Proof

Multiethnicityand Migrationat TeopancazcoInvestigations of aTeotihuacan Neighborhood CenterproofEdited by Linda R. ManzanillaUniversity Press of FloridaGainesville · Tallahassee · Tampa · Boca RatonPensacola · Orlando · Miami · Jacksonville · Ft. Myers · Sarasota

Copyright 2017 by Linda ManzanillaAll rights reservedPrinted in the United States of America on acid-free paperThis book may be available in an electronic edition.22 21 20 19 18 176 5 4 3 2 1ISBN 978-0-8130-5428-5Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataproofThe University Press of Florida is the scholarly publishing agency for the State University Systemof Florida, comprising Florida A&M University, Florida Atlantic University, Florida Gulf CoastUniversity, Florida International University, Florida State University, New College of Florida,University of Central Florida, University of Florida, University of North Florida, University ofSouth Florida, and University of West Florida.University Press of Florida15 Northwest 15th StreetGainesville, FL 32611-2079 BOG logo

1TeopancazcoA Multiethnic Neighborhood Centerin the Metropolis of TeotihuacanLinda R. ManzanillaFew preindustrial urban settlements may be cited as key sites for their regions; in ancient times Chang’an, Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, andTeotihuacan are perhaps the greatest urban developments. Yet few of theseurban developments are as complex, corporate, exceptional, and multiethnic as Teotihuacan in central Mexico. René Millon (1973, 1981, 1988, 1993)brilliantly unveiled the urban grid and orthogonal plan of Teotihuacan,identifying its likely foreign wards and craft production areas. During theClassic period, the first six centuries AD, this huge metropolis housed acorporate society involved in impressive construction activities, massiveproduction of craft goods, and extensive movement of sumptuary piecesalong trade routes (Manzanilla 2001b, 2006a, 2006b, 2009a, 2011b, 2015).A number of features make Teotihuacan exceptional in Mesoamerica(Manzanilla 1997, 2007b):proof1. Its large physical layout, urban planning, and grid (20 km2) (Millon1973) (Figure 1.1).2. Its multiethnic society, evident by foreign neighborhoods on theperiphery (the Oaxaca Barrio, the Merchants’ Barrio, the Michoacán Compound, and probably others) (Figure 1.2), as well as foreign labor fostered by the intermediate elites of the neighborhoodcenters (Manzanilla, ed. 2012; Manzanilla 2015).3. Its polarized settlement pattern with a huge metropolis along withnumerous scattered villages and hamlets in the Basin of Mexicowhere the food producers lived.4. Its corporate organization, evidenced in multifamily apartmentcompounds housing independent families that shared a particular

2 · Linda R. Manzanillatask, and perhaps also evident in an apparent system of corulershipby four lords, representing the four administrative sectors of thecity (Manzanilla 2009a) (Figure 1.3).5. As the capital of a peculiar type of state that I have called “the octopus type,” where the head is represented by a great planned cityand the tentacles are the corridors of allied sites extending towardregions where sumptuary goods and raw materials are found, mostof them consumed by elites (Manzanilla 2006d, 2007c, 2009a).The eruptions of the Popocatépetl volcano in the first century AD (Plunketand Uruñuela 1998, 2000) stimulated the arrival of large groups of peoplefrom Puebla and Tlaxcala to a Teotihuacan Valley already dotted with Formative period villages, such as Cuanalan (Manzanilla 1985, 2001b). As Millon has pointed out, the Teotihuacan Valley offered several advantages: anabundance of freshwater springs; volcanic raw materials for construction(e.g., volcanic scoria, andesite, basalt, volcanic tuff); obsidian deposits inOtumba and Pachuca (obsidian being the main raw material from whichthe lithic technology in central Mexico was produced); a location on themost direct route from the Gulf Coast to the Basin of Mexico, skirting thehigh Sierra Nevada (Manzanilla 2001b; Millon 1973).Beginning in the Tlamimilolpa phase (AD 200–350) the great orthogonal city was aligned 15 17' east of north; before this time we find largebuilding complexes in different parts of the valley that might represent migrant groups or factions who participated in the construction of the threemain pyramids at the site over long periods. During the Tlamimilolpaphase construction modules appear for the first time: there were multifamily apartment compounds and foreign neighborhoods; the streets andbuildings were arranged at right angles; the San Juan River was channeledto follow the urban grid plan; there was an east-west avenue that crossedthe Street of the Dead at right angles and may have divided the city intofour quarters (Millon 1973).Just as fifteenth-century Tenochtitlan was divided into four campan, ordistricts, the city of Teotihuacan may have had four sectors (see Figure1.3) corresponding to the administrative seats for the state and corulershipsystem (see Manzanilla 2009a). My team and I have wondered if the areanamed La Ventilla 92–94, in the southwestern sector of the city, is a neighborhood center or the administrative center of the southwestern district ofthe city. It seems unusual for its planning, its functional formalization, andthe location of a huge administrative space in the Glyph Courtyard (GómezChávez 2000; Gómez Chávez et al. 2004).proof

proofFigure 1.1. Locationof Teopancazco inthe Teotihuacanmetropolis (basemap by René Millon 1973; redrawnby Rubén Gómez).

