Physiological Demands Of Eventing And Performance Related Fitness In .

Physiological Demands of Eventing andPerformance Related Fitness in Female HorseRidersJ. DouglasA thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of theUniversity’s requirements for the Degree of Doctorof Philosophy2017University of Worcester

!DECLARATIONI declare that this thesis is a presentation of my own original research work and all thewritten work and investigations are entirely my own. Wherever contributions of othersare involved, this is clearly acknowledged and referenced.I declare that no portion of the work referred to in this thesis has been submitted foranother degree or qualification of any comparable award at this or any other university orother institution of learning.Signed:Date:I

!ABSTRACTIntroduction: Scientific investigations to determine physiological demands andperformance characteristics in sports are integral and necessary to identify general fitness,to monitor training progress, and for the development, prescription and execution ofsuccessful training interventions. To date, there is minimal evidence based researchconsidering the physiological demands and physical characteristics required for theequestrian sport of Eventing. Therefore, the overarching aim of this thesis was toinvestigate the physiological demands of Eventing and performance related fitness infemale riders.Method: The primary aim was achieved upon completion of three empirical studies.Chapter Three: Anthropometric and physical fitness characteristics and training andcompetition practices of Novice, Intermediate and Advanced level female Event riderswere assessed in a laboratory based physical fitness test battery. Chapter Four: Thephysiological demands and physical characteristics of Novice level female event ridersthroughout the three phases of Novice level one-day Eventing (ODE) were assessed in acompetitive Eventing environment. Chapter Five: The physiological demands and muscleactivity of riders on live horses in a variety of equine gaits and rider positions utilisedduring a novice ODE, including jumping efforts, was assessed in a novel designed livehorse exercise test.Results: Chapter Three reported that aside from isometric endurance, ridersanthropometric and physical fitness characteristics are not influenced by competitivelevel of Event riding. Asymmetrical development in isometric leg strength was reportedwith increased levels of performance; riders reported below average balance andhamstring flexibility responses indicating limited pelvic and ankle stability, and tightnessin the hamstring and lower back. Chapter Four reports that physiological strain basedupon heart rate during Eventing competition is considerable and close to maximal,however blood lactate data was not supportive of this supposition. Chapter Five reportsthat during horse riding, riders are exposed to intermittent and prolonged isometricmuscle work. During horse-riding, riders have an elevated heart rate compared to theoxygen requirements for the activity, in addition to moderate blood lactate concentrations.II

!Conclusion: This thesis indicates that the most physiologically demanding aspect ofEvent riding is the light seat canter and where jumping efforts are introduced. Duringthese positions and gait combinations, heart rate is elevated compared to oxygen uptake.Additionally, moderate blood lactate (BLa) concentrations are reported suggesting thoughcardiac strain is high, physical demands are moderate. The use of heart rate as a markerof exercise intensity during horse riding activities is not appropriate as it is not reflectiveof actual physiologic demand and BLa may be a more indicative marker of exerciseintensity for equestrian investigations.There are many factors that may affect heart rate as discussed throughout the thesis, suchas cognitive anxiety, heat stress and isometric muscle work. The data from this thesisspeculates that the elevated heart rate is in part affected by isometric muscle work; similarphysiological profiles exist in sports such as Sailing and are attributed to the quasiisometric theory. Though this thesis is not able to comprehensively conclude thatphysiological responses are a direct result of quasi isometrics, the data set does infer thismay be a potential contributor and as such is a recommended topic for future research.Regardless of the causal mechanism, riders should be conditioned to tolerate high heartrates to enable optimal physical preparation for competition; the physical characteristicsand physiological demands placed upon Event riders reported throughout this thesisprovides information for coaches and trainers to consider when designing suchinterventions.III

!ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThere has been a huge support network available to me throughout the PhD process; froman academic standpoint I wish to thank my Director of Studies, Prof. Derek. M. Petersand Dr. Mike Price for their feedback and support. I would like to thank the staff at theInstitute of Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Worcester for their support andpatience, I would like to particularly thank Colin Hill, for ongoing support and technicalassistance. I would additionally like to thank Hartpury College for support and use offacilities. Thank you to Polar EU for the support of this research by supplying the projectwith heart rate monitors.Importantly, I would like to specifically thank all those who acted as participants in theenclosed chapters (human and equine), you have all taught me a great deal – thank youfor your time and energy!This PhD has come with me through a nearly a decade of my life, saw me get married,birth two beautiful children, and move through three countries. As such, there are so manypeople that have impacted and supported me on this journey that I cannot name everyone,but if you are reading this and know me personally, please know I value your support.To Lee, Connor and Euan, I appreciate your patience and support throughout this entirejourney. To my family, thank you for your support and inspiration, for the stubborn gene,for endless enthusiasm, for installing a good work ethic, and of course, a passion forequestrian sports. To my friends, thanks for every hug, every necessary glass of wine andinstalling the PP mentality, there are far too many of you to name, but you will know whoyou are! To all my office friends I will always look back on early PhD days fondly, it isgood to know there are other people as crazy as I to embark such academic journeys!IV

!TABLE OF CONTENTSDECLARATION . IABSTRACT. IITABLE OF CONTENTS. VLIST OF TABLES .VIILIST OF FIGURES . IXGLOSSARY, UNITS & ABBREVIATIONS . XTHESIS RESEARCH DISSEMINATION .XIICHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION . 11.1 Purpose of the Research . 31.2 Research Aims and Objectives . 41.3 Delimitations . 4THESIS OVERVIEW. 5CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW . 72.1 The Equestrian Sport Context . 72.2 Intricacies of the Equestrian Sport of Eventing . 122.3 Equestrian Specific Research Literature . 142.4 Performance Related Fitness. 412.5 Sports Specific Physiological Testing . 452.6 Factors Affecting Physiological Mechanisms . 492.7 Summary . CTERISTICS AND THE TRAINING AND COMPETITION PRACTICES OFNOVICE, INTERMEDIATE AND ADVANCED EVENT RIDERS . 613.1 Introduction . 613.2 Methods. 643.3 Results . 803.4 Discussion . 873.5 Conclusion . 96CHAPTER FOUR: THE PHYSIOLOGICAL DEMANDS OF NOVICE ONE-DAYEVENTING AND THE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF NOVICE FEMALEEVENT RIDERS . 984.1 Introduction . 984.2 Method . 1014.3 Results . 1074.4 Discussion . 1154.5 Conclusion . 127!V

!CHAPTER FIVE: THE PHYSIOLOGICAL AND NEUROMUSCULAR DEMANDSOF A LIVE HORSE EXERCISE TEST. 1295.1 Introduction . 1295.2 Methods. 1335.3 Results . 1425.4 Discussion . 1515.5 Conclusion . 161CHAPTER SIX: DISCUSSION . 1626.1 Physiological Demands of Horse-Riding. 1626.2 Muscle Activity During Horse-Riding. 1666.3 Interpretation of the Physiological and Muscular Responses to Horse-Riding . 1676.4 The Physiological Demands of Eventing . 1706.5 Limitations . 176CHAPTER SEVEN: CONCLUSIONS . 1787.1 Future Research Directions . 178CHAPTER EIGHT: REFERENCE LIST . 181CHAPTER NINE: APPENDICIES . 204APPENDIX ONE. 205COMPARISON OF MECHANICAL HORSE, CYCLE ERGOMETER ANDTREADMILL EXERCISE MODES ON HEART RATE, OXYGEN UPTAKE ANDBLOOD LACTATE RESPONSE IN FEMALE HORSE-RIDERS. 205A.1 Introduction . 205A.2 Methods. 207A.3 Results . 211A.4 Discussion . 214A.5 Conclusion . 220APPENDIX TWO. 222APPENDIX THREE . 227Appendix 3a . 227Appendix 3b:. 233Appendix 3c: . 244Appendix 3d:. 251Appendix 3e: . 254!VI

