2006-2007 Weed Management Handbook - University Of Wyoming

Go to Introduction

Cover Photo: Roemeria poppy (Roemeria refracta) invading northern Utah wheat/fallowcropland.Montana State University, Utah State University and the University of Wyoming are affirmative action/equal opportunity employers and educational organizations. We offer our programs to persons regardless of race, color, nationalorigin, gender, religion, age, or disability. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 andJune 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Montana, Utah and Wyoming CooperativeExtension Services at Bozeman, MT; Logan, UT; and Laramie, WY.Trade or brand names used in this publication are used only for the purpose of educational information. The information given herein is supplied with the understanding that no discrimination is intended, and no endorsement informationof products by the Agricultural Research Service, Federal Extension Service, or State Cooperative Extension Service isimplied. Nor does it imply approval of products to the exclusion of others which may also be suitable.

WEEDMANAGEMENTHANDBOOK2006-2007Montana Utah Wyoming

ContentsAUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORSINTRODUCTION . iHERBICIDES AND THEIR PROPERTIES . 1Section I - Herbicide-Resistant Weeds . 1Section II - Sprayer Calibration . 8Section III - Approximate Retail Prices of Selcted Herbicides . 16Section IV - Conversion Tables . 17Section V - Worker Protection Standard for Agricultural Pesticides . 19Section VI - Web Resources for Weed Science . 27AGRONOMIC WEED CONTROLAlfalfa . 28Canola . 43Corn and Sorghum . 48Dry Beans . 72Peas and Lentils . 79Grasses for Seed . 89Potatoes . 102Proso Millet . 114Safflower . 118Small Grain Crops - Wheat, Barley, Oats, Fallow . 124Sugarbeets . 166Sunflowers . 176AQUATIC AND DITCHBANK WEED CONTROL . 181PASTURE AND RANGELAND WEED MANAGEMENT . 192NONCROP SITES/RIGHTS-OF-WAY . 205CONTROL OF PROBLEM WEEDS AND POISONOUS PLANTS . 227INDEX . 248GLOSSARY . G-1

WeedManagementHandbook2001-2002Montana Utah WyomingEditors/AuthorsSteven A. DeweyUtah State UniversityExtension Weed Specialist(435) 797-2256Stephen D. MillerUniversity of WyomingAssoc. Dir., Ag. Exp. Station(307) 766-3667Stephen F. EnloeUniversity of WyomingExtension Weed Specialist(307) 766-3113Ralph E. WhitesidesUtah State UniversityExtension Weed Specialist(435) 797-8252Fabian D. MenalledMontana State UniversityExtension Weed Specialist(406) 994-4783Lori JohnsonUtah State UniversityExtension Staff Assistant(435) 797-2255ContutingAuthontrribibuthorrsWilliam E. Dyer-Montana State University, Professor of Weed ScienceMark A. Ferrell-University of Wyoming, Pesticide SpecialistRuth Richards-Utah State University, Research Assistant

