State Action And “Under Color” Of State Law

Chapter 2State Action and “ Under Color”of State LawU.S. Const. amend. XIV (1868)§ 1: All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein theyreside. No State s hall make or enforce any law which s hall abridge the privileges orimmunities of citizens of the United States; nor s hall any State deprive any personof life, liberty, or property, without due pro cess of law; nor deny to any personwithin its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.§ 5: The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.18 U.S.C. § 242Whoever, u nder color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protectedby the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to dif fer ent punishments, pains,or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, orrace, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, s hall be fined u nder thistitle or imprisoned not more than one year, or both; and if bodily injury results fromthe acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include the use,attempted use, or threatened use of a dangerous weapon, explosives, or fire, shallbe fined u nder this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if deathresults from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts includekidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt tocommit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, s hall be fined u nder thistitle, or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both, or may be sentenced todeath.42 U.S.C. § 1983 very person who, uE nder color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, orusage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes tobe subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured bythe Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law,suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress . . .15

162 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Law§ 2.01 Preliminary Word on Action UnderColor of State LawIn Brentwood Acad emy v. Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association (2001) andLugar v. Edmondson Oil (1982), the Court explained that the F ourteenth Amendmentrequirement of action by a state and the § 1983 requirement of a person acting “ undercolor” of state law together limit the reach of federal law and federal courts, protect thepower of state institutions, and maintain an appropriate federal- state balance. State action“preserves an area of individual freedom by limiting the reach of federal law,” allowingprivate persons (non- state actors or persons not acting under color) to act f ree of constitutional limitations or the threat of constitutional liability. It prevents the imposition ofliability on state or local governments for conduct beyond their control, limiting governmental liability to constitutional violations for which “ ’it can be said that the Stateis responsible for the specific conduct of which the plaintiff complains’ ” because the conduct is “fairly attributable” to the state. The statutory “ under color” ele ment confines§ 1983 to the constitutional limits of the F ourteenth Amendment, as § 1983 was enactedpursuant to Congress’ § 5 enforcement power. Any § 1983 claim must be based on an actual deprivation of a right secured by the Fourteenth Amendment, which only occursif the unconstitutional conduct was performed by governmental, not private, actors.(Heffernan v. City of Paterson (2016)).Lugar announced a two- step inquiry to decide whether a defendant is a person subject to a § 1983 suit:First, the deprivation [of a federal right] must be caused by the exercise of someright or privilege created by the State or by a rule of conduct imposed by theState or by a person for whom the State is responsible. . . . Second, the partycharged with the deprivation must be a person who may fairly be said to be astate actor.The two steps converge when a claim is directed against an officer who brings the forceand weight of the state and his public office into his conduct. They diverge when thedefendant, although a formally private actor, is subject to some control or influence bygovernment and government officers. Courts often treat the constitutional and statutory requirements as identical inquiries. As a default rule, the former establishes thelatter — that is, a person who is a constitutional state actor acts u nder color of statelaw. (Lugar).§ 2.02 State Action, Action Under Color, andPublic Officials[1] The Core and Expansion of “ Under Color”Individual conduct is fairly attributable to the state when a public official, officer, oremployee — whether with full- time status, contracted to work for the government for alimited time or purpose (Filarsky v. Delia (2012)), or under contract to provide government ser v ices (West v. Atkins (1988)) — acts in accordance with state law and violates a

