Consumption Tax Trends 2008: VAT/GST And Excite Rates, Trends And .

Consumption Tax Trends 2008Consumption Tax Trends2008VAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and AdministrationIssuesVAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and Administration IssuesThe full text of this book is available on line via this e with access to all OECD books on line should use this link:www.sourceoecd.org/9789264039476SourceOECD is the OECD online library of books, periodicals and statistical databases.For more information about this award-winning service and free trials ask your librarian, or write to usat SourceOECD@oecd.org.www.oecd.org/publishingisbn 978-92-64-03947-623 2008 14 1 PVAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trendsand Administration IssuesConsumption Tax Trends 2008In this publication, the reader can find information about Value Added Tax/Goods and Services Tax(VAT/GST) and excise duty rates in OECD member countries. It provides information about indirecttax topics such as international aspects of VAT/GST developments in OECD member countriesas well as in selected non-OECD economies. It describes a range of taxation provisions in OECDcountries, such as the taxation of motor vehicles, tobacco and alcoholic beverages. This edition’sspecial feature describes the way VAT is implemented in three significant non-OECD economies:China, Russia and India.-:HSTCQE UX Y\[:

Consumption Tax Trends2008VAT/GST AND EXCISE RATES, TRENDSAND ADMINISTRATION ISSUES

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATIONAND DEVELOPMENTThe OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together toaddress the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also atthe forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments andconcerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of anageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policyexperiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinatedomestic and international policies.The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic,Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea,Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic,Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The Commission ofthe European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD.OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the Organisation’s statistics gathering andresearch on economic, social and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines andstandards agreed by its members.This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. Theopinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the officialviews of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries.Also available in French under the title:Tendances des impôts sur la consommationTVA/TPS EN DROITS D’ACCISE : TAUX, TENDANCES ET QUESTIONS D’ADMINISTRATIONCorrigenda to OECD publications may be found on line at: www.oecd.org/publishing/corrigenda. OECD 2008You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimediaproducts in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as sourceand copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to rights@oecd.org. Requests forpermission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC)at info@copyright.com or the Centre français d'exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) contact@cfcopies.com.

FOREWORDForewordThis publication is the seventh in the series Consumption Tax Trends. It presents informationrelative to indirect taxes in OECD member countries, as at 1 January 2007.This biennial publication illustrates the evolution of consumption taxes as revenue instruments.They now account for 30% of total tax revenues in OECD member countries. It identifies the largenumber of differences that exist in respect of the consumption tax base, rates and implementationrules while highlighting the features underlying their development. It also notes recent developmentsin the Value Added Tax/Goods and Services Tax area, including international issues on taxation ofservices and intangibles under general consumption taxes.This edition’s special feature highlights aspects of VAT/GST developments in China, India andRussia.This publication was prepared by Stéphane Buydens of the OECD Centre for Tax Policy andAdministration, in co-operation with governments of OECD member countries that provided mostdata in the tables. It is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General.CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 20083

TABLE OF CONTENTSTable of ContentsIntroduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7Consumption Tax Trends – English Summary 2008 Edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9Tendances des impôts sur la consommation – Résumé en français – Édition 2008 . . . . .15Chapter 1. Taxing Consumption . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21Chapter 2. Consumption Tax Topics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31Chapter 3. Value Added Taxes Yield, Rates and Structure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39Chapter 4. Selected Excise Duties in OECD Member Countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .73Chapter 5. Taxing Vehicles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .87Chapter 6. Application of Value Added Taxes in three Non-OECD Economies:China, Russia and India. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105Annex 1.Exchange rates PPP 2006 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117Annex 2.Countries with VAT (2008) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118List of 1.3.12.3.13.3.14.4.1.4.2.Taxes on general consumption (5110) as percentage of GDP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxes on general consumption (5110) as percentage of total taxation . . . . . . . .Taxes on specific goods and services (5120) as percentage of GDP . . . . . . . . . . .Taxes on specific goods and services (5120) as percentage of total taxation . . . . .Value added taxes (5111) as percentage of GDP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Value added taxes (5111) as percentage of total taxation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Revenue shares of major taxes in the OECD area (unweighted average) . . . . . .VAT/GST rates in OECD member countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Annual turnover concessions for VAT/GST registration/collection . . . . . . . . . .VAT/GST Exemptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Coverage of different VAT/GST rates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Special VAT/GST taxation methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Import/export of goods by individuals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .VAT Revenue Ratio (VRR) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxation of beer. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxation of wine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . axation of alcoholic beverages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxation of mineral oils . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxation of tobacco . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxes on sale and registration of motor vehicles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79818390CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 20085