INTRODUCTIONPurpose: This handbook is designed as a quick and ready reference of weed control practices used in variouscropping systems or sites/situations in Utah, Montana and Wyoming. Because chemical regulation of plantgrowth is complex and requires considerable knowledge, a large portion of the handbook is devoted toregistered uses of herbicides, crop desiccants, and some plant growth regulators. In all cases, authors havemade every effort to list only registered herbicides and to ensure that the information conforms with productlabels and company recommendations.Intended Users: The handbook may be useful to producers, company field representatives, commercialspray applicators, consultants, and herbicide dealers. The editor of each section is listed. Feel free to call themor your state weed Extension specialist, if you have questions.Revision and Availability: The handbook is revised every 2 years and is available from the Bulletin rooms atMontana State University (406-994-3273), Utah State University (435-797-2251) and the University ofWyoming (307-766-2115).Caution!The information provided in this handbook is not intended to be acomplete guide to herbicide use.Before using any chemical, you should thoroughly read the label. The recommendation on the manufacturerslabel, when followed, can prevent many problems arising from incorrect use of a chemical.This information is supplied with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement isimplied by the University Cooperative Extension Service. Trade names (brand names) are used in this handbook.The authors have assembled the most reliable information available to them at time of publication. Due toconstantly changing laws and regulations, the authors assume no liability for the recommendations. Any use ofa pesticide contrary to instructions on the label is not legal or recommended.Weed Management Suggestions Weed PreventionWeed prevention means a land manager prevents the introduction of weed seed or vegetative propagules ontothe land. This requires vigilance and the ability to identify weed seeds, seedlings, and mature plants. After aweed is introduced to a piece of land WEED ERADICATION is nearly impossible, and the endless processof WEED MANAGEMENT begins.One of the most important aspects of weed management is the development of a multi-tactic program tocontrol weeds. This approach, known as Integrated Weed Management (IWM), reduces the chances ofa weed to adapt to any particular control technique. For example, the increased reliance in herbicides with thesame mode of action has resulted in weeds that are resistant to those herbicides (see Section IV. HerbicideResistant Weeds). Also, the continuous production of certain crops provides weeds a chance to adapt to theparticular environment associated with that crop. IWM takes advantage of cultural, mechanical and chemicali

weed control strategies in the best possible way with the goal of maintaining weed densities at manageablelevels while preventing shifts in weed populations to more difficult-to-control weeds.Combining as many of the following practices as possible will allow you to design an IWM program: Avoid weed establishment; eliminate individual survivors.Establish competitive crops that will “choke out” weeds.Identify and map weed infestations.Keep records over years.Recognize and eliminate new weeds before they multiply and establish.Control vegetation and seed sources around the field or site.Comply with or become involved in establishing county/state weed laws and noxious weed controlprograms.Employ sanitary procedures; prevent weed spread: Clean equipment between sites or infestations. Examine nursery plants, seed, and imported soil or media. Use Certified Seed. Screen irrigation water that comes from surface storage through canals.Cultural Practices of an IWM ProgramCrop Rotation, defined as the alternation of different crops in a systematic sequence on the same land, is oneof the most important components of an IWM program. Weeds thrive in crops having similar environmentalrequirements as their own. Moreover, management practices designed to benefits certain crops may alsobenefit the growth of specific weeds. For example, winter annual weeds such as downy brome or jointedgoatgrass are commonly found in winter wheat fields as they share similar environmental requirements. Croprotation helps managing weeds because the different environmental conditions created by different crops withina rotation disrupt weed germination and growth cycles. Also, the wide variety of management options associatedwith each crop (tillage, planting dates, herbicide rotation, etc.) creates multiple stresses on weeds.Know the weed spectrum in a field then select the crops according to their ability to compete with thoseweeds. Rotate crops to disrupt weed life cycles or suppress weeds in a competitive crop before planting a lesscompetitive crop.Plant competitive crops instead of fallowing to improve soils and weed management. Research with Indianheadlentils and other annual legumes appears to be promising fallow substitutes. Also, alfalfa reduces the ability ofannual weeds to grow, however it favors growth of perennial weeds. Sudangrass, perennial grasses and tamebuckwheat, grown in dense stands, provide intense competition against weeds. Consider legumes to supplement soil nitrogen requirements.Consider specific varieties of cereals with natural plant toxins (allelopathy); vegetation must remainuniform on the soil surface; either perennial or large-seeded crops can be planted through undisturbedmulch.Consider crops such as oats or spring barley that winter kill after vigorous fall growth. This avoids orreduces the need for controls the following spring.Alter planting dates to encourage maximum early crop growth or delay planting until the first flush of weedsis controlled.ii