2 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Law17person’s constitutional rights because of constitutional defects in the law or policy followed or enforced. (Lane v. Wilson (1939)). State officials act u nder color of state law,and are subject to suit u nder § 1983, in enforcing state de jure discrimination in publiceducation or electoral pro cesses or in enforcing a municipal ordinance banning all peaceful gatherings in public spaces. A public officer also acts under color when, while notcompelled by law, he acts within the range of legally authorized discretion in enforcingstate and local law. (Hague v. CIO (1939); Bible Believers v. Wayne County (6th Cir. 2015)).The impor tant question is w hether u nder color extends to public officials acting withinthe scope of employment and in the course of performing official duties, where theirconduct v iolated federal constitutional rights but also was contrary to, inconsistentwith, or in direct violation of state law and the officers’ state- law obligations.In United States v. Classic (1941), the federal government prosecuted county electionofficials u nder § 242 for depriving African- A merican voters of the right to vote by failing to count their votes, altering ballots to show votes for dif fer ent candidates, and falselycertifying election results — all contrary to the officials’ state- law obligations to accurately count votes and properly certify the results. The officials’ conduct violated the voters’ federal constitutional rights to be f ree from race discrimination in voting, but also v iolated state election law. A 4–3 majority* held that the federal prosecution could proceed. The election officials acted u nder color of state law because “[m]isuse of power,possessed by virtue of state law and made pos si ble only b ecause the wrongdoer is clothedwith the authority of state law, is action taken ‘ under color’ of state law.” Public officialsacted under color of state law whenever their conduct deprived an individual of her constitutional rights, even when officials did so in disregard of express l egal obligations inthe course of performing their state duties.A four- Justice plurality reiterated this position four years later in Screws v. United States(1945), this time in the § 242 prosecution of a southern sheriff and his posse of deputiesfor the fatal beating of a handcuffed African- A merican arrestee outside the jail house.The Court rejected the defendants’ argument that they did not act under color becausetheir actions constituted state- law crimes or torts. The case was indistinguishable fromClassic and the princi ple that conduct could violate both state law and the federal Constitution. In both cases, government officials misused state- g ranted power. The law- enforcement officers in Screws acted within the scope of their state authority by makingan arrest, taking the victim into custody, and taking steps to make the arrest effective;they acted without that authority only because they used excessive force in effecting thatarrest. A fter reaffirming Classic’s formulation of u nder color, the Court insisted that“it is clear that under ‘color’ of law means under ‘pretense’ of law.” All acts taken in theper for mance of official duties were included, both where officers “hew to the line oftheir authority” but happened to follow or enforce unconstitutional laws and where they“overstep” that state authority to engage in unlawful conduct that also v iolated theConstitution.* Seven Justices participated in the decision in Classic in May 1941. The Court only had eightmembers during the period between the retirement of Justice McReynolds in January 1941 and theconfirmation of Justice Byrnes as his successor in July 1941. And Chief Justice Hughes did notparticipate.

182 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Law[2] M onroe v. Pape and “ Under Color” in § 1983Sixteen years later, in Monroe v. Pape (1961), the Court addressed the meaning of undercolor for purposes of § 1983 and launched modern constitutional litigation. (Nichol 1987).Thirteen Chicago police officers investigating a murder entered the home of JamesMonroe, an African- A merican man, in the m iddle of the night and without a warrant.They dragged James, his wife, and t heir children out of bed and made them stand in theliving room. Officers ransacked the house, emptying drawers and ripping mattresses.They allegedly pushed, hit, or kicked James and other family members and used racialepithets in addressing the family. James was arrested and detained for 10 hours, withoutbeing taken before a magistrate or allowed to call his attorney or f amily. He was releasedthe following day when the witness (the wife of the murder victim) was unable to identify Monroe in a line-up. Monroe then sued the City of Chicago, Chief of DetectivesPape (who led the raid on the house), and other officers. (Monroe; Gilles 2008).*As in Screws, law- enforcement officers possessed and wielded authority as law- enforcement officers, but abused that authority. They engaged in conduct that not onlywas not authorized by state law, but was contrary to, and actionable under, the state constitution, statutes, and common law. Illinois law provided civil remedies for t hose violations, and Illinois courts were open and available to provide full redress for theviolations.For the first time, an eight- Justice majority of a full Court adopted the broad construction of under color offered in Screws and Classic, incorporating it into § 1983’s civilcounterpart. Writing for the Court, Justice Douglas concluded that the phrase shouldhave the same meaning in both civil and criminal contexts, given that Congress modeled § 1983 (enacted in 1871) on § 242 (enacted in 1866 and reenacted in 1870). The setof potential defendants subject to civil suit should be at least as broad as the set of government officials subject to criminal prosecution.The Court looked to the debates over the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 to identify threemain purposes of § 1. The first aim was to “override certain kinds of state laws,” notablythe Black Codes, that expressly burdened or disabled freedmen from most incidents andrights of po liti cal and civil society. Section 1983 enabled civil lawsuits to declare invalid,and prohibit enforcement of, invidious state statutes that by their terms abridged therights or privileges of citizens.The second aim was to provide a federal remedy where state law on the books and aswritten was inadequate to protect the plaintiff’s rights.The third aim, on which Monroe focused, established the statute’s true breadth: To“provide a federal remedy where the state remedy, though adequate in theory, was notavailable in practice.” Congress in 1871 legislated against the Klan’s pervasive l egal, po liti cal, and social influence throughout the South. It was not only concerned with situations in which the Klan controlled the engines of state and local government and enactedor enforced unconstitutional laws. It also wanted to provide a remedy “against t hose representing a State in some capacity [who] were unable or unwilling to enforce a statelaw” because of the Klan’s societal influence and control. In such cases, t here was “noquarrel with the state law on the books. It was their lack of enforcement that was thenub of the difficulty.” An effective federal remedy must be available wherever state law* The victim’s wife confessed that she and her lover had conspired to commit the murder.

