Independent Review Of Gross Negligence Manslaughter And .

Independentreview of grossnegligencemanslaughterand culpablehomicideJune 2019Working together for a just culture

Independentreview of grossnegligencemanslaughterand culpablehomicide

Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicideContentsForeword by Leslie Hamilton, Chair of the Review3Executive summary5Chapter 1About the independent review9Terms of referenceWhat we did and who we heard from1012Chapter 2 Gross Negligence Manslaughter and Culpable Homicide 14Chapter 3 The roots of concern19A pyramid effectRebuilding the GMC’s relationship with the professionChapter 4 Cross-cutting issues202123The experience of patients and their familiesEquality, diversity and inclusion issuesThe environment of medical practiceSystemic failures, corporate accountability and embedding a just cultureMedical expert evidenceChapter 5 Processes leading up to a criminal investigationLocal investigationsSupport for staffThe investigators242729323540414242Chapter 6 Investigations by coroners or procurators fiscalRole of the coroner and the coroner serviceCrown Office and Procurator Fiscal ServiceVariation between coroner jurisdictionsGNM guidance for coronersGuidance and support for doctors involved in the coronial processSupport for the family through the processDissemination of learningOther issues considered1454646474749505152

Chapter 7 Police investigations and decisions to prosecute53Application of the law in the medical contextAgreed statement on the lawPolice investigations: training, guidance and support for SeniorInvestigating OfficersProcess of decision making and scrutiny5455Chapter 8 The GMC555759Regulator appealsPublic confidence in the medical professionClinical error and the criminal lawClinical error and medical regulationTimeliness and reformReflective practiceSupport for doctorsChapter 9 Conclusion and evaluationList of RecommendationsRebuilding the GMC’s relationship with the professionFamilies and healthcare staffEquality, Diversity and InclusionSystem scrutiny and assuranceExpert reports and expert witnessesLocal Investigations into patient safety incidentsCoroner service in England and WalesPreparedness for Coroner and Procurators Fiscal proceedingsPolice, Crown Prosecution Service and Procurators FiscalGMC policies and processesReflective practiceSupport for doctorsIndependent Review of GNM/CH 77777

Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicideForewordThis independent review, commissioned by the General Medical Council (GMC),has its origins in the tragic death of a child and the subsequent conviction forgross negligence manslaughter (GNM) of the senior paediatric trainee involvedin his care.The decision of the GMC to seek this doctor’s erasure from the medical registerfollowing her criminal conviction caused consternation and outrage across largesections of the medical profession in the United Kingdom (UK) and overseas.Some described it as a ‘toxic fear’. Many questioned why an individual traineeworking under pressure should carry the blame for what they considered to bewider systemic failings within her working environment. They recognised hersituation in their own working lives and felt that ‘there but for the grace ofGod, go I.’The criminal conviction and the actions of the GMC provided the immediatefocus for doctors’ fears and sense of injustice, but this was part of a morefundamental loss of confidence in the GMC and in the operation of a fair andjust culture in medicine. In the minds of many doctors, the fear begins whenthings go wrong in the workplace and with the belief that the ‘system’is structured to apportion individual blame rather than to learn from eventsand prevent future harm. It continues through coronial inquests, criminalinvestigation and the regulatory process which, some doctors feel, does notsufficiently recognise the realities of medical practice. In England and Wales,it is not necessary to be wilfully reckless or intend harm to become the focusof a criminal investigation. This adds to the sense of vulnerability felt by aprofession dedicated to caring for its patients. The blame culture can be realenough, but perceptions about vulnerability to criminal investigation are notalways well founded. Out of approximately 250,000 licensed doctors in theUK, the number likely to be brought into these processes is extremely small,although any criminal prosecution will come at the end of a much longer chainof investigations which inevitably takes its toll on the individual doctor. But thefact the perceptions exist at all is symptomatic of the embattlement felt by manyin the profession. Such an atmosphere does not serve the interests of doctorsor, more importantly, their patients.3

ForewordThe healthcare services have woken to the need for just and fair treatmentof staff, but the practical application of the principles has so far been patchy,at best. The public also recognises the pressures under which healthcareprofessionals labour to care for them and that recklessness or deliberateharm are extremely rare and need to be viewed differently from unintendedfailings. But they also, rightly, expect candour and action when their lovedones have come to harm. Doctors are trusted to care for their patients tothe highest possible standards, so bad doctors cannot be shielded. To meetthese expectations, personal and system accountability must be balancedwith learning and prevention of future harm. But local, coronial, judicialand regulatory processes operate independently and are directed atachieving different goals. Criminal justice and a just culture do not seek thesame outcome.In this report we aim to shine a light on how the system currently operatesand how it is seen by those working within it. We make recommendationsaimed at the better application of a just and fair culture when things go wrong.Ultimately, that is what is best for patients.Leslie HamiltonChair of the Independent Review of Gross Negligence Manslaughterand Culpable Homicide4

Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicideExecutive summary1 Over the last year there has been much discussion about the importance of a justand fair culture in medicine and the need to learn, not blame, when things go wrong*.Fundamentally, this report is about how to achieve that aim, for the benefit of bothpatients and the doctors who care for them.*2 or some, realising a just culture means changing the law surrounding gross negligenceFmanslaughter (GNM) and culpable homicide (CH). That was not within the remitor competence of this review. Instead, our focus has been on how the systems,procedures and processes surrounding the criminal law and medical regulation areapplied in practice and how they can be improved to support a more just and fairculture. In doing so, we have listened carefully to all those who have a part to play. Wehave heard from doctors and doctors’ organisations, patients and their families, patientorganisations, lawyers, academics, coroners, healthcare service providers, regulatorsand many others. We have also examined the approach taken in the different countriesof the UK. In Scotland, where the law relating to CH is different from the law on GNMwhich applies in the rest of the UK, we have not identified any convictions of a doctorfor culpable homicide linked to the discharge of their medical duties. Indeed, many ofthe concerns reported to us do not seem to arise in the Scottish context.3 lthough the criminal investigation and prosecution of doctors is extremely rare, theAeffect of just one case has been palpable and profound across the medical profession.Many doctors feel unfairly vulnerable to criminal and regulatory proceedings shouldthey make a mistake which leads to a patient being harmed. The depth of this feelinghas resulted in a breakdown in the relationship between many doctors and theirregulator, the GMC. The GMC must take urgent steps to repair that relationship so thatit is better able to work with and support doctors in delivering a high standard of carefor their patients [Recommendations 1-2].4 ut the decisions of a regulator when things go wrong are only the final stage of aBcomplex series of processes which begin with the healthcare service provider andwhich may stretch over many years. Those processes often do not serve the needsof doctors or patients and their families. Although all four countries of the UK havedeveloped robust frameworks to enable good quality, fair and just investigationof incidents, they are inconsistently applied, poorly understood and inadequatelyresourced [Recommendations 15-16]. Not only doctors, but also patients and theirfamilies can feel unsupported and excluded from these processes just-culture5

Executive summary5 S ome groups of doctors feel particularly at risk. Although the statistical data is limited,research evidence points clearly to the increased risk for Black, Asian and MinorityEthnic (BAME) doctors being referred into regulatory proceedings and the dangers ofprofessional isolation and lack of support. This is an issue for healthcare services andregulators alike to address [Recommendations 5-9].6 T he vulnerability felt by many doctors reflects their sense of working in healthcareservices that are under considerable strain and where individuals trying to do theirbest for their patients can too easily be blamed for mistakes arising from wider systemfailures. Although many doctors told us that these pressures were not sufficientlyunderstood by the wider public, the evidence we heard suggests that the publicare, in fact, acutely aware of the challenges faced by those caring for them. Evenso, healthcare service providers have a responsibility for the environments in whichdoctors practise and when things go wrong to the extent that a doctor faces criminalinvestigation, the appropriate external authorities should scrutinise the systems withinthe department where the doctor worked. This is particularly relevant where the doctorinvolved is a trainee [Recommendation 10].7 nce an investigation is underway, much reliance will be placed on the opinions ofOthose who are commissioned to provide medical expert evidence about the actionsof the doctor or doctors involved. Invariably, it is other doctors who provide theseexpert opinions. We heard repeated concerns about how those who put themselvesforward as experts are selected, how their opinions are calibrated and how their workis quality assured. The weight of concern expressed to us points to a widespreadlack of confidence in a system which relies on the confidence placed in experts[Recommendations 11-14].8 The lack of consistency seen in the quality of local healthcare service providerinvestigations is mirrored in the processes of the coroner service in England and Wales.The local nature of the coroner service, coupled with the rarity of potential GNM cases,means it is difficult for individual coroners to develop experience in handling such casesand knowing when the police should be notified. The Chief Coroner and his Deputieshave a role in supporting greater consistency of decision making [Recommendation17]. These are not issues we encountered when looking at the system in Scotland.9 octors appearing at coroners’ courts also need better support. Although inquisitorialDin nature, the process can feel adversarial and accusatory. Healthcare service providershave a responsibility to provide support and guidance for doctors involved in theseprocesses so that they are better prepared [Recommendation 18].6

Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicide10 T he rarity of potential GNM and CH cases is also an issue for the police. The police areunder close scrutiny and pressure to investigate fully whenever there are allegations ofserious criminal conduct in a healthcare setting. Investigating officers should have earlyaccess to independent medical advice to inform their understanding of what is allegedto have taken place. Responsible Officers are well placed to co-ordinate the provisionof suitable independent advice for the police in the initial stages of an investigation[Recommendation 19]. This will give the police greater confidence over whether a fullinvestigation is required and families’ confidence in the independence of the advice givento the police.11 L ack of confidence in organisations and processes is a theme which pervaded much of theevidence we heard. Sometimes this reflected individuals’ perceptions rather than facts;families perceptions that doctors and healthcare service providers wish to conceal thetruth of wrong-doing; doctors’ perceptions that they are regarded as guilty until proveninnocent. Sometimes perceptions can be well founded. At other times they are not.For example, we heard of doctors’ belief that the CPS recruits experts who will supportthe case for prosecution rather than provide a balanced view on the doctor’s conduct.Whether or not perceptions are well-founded in fact, they are powerful in influencingbehaviours. Greater transparency is needed to aid understanding about how decisions aremade and improve confidence in the integrity of key processes [Recommendation 20].12 D octors’ loss of confidence in the GMC was at the heart of this review. Our final suiteof recommendations is aimed at helping the GMC to tackle this issue so as to supportbetter and fairer regulation. To that end we have recommended that the GMC examinethe processes which contributed to doctors’ loss of confidence. We also support theUK Government’s plan to remove the GMC’s power to appeal decisions of the MedicalPractitioners Tribunal Service [Recommendation 21].13 The GMC regulates doctors on behalf of society and has a statutory duty to regulate so asto promote and maintain public confidence in the medical profession. We commissionedindependent research to help us better understand public expectations, particularlywhere a doctor has been convicted of a criminal offence. The results of that research arecomplex and nuanced, and point both to an understanding of the pressures under whichdoctors work, but also an expectation of accountability when patients are harmed. Thereis work for the GMC to do to improve understanding of its role and its responsibility notto punish doctors for past mistakes but to ensure their ongoing fitness to practise. TheGMC and Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service must consider how this is reflected intheir guidance to tribunals [Recommendations 22-23]. There is also work for the UKGovernment in bringing forward planned legislative reform that will enable the GMC totake a more proportionate approach to its handling of concerns about doctors’ fitness topractise [Recommendations 24-25].7

Executive summary14 B ut even with legislation that is fit for purpose, some of the changes that are neededcannot be delivered by the GMC alone. There is much that doctors can do to helpthemselves. This includes using the tools that have been developed to help themengage in reflective practice in a way which will support their learning and limit theirperceived vulnerability to the misuse of their reflective notes in other proceedings[Recommendation 26]. Doctors’ professional bodies, medical defence organisations,healthcare service providers and others should work with the GMC to explore howdoctors under investigation can be better supported [Recommendation 27]. Healthcareservice providers can do more to provide induction and support for those doctors whoare new to medical practice or returning to clinical practice after a significant absence[Recommendation 28].15 T he recommendations contained in this report are directed at a number of differentorganisations. Although these are independent bodies, we hope they will recognise theneed for change to enhance public and professional confidence in the processes overwhich they preside. As the GMC commissioned our review, we also hope that the GMCwill monitor the adoption and implementation of our proposals [Recommendation 29].8

Chapter 1About theindependentreview

Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicideChapter 1: About the independent review16 The independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicide (GNM/CH) was commissioned by the GMC in January 2018. The Chair of the review and theworking group that has taken forward the review are independent of the GMC, althoughthe GMC has provided the secretariat.* The members of the group were appointed bythe Chair† for the range of knowledge, experience and perspectives they personallycould bring to the issues. They were not selected to represent the views of particularorganisations or interest groups. Their task has been to bring a truly independent analysisof the evidence collected during the review and to report their findings. This report setsout their conclusions and recommendations. The members of the working group, andtheir biographies, are listed on the review webpages.17 T he law in Scotland relating to culpable homicide (CH) is different from the law onGNM which applies in the rest of the UK. A separate Scotland task and finish group wastherefore set up to advise the main working group on the issues as they applied in theScottish legal and healthcare context. The members of the task and finish group are listedon the review webpages. Its report to the working group setting out its advice is also onthese webpages.Terms of reference18 Our terms of reference are set out on the review webpages.19 The decision to commission the review followed widespread concern among the medicalprofession about the treatment of Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba (a graduate of Leicester medicalschool and a senior trainee paediatrician) who was convicted of GNM and subsequentlyerased from the medical register in 2018. The focus of that concern was the GMC’sappeal against the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS) decision to suspendrather than erase Dr Bawa-Garba from the medical register. Mid-way through this review,the Court of Appeal overturned the High Court’s decision to erase Dr Bawa-Garba fromthe medical register and reinstated her suspension. Although Dr Bawa-Garba’s caseprovided the catalyst for this review, we have not considered the details or merits ofthat case or other cases where doctors have been convicted of GNM. Rather, we haveexamined the broader issues raised by those cases in which serious incidents leadingto patient deaths are brought into the criminal and the regulatory arena and the widersystem in which they occur.* A number of steps were taken to ensure the independence of the working group and the review. Working group memberswere identified and appointed by the review Chair. The written evidence collated by the secretariat to assist the group wasreviewed both through sampling by members of the working group and by independent audit. In addition, when drawing up itsconclusions and recommendations the working group initially met separately from the secretariat.† Dame Clare Marx was initially appointed to lead the review in January 2018. In July 2018 she was appointed by the PrivyCouncil as the next Chair of the GMC. She immediately stood down as Chair of the review to avoid any conflict of interest. Shewas succeeded as Chair of the review by Mr Leslie Hamilton who was already a member of the working group.10

Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicide20 Our review had its origins in doctors’ concerns about their perceived vulnerabilityto criminal prosecution for GNM/CH as a result of medical mistakes, and the risk ofregulatory action by the GMC. But it was also a review about patients, their families andprotecting the public when things have gone wrong

The environment of medical practice 29 Systemic failures, corporate accountability and embedding a just culture 32 . Independent Review of GNM/CH evaluation 77 2. This independent review, commissioned by the General Medical Council (GMC), . In this report we aim to shine a light on how the system currently operates

d. Supreme Court 4 3. Alternative Dispute Resolution (“ADR”) 4 4. Kentucky’s Rules of Civil Procedure 5 5. Local Rules 5 B. The Kentucky Federal Court System 5 Negligence 5 A. General Negligence Principles 5 B. Gross Negligence: Willful and Wanton Conduct 7 C. Burden-Shifting Approach 8 D. Attractive Nuisance 9

The class-actionsuit brings claims for negligence or gross negligence, breach . answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, designate specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial. . (quoting Parker v. Hartford Fire Ins. Co., 278 S.E.2d 803, 804 (Va. 1981)). Thus, underVirginia law, the questionofwhetherthe insurer .

SERIES 6.25 gross torque * (190cc) 675-700 SERIES 6.75, 7.00 ft-lbs gross torque* (190cc) PROFESSIONAL SERIES 8.75 ft-lbs gross torque * (190cc) 7.75 ft-lbs gross torque * (175cc) * All power levels are stated gross torque per SAE J1940 as rated by Briggs & Stratto STARTING EASE Aft

Gas consumption is calculated using a calorific value of 38.7 MJ/m 3 (1038 Btu/ft) gross or 34.9 MJ/m3 (935 Btu/ft3) nett To obtain the gas consumption at a different calorific value: a. For l/s- divide the gross heat input (kW) by the gross C.V. of the gas (MJ/m3) b. For ft3/h - divide the gross heat input (Btu/ h) by the gross C.V. of the gas .

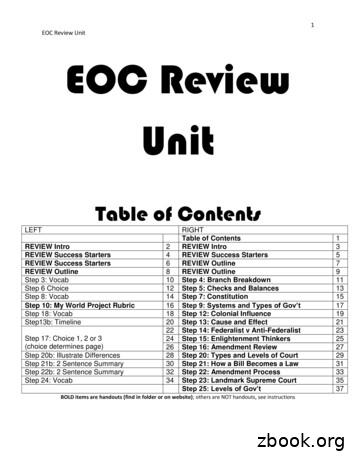

1 EOC Review Unit EOC Review Unit Table of Contents LEFT RIGHT Table of Contents 1 REVIEW Intro 2 REVIEW Intro 3 REVIEW Success Starters 4 REVIEW Success Starters 5 REVIEW Success Starters 6 REVIEW Outline 7 REVIEW Outline 8 REVIEW Outline 9 Step 3: Vocab 10 Step 4: Branch Breakdown 11 Step 6 Choice 12 Step 5: Checks and Balances 13 Step 8: Vocab 14 Step 7: Constitution 15

Under the common-law doctrine of negligence, the burden of proof was on the employee, as plaintiff, to prove that the employer was negligent by failing to provide “due care” to prevent the injury and that this negligence was the proximate cause of the injury, illness, or death.

Connecticut Variable Only for actions that do not sound in negligence. CONN. GEN. STAT. § 52-572h(c) (2018). Delaware Pure Joint and Several Defendants are jointly and severally liable. Exception: Recovery is barred when a plaintiff is more than 50 percent at fault and if defendant’s conduct was plain negligence. 10 DEL. CODE § 6301

The American Revolution had both long-term origins and short-term causes. In this section, we will look broadly at some of the long-term political, intellectual, cultural, and economic developments in the eigh-teenth century that set the context for the crisis of the 1760s and 1770s. Between the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the middle of the eigh- teenth century, Britain had largely failed .