TABLE OF CONTENTS5.2.5.3.6.1.6.2.Taxes on use of motor vehicles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95Taxes on sale and registration of selected new vehicles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100VAT rates in China . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107VAT rebates for exports – China – (examples – non-exhaustive list) . . . . . . . . . 108List of Figures1.1.3.1.3.2.5.1.Average tax revenue as a percentage of aggregate taxation, by category of tax. . .Share of consumption taxes as percentage of total taxation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Standard rates of VAT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Taxes on sale and registration of new cars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22474799This book has.StatLinks2A service that delivers Excel filesfrom the printed page!Look for the StatLinks at the bottom right-hand corner of the tables or graphs in this book.To download the matching Excel spreadsheet, just type the link into your Internet browser,starting with the http://dx.doi.org prefix.If you’re reading the PDF e-book edition, and your PC is connected to the Internet, simplyclick on the link. You’ll find StatLinks appearing in more OECD books.6CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 2008

INTRODUCTIONIntroductionConsumption taxes form an important source of revenue for an increasing number ofgovernments. They now account for 31% of all revenue collected by governments acrossthe OECD. Value added taxes* (VAT) are the principal form of taxing consumption in 29 ofthe 30 OECD member countries (the United States continues to deploy retail sales taxes)and account for two thirds of consumption taxes revenues. The remaining third is made upof specific consumption taxes such as excise duties.This trend probably reflects a growing preference for broad based taxation of the fullrange of goods and services, as opposed to taxing specific goods. Increasingly excise is usedas a means of influencing consumer behaviour, with many countries imposing high ratesof excise on tobacco goods and alcohol.Value added tax policyThe continuing globalisation of trade imposes an increasing pressure on the internationalaspects of value added tax systems, at the same time as these systems have spread across theworld. Differences between value added tax systems operated by individual countries creategrowing difficulties for both businesses and tax administrations. The absence ofinternationally agreed rules and standards for the treatment of cross-border supplies reducesthe capacity of governments to collect taxes and creates uncertainties for businesses. Currentinconsistencies in the VAT rules across jurisdictions can hinder the development ofinternational trade, generating uncertainties, double taxation or involuntary non-taxation aswell as opening up opportunities for tax avoidance (OECD 2004).A public consultation launched by the OECD in 2005 showed general support for aninternational norm based on taxation according to the rules applicable in the jurisdictionof consumption. It was agreed therefore that the OECD should develop a set of guidelinesthat would aim to minimise the problems identified. In January 2006 the OECD launched aproject aimed at providing guidance for governments on applying value added taxes tocross-border trade: the OECD International VAT/GST Guidelines, which includes the workalready done on applying VAT/GST to e-commerce.In the long run, these Guidelines should encompass a wide span of issues relating tothe application of value added taxes to cross-border trade, including determination of theplace of taxation, valuation of transactions, avoidance of double taxation and compliance.However, the OECD considers that the first priority is to deal with the application of valueadded taxes to cross-border trade in services and intangibles, since this appears to be themost pressing issue for both business and tax administrations. Guidelines are beingdeveloped to ensure that each cross-border transaction is taxed in only one jurisdiction. In*This concept includes value added taxes (also called goods and services taxes) but does not coversales taxes.CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 20087

