NEW YORK Volume VII No. 1 Fall/Winter 2003 TRANSPORTATION .

NEW YORKVolume VII No. 1 Fall/Winter enterLetter from the EditorThe leaves are falling, the weather iscooling and once again all roads andtransit routes led to Yankee Stadium(though it did not end as we may haveliked). Another tradition that continuesis the lack of an agreement on theFederal budget for transportation. Thefinancing dilemma is exacerbatedthis year by the lack of long-termreauthorizations of the highway, transit and airport funding programs. Thetemporary extension of the Federalfunding programs will limit commitments to mega-projects such as theEast Side Access Project and the SecondAvenue Subway.The lack of accord on the new authorization also means the continueddefense of transportation funding forNew York, New Jersey and the otherNortheastern States from the Southern(Continued on page 7)Inside NYTJA Healthy Investment inTransportationBy Congressman JerroldNadlerMore Than A TrainBy F. Carlisle ToweryUp Close with Mary E.Peters, Federal HighwayAdministratorBy Janette Sadik-KhanThe Central LondonCongestion Charge: AnUpdate So FarBy Jay WalderA Breakfast with KevinCorbettBy Adrienne Lombardo4th Annual Tri-State TransitSymposium SummaryBy Allison L. C. de CerreñoO VERCOMING THE C HALLENGESI MPLEMENTING A IRT RAIN JFKOFBY ANTHONY G. CRACCHIOLODespite the tragic events of September 11,2001, and the recent blackout of August 14,2003, New York City has demonstrated — twiceagain — that it is a class act worthy of thedesignation “international capital” of theworld. A destination point each year formillions of tourists and travelers from all overthe globe, the City’s primary internationalgateway is John F. Kennedy InternationalAirport (JFK) — approximately 16 miles outside of Manhattan.Primary access to JFK is via the heavily trafficked Van Wyck Expressway (VWE), which isused by 75 percent of JFK air passengers —because it is the only north-south Queenshighway that allows commercial traffic andconnects with the Long Island Expressway(I-495) and I-95 — and is also the main routefor airport employees and air cargo/servicevehicles. On airport, the heavy presenceof buses, taxis, limousines and privatelyowned vehicles in the Central Terminal Area(CTA) creates congested terminal frontagesand poses logistical problems to efficienttraffic management.To alleviate these problems, The PortAuthority of New York and New Jersey(PANYNJ) will put into service by the end of2003, a 1.9 billion light rail airport accesssystem that will relieve congestion on theVWE and improve intra-airport mobility. Thenew rail transportation system — calledAirTrain JFK — is the first fully automatedrail transit system in New York City, and isexpected to carry an estimated 12.4 millionpassengers a year. Operating both as a rapidtransit (airport access) system and an onairport people mover, the 8-mile AirTrainJFK will connect JFK passenger terminalswith each other, with the long term parkinglot, with car rental facilities and, most sig-Courtesy of the Port Authority of New York & New Jerseynificantly, with the MTA Long Island Rail Road(LIRR) and New York City Transit (NYCT)s t a tions at Jamaica and the NYCT stationat Howard Beach. By reducing automobiletrips and cutting transit travel time betweenJFK terminals and midtown Manhattan tol e s s than an hour, and creating a new hubat Jamaica, AirTrain JFK — a safe, reliableand environmentally sound transportationalternative — will allow the airport to continue its growth and support New York Citybusinesses and the City’s 15 billion-a-yeartourism industry.The Challenges of Building AirTrain JFKAirTrain JFK is the culmination of more than 30years of efforts to build and implement aneffective airport access system in New York.The development of AirTrain JFK has been along and arduous journey, with many challenges along the way: from funding issues, along regulatory process, opposition from various groups, coordination with the city andstate transportation departments, coordinationand agreements with the MTA and their operating agencies (LIRR and NYCT), to the actual(Continued on page 2)1