Modify placement and time of application of fertilizer, especially nitrogen. Band or spot fertilizer below crop seed to reduce its availability to surface-germinating weeds.Time the application of fertilizer using side-dressing for maximum crop growth or to minimize weeddevelopment.Develop crop canopy to shade weeds and suppress weed germination. Select crops or varieties that form a canopy quickly.Space plants in equidistant (triangular) arrangements and vary density depending on crop managementconstraints or harvest requirements.Interplant crops in space and time (consider mechanical limitations in commercial plantings).Manage an appropriate living mulch (grass or legume) between perennial crop rows.Improve pasture management by reseeding and/or fertilizing to reduce weed infestation (weeds areusually a symptom of poor management).Apply Mulch Organic mulches such as straw may reduce available N when decomposing, but it could be infestedwith weed seed.Sawdust can be used but you must avoid vertebrate pests by maintaining a mulch-free circle aroundtrees. Also, perennial weeds can become a serious problem under mulch.Use bark mulch, black plastic or landscaping fabric which excludes light and therefore controls mostannual weeds.Avoid clear plastic mulch because it acts like a greenhouse and produces poor weed control.There are wavelength-selective plastics that can help in weed and pest management.Mechanical Weed ControlMechanical weed control involves the physical destruction of a weed. Techniques involve HAND PULLINGor HAND HOEING which are practical for small infestations. MOWING is often used; but by far, the mostcommon practice of mechanical control includes TILLAGE. Advantages of tillage include: Elimination of weed debrisControll of annual weedsSuppression of perennial weedsTillage methods include plowing, rototilling, disking, and harrowing. Weed control implements includesweeps, rolling cultivators, finger weeders, push hoes, rotary hoes, etc.Other Cultural Methods of Weed ControlFlaming is a technique that can be useful but it requires a physical difference or separation between crops andweeds, or crop protection with a hooded row cover or protein foaming agents.Proper water management, such as the use of drip irrigation or uniform irrigation, can eliminate certainweeds.iii

Stale seedbeds involve a delay in planting after seedbed preparation to control the first flush of weeds beforeseeding.Biological Weed ControlBiological control involves the use of natural enemies, such as predators, parasitoids, competitors, or pathogensto control pest insects, weeds, or diseases to levels lower than they would otherwise be. There are three mainmethods of biological control: conservation, introduction, or augmentation. Human activities can greatly influencethe extent to which natural enemies are able to suppress pests. Conservation Biological Control is definedas any biological control practice designed to protect and maintain populations of existing natural enemies.This approach is particularly useful in agroecosystems where management practices such as cultivation, pesticideapplications, and harvest disrupt the life cycle of the beneficial organisms. Introduction or Classical BiologicalControl refers to the importation of foreign natural enemies to control previously introduced, or native, pests.Finally, Augmentation Biological Control involves control practices intended to increase the number oreffectiveness of existing natural enemies. This approach is commonly used in cases where natural enemies aremissing (greenhouses) or late to arrive at new plantings (some row crops), or simply too scarce to providecontrol.Many of our worst weeds originated in foreign countries and biological control practices can help us to maintainthem below threshold levels. These newly introduced plants, free from the natural enemies found in theirhomelands, gained a competitive advantage over native plants. Once they are out of control, other methods ofweed management are usually not economical or physically possible. The need for a method of weed reductionthat was economical, self-sustaining, and environmentally safe provides opportunities for biological control.There are several well-documented successes of biological control: St. Johnswort (Klamathweed in California),tansy ragwort in Oregon, and rush skeletonweed in the Pacific Northwest.Biological control is a slow process, and its efficacy is highly variable. It usually takes several years for abiological control agent to become established and control a weed. Biological control agents impact weeds intwo ways: directly and indirectly. Direct impact destroys vital plant tissues and functions. Indirect impactincreases stress on the weeds, which may reduce their ability to compete with desirable plants. Thus, it is veryuseful to integrate biological control with other weed management practices. For example, once weeds areweakened by Biological Control Agents, competitive plantings may be used to outcompete the weeds.The goal of a biological control program is not to eradicate a pest, but to maintain it below an acceptablethreshold level. When using BCAs, a residual level of the weed populations must be expected since thesurvival of the agents is dependent on the density of their host weeds. After populations of the host weedsdecrease, populations of BCAs will correspondingly decrease. This is a natural cycle and should be expected.The BCAs released in the U.S. have been thoroughly tested to ensure they are host-specific. This is anexpensive and time-consuming task that must be done before the agents are allowed to be introduced. Anextensive assessment of BCAs prior to their release secures they will not switch to crops, native flora, andendangered plant species.Biological control of certain weeds may not work in your area, even though an insect may be very effective inanother area. Climate variations such as cold winters, and plant biotype differences may account for some ofthe failures that have occurred in the past. To ensure maximum success, trained personnel must supervisebiological control programs. Biological control agents are living entities and require specific conditions tosurvive.iv