INTRODUCTIONparallel, since value added taxes should be borne, in principle, by final consumers,Guidelines will also be developed to ensure that the burden of the value added taxesthemselves do not lie on taxable businesses, except where explicitly provided for inlegislation. In other words, taxation should not result from inconsistencies betweenlegislations but from their fair application.These Guidelines are being developed by OECD governments, together with input fromboth business and from non-OECD economies. The process includes the publication ofconsultation documents on the OECD website (www.oecd.org/tax).Excise taxes and vehicle taxationAs in previous editions, Consumption Tax Trends reports on the excise taxes thatmember countries levy on a number of specific products, including alcoholic beverages,mineral oil products and tobacco products. It also provides a detailed survey of vehicletaxes.Value added taxes in selected non-OECD economiesThis edition provides an overview on the implementation of value added tax systemsin selected non-OECD economies China, India and Russia.Consumption tax statisticsSelected tables from this edition of Consumption Tax Trends are updated annually inthe OECD tax database and may be consulted at the following address: www.oecd.org/ctp/taxdatabase.BibliographyOECD (2004), Report on Consumption Tax Obstacles to Cross-border Trade in International Services andIntangibles, OECD, Paris.OECD (2005), The Application of Consumption Taxes to the International Trade in Services and Intangibles,OECD, Paris.OECD (2006), International VAT/GST Guidelines, OECD, Paris.8CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 2008

ENGLISH SUMMARYEnglish SummaryChapter 1 – Taxing ConsumptionThe importance of consumption taxesConsumption taxes include, on the one hand general consumption taxes, typically valueadded taxes (VAT and its equivalent, sometimes called Goods and Services Tax – GST) andretail sales taxes and on the other hand taxes on specific goods and services, consistingprimarily of excise taxes, customs duties and certain special taxes.Looking at the unweighted average of revenue from both these categories of taxes as apercentage of overall taxation in the OECD member countries (see Table 3.2, Table 3.3 and 3.7),it can be seen that the proportion is roughly 31%. In 2006, this broke down to one-third fortaxes on specific goods and services and two-thirds for general consumption taxes.The value added taxVAT is the most widespread general consumption tax in the world since it has now beenimplemented by over 140 countries and in 29 of the 30 OECD member countries (the UnitedStates continues to deploy retail sales taxes). The value added tax system is based on taxcollection in a staged process, with successive taxpayers entitled to deduct input tax onpurchases and account for output tax on sales in such a way that the tax finally collected by taxauthorities equals the VAT paid by the final consumer to the last vendor. These characteristicsensure the neutrality of the tax, whatever the nature of the product, the structure of thedistribution chain and the technical means used for its delivery. When the destinationprinciple, which is the international norm, is applied, it allows the tax to retain its neutrality incross-border trade. According to this principle, exports are exempt with refund of input taxes(“zero-rated”) and imports are taxed on the same basis and with the same rates as localproduction.The application of the destination principle is relatively easy for the cross-border trade ingoods but not always so for services due to their normally intangible nature. Since it is not easyto assess their place of effective consumption, and hence of taxation, most countries havedeveloped a range of proxies. Within the European Union, those proxies are based on the placewhere the supplier or the customer are established. However, different criteria may be appliede.g. in Australia and New Zealand. Although those different systems attempt to reach a similargoal (taxing consumption where it occurs) their application can give rise to differences oftreatment for cross-border supplies and create areas for potential double taxation, involuntarynon-taxation and uncertainties for business and tax administrations.Consumption taxes on specific goods and services: excise taxesExcise taxes differ from VAT since they are levied on a limited range of products; are notnormally liable to tax until the goods enter free circulation and are generally assessed byCONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 20089