2NEWYORK TRANSPORTATION JOURNALA I RT R A I NC O N T.(Continued from page 1)construction of the system.FundingDesigned to take advantage of and complementNew York’s extensive regional rail transportationnetwork (including compatibility with NYCT andLIRR systems to leave open the possibility of afuture “one-seat” ride between Manhattan andJFK), the AirTrain JFK project received its FinalEnvironmental Impact Statement Record ofDecision in July 1997 and FAA approval for partialfunding in 1998 under the 1990 Aviation Safetyand Capacity Expansion Act (an amendment ofthe Federal Aviation Act of 1958), which authorized the creation of a program that would allowairport operators to collect a fee of up to 3, thePassenger Facility Charge (PFC), from enplaningpassengers to fund eligible airport improvementprojects. Seventy percent of AirTrain JFK fundingcomes from PFCs, the balance from PortAuthority capital funds.Overcoming OppositionWhen environmental and initial funding approvalwas received from the Federal AviationAdministration (FAA) for AirTrain, there remainedother hurdles to overcome — not the least ofwhich was opposition to the project from theairlines, transportation advocacy groups, andother special interest and community groups.Some critics insisted on a “one-seat ride” fromManhattan to JFK, while others suggested alternative routes. The airline industry, representedby the Air Transport Association (ATA), acknowledged that improved airport access was needed,but opposed the use of PFC funds to do so, main-New York Transportation JournalElliot G. Sander, PublisherAllison L. C. de Cerreño, EditorEditorial BoardJohn FalcocchioJosé Holguín-VerasRobert PaaswellHenry PeyrebruneGene RussianoffDesign and LayoutIsabella PiersonJanette Sadik-KhanBruce SchallerSam SchwartzRoy SparrowRobert Yarotaining that improved access is the responsibility of state and local government.Once the FAA approved the PA’s PFC application two lawsuits were initiatedchallenging the approval; in both cases, two Federal Appeals Courts ruled infavor of the FAA’s PFC funding approval and the project proceeded.New York City required the project to undergo the Uniform Land Use ReviewProcess (ULURP) in order to transfer City property interests necessary primarilyfor the Jamaica segment of the project. This process involved extensive community input and action by the Queens Borough Board, City Planning Commissionand New York City Council.Construction ChallengesThe biggest challenge, by far, of improving access to JFK was the herculean task of physically building the system without severely impacting airportoperations and peak period traffic on the VWE. Constructing both the on-airportand off-airport components necessitated an extensive outreach effort and coordination with diverse interests, including the airlines and airport operationspersonnel, the region’s transportation agencies, the traveling public, andthe surrounding communities.Maintaining Airport OperationsThe PA awarded a design/build/operate/maintain (DBOM) contract to the AirRail Transit Consortium (ARTC) that enabled both parties to advance early construction while design was still underway. This strategy allowed both the PA andthe contractor to fast-track construction while permitting the team to respondquickly to unforeseen field conditions, changing airport and highway operationalrequirements and community concerns; it also allowed for the avoidance ofpotential contract claims. To minimize the impact on airport operations, the PAand its consultants designed the one-quarter mile long tunnel under two airporttaxiways, and relocated the on-airport North Service Road along the on-airportVWE to create the right-of-way for AirTrain’s at-grade section. Project staff alsoworked closely with the airlines to construct the AirTrain stations at their terminals without reducing their ability to service air passengers. Also, uniquedesign characteristics were incorporated in the Central Terminal Area stationsto meet the special needs of each airline terminal and to maximize serviceoptions to airline passengers. For example, the AirTrain station at Terminal 4The New York Transportation Journal is published by the NYU Wagner Rudin Center forTransportation Policy & Management in conjunction with the Rudin Center’s Adivsory board,the Council on Transportation.The Rudin Center gratefully acknowledges the foundation, corporate, and individual sponsorsthat make possible our efforts to promote progressive transportation policy, including theNew York Transportation Journal.The views expressed in the New York Transportation Journal are those of the authors andnot necessarily those of New York University, the Rudin Center, or any of its affiliated organizations and funders.Letters to the Editor and other inquiries may be addressed to Allison C. de Cerreño at:Rudin Center for Transportation Policy & ManagementNYU Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service4 Washington Square NorthNew York, NY 10003phone: (212) 998-7545; fax: (212) 995-3890Email: rudin.center@nyu.eduwww.nyu.edu/wagner/rudincenter

VOLUME VII NO.(the new International Air Terminal) islocated within the building, allowing directaccess to both arrival and departure areas,while Terminal 7’s (British Airways) AirTrainstation is integrated with a new parkinggarage.Guideway Construction and TrafficCoordinationDue to its proximity to the active roadwayand residences along the service roads, construction of the three-mile stretch of theelevated guideway in the eleven-foot median of the VWE between Jamaica Station(Atlantic Avenue) and the airport was probably the most challenging. In addition to thepermanent easement granted by the NewYork State Department of Transportation(NYSDOT) for use of state property along theVWE and over the Nassau Expressway andBelt Parkway, close coordination wasrequired with NYSDOT and the New York CityDepartment of Transportation (NYCDOT) for“AirTrain JFK is the culmination of more than 30years of efforts to buildand implement aneffective airport accesssystem in New York.”both AirTrain guideway construction andtraffic management. The VWE’s outsideshoulders and on and off ramps werewidened and the shoulders temporarilyconverted to travel lanes in order to maintain three traffic lanes in each direction during peak travel periods; at other timesa minimum of two traffic lanes in eachdirection were provided to permit construction of the guideway.When it was announced that VWE guidewayconstruction would necessitate the temporary closing of travel lanes on area highways,motorists were convinced that traffic wouldbe backed up for many miles beyond theproject area. To minimize adverse trafficimpacts, the project team developed andimplemented a comprehensive Maintenanceand Traffic Protection Plan together with apublic information program. An around-theclock traffic study was conducted along theVWE from South Conduit to Hillside Avenues,and at critical intersections during peak1 FALL/WINTER 2003hours. Study results allowed traffic engineers to determine the best times to schedule construction with the least impact tomotorists and area property owners. Thesequence of construction had previouslybeen coordinated with NYSDOT and NYCDOT,and the AirTrain project team worked in tandem with NYSDOT to complete an additional 34 million of NYSDOT funded infrastructureimprovements along the corridor, includingtwo bridge replacements at 109th and FochBoulevard, improved on and off ramps withimproved acceleration and decelerationlanes, and widened highway shoulders.AIRTRAIN FACTS & FIGURESFleetThe AirTrain fleet includes 32vehicles, 60' long by 10' wide,able to travel at a maximumspeed of 60 mph. The fleetvehicles are characterized by:Configuration for bi-directionaloperation;Capacity for single unit useor in multiples of up tofour-car trains;Modern, streamlined exteriorswith wide doors for luggagecarrying passengers;A VWE traffic control desk, located atNYSDOT’s Joint Traffic Operations Center inLong Island City, was then set up to monitorconstruction and traffic flow using roadsidecameras, Shadow Traffic and variable message signs. Traffic enforcement agents,Highway 3 Police and three on-site towtrucks were also dedicated to the effort. Ageneral 800 number was installed, and anAirTrain Web site was created to provideproject and construction information. Whenthe time came to temporarily close theNassau Expressway, Belt Parkway and Northand South Conduit Avenues, a media blitzblanketed the area for days leading up toand during the closures and motorists wereadvised to use alternate routes. With thesupport and cooperation of NYCDOT andNYSDOT the closures ran smoothly and thecontractor was able to complete construction of the approximate three miles of elevated guideway ahead of schedule, in arecord 22 months.Interiors with seating, luggageracks, and open floor space forluggage carts;Full ADA-compliance with extraenhancements.Guideway:Single-track elevated6 mi.Double-track elevated3.2 mi.Command and Control:Fully automated, driverlessoperation controlled by movingblock train control system;Automated storage yardcomplementing mainlineoperations.Peak Period Headway:Intermodal Terminal ConstructionThe AirTrain intermodal terminals at HowardBeach and Jamaica also required major construction adjacent to and over NYCT andLIRR tracks and platforms entailing closecoordination with rail operations. The project included replacement of NYCT’s HowardBeach Station subway mezzanine, completerehabilitation of the NYCT platforms andcanopies by the PA on behalf of NYCT. Theproject also included building a new LIRRJamaica Station mezzanine, a portal roofover the five LIRR platforms and eleventracks, and completely rebuilding the 1913vintage platforms and canopies for the LIRRwhile allowing almost 700 trains a day tocontinue operating without delays. Closecoordination and full support from NYCT andLIRR were essential to achieving successfulconstruction results to date.Central Terminal Area2 min.From Howard Beachor Jamaica4 min.Travel Times:Complete triparound CTA8 min.Midtown Manhattanto JFK on LIRR45 min.Downtown Manhattanto JFK onNYCT subway60 min.Fare:Single trip 5Monthly pass(unlimited trips) 40CTA circulator,to long-term parkingand car rental agenciesfree(Continued on page 14)NEWYORK TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL3

4INNEWYORK TRANSPORTATION JOURNALTHER EGIONA H EALTHY I NVESTMENTINT RANSPORTATIONB Y C ONGRESSMAN J ERROLD N ADLEROne of the main tasks before the U.S. Congress this year is toreauthorize the six-year transportation funding bill, known asthe Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21).Quality transportation infrastructure is an essential componentof our everyday lives. In addition to being critical to ournational security, transportation improvements will bringnumerous economic and environmental benefits across thenation. Efficient roads and rails improve the flow of goods,lower the cost of doing business, make the economy more productive, and reduce pollution.According to Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) data,each 1 billion spent on transportation creates 47,500 jobs and 6.1 billion in economic activity. In today’s economy, such aninvestment is not only wise, but imperative. As the seniorDemocrat from New York on the House Transportation &Infrastructure Committee, one of my top priorities is to ensurethat TEA-21’s successor has enough funding to address adequately the United States’ surface transportation needs.The Transportation & Infrastructure Committee recently proposed at least 50 billion annually over the next six years forTEA-21 reauthorization. Unfortunately, the House passed a resolution authorizing only 39 billion a year, barely sufficient tomaintain the status quo. We must do more than simply maintain our existing system. One of Congress’ primary goals inTEA-21 reauthorization must be to expand and improve ourtransportation assets to reduce congestion, improve the flowof goods and people, and spur economic growth.Rather than authorize sufficient transportation funds, some inCongress would prefer to fund some states adequately by shifting funds from other states. At least 17 states would losetransportation funds; New York alone would lose 300 millionevery year. To combat this, the Fair Alliance for IntermodalReinvestment, of which I am a member, is working to ensure“Building new roads alone cannotalleviate congestion. We must alsofind ways to divert freight from trucksto rail.”“Lawmakers have some tough choicesto make.one of the most importantinvestments we can make is in ourinfrastructure.”that the formula that allocates federal highway dollars to thestates is protected.The so-called SHARE Coalition, which advocates changing thecurrent formula, argues that states like New York get too muchback in transportation funds compared to what they contributein gas taxes to the highway and transit trust fund. This is a verynarrow view that misses the bigger picture. For example, NewYorkers rely heavily on mass transit, and therefore, contributeless in gas taxes than more gas-guzzling states. States like NewYork should be rewarded, not punished, for investing in masstransit and becoming more energy efficient. Congress shouldfocus on ways to increase infrastructure investments to createjobs and spur economic growth, not on punishing energy-efficient states by taking scarce resources away from them.Building new roads alone cannot alleviate congestion. We mustalso find ways to divert freight from trucks to rail. It is estimated that the volume of freight — therefore of truck traffic —entering the New York metropolitan region will increase by 79percent in the next 20 years. Our already congested highwaynetwork (which cannot be substantially expanded) simply cannotbe expected to handle a traffic increase of this magnitude. If notdealt with, our inability to accommodate the expected jump infreight volume will put a lid on economic growth in the region —to say nothing of the delays to be expected on the roadways.Exacerbating this problem is the fact that New York is the onlymajor port city in the United States that has never built a railfreight connection across its harbor or river. Until such a connection is made, increased traffic on the I-95 corridor will continue to bottleneck in northern New Jersey and New York City. Toprovide the existing rail-freight system east of the Hudson Riverin New York with a major link to the rest of the continent, wemust construct a rail freight tunnel under New York Harbor.Fortunately, the Cross-Harbor Tunnel project is well under way.Congress appropriated funds to the New York City EconomicDevelopment Corporation for a Major Investment Study, whichwas completed in 2000, and for an Environmental Impact

VOLUME VII NO.1 FALL/WINTER 2003FREIGHT FACTSFreight Flows in the RegionTrips with.No origin or destinationin the region11%Either origin or destinationin the region74%Both origin and destinationin the region15%Freight Moved by Railin NY Metropolitan RegionEast of HudsonStatement, which is expected to be releasedin September. These studies have confirmedthat such a tunnel will be extremely successful in all respects, including providing anample return on any public investment.The Cross-Harbor Tunnel has a benefit-tocost ratio of 2.2 to 1 — the highest of anymajor transportation project currentlyunder consideration in New York. Moreimportantly, the tunnel would remove atleast 1 million tractor-trailer trucks per yearfrom the roads in northern New Jersey andNew York City. This means reduced congestion for passenger transports, cleaner air,lower-cost consumer goods, and a generallyreduced cost of doing business for the area’smore than 20 million people. It does nottake much of an imagination to see the benefits of removing a million trucks from