2 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Law19might not be enforced, wherever state rights might be denied, or wherever “prejudice,passion, neglect, intolerance, or other w ise” might produce discriminatory enforcementor non- enforcement in state court.History then fell from the majority’s analy sis. While legislating in a par tic u lar historical context in response to a par tic u lar historical prob lem, Congress wrote § 1983 ingeneral terms. The statute and its policies applied to Illinois in 1961 as much as to theKlan- dominated South in 1871, even if the same racial pathologies no longer w ere inplay or remained in play in a dif fer ent form or degree. Myriam Gilles (2008) argues thatthe latter was the case with racially discriminatory policing in Chicago of the late 1950s.Moreover, Congress designed the federal civil remedy of § 1983 to supplement statecivil remedies. Congress determined in 1871 that federal civil remedies should be available in federal court b ecause state remedies in state court might be practically unavailable or inadequate b ecause, historically, they w ere. (Mitchum v. Foster (1972)). It was notsignificant that the same conduct by the same defendants could constitute both a statetort and a deprivation of a constitutional right — that Pape and his officers committedassault, battery, trespass, and unlawful imprisonment, in addition to an unreasonablesearch and seizure in violation of the Fourth Amendment. The latter represented a dif fer ent and unique legal right deserving of dif fer ent and unique remedies in federal court.Section 1983 adopted a wholesale approach to the relationship between federal andstate remedies in light of that historical suspicion. A plaintiff need not make a retail showing of the actual inadequacy or unavailability of state remedies in her case to proceedon a § 1983 action asserting federal rights in federal court. She could proceed to federalcourt in the first instance and need show only that a person, acting under the pretenseor clothed with state authority, acted in a way that deprived her of constitutional rights. There was no preference for state law or state remedies and no requirement that statecourts be courts of first resort.Section 1983 and § 242 depart in practice on this last point. The establishment ofaction u nder color means the United States could bring a § 242 prosecution withoutregard to the actual or likely success or failure of a state prosecution and whether thesame conduct may violate both state criminal statutes and the federal Constitution. Butthe Department of Justice’s Policy on Dual and Successive Prosecutions (known as the“Pe tite Policy”) defers to state law and state courts as the primary locus of criminal prosecution and punishment where jurisdiction overlaps. A federal prosecution of conductthat violates state and federal law should be undertaken only after a deliberative pro cess, including consulting with state prosecutors to “determine the most appropriatesingle forum in which to proceed to satisfy the substantial federal and state interestsinvolved, and, if pos si ble, to resolve all criminal liability for the acts in question.” (UnitedStates Dep’t of Justice, United States Attorney Manual § 9-2.031 (Dual and SuccessiveProsecution Policy); Jacobi 2000). This reflects a retail approach, in which the federalgovernment undertakes a § 242 prosecution only upon a finding that a par tic u lar prosecution in a par tic u lar case involving par tic u lar facts is appropriate compared withstate alternatives.[3] Public- Official Defendants after MonroeMonroe, applying the Screws and Classic formulation of under color to § 1983, establishes that a defendant acts under color when he misuses state- granted power and when