ENGLISH SUMMARYreference to the weight, volume, strength or quantity of the product, combined in some cases,with ad valorem taxes. As with VAT, excise taxes aim to be neutral internationally since they arenormally collected once, in the country of final consumption.Chapter 2 – Consumption Tax TopicsAs the use of VAT was spreading as an efficient means to taxing consumption, theinternational trade in goods and services expanded rapidly. As a result, the interactionbetween value added tax systems operated by individual countries has come under greaterscrutiny as the potential for double and unintentional non-taxation has increased.The first international VAT rules (beyond the European Union) were adopted in 1998 withthe Ottawa Taxation Framework Conditions and provided that “rules for the consumptiontaxation of cross-border trade should result in taxation in the jurisdiction where consumptiontakes place”. As a result, the OECD’s Committee on Fiscal Affairs (CFA) adopted the Guidelineson Consumption Taxation of Cross-Border Services and Intangible Property in the Context of Ecommerce in 2001. These Guidelines indicate that the place of consumption is deemed to be inthe jurisdiction in which the recipient has established its business presence (for business-tobusiness transactions) or its usual place of residence (for business-to-consumer transactions).Further to the development of globalisation and cross-border trade, it became clear that moreglobal rules were necessary beyond electronic commerce. In 2005 the CFA adopted aframework for the development of the OECD International VAT/GST Guidelines. As a first step,it was agreed that the most pressing issue was the definition of the place of taxation for crossborder trade in services and intangibles and the conditions for the neutrality of the tax. In 2006the CFA approved the two following basic principles: for consumption tax purposes internationally traded services and intangibles should betaxed according to the rules of the jurisdiction of consumption; the burden of value added taxes themselves should not lie on taxable businesses exceptwhere explicitly provided for in legislation.These principles are currently being developed by OECD governments, together withinput from business and from non-OECD economies. This work is subject to a publicconsultation process and working papers are available on the OECD website (www.oecd.org/tax).Additional work is undertaken on improving the efficiency of tax administration, the fightagainst VAT fraud and tax administration issues.Chapter 3 – Value Added Tax: Yield, Rates and StructureThere are many differences in the way VAT systems are implemented across countries.This is illustrated by the continued existence of a wide range of lower rates, exemptions andspecial arrangements that are frequently designed for non-tax policy objectives. Whilecountries’ tax sovereignty remains essential, a number of shared basic principles are needed inorder to guarantee a measure of coherence that can help prevent double taxation, involuntarynon-taxation, tax evasion and distortion of competition. A number of factors also allow forimproving the efficiency of the tax such as a broad base; minimal exemptions and reducedrates; and a registration threshold that allows a tax administration to concentrate on moresignificant taxpayers.Tables 3.1 to 3.7 show that the importance of general consumption taxes variesconsiderably between countries, from the United States and Japan where general consumptiontaxes account for less than 10 per cent of total taxation and less than 3 per cent of GDP, to10CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 2008

ENGLISH SUMMARYHungary and Iceland where they account for more than 26 per cent of total tax and more than9 per cent of GDP. In the majority of countries, general consumption taxes account for morethan 15 per cent of total taxation.The revenue from taxes on general consumption, mainly in the form of VAT receipts,stabilised after 2000 following a period of many years in which it gradually increased. Over thelonger term, OECD member countries have relied increasingly on taxes on generalconsumption to the detriment of taxes on specific goods and services, the total ofconsumption taxes remaining stable over the last 30 years at around 30% of total tax revenues.Tables 3.8 to 3.11 illustrate the wide diversity in tax rates, exemptions and taxationthresholds. Standard VAT rates (Table 3.8) have remained generally stable since 2000 althoughsome trends in various directions can be observed. Five countries have decreased theirstandard rate (Canada, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary and the Slovak Republic) whileseven countries increased the rate (Germany, Greece, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal,Switzerland and Turkey). It may be worth noting that eight of the twelve countries that havechanged their standard rate are getting closer to 19%, either by increasing or decreasing theirrate.Given this diversity, it is reasonable to consider the influence of these features on therevenue performance of VAT systems. One tool considered as an appropriate indicator of sucha performance is the VAT Revenue Ratio (VRR), which is defined as the ratio between the actualVAT revenue collected and the revenue that would theoretically be raised if VAT was applied atthe standard rate to all final consumption (Table 3.14). In theory, the closer the VAT system ofa country is to the “pure” VAT regime (i.e. where all consumption is taxed at a uniform rate), themore its VRR is close to 1. On the other hand a low VRR can indicate a reduction of the tax basedue to large exemptions or reduced rates or a failure to collect all tax due (e.g. tax fraud).Chapter 4 – Selected excise duties in OECD member countriesExcise duty, unlike VAT and general consumption taxes, is levied only on specificallydefined goods. The three principal product groups that remain liable to excise duties in allOECD countries, are alcoholic beverages, mineral oils and tobacco products. While exciseduties raise substantial revenue for governments, they are also used to influence customerbehaviour with a view in particular to reducing polluting emissions or consumption ofproducts harmful for health such as tobacco and alcohol.While the main characteristics and objectives ascribed to excise duties are approximatelythe same across OECD countries, their implementation, especially in respect to tax rates,sometimes gives rise to significant differences between countries (Tables 4.1 to 4.5). Forexample, excise duties on wine (Table 4.2) may vary from zero (Austria, Italy, Luxemburg,Portugal, Spain and Switzerland) to more than USD 3.5 a litre (Iceland, Norway and Turkey).Current excise rates for mineral oil products again illustrate the wide disparity. For example,excise taxes on premium unleaded gasoline vary from USD 0.105 in the United States to USD1.747 in Turkey for 1 litre. A much more significant feature of excise duties on mineral oils isthe fact that duty rates have been used to affect consumer behaviour to a greater degree thanin other areas. Tobacco products are submitted to excise taxes that most often rely on acombination of ad valorem and specific elements.CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 200811