As with any other weed management method, biological control has benefits and disadvantages. The benefitsinclude: reduction of herbicide residues in the environment, host specificity on target weeds, long-term selfperpetuating control, low cost per acre, searching ability to locate hosts, synchronization of agents to life cyclesof hosts, and unlikelihood that hosts will develop resistance to agents. Some of the disadvantages of biologicalcontrol include: the limited availability of agents from their native homelands, the dependence of control onplant density, the slow rate at which control occurs, biotype matching, and host specificity when host populationsare low.v

Table 1.WeedBrown knapweedBull thistleCanada thistleThe current status of biological weed control agents released in eitherMontana, Utah, and/or WyomingAgentUrophora quadrifasciataUrophora stylataCeutorhynchus lituraOrellia ruficaudaRhinocyllus conicusUrophora carduiDalmatian toadflaxCalophasia lunulaDiffuse knapweedBangasternus faustiLarinus minutusPterolonche inspersaSphenoptera jugoslavicaUrophora affinisUrophora quadrifasciataAgapeta zoeganaGorseAgonopterix nervosaExapion ulicisItalian thistleCheilosia corydonRhinocyllus conicusLeafy spurgeAphthona cyparissiaeAphthona czwalinaeAphthona flavaAphthona lacertosaAphthona nigriscutisSpurgia esuleaMeadow knapweed Urophora quadrifasciataMediterranean sage Phrydiuchus tauMilk thistleRhinocyllus conicusMusk thistleCheilosia corydonRhinocyllus conicusTrichosirocalus horridusPlumeless thistleRhinocyllus conicusTrichosirocalus horridusPoison hemlockAgonopterix alstroemerianaPuncturevineMicrolarinus lareyniiMicrolarinus lypriformisPurple loosestrifeGalerucella calmariensisGalerucella pusillaHylobius transversovittatusRush skeletonweed Cystiphora schmidtiEriophyes chondrillaePuccinia chondrillinaRussian knapweed Subanguina picridisSt. JohnswortAgrilus hypericiAplocera plagiataChrysolina hypericiChrysolina quadrigeminaZeuxidiplosis giardiScotch broomAgonopterix nervosaApion fuscirostreLeucoptera spartifoliellaSlenderflower thistle Rhinocyllus conicusDistributionMT UT WYULL LWW WLF LWULLU LLLU UWL LWL LUL ULL LLU LWL LU LWL WLU LLWW WLU WUL FL FLU LU ULL LLLWWLU-viInfestationMT UT WYULLMLLLSSLUUUULUUUUM LMM M MUSULSLLULM SLULM SHLUMUHHHSUMUUUUUUUULSSM UM M M-ControlMT UT WYUUU FPF UUUFUUUU UUUU UGU UGU UUU UUU UUU UGU UU UEU UUU UPGG GUU GUU U UU UU UUU UGUGGU-AvailabilityMT UT WY- - OLO L- M L LL- OL- OO- OO OO- LO OM O OM O OOO O- - - - LO OLO OLO OO OM O MLO O- - - O- M M MLO L- - O- O O OO OO O- - - - OO OL- O- L- L- O- - - - - -