proofFigure 1.2. Hypothesizedconcentric rings of Teotihuacan: the outer ringcontains foreign wards,the inner ring containsmultiethnic neighborhoods headed by intermediate elites of Teotihuacan(drawing by Linda R.Manzanilla and RubénGómez; see Manzanilla2009a:Figure 2.15).

proofFigure 1.3. Four proposeddistricts in Teotihuacan,from which the fourco-rulers may have come(drawing by Linda R.Manzanilla, Rubén Gómez, and César Fernández; see Manzanilla2009a:Figure 2.17).

6 · Linda R. ManzanillaAround AD 350 there may have been a crisis in the city, as evidenced byvarious termination rituals (the destruction of numerous pots and objectsat ritual sites; the decapitation of a large number of adults and depositionof their heads in vessels at Teopancazco; the destruction of the Pyramid ofthe Feathered Serpent in the Ciudadela); and the building of the Xolalpancity on top of the former construction phase (Manzanilla 2002b, 2006b).There are at least two potential causes of this crisis: (1) a possible eruptionof the Xitle volcano in the southern sector of the Basin of Mexico (Siebe2000:Table I) and the resulting demographic displacements it entailed;and/or (2) a political crisis that climaxed with the destruction and burningof the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the construction of another platform that concealed its facade, and the possible expulsion of its adepts. Ihypothesize that a rivalry between two groups in the corporate corulershipsystem—jaguars and serpents—may have provoked a struggle that weakened the serpent group (Manzanilla 2002c, 2008a). I believe this conflictmight be depicted in the Mural of the Mythological Animals, which showsdifferent animals (felines, canids, birds) attacking serpents. In addition, thepresence of two prehispanic tunnels under the main axis of the two pyramids whose facades face west (the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid ofthe Feathered Serpent) may indicate that these two factions were competing to claim control of the axis mundi, or center of the cosmos, at theirpower base (Manzanilla 2009c, 2010).The new construction phase (Xolalpan, AD 350–550; BeramendiOrosco, González, and Soler Arechalde 2012; Beramendi Orosco, GonzálezHernández, et al. 2009; Manzanilla 2009b) was built on top of its predecessor; the monochrome red painting of this phase contrasts with the polychrome mural paintings of the Tlamimilolpa phase.The great city seems to have been the capital of a powerful and organizedstate; each building in the city fell within a planned urban grid, and onemight assume that the society was highly controlled. This may have beenthe case early on, with attempts to articulate ethnic and social diversitiesthrough state ritual, neighborhood ceremonies, and domestic ritual. Anexamination of Teotihuacan’s internal structure reveals a variety of neighborhoods (many of which may have represented the original enclaves ofgroups of different proveniences that arrived in the valley, where the intermediate elites orchestrated relations, production, and movements in thepursuit of particular interests.My hypothesis is that at the end of Teotihuacan’s history, the contradiction between the corporate structure of the state and the exclusionaryproof

Teopancazco: A Multiethnic Neighborhood Center in the Metropolis of Teotihuacan · 7structure of the strong “houses” that ruled the different neighborhoodsreached a breaking point, and the social and political fabric that had onceseemed highly resistant revealed its fragility and was torn. In fact, Teotihuacan may have been founded as the result of a multiethnic pact, a weakcoalition formed for massive craft production and movement of sumptuarygoods. The homelands of the ethnic groups that actively participated in thiswork eventually pulled out of Teotihuacan’s centripetal force (Manzanilla2011a).The intermediate elites who managed the neighborhood centers wereintensively involved in organizing trade and craft production activities,which required a large labor force. Each neighborhood procured sumptuary goods and workers from a particular region in Mesoamerica. Thecity was the central destination for cotton cloth, exotic animals, hides, pigments, minerals, rocks, semiprecious stones, and minerals, not to mentionthe people who carried the goods, expert craftspeople who served differentfunctions, and perhaps others who were sacrificed.I believe that in the Tlamimilolpa and Xolalpan phases, Teotihuacan wasmore or less a cluster of neighborhoods, each with a central hub and various functional sectors: a ritual space, an administrative sector, a militaryarea for the guard, a specialized craft production area, probably a medicaland childbirth sector, and a series of kitchens and storerooms to feed theworkers. These neighborhood centers may have been headed by the intermediate elite of Teotihuacan, who had relative autonomy of movement andwere involved in bringing expert craftspeople (including garment makers,painters, and lapidary experts) from other regions to make attire and headdresses, as well as importing sumptuary objects and raw materials (Manzanilla 2006b, 2007a, 2009a, 2015). These nobles sponsored caravans thattraveled along a route of allied sites toward enclaves on the Gulf Coast, inthe Bajío region and western Mexico, in southeastern Mexico, and otherareas (Manzanilla, 1992, 2001b, 2011b), bringing feline hides, feathers, cotton cloth, pigments, cosmetics, slate, mica, onyx, travertine, greenstone,jadeite, and other goods to the great metropolis (Manzanilla 2001b).Teopancazco was one such neighborhood, divided into functional sectors devoted to administration, ritual, garment making, medical care, foodpreparation for workers, and housing of military personnel (Figure 1.4; seealso Manzanilla 2006a, 2006b, 2009a, 2012c; Manzanilla et al. 2011), as discussed below.This chapter opens with an overview of current knowledge about Teopancazco, an interesting multiethnic neighborhood center situated southproof