ENGLISH SUMMARYChapter 5 – Taxing VehiclesMotoring has been an important source of tax revenue for a long time thanks to a widerange of taxes imposed on users of public roads. Vehicle taxation in its widest definitionrepresents a prime example of the use of the whole spectrum of consumption taxes. Thesetaxes include taxes on sale and registration of vehicles (Tables 5.1 and 5.3); periodic taxespayable in connection with the ownership or use of the vehicles (Table 5.2); taxes on fuel(Table 4.4) and other taxes and charges, such as insurance taxes, road tolls etc. Increasingly,these taxes are adjusted to influence consumer behaviour in favour of the environment.Table 5.3 illustrates, for example, the wide differences in the level of taxes on sale andregistration of motor vehicles. Indeed, for a standard passenger car, these taxes may vary fromless than 7% of the value of the car in Washington DC to 200% of the value of the car inCopenhagen.Chapter 6 – Application of Value Added Taxes in Three Non-OECD Countries:China, Russia and IndiaVAT in ChinaChina implemented VAT in 1984. Since the 1994 tax reform, it applies to most suppliesand importation of goods and to services directly relating to those supplies. The Chinese VATsystem is based on the standard staged collection process (see Chapter 1). Globally the systemis based on the destination principle where exports are zero rated and imports are taxed on thesame basis and with the same rates as local production. It includes a standard rate of 17% anda reduced rate of 13% (see Table 6.1). In 2007, the revenue from VAT accounted for 34% of thetotal tax revenues.However, the Chinese VAT system deviates from the international standards in three keyareas. Firstly, VAT applies to supply and importation of movable goods and specific servicesdirectly relating to those goods, such as processing and repairs while most services andsupplies of immovable property, including construction, are not subject to VAT. These suppliesare subject to a Business Tax (BT) of 5%, which accrues to local governments. Secondly, VAT onfixed assets is non-deductible. Thirdly, limits are placed on the rebate of input tax credits asthey relate to exports. Exports then incur a part of residual VAT. Rebates vary according to thenature of the exported products (Table 6.2). For example, the rebate rate for high technologyproducts is 17% (which is equal to a full input tax credit since the standard VAT rate is 17%)while there is no rebate for polluting products. The Chinese government undertook a VATreform in 2004 with a view to allow for a full input tax credit on fixed assets in pilot regions.This reform is likely to be extended to the whole country in 2009.VAT in RussiaThe Value Added Tax was adopted by the Soviet Union in December 1991 upon the eve ofits dissolution. Further to a number of tax reforms, which took place as part of the shift from acentrally planned economy to a decentralised market economy, the Russian Tax Code has beenredrafted several times in the last fifteen years. Since the 2006 reform, the Russian VAT systemis now close to the European model, with a staged collection process (see Chapter 1) and thedestination principle for cross-border trade. Taxable supplies include supply of goods, servicesand works made on Russian territory (with some usual exemptions such as financial servicesand health care). The tax code provides for three VAT rates: the standard rate of 18%, a reducedrate of 10% and a zero rate. However, the Russian VAT system deviates from the international12CONSUMPTION TAX TRENDS 2008 – ISBN 978-92-64-03947-6 – OECD 2008