Table 1.The current status of biological weed control agents released in eitherMontana, Utah, and/or Wyoming - continuedWeedSpotted knapweedAgentAgapeta zoeganaBangasternus faustiChaetorellia acrolophiCyphocleonus achatesLarinus minutusLarinus obtususMetzneria paucipunctellaTerellia virensUrophora affinisUrophora quadrifasciataSquarrose knapweed Urophora affinisUrophora quadrifasciataAgapeta zoeganaBangasternus faustiSphenopter jugoslavicaTansy ragwortLongitarsus jacobaeaePegohylemyia seneciellaTyria jacobaeaeYellow starthistleBangasternus orientalisChaetorellia australisEustenopus villosusLarinus curtusUrophora sirunasevaYellow toadflaxBrachypterolus pulicariusCalophasia lunulaGymaetron antirrhiniDistributionMT UT WYWULLLLWUUULULLLWULWSLLLUUUULUUUUWWUInfestationMT UT WYMUUUUUMUUUUUSUUHUMHSMSLUUUUSUUUULMUControlMT UT T UT WYLOOOOOLOOOOOOOOMOOMOOOOOOOOOOOOOLLODistribution within host range: W widespread, L limited sites, F failed to establish, U unknown status, - not yet releasedInfestation of hosts: H heavy ( 70%), M medium ( 30%), L light ( 10%), S - slight (. 1%), O none detected, U unkown statusAbility to control seed production and/or plant density: E excellent, G good, F fair, P poor, U underterminedAvailability for redistribution: M mass collection, *L limited, O not collectable at present*Limited availability indicates agent populations are slow in building or recently introduced. Information concerning these species can beobtained through biological control specialists at the state department of agriculture or state university in your state. Collection and/ortransportation of biological control agents may require special permits and procedures.vii

Table 2.The biological weed control agents released, the general role of eachagent, and the type of introduction (C classical and A accidental).Spe cie sRoleSpe cie sRoleAgapet a zoeganaroot boring moth CGymnaet ron ant irrhiniseed head weevil AAgonopt erixalst roemerianadefoliating moth AHylobius t ransv ersov it t at usroot boring weevil CAgonot opt erix nerv osashoot tip moth ALarinus curt usseed head weevil CAgrilus hypericiroot boring beetle CLarinus minut usseed head weevil CAplocera plagiat adefoliating moth CLarinus obt ususseed head weevil CApht hona cyparissiaeroot/defoliating flea beetle CLeucopt era spart if oliellatwig mining moth AApht hona czwalinaeroot/defoliating flea beelte CLongnit arsus j acobaeaeroot/defoliating flea beetle CApht hona f lav aroot/defoliating flea beetle CMet zneria paucipunct ellaseed head moth CApht hona lacert osaroot/defoliating flea beetle CMicrolarinus lareyniiseed weevil CApht hona nigriscut isroot/defoliating flea beetle CMicrolarinus lyprif ormisstem boring weevil CApion f uscirost reseed weevil COrellia ruf icaudaseed head fly ABangast ernus f aust iseed head weevil CPegohylemyis seneciellaseed head fly CBangast ernus orient alisseed head weevil CPhrydiuchus t aucrown/root weevil CBrachypt erolus pulicariusflower beetle APt erolonche inspersaroot boring moth CCalophasia lunuladefoliating moth CPuccinia chondrillinarust fungus CCeut orhynchus lit uracrown/root weevil CRhinocyllus conicusseed head weevil CChaet orellia acrolophiseed head fly CSphenopt era j ugoslav icaroot boring/gall beetle CChaet orellia aust ralisseed head fly CSpurgia esulaeshoot tip gall midge CCheilosia corydoncrown/root fly CSubanguina picridisstem/leaf gall nematode CChysolina hypericidefoliating beetle CTerellia v irensseed head lly CChrysolina quadrigeminadefoliating beetle CTrichosirocalus horridusroot/crown weevil CCyphocleonus achat esroot boring/gall weevil CTyria j acobaeaedefoliating moth CCyt isphora schmidt istem/leaf gall midge CUrophora af f inisseed head gall fly CEriophyes chondrillaebud gall mite CUrophora carduistem gall fly CEust enopus v illosusseed head weevil CUrophora quadrif asciat aseed head gall fly AEx apion ulicisseed weevil CUrophora sirunasev aseed head gall fly CGalerucella calmariensisleaf beetle CUrophora st ylat aseed head gall fly CGalerucella pusillaleaf beetle CZeux idiplosis giardileaf fall midgeviii