202 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Lawhis misconduct is pos si ble only because he is “clothed” with state- law authority. A public official may be sued for all acts performed within the scope of his employment, whetherstate law authorizes the conduct, prohibits the conduct, or is silent as to the conduct.The analy sis focuses on whether the defendant officer wielded actual or apparentauthority from the state and w hether that authority enabled him to engage in the conduct at issue. The First Cir cuit in Martinez v. Colon (1st Cir. 1995) explained that conductmust “occur[] in the course of performing an actual or apparent duty of his office, or[when] the conduct is such that the actor could not have behaved in that way but for theauthority of his office.” This includes actions taken under the pretense of authority(Butler v. Sheriff of Palm Beach County (11th Cir. 2012)) and where the defendant performed or at least pretended to perform his official duties (Blueberry v. ComancheCounty Facilities Auth. (W.D. Okla. 2016)), even if lacking the formal authority to do whathe did, (Bonenberger v. Plymouth Twp. (3d Cir. 1997)).An official cannot misuse power that he does not possess, therefore he does not act nder color in engaging in conduct having nothing to do with t hose formal powers. Theuchallenged conduct must relate in some “meaningful way” to the defendant’s status as agovernment employee, the per for mance of his official functions, or his official powers.(Libertarian Party of Ohio v. Husted (6th Cir. 2016); Naffe v. Frey (9th Cir. 2015); Watersv. City of Morristown (6th Cir. 2001)). The acts must be part of the officer’s public dutiesor purportedly taken u nder pretense of power connected to his official position, even ifdone in a way exceeding the scope of t hose duties or that position. (Wilson v. Price(7th Cir. 2010)). The presence of personal or private motive or animus does not erase thepublic nature of the conduct, so long as the conduct was not disconnected from execution of official duties. But not every tort or other action by a government employee iscommitted under color, even conduct bearing some loose connection to the defendant’sjob functions.A public officer also may be “clothed” with state authority where he acted entirelyoutside the scope of his employment to engage in conduct that in no way could be understood as his governmental duties, but where the badges of state authority enabled theconduct. Courts frame this in terms of but- for causation — whether the defendant couldhave committed t hese acts without the aid of his state authority. Stated differently, thequestion is whether a private person could have engaged in the same conduct in the samecircumstances. (Butler). A detention officer who sexually assaulted a detainee in the jailacted u nder color; while sexual assault was in no way part of his job, he would not havehad access to or authority over the w omen he assaulted but for his position as a detention officer. (Blueberry).The complicated and recurring under- color prob lem involves off- duty law- enforcement officers. Law- enforcement officers are unique among public officials — they possess l egal authority to use physical, even deadly, force; to seize and detain p eopleor threaten to do so; and to disobey traffic and other public regulations. And they canwield those powers even when off- duty and outside of the job. The answer turns on whether the defendant suggested to observers, explic itly or implicitly, that he was actingas a law- enforcement officer within the scope of his employment, even when off- duty.The Ninth Cir cuit (Naffe) suggested:A state employee who is off duty nevertheless acts u nder color of state law when(1) the employee “purport[s] to or pretend[s] to act u nder color of law,” (2) his“pretense of acting in the per for mance of his duties . . . had the purpose andeffect of influencing the be hav ior of o thers,” and (3) the harm inflicted on

2 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Law21plaintiff “ ‘related in some meaningful way e ither to the officer’s governmentalstatus or to the per for mance of his duties.’ ”The Western District of Pennsylvania in McGuire v. City of Pittsburgh (W.D. Pa. 2016)reminded that this is a fact- specific inquiry, then offered multiple facts that purportauthority for a law- enforcement officer, includinga) “flashing a badge”; b) “identifying oneself as a police officer”; c) “wearing apolice uniform”; d) “intervening in a dispute involving o thers pursuant to a dutyimposed by police department regulations”; e) ordering the plaintiff “repeatedly to stop”; f) seeking to arrest the plaintiff; and f) using a state- issued weapon;g) “placing [the plaintiff] under arrest.”Courts also may look to the under lying circumstances that placed the off- duty officerin the situation to interact with the plaintiff and w hether t hose circumstances connectedhim to the department, to his power as a member of the department, to public ratherprivate circumstances, or to the l egal source of his power.[4] Under Color Puzzles: Public- Official DefendantsThe following events result in a § 1983 action against the officers. Consider w hether thedefendants acted under color of law under the Monroe/Screws/Classic standard. Considerthe arguments for both sides, consider the significant facts in the analy sis, and consider anyadditional facts that may be necessary for a court to resolve the issue.1. Campeau- Larion v. Kelly (Complaint, No. 09- CV-3790 (S.D.N.Y. 2009))Two New York City police officers removed Campeau- Larion from the grandstand at Yankee Stadium during a baseball game, because he left his seat during the playing of “GodBless Amer i ca” during the seventh- inning stretch, in violation of team policy.The off- duty officers worked at the Stadium pursuant to the Police Department’s “PaidDetail Program,” through which private companies and events hired uniformed police officers to provide security at vari ous venues, including ballgames. The primary purpose of theprogram was to “provide a highly vis i ble police presence” at events and venues. An incidental benefit of the program was to provide off- duty officers an opportunity to earn additionalincome. Participating officers w ere required to wear full uniform; to carry handcuffs, ser vice firearms, and a department radio; and to conform to all department grooming andappearance standards. They w ere subject at all times to department rules and regulations,including regulations regarding courtesy and contact with the public. At larger venues (suchas a baseball stadium), the officers reported to a superior NYPD officer on the scene working in the detail program in a supervisory capacity. Officers were responsible for taking all“proper police action in accordance with the circumstances” in working t hese private events.The officers also were subject to control by the hiring business or venue, in this case the NewYork Yankees Baseball Team.Campeau- Larion sues the officers who removed him from the stadium, as well as theirsuperiors and New York City, claiming that removing him from the park v iolated his FirstAmendment rights.2. Davison v. Loudoun County Board of Supervisors (E.D. Va. 2017)Davison is a citizen of Loudoun County, V irginia, active in local politics. Randall is Chairof the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, the county governing body. Randall and