!LIST OF TABLESTable 2.1: The components of off-horse physical literacy riders should aim to achieve ateach stage of the LTPD model. . 11Table 2.2: Taxonomy of rider status categories in equestrian sports (Williams and Tabor,2017). . 15Table 2.3: Body composition data reported for equestrian athletes. 17Table 2.4: Comparison of oxygen consumption (ml.min.kg-1)* and pulmonary ventilation(l.min-1) between Westerling (1983) and Devienne and Guzennec (2000). . 33Table 3.1: Anthropometric and performance test characteristics of Novice, Intermediateand Advanced Event riders (Mean SD). . 81Table 3.2: Isokinetic concentric and eccentric strength in dominant (D) and non-dominant(ND) leg (quadriceps and hamstring) flexors and extensors at 60 .sec-1 and 180 .sec-1 innovice, intermediate and advanced event riders . 82Table 3.3: Descriptive statistics for physiological variables collected throughout the cycleergometer test . 82Table 3.4: Summary of item responses between Novice, Intermediate and Advancedathletes (Novice n 11, Intermediate n 8, Advanced n 7). . 84Table 3.5: Summary of questionnaire item responses between riders that completedadditional un-mounted training to those that did not. . 86Table 4.1: Descriptive information for number of participants collected at eachcompetition venue. . 102Table 4.2: Mean heart rates in the sixty seconds preceding each competition phase ofNovice ODE (mean SD) (DR n 25; SJ n 25; XC n 20). 107Table 4.3: Heart rates (beats.min-1) throughout the three phases of Novice ODE (mean SD) (DR n 21; SJ n 21; XC n 21). 108Table 4.4: Blood lactate concentration pre and post competition throughout the threephases of Novice ODE (mean SD) (DR n 25; SJ n 25; XC n 20). 110Table 4.5: Mean ( SD) grip strength (kg) and relative changes (%decrease) in dominantand non-dominant hand at baseline, and post the three phases of Novice ODE riding (DRn 27; SJ n 27; XC n 22). . 111Table 4.6: Mean ( SD) duration (minutes:seconds) of the three phases of Novice ODEriding for warm up and competition (DR n 25; SJ n 25; XC n 20). . 112Table 4.7: Mean duration of recovery (hour:minutes:seconds) between the DR and SJphase and between the SJ and XC phase. . 112Table 4.8: Descriptive statistics for physiological variables collected throughout and atthe termination of the cycle ergometer test (n 17). . 114!VII

!Table 4.9: Descriptive statistics for measured and estimated based on laboratoryequivalent physiological in-field data (n 17). . 114Table 5.1: Gait and position combination descriptions and durations for each stage of thelive horse exercise test protocol. . 137Table 5.2: A description of the EMG analysis methods used. . 142Table 5.3: Physiological reference data obtained in the laboratory and test data obtainedduring the live horse exercise test. . 143Table 5.4: Descriptive data for physiological variables throughout the live horse test.144Table 5.5: Live horse test bi-variate data and associated r values . 146Table 5.6: Descriptive data for composite muscular activity. . 147Table 6.1: Brief overview of the physiological and biomechanical demands related toeach individual phase of a Novice One-Day Eventing and associated suggested trainingmethods or areas for future intervention design. . 175Table A.1: Gait and position combination descriptions for each stage of the mechanicalhorse test protocol. . 210Table A.2: Mean SD (range) Peak oxygen consumption (V̇ O2peak), peak heart rate(HRpeak) peak RPE (RPEpeak) and peak BLa (BLapeak) attained for all three exercise modes. 211Table A.3: Mean oxygen consumption (V̇ O2), mean heart rate (HR), mean RPEo (RPEo)and mean BLa (BLa) attained reported by stage of exercise testing for the MH(mean SD). . 214!VIII