Year-Round Weed Management Strategies: A SummaryWeed PreventionEmploy sanitary practices. Prevent new weed infestations. Prevent weed shifts resulting from repeated: Cultivation (enhances perennial weeds). Mowing (enhances prostrate weeds). Herbicides (enhances tolerant weeds, new weed biotypes, new microorganisms that render herbicidesinactive).Identify and Map Your Weeds Recognize weeds with identification books (annuals, biennials, perennials).Map and record infestations (weed abundance).Keep yearly records.Prioritize Your Weeds by Developing Priorities Highly competitive weeds (control them).Moderately competitive weeds (suppress them).Noncompetitive weeds (don’t worry about them).List the Control Methods Gained from: Your experience.Local experts.Published information.Learn the strengths and weaknesses of each control method.Design a Weed Management ProgramSelect a field or area with manageable weed problems. Consider the environmental aspects. Consider the erosion potential. Consider surrounding water, high-value vegetation, or urban and/or recreational areas. Consider costs, equipment, management skills, precision timing, and other factors needed to achieveresults. Develop year-round weed management strategies involving combinations of weed control practices.Evaluate Your Results Evaluate weed management programs.Continue mapping weeds for future reference.Modify practices as weed shifts occur because of repeated practices.ix

SECTION I - HERBICIDE-RESISTANT WEEDSHerbicide resistance is defined as the innate ability of a species to survive and reproduce after treatmentwith a dose of herbicide that would normally be lethal. It is important to differentiate herbicide resistance from herbicide tolerance, defined as the ability of a plant to compensate for the damaging effectsof the herbicide with no physiological mechanisms involved. Resistant plants may be resistant to oneclass of herbicides within a group or to several herbicide classes within one group. For example, abiotype of wild oats (Avena fatua) that is resistant to fenoxaprop (an ACCase inhibitor) may be resistant toseveral other ACCase inhibitors. This is known as cross-resistance. Multiple resistance is defined as abiotype that is resistant to several groups of herbicides with different biochemical targets, such as triazines andALS inhibitors. To control weeds with multiple resistance, it is necessary to use herbicides that are not in eitherof these groups, or some other alternative control strategy.In recent years, herbicide-resistant weeds have developed from academic curiosities into serious managementproblems. Herbicide resistance in at least one weed species has occurred in almost every county in the tri-statearea. Resistance seems to evolve fastest in continuous monoculture cropping situations, and if weeds likekochia and Russian thistle are involved, it can rapidly spread to adjacent cropland and rangeland, since seedsand pollen are widely disseminated. Herbicide-resistant weeds will continue to pose significant challenges inoverall weed management schemes for the foreseeable future.WHERE DO RESISTANT WEEDS COME FROM?Herbicide-resistant weed biotypes are thought to develop from only one or a few plants already presentwithin a population, usually at a very low frequency (maybe one in several million). Weeds, like everyother organism, have inherent genetic variability that allows a few scattered individuals to surviveherbicide treatment. These resistant individuals are not usually noticed during the first few years aherbicide is used. By repeatedly using the same herbicide over time, the applicator removes all thesusceptible weeds and selects for the resistant plants. Then, depending on the selection intensity andlife history of the weed species (see below), the resistant weed population will continue to grow andexpand. Weed scientists and company representatives say that most growers won’t complain until about25% of the weeds in a given field become resistant.The four most important factors controlling the appearance of resistant weeds are:1) Selection Intensity. This term refers to how effective the herbicide is at killing weeds and howoften the weed population is exposed to the herbicide. If the herbicide is highly effective, appliedoften, has long soil residual activity, and is the only practice for controlling a particular weed, thenthe selection intensity for resistance is very high. Under these conditions, selection of resistantweeds can occur within a few years (e.g., ALS resistance in kochia, ACCase resistance in grasses). Incontrast, if a herbicide is only marginally effective on a certain species, is only applied sporadically, and/orhas no soil residual activity, then the selection of resistant weeds will be slower.2) Weed Biology. Some weed species have high levels of genetic variability, meaning that a single speciesconsists of many different varieties or biotypes. Generally, weeds like kochia that are cross-pollinated(pollen is spread from one plant to another by insects or wind) have more diversity than those that are selfpollinated like wild oats. Weeds with more genetic variability generally develop resistance to herbicidessooner, since the initial frequency of resistant individuals before spraying is probably higher.1

