecommunicationsto searchingdiscovery.”

Area ofChangeFormer RuleCurrent RuleAdvisoryCommitteeNotes4relied upon byexpert.Rule26(b)(4)(C).Informationconsidered byexpert witnessExperts wererequired todisclose all “dataor otherinformation”considered.Experts arerequired todisclose only“facts or dataconsidered.”Rule26(a)(2)(B)(ii).“The refocus ofdisclosure on‘facts or data’ ismeant to limitdisclosure tomaterials of afactual nature byexcludingtheories or mentalimpressions ofcounsel. At thesame ti

value in retaining an expert with experience acting in this role in litigation in general and in patent cases in particular. . 459, 461 (Fed.Cl.,2012) (denying motion to disqualify expert witness). 3 the expert’s role as well as conveying the demands put on their time—such as the time it takes to draft an expert report,

Australian Patent No. 692929 Australian Patent No. 708311 Australian Patent No. 709987 Australian Patent No. 710420 Australian Patent No. 711699 Australian Patent No. 712238 Australian Patent No. 728154 Australian Patent No. 731197 PATENTED NO. EP0752134 PATENTED NO.

Patent-Mapper, which maps the location of patents within the U.S., given a selected patent application year, patent state, and patent class. . Along with the patent, the Longitude and the Latitude will also be provided for geolocation purposes. Other information such as invent

TECHNICAL INFORMATION PLEXIGLAS Solid sheet, block, multi-skin sheet, corrugated sheet, tube and rod . Patent EP 530 617 3 Europ. Patent EP 548 822 4 Europ. Patent EP 149 182 5 Europ. Patent EP 733 754 6 Europ. Patent EP 776 931 7 Europ. Patent EP 600 332. PLEXIGLAS Ref. No. 211-1 02/2 Page 4/7

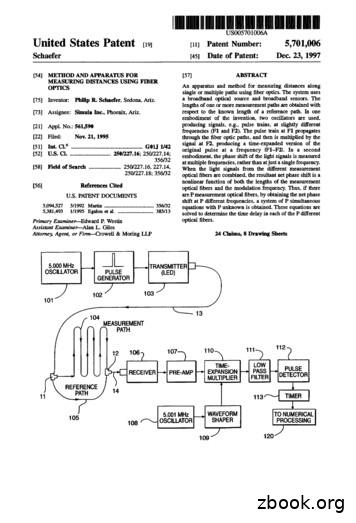

United States Patent [191 Schaefer US00570 1 006A Patent Number: 5,701,006 Dec. 23, 1997 [11] [45] Date of Patent: METHOD AND APPARATUS FOR MEASURING DISTANCES USING FIBER

US007039530B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.:US 7 9 039 9 530 B2 Bailey et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 2, 2006 (Us) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Asslgnee. ' . Ashcroft Inc., Stratford, CT (US) EP EP 0 1 621 059 462 516 A2 A1 10/1994 12/2000

USOO6039279A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 6,039,279 Datcuk, Jr. et al. (45) Date of Patent: Mar. 21, 2000 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS

Book indicating when the patent was listed PTAB manually identified biologic patents as any patent potentially covering a Purple Book-listed product and any non-Orange Book-listed patent directed to treating a disease or condition The litigation referenced in this study is limited to litigation that the parties to a

No. 2. Frost, The Patent System and the Modern Economy (1956). No. 3. Patent Office, Distribution of Patents Issued to Corporations, 1939-1955 (1956). No, 4. Federico, Opposition and Revocation Proceedings in Patent Cases (1957). No. 5. Vernon. The International Patent System and Foreign Policy (1957). No. 6. Palmer, Patents and Nonprofit .