!LIST OF FIGURESFigure 3.1: BatakTM Board (Batak 2015) . 70!Figure 4.1: Relative duration spent in each of the five heart rate zones (%HRmax) for thethree warm up phases of Novice ODE (DR n 25; SJ n 25; XC n 20). . 108!Figure 4.2: Relative duration spent in each of the five heart rate zones (%HRmax) for thethree phases of Novice ODE (DR n 25; SJ n 25; XC n 20). . 109!Figure 4.3: Mean ( SD) blood lactate concentration (mmol l-1) for the three phases ofNovice ODE riding (DR n 27; SJ n 27; XC n 22). . 110!Figure 5.1: Upright, Crosspole and Oxer. NB: These are not images of the actual jumpsused throughout testing (Courtesy of the Author 2015) . 136!Figure 5.2: Figure to Demonstrate Equestrian Arena Set-up. . 138!Figure 5.3: Muscular anatomy to identify muscles analysed during the riding test (Imagepurchased from www.Bigstockphoto.com) . 140!Figure 5.4: Mean V̇ O2, HR and VE for each stage on the live horse test; Walk (W), sittingtrot (ST), rising trot (RT), canter (C), light seat canter (LC), fast canter (FC) and jump (J). 146!Figure 5.5: Scatter plot of V̇ O2 and HR during the live horse exercise test. . 147!Figure 5.6: Comparison of EMG for the four individual muscles during each stage of thelive horse protocol A) rectus femoris B) rectus abdominis C) lattisimus dorsi D) flexorcarpi radialis. *p 0.05. . 149!Figure 5.7: Representative bilateral EMG trace (n 1) during the jump stage. Red verticallines indicate point of take off. . 150!Figure A.1: Racewood Mechanical Horse Simulator . 210!Figure A.2: Scatter plot of heart rate (HR) and oxygen consumption (V̇ O2) for all threeexercise modes, a) Mechanical Horse, b) Cycle Ergometer, c) Treadmill. . 213!!IX

!GLOSSARY, UNITS & ABBREVIATIONS1RM 1 repetition maximumBE British EventingBE100 British Eventing 100BE90 British Eventing 90BETA British Equestrian Trade AssociationBHIC British Horse Industry ConfederationBLa Blood Lactate ConcentrationBMI Body Mass Indexbeats.min-1 Beats Per Minutecm centimetreDR DressageEMG ElectromyographyEquestrian a reference to horse ridingEquestrian Athlete Pertains to the rider (also termed horse-rider)Equitation the practise of horse ridingf critical f statisticFAPT Front Abdominal Power TestFEI Fédération Equestre InternationaleGS Grip StrengthH Live Horse Exercise TestHR Heart Ratekg Kilgograml LitreLT Lactate ThresholdLTPD Long Term Participant Developmentm meters!X

!MAV Mean Absolute ValueMH Mechanical Horse Simulatormmol MillimoleMUAPs Motor Unit Action PotentialsmV MillivoltsMVC Maximal Voluntary ContractionN NewtonNm Newton MetreODE One Day Eventp probability valuer correlation coefficientr2 co-efficient of determinationRPE Rating of Perceived ExertionRPEo Overall Rating of Perceived ExertionRPEp Peripheral Rating of Perceived ExertionRT Rising Trots SecondsEMG Surface ElectromyographySJ Show Jumpingt critical t-statisticV VoltVE VentilationV̇ O2 Oxygen UptakeV̇ O2max Maximal Oxygen UptakeV̇ O2peak Peak Oxygen UptakeW Wattsµm MicrometreµV MicrovoltsXC Cross Country!XI

!THESIS RESEARCH DISSEMINATIONDouglas, J., Price, M., Peters, D.M. (2012) A systematic review of physiological fitnessand biomechanical performance in equestrian athletes. Comparative Exercise Physiology,8 (3), 53-62.Douglas, J., Price, M., Peters, D.M. (2012) Anthropometric and fitness characteristics offemale Novice, Intermediate and Advanced Level Event riders. World Congress ofPerformance Analysis in Sport IX, 25th-18th July 2012, Worcester, UK.Johnson, J., Price, M., Peters, D.M. (2011) The physiological demands of the three phasesof competitive One-Day Eventing in Novice female Event riders. The 16th AnnualCongress of the European Congress of Sports Sciences, 6-9th July 2011, Liverpool, UK.Johnson, J., Price, M., Peters, D.M. (2011) Maximal aerobic power and lactate thresholdin Novice female Event riders is affected by additional un-mounted training. The 16thAnnual Congress of the European Congress of Sports Sciences, 6-9th July 2011,Liverpool, UK.!XII

!CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTIONEventing is an equestrian discipline comprising of three phases: Dressage (DR), ShowJumping (SJ) and Cross Country (XC), the difficulty of each phase is progressive withcompetitive level. The demands are increased by including more complex gymnasticmovements in the DR phase, increasing height and complexity of jump combinations inthe SJ phase and increases in length, height and complexity of jumps for the XC phase,there is also manipulation of phase ordering and number of competition days (e.g. One,Two or Three Day Eventing) at the advanced levels. Dressage is an event in which therider and horse perform a series of exact movements in a semi enclosed arena over aperiod of between approximately 5-8 minutes with a percentage of scores attributable torider posture/position. This phase assesses the harmony between horse and rider andanecdotally requires postural control and core stability to produce what is termed an‘independent seat’ that permits the rider to direct and aid the horse without overt bodymovement (von Dietze 1999). Show Jumping, requires the rider and horse to navigate acourse of between 8-20 jumps at a pre-determined height, lasting for approximately 5minutes and has been suggested to require agility, speed, strength, technique andprecision of the rider and horse (Houghton Brown 1997). The XC phase requires the riderand horse to navigate an undulating course of between 1,500-4000m comprising of 1240 natural solid obstacles at a gallop (British Eventing 2009).Equestrian Team GB have proven successful at the elite level over the 2000-2016Olympic Games with all five podium representations between 2000-2008 occurring as aresult of the success of the British Eventing teams. The London 2012 Olympics was themost successful games to date with Equestrian Team GB being awarded five Olympicmedals including two gold, Rio 2016 saw Equestrian Team GB being awarded 3 medals,two gold and a silver. British Eventing (the national governing body for Eventing in theUK) holds over 180 events annually during the competitive season (March – October)and manages over 94,000 competition entries for over 15,000 members (British Eventing2017) and is a popular sport for both spectators and competitors. As a successful sport,GB Equestrian receive priority funding to ensure continued success at the elite level, as!1

!such there is support available for both horses and their riders to ensure each athlete is inoptimal physical condition for competition.The research problem here exists, there is a dearth of research investigating thephysiological demands of event riding (Roberts et al. 2010) on which trainers and coachescan base physical preparation strategies. It is well documented that a thoroughunderstanding of the specific physiological requirements and performance related fitnessvariables in a particular sport is necessary for an athlete’s strength and additionallyconditioning of energy demands to be specifically prepared, thus ensuring an effectivetransfer of physical improvements from the gym to the specific sport setting (Cunniffe etal. 2009; Gonzales-Millian et al. 2016; Highnam et al. 2016).Literature to date indicates that as the horse and rider progress through the equine gaits(walk, trot, canter), the riders heart rate and oxygen consumption increase and within theDR phase, aerobic metabolism dominates. It is generally the faster gaits, and jumpingsuch as in SJ and XC that require the rider to adopt a ‘forward’ position where the ridersare then un-seated in an isometric semi-squat position, causing weight bearing to bethrough the rider’s legs (Roberts et al. 2010). It is apparent that positional differencesrequired for fast cantering and jumping increase anaerobic metabolic system requirementswith reported increases in cardiovascular load and associated increased blood lactatevalues (Guitérrez Rincón 1992; Trowbridge et al. 1995; Roberts et al. 2010; Perciavalleet al. 2014) and therefore greater physiological strain in these phases of Eventing can beassumed. More recent work in horse-riders is suggestive that heart rate is elevated whencompared to other cardio-metabolic parameters (Sainas et al. 2016), and that the use ofheart rate as a measure of physical effort is not accurate during riding activities and is animportant consideration when interpreting available data.Elevations in heart rate can be influenced by many variables including cognitive anxiety;the nature of riding an unpredictable animal is a risk and thus some elevations in heartrate in response to competitive and situational anxiety seem reasonable. The causalmechanism for elevation in a rider’s heart rate and not other physiological variablesduring equestrian activities has yet to be investigated but is an important considerationfor the interpretation of physiological demand and the use of heart rate monitoring duringan equestrians training programme.!2