222 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State LawArnett maintain the Facebook page “Chair Phyllis J. Randall.” Randall blocked Davisonfrom posting in the Comments section of the Facebook page, b ecause she did not like thecriticisms he directed towards the County School Board and its members.Randall retains full control over the page, which will not revert to the County when sheleaves office. Randall is responsible for content on the page. Arnett, Randall’s long- time friendand now her chief of staff and a County employee, has administrative access to the page,posts content, and helps to run the page. Neither Randall nor Arnett uses county- issueddevices to post or manage the page, although posts from personal devices are made duringboth work and non- work time. All posts are addressed to “Loudoun,” meaning Randall’s constituents. The page primarily includes content and photo graphs describing, advertising,and promoting Randall’s activities as Chair; Board meetings and activities; official countyproclamations and announcements; and non- Board events and c auses with which Randallis involved in her capacity as Chair.One post called on “ANY Loudoun citizen” to post in the Comments section of the page“on ANY issues, request, criticism, compliment, or just your thoughts.” Randall has engagedwith constituents in the Comments section about government m atters, such as the Countyresponse to a snowstorm and an upcoming meeting with the head of the County healthdepartment. The “About” section of the page categorizes the page as that of a “GovernmentOfficial,” and the contact information links to Randall’s County office phone, email, andwebsite. Randall’s office issues a monthly newsletter, distributed via a county mailing listand posted on the county web page; a link at the bottom of the newsletter brings readers tothe Chair Phyllis J. Randall Facebook page. Randall also posts about personal, non- Chairrelated matters on the page, such as photos of a recent shopping trip or a discussion of herlove for German. In addition, Randall maintains a second Facebook page, “Friends of Phyllis Randall,” with a profile describing her family and personal life; Arnett does not haveadministrative access to that page.Davison brings a § 1983 action against Randall, claiming that blocking him from the Comments section v iolated the First Amendment and F ourteenth Amendment due pro cess.3. Wilson v. Price (7th Cir. 2010)Price is a city alderman who received numerous complaints from constituents about carsillegally parked in front of an auto- repair shop in his district. When the city failed to act onhis requests to move the cars, Price went to the shop, where he found Wilson, a mechanicemployed t here. When Wilson refused to move the cars or to call the shop owner, Pricepunched Wilson in the head several times, leaving him unconscious and with a fracturedjaw.Wilson files a § 1983 action, alleging that Price used excessive force in violation of theFourth Amendment.4. Naffe v. Frey (9th Cir. 2015)Frey is a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles County assigned to the gang unit; healso is a conservative po liti cal activist and blogger, commenting on his blog and Twitter aboutconservative politics, liberal media bias, and criminal law. He often references his positionand experiences as a prosecutor. His blog and Twitter page both display a disclaimer: “Thestatements made on this web site reflect the personal opinions of the author. They are notmade in any official capacity, and do not represent the opinions of the author’s employer.”One topic of Frey’s blogging was Naffe, another conservative po liti cal activist who had afalling out with a friend of Frey’s (also a conservative activist). Frey wrote eight unfavorable

2 · State Action and “ Under Color” of State Law23blog posts about Naffe and tweeted dozens of threatening and harassing statements abouther. One of his tweets stated that he wanted to identify the California criminal statutes Naffehad admitted violating. Fi nally, Frey posted more than 200 pages of deposition transcriptsfrom a lawsuit between Naffe and Naffe’s former employer that contained personal information, such as her address and social security number.Naffe files a civil action against Frey containing one § 1983 claim, for a violation of herFirst Amendment right to petition government for redress of grievances (arising from Freypublishing the materials from her lawsuit).5. Butler v. West Palm Beach Sheriff (11th Cir. 2012)Collier is a corrections officer at a boot- camp fa cil i ty for minors run by the County Sheriff ’s Office.Collier returned home from work one day to find Butler, a teen- age boy, hiding in herd aughter’s closet, both teen agers naked a fter having had sex. Collier was wearing her uniform and had her gun belt with ser v ice pistol. Collier yelled at Butler and punched him,trained her gun on him and threatened to shoot him if he did not follow her commands; shethen handcuffed him and made him stay on his knees for a “prolonged period,” threatening toshoot or kill him if he did not obey her. At one point, still holding Butler at gunpoint, Colliercalled her supervisor at the County Sheriff ’s Office to ask what charges she might bringagainst Butler. Butler fi nally was allowed to get dressed and leave, although Collier pointedthe gun at him as he was dressing. Collier also warned Butler not to file charges or report theincident.Butler brings a § 1983 action against Collier, alleging she used excessive and unreasonable force in violation of the Fourth Amendment.[5] State Actors and State ActionCourts treat the Fourteenth Amendment requirement of action by a state and the§ 1983 requirement of a person acting under color of state law as identical. As a default,a person acting as