acán Compound, and probably others) (Figure 1.2), as well as for-eign labor fostered by the intermediate elites of the neighborhood centers (Manzanilla, ed. 2012; Manzanilla 2015). 3. Its polarized settlement pattern with a huge metropolis along with numerous scattered villages and hamlets

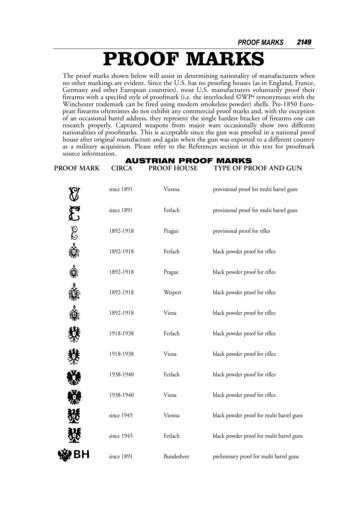

since 1950 E. German, Suhl choke-bore barrel mark PROOF MARKS: GERMAN PROOF MARKS, cont. PROOF MARKS: ITALIAN PROOF MARKS, cont. ITALIAN PROOF MARKS PrOOF mark CirCa PrOOF hOuse tYPe OF PrOOF and gun since 1951 Brescia provisional proof for all guns since 1951 Gardone provisional proof for all guns

PROOF MARKS: BELGIAN PROOF MARKSPROOF MARKS: BELGIAN PROOF MARKS, cont. BELGIAN PROOF MARKS PrOOF mark CirCa PrOOF hOuse tYPe OF PrOOF and gun since 1852 Liege provisional black powder proof for breech loading guns and rifled barrels - Liege- double proof marking for unfurnished barrels - Liege- triple proof provisional marking for

2154 PROOF MARKS: GERMAN PROOF MARKS, cont. PROOF MARK CIRCA PROOF HOUSE TYPE OF PROOF AND GUN since 1950 E. German, Suhl repair proof since 1950 E. German, Suhl 1st black powder proof for smooth bored barrels since 1950 E. German, Suhl inspection mark since 1950 E. German, Suhl choke-bore barrel mark PROOF MARKS: GERMAN PROOF MARKS, cont.

PROOF MARKS: GERMAN PROOF MARKSPROOF MARKS: GERMAN PROOF MARKS, cont. GERMAN PROOF MARKS Research continues for the inclusion of Pre-1950 German Proofmarks. PrOOF mark CirCa PrOOF hOuse tYPe OF PrOOF and gun since 1952 Ulm since 1968 Hannover since 1968 Kiel (W. German) since 1968 Munich since 1968 Cologne (W. German) since 1968 Berlin (W. German)

We present a textual analysis of three of the most common introduction to proof (ITP) texts in an effort to explore proof norms as undergraduates are indoctrinated in mathematical practices. We focus on three areas that are emphasized in proof literature: warranting, proof frameworks, and informal instantiations.

and Proof Chapter 2 Notes Geometry. 2 Unit 3 – Chapter 2 – Reasoning and Proof Monday September 30 2-3 Conditional Statements Tuesday October 1 2-5 Postulates and Proof DHQ 2-3 Block Wed/Thurs. Oct 2/3 2-6 Algebraic Proof DHQ 2-5 UNO Proof Activity

3.4. Sequential compactness and uniform control of the Radon-Nikodym derivative 31 4. Proof of Theorem 2.15 applications 31 4.1. Preliminaries 31 4.2. Proof of Theorem 1.5 34 4.3. Proof of Theorem 1.11 42 4.4. Proof of Theorem 1.13 44 5. Proof of Theorem 2.15 46 6. Proof of Theorem 3.9 48 6.1. Three key technical propositions 48 6.2.

integrate algebra and proof into the high school curriculum. Algebraic proof was envisioned as the vehicle that would provide high school students the opportunity to learn about proof in a context other than geometry. Results indicate that most students were able to produce an algebraic proof involving variables and a