A Healthy Investment in Transportation By Congressman Jerrold Nadler More Than A Train . ments to mega-projects such as the East Side Access Project and the Second Avenue Subway. . and South Conduit Avenues, a media blitz blanketed the area for days leading up to

New York Buffalo 14210 New York Buffalo 14211 New York Buffalo 14212 New York Buffalo 14215 New York Buffalo 14217 New York Buffalo 14218 New York Buffalo 14222 New York Buffalo 14227 New York Burlington Flats 13315 New York Calcium 13616 New York Canajoharie 13317 New York Canaseraga 14822 New York Candor 13743 New York Cape Vincent 13618 New York Carthage 13619 New York Castleton 12033 New .

N Earth Science Reference Tables — 2001 Edition 3 Generalized Bedrock Geology of New York State modified from GEOLOGICAL SURVEY NEW YORK STATE MUSEUM 1989 N i a g a r R i v e r GEOLOGICAL PERIODS AND ERAS IN NEW YORK CRETACEOUS, TERTIARY, PLEISTOCENE (Epoch) weakly consolidated to unconsolidated gravels, sands, and clays File Size: 960KBPage Count: 15Explore furtherEarth Science Reference Tables (ESRT) New York State .www.nysmigrant.orgNew York State Science Reference Tables (Refrence Tables)newyorkscienceteacher.comEarth Science - New York Regents January 2006 Exam .www.syvum.comEarth Science - New York Regents January 2006 Exam .www.syvum.comEarth Science Textbook Chapter PDFs - Boiling Springs High .smsdhs.ss13.sharpschool.comRecommended to you b

Find the volume of each cone. Round the answer to nearest tenth. ( use 3.14 ) M 10) A conical ask has a diameter of 20 feet and a height of 18 feet. Find the volume of air it can occupy. Volume 1) Volume 2) Volume 3) Volume 4) Volume 5) Volume 6) Volume 7) Volume 8) Volume 9) Volume 44 in 51 in 24 ft 43 ft 40 ft 37 ft 27 .

CITY OF NEW YORK, BRONX, KINGS, NEW YORK, QUEENS, AND RICHMOND COUNTIES, NEW YORK 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of Study This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) revises and updates a previous FIS/Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) for the City of New York, which incorporates all of Bronx, Kings, New York, Queens, and Richmond counties, New York, this alsoFile Size: 1MB

Garden Lofts Hoboken,New York Soho Mews 311 West Broadway, New York 8 Union Square South, New York 129 Lafayette St., New York The Orion Building 350 West 42nd St., New York Altair 20 15 West 20th St., New York Altair 18 32 West 18th St., New York The Barbizon 63rd St. & Lexington Ave., New York T

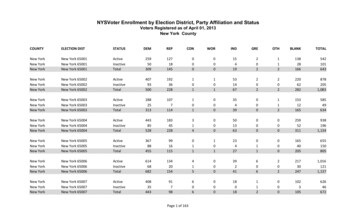

New York 65024 : Active . 648 : 108 . 0 : 4 . 19 : 1 . 0 : 324 . 1,104 New York New York 65024 Inactive 27 8 0 0 0 0 0 12 47 New York New York 65024 Total 675 116 0 4 19 1 0 336 1,151 New York : New York 65025 . Active

relation to persons joining the New York state and local retirement system, the New York state teachers’ retirement system, the New York city employees’ retirement system, the New York city teachers’ retirement system, the New York city board of education retirement system, the New York city police pension fund, or the New York

18/10 Stainless Steel New York-00 5 pc. placesetting (marked u) New York-01 Dinner Knife u 24 cm New York-02 Dinner Fork u 20.5 cm New York-03 Salad Fork u 18.8 cm New York-04 Soup Spoon (oval bowl) u 18.8 cm New York-05 Teaspoon u 15.5 cm New York-06 Cream Soup Spoon (round bowl) 17.5 cm New York-07 Demitasse Spoon 11 cm