A 4–3 majority* held that the federal prosecution could pro-ceed. The election officials acted under color of state law because “[m]isuse of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made pos sible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law, is action taken ‘ under color’ of state law.” Public officials

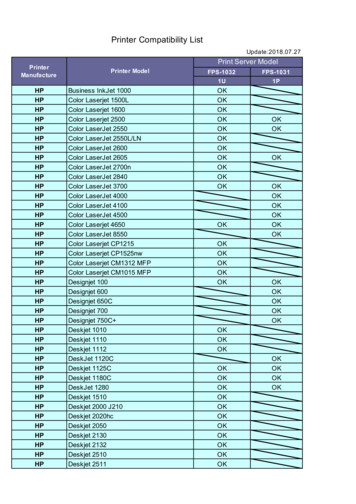

FPS-1032 FPS-1031 1U 1P HP Business InkJet 1000 OK HP Color Laserjet 1500L OK HP Color Laserjet 1600 OK HP Color Laserjet 2500 OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2550 OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2550L/LN OK HP Color LaserJet 2600 OK HP Color LaserJet 2605 OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2700n OK HP Color LaserJet 2840 OK HP Color LaserJet 3700 OK OK HP Color LaserJet 4000 OK HP Color LaserJet 4100 OK

o next to each other on the color wheel o opposite of each other on the color wheel o one color apart on the color wheel o two colors apart on the color wheel Question 25 This is: o Complimentary color scheme o Monochromatic color scheme o Analogous color scheme o Triadic color scheme Question 26 This is: o Triadic color scheme (split 1)

TL-PS110U TL-WPS510U TL-PS110P 1 USB WiFi 1 Parallel HP Business InkJet 1000 OK OK HP Color Laserjet 1500L OK OK HP Color Laserjet 1600 OK OK HP Color Laserjet 2500 OK OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2550 OK OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2550L/LN OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2600 OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2605 OK OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2700n OK OK HP Color LaserJet 2840 OK OK HP Color LaserJet 3700 OK OK OK

79,2 79,7 75,6 86,0 90,5 91,1 84,1 91,4 C9 C10 C11 C12 C13 C14 C15 88,5 87,1 84,8 85,2 86,4 80,5 80,8 Color parameters Color temperature Color rendering index Red component Color fidelity Color gamut Color quality scale Color coordinate cie 1931 Color coordinate cie 1931 Color coordinate Color coordinate

With the Toshiba e-STUDIO2330c/2830c multifunction color systems, you get high-speed, high-quality halftones and uncompromising color quality. Beautiful color. Accurate color. Color that means business. Toshiba color is color without compromise, thanks to innovations such as our patented e-Fine processors, microfine toner, and new developer.

2ND ACCENT COLOR: Appalachian Brown 2115-10 2. MAIN COLOR: Coral Essence 2007-40 1ST ACCENT COLOR: Old Navy 2063-10 2ND ACCENT COLOR: Fountain Spout 2059-70 3. MAIN COLOR: Louisburg Green HC-113 1ST ACCENT COLOR: Lancaster Whitewash HC-174 2ND ACCENT COLOR: Tangy Orange 2014-30 4. MAIN COLOR: Blue Angel

INTERACTION OF COLOR: An Abridged Version of the Josef Albers Color Course Dick Nelson, Teacher Course Description: "The aim of such a study is to develop--through experience--by trial and error--an eye for color. This means, specifically, seeing color action as well as feeling color relatedness." Albers Assignment #1: One Color Appears as Two.File Size: 1MB

DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY Telangana University Dichpally, Nizamabad -503322 (A State University Established under the Act No. 28 of 2006, A.P. Recognized by UGC under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC Act 1956)