ENGLISH SUMMARYstandards in two key areas. Firstly, supplies of services, goods and works made outside Russiaare considered outside the scope of Russian VAT. This means that, unlike in the standard VATmodel, input VAT in relation to those supplies is not deductible. This means that e.g. a Russiantaxpayer that provides advertising services only to foreign clients has no right to deduction ofinput VAT incurred in Russia. Secondly, the origin principle is applied to exports of oil and gassupplies within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). These exports are taxedunder Russian VAT at the standard rate of 18%.VAT in IndiaA VAT system was introduced in India in 2005. However, according to the federal structureof the country, in which exclusive tax powers are assigned by the Constitution to each layer ofgovernment (Union, States and local authorities), the tax base was shared among theseentities. VAT on trade in goods is levied by the States while VAT on services is levied by theCentral Government. Each State has developed its own VAT legislation based on a commonmodel, close to the international standards (staged collection process with full right todeduction of input tax). The Central Government also has fixed uniform VAT rates: 12.5%(standard rate); 4% (reduced rate applicable to most items

VAT/GST And ExCiSE RATES, TREndS And AdminiSTRATion iSSuES Consumption Tax Trends 2008 VAT/GST And ExCiSE RATES, TREndS And AdminiSTRATion iSSuES In this publication, the reader can find information about Value Added Tax/Goods and Services Tax .

VAT ( ) C VAT EU Tax Authorities * Electronic Interface EU , VAT EU-established Intermediary (Tax Representative) . Tax Representative VAT Return VAT EU Tax Authorities VAT & IOSS No. Commercial Invoice Data DHL IOSS EU Tax Authorities VAT Return VAT 10

1. VAT inclusive A The VAT received by a business from sales of goods or income earned. 2. VAT vendor B Payments which are made twice in a month. 3. Input tax C VAT is excluded in the marked price. 4. VAT invoice D Receipts issued by SARS for VAT payments. 5. VAT exclusive E VAT is payable when the

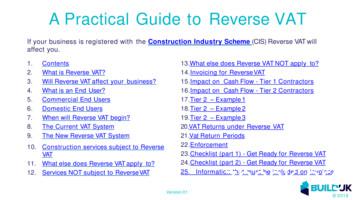

A Practical Guide to Reverse VAT 1. Contents 2. What is Reverse VAT? 3. Will Reverse VAT affect your business? 4. What is an End User? 5. Commercial End Users 6. Domestic End Users 7. When will Reverse VAT begin? 8. The Current VAT System 9. The New Reverse VAT System 10. Construction services subject to Reverse VAT 11. What else does Reverse VAT apply to? 12. Services NOT subject to .

In general, the VAT due equals output VAT less input VAT. As a rule, input VAT may be deducted from output VAT when a taxpayer receives an invoice for goods or services purchased, or in the two subsequent VAT reporting periods. However, to deduct input VAT the

total for the tax or VAT. The purpose of the VAT fields at the header level is to store the overall total tax or VAT amounts represented on the invoice image. Assuming the VAT rate is identical for all line items, the system will auto-distribute the VAT to the gross amount for each li

VAT, or Value Added Tax, is a tax that is charged on most goods and services that VAT registered businesses provide in South Africa. Unlike other taxes, VAT is collected on behalf of SARS by registered businesses. Once you’re registered for VAT, you must charge the applicable rate of VAT

Costs deduction 4. Capital tax 4.1. Wealth tax 4.2. Real estate tax 5. Gift Tax and Inheritance Tax 5.1. Taxable base 5.2. Personal allowances 5.3. Relief of double taxation 6. VAT 6.1. VAT system 6.2. Dutch VAT rates 6.3. Small business regulation 6.4. Import VAT deferral . The withholding agent withholds

Albert Woodfox a, quant à lui, vu sa condamnation annulée trois fois : en 1992, 2008, et . février 2013. Pourtant, il reste maintenu en prison, à l’isolement. En 1992 et 2013, la décision était motivée par la discrimination dans la sélection des membres du jury. En 2008, la Cour concluait qu’il avait été privé de son droit de bénéficier de l’assistance adéquate d’un .