3) Herbicide Mode of Action. Many herbicides have similar modes of action and kill weeds by targeting thesame enzyme. For example, sulfonylurea (Ally and Harmony GT) and imidazolinone (Pursuit and Assert)herbicides target the same p

weed control strategies in the best possible way with the goal of maintaining weed densities at manageable levels while preventing shifts in weed populations to more difficult-to-control weeds. Combining as many of the following practices as possible will allow you to design an IWM program: † Avoid weed establishment; eliminate individual .

3.2 Chemical Weed Control 10 3.3 Thermal Weed Control 14 3.4 Biological Weed Control 15 4.0 Natural Areas Weed Management 16 4.1 Purpose 16 4.2 Limitations 16 4.3 Study Area 16 4.4 Weed Management Site Prioritisation 18 4.5 Weed Monitoring 20 4.6 Weed Prevention 22 4.7 Weed Control 24 4.8 Partnerships 28 5.0 Parks and Urban Landscaping

W-253 2018 NORTH DAKOTA WEED CONTROL GUIDE Compiled by: Rich Zollinger Extension Weed Science Contributors: Mike Christoffers Research Weed Science, Weed Genetics Caleb Dalley Research Weed Science, Hettinger R&E Center Greg Endres Extension Area Agronomist, Carrington R&E Center Greta Gramig Research Weed Science, Weed Ecology Kirk Howatt Research Weed Science, Small Grains/Minor Crops

Introduction to Weed Science and Weed Identification . Definition of a Weed A plant growing where it is not wanted (Oxford Dictionary) Any plant or vegetation, excluding fungi, interfering with the objectives or requirements of people (European Weed Science Society)

A guide to spring weed control Spring weed control in established pasture There are three key steps to effective spring weed control in established pasture - timing, weed identification and product selection. 1. Timing One of the most common mistakes made with spring weed control is spraying too late.

control, weed control, weed control '. Of course there are other important tasks, but weed control is surely one of the most vital! It is important to achieve good weed control in the 1m2 around each seedling. However the amount of ground disturbance should be kept to a minimum as open ground is an invitation to fresh weed establishment.

Introduction Weed management has been identified in many surveys of organic growers and farmers as being their number one problem, often by over 80% of respondents. Good weed management is essential for a successful organic enterprise. However, the amount of detailed information on organic weed . Organic Weed Management: A Practical Guide .

weed dry weight and recordedhigher weed control efficiency in groundnut.The use of herbicide as a means of weed management is fast gaining momentum especially in groundnut cultivation. Herbicides are efficient in suppressing or modifying weed growth in such a way as to prevent interference with crop establishment (Kunjo, 1981).

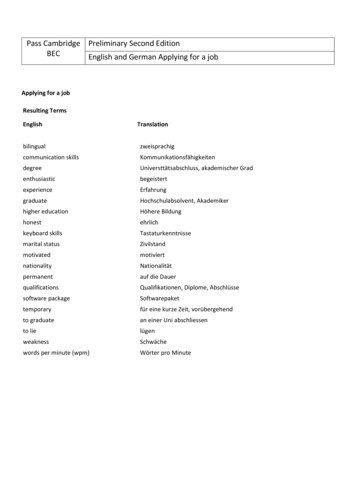

higher education Höhere Bildung honest ehrlich keyboard skills Tastaturkenntnisse marital status Zivilstand motivated motiviert nationality Nationalität permanent auf die Dauer qualifications Qualifikationen, Diplome, Abschlüsse software package Softwarepaket temporary für eine kurze Zeit, vorübergehend to graduate an einer Uni abschliessen to lie lügen weakness Schwäche words per .