!Sports where isometric muscle actions predominate, such as Sailing, Windsurfing andMotorcorss have reported a high heart rates compared with other physiological markersof exercise intensity, such as oxygen consumption and blood lactate (Cunningham andHale 2007; Konittinen et al. 2002; Konittinen et al. 2008; Sheel et al. 2004; Vogiatziz etal. 2002). Researchers have identified that physiological data were not matched i.e. heartrate was higher than necessary for recorded oxygen uptake with moderate blood lactateconce

physiological demands and physical characteristics of Novice level female event riders throughout the three phases of Novice level one-day Eventing (ODE) were assessed in a competitive Eventing environment. Chapter Five: The physiological demands and muscle activity of riders on live horses in a variety of equine gaits and rider positions utilised

The NSW Branch of Equestrian Australia (ENSW) has developed these Rules for Low Level Events effective from January 2005 and updated April 2013 with the assistance of Eventing New South Wales (EvNSW). They cover all unofficial eventing competitions and training days held in NSW, known as “Low level Events”

table of contents introduction to alberta postpartum and newborn clinical pathways 6 acknowledgements 7 postpartum clinical pathway 8 introduction 9 physiological health: vital signs 12 physiological health: pain 15 physiological health: lochia 18 physiological health: perineum 19 physiological health: abdominal incision 20 physiological health: rh factor 21 physiological health: breasts 22

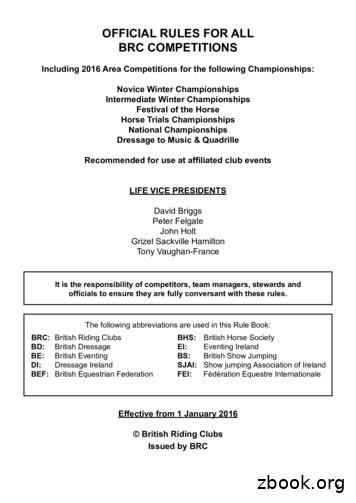

The following abbreviations are used in this Rule Book: BRC: British Riding Clubs BHS: British Horse Society BD: British Dressage EI: Eventing Ireland BE: British Eventing BS: British Show Jumping DI: Dressage Ireland SJAI: Show jumping Association of Ireland BEF: British Equestrian Federation FEI: Fédération Equestre Internationale

The physiological impacts of operational demands can impair worker cognitive functioning. Awareness-based models of physiological and cognitive performance impacts can be taught and can influence subsequent activity. The ability to record and transmit physiological variables from first responders has been available for

2.1 Physiological and Anthropometric Characteristics of Mixed Martial Arts Competitors 5 5 2.2 Quantifying the Physical and Physiological Demands of Performance 7 o 2.2.1 Introduction to Maximal Oxygen Consumption Testing 7 o 2.2.2 Maximal Oxygen Consumption in MMA 8 o 2.2.3 Limitations of Maximal Oxygen Consumption for MMA 9

Physical demands and physiological aspects in elite team handball in Germany and Switzerland: an analysis of the game. MOJ Sports Med. 2020;4(2):55‒62. DOI: 10.15406/mojsm.2020.04.00095 Physical demands and properties The player's position requires certain physical properties. The right wing and right back are normally and preferable left .

movement patterns, physical and physiological demands.[2] Furthermore, there are three major formats of the game, i.e. -day games, one day games (ODG) and T20 games. The latter two are shorter formats of the game which include more intense movements and consequently impose dissimilar physical and physiological demands on players.[3,4] Training

Taking responsibility for our own physical, emotional, mental and spiritual well-being can be a radical political act in these times where legislation and standardised medical practice often support or even create ill-health. Also, rapid cultural change has been facilitated through access to personal computer technology. It is now easy to find ‘alternative versions